The election is on everyone’s mind as SCR presents ‘All the Way’ and ‘District Merchants’

- Share via

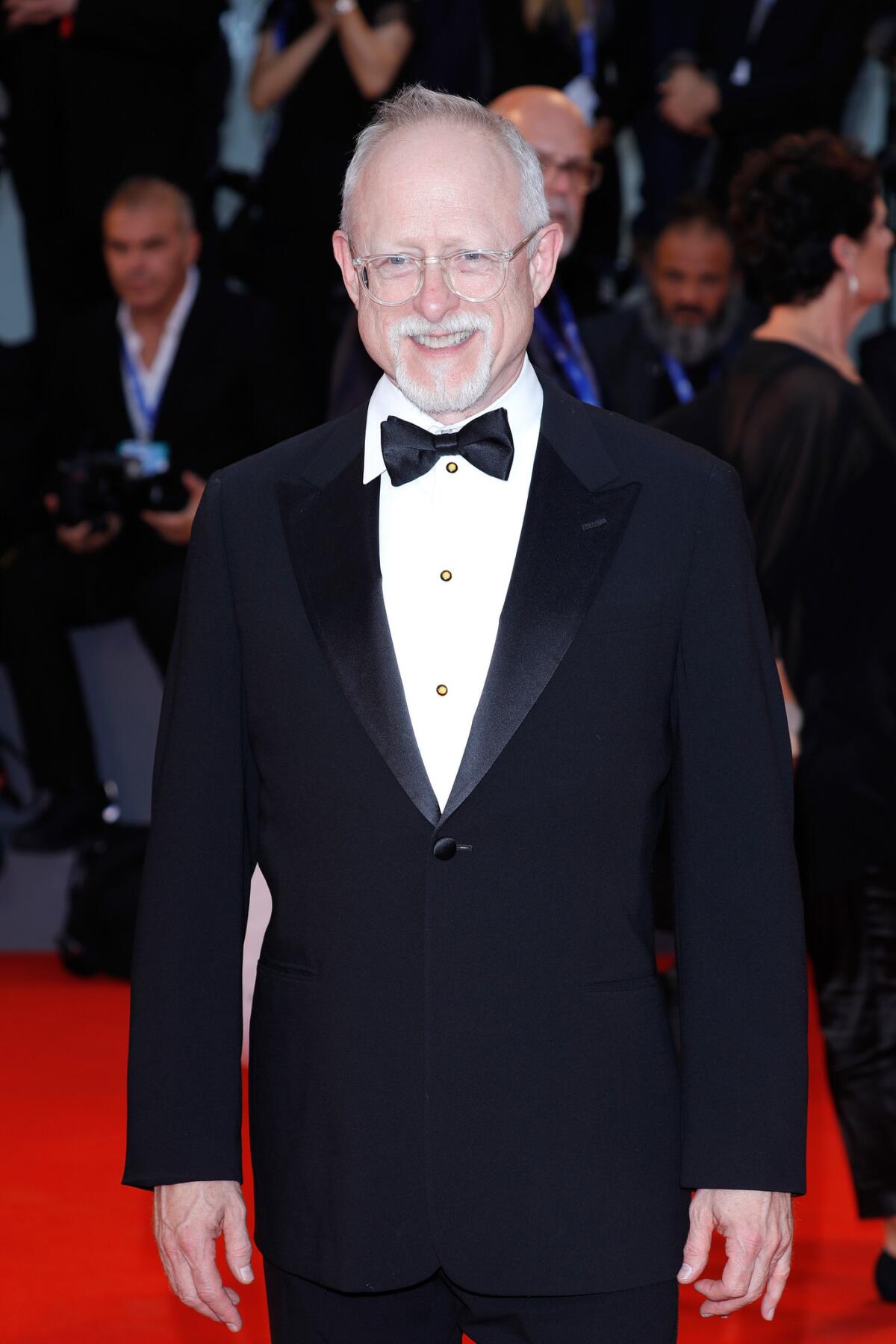

History is more complicated than the simple version we’re told in school or around the dinner table, says South Coast Repertory’s artistic director, Marc Masterson.

He is talking about Lyndon Baines Johnson in “All the Way,” the Costa Mesa theater’s main-stage season-opener, but the observation also fits the polarizing fictional figure in the play he chose for SCR’s second stage. In “District Merchants,” the Shylock of Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice” is re-imagined as a businessman and moneylender in Reconstruction-era Washington, D.C.

Both plays capture America’s struggle to follow its better impulses against the headwinds of prejudice, partisanship and self-interest.

Robert Schenkkan’s “All the Way” — the HBO version of which enters Sunday’s Emmys with nominations for outstanding television movie and for star Bryan Cranston, among other nods — covers 12 breathless months in 1963-64 as the complex and often contradictory Johnson ascends to the presidency, maneuvers a Civil Rights Act through Congress (succeeding where his slain predecessor, John F. Kennedy, had been stymied) and wins a sharp-elbowed reelection campaign. Through it all, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. spurs him on as both adversary and like-minded crusader. Resistance to change emerges in any number of grisly forms, including the slayings of three young civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Miss.

“District Merchants” by Aaron Posner, the red-hot playwright of “Stupid … Bird,” relocates “Venice” to a post-Civil War D.C. where the roadblocks to change are likewise daunting. There a Jewish businessman, treated as an outsider, operates alongside an African American one who is similarly marginalized. Their wary coexistence is refracted in the characters around them, all of whom are barred, in one way or another, from full inclusion in the American dream. Posner labels the tale “an uneasy comedy.”

Performed during the run-up to the election, each play gains resonance. Lines leap out as though you’d heard them on the news moments before.

“This is about those who got more, wantin’ to hang on to what they got, at the expense of those who got nothin’.” — Lyndon Baines Johnson in “All the Way”

“Talk about someone being Shakespearean,” Schenkkan says. “Johnson was not just big in size, but big in his ambitions and his faults — just a startling figure straying across the American political landscape.

“In many ways ... we live in the world that Lyndon Johnson created.”

Schenkkan, winner of the 1992 Pulitzer drama prize for “The Kentucky Cycle,” set out to write the equivalent of one of Shakespeare’s history plays, simultaneously revisiting the past and pondering the present.

The LBJ of “All the Way,” which won the 2014 Tony for best play, is plainspoken, occasionally profane and often funny. A U.S. representative, then senator for Texas for 24 years before becoming Kennedy’s vice president, he knows how Washington works, and throughout the play we see him chameleonically shift his tone and tactics to extract what he needs.

To make his LBJ sound like the real thing, Schenkkan scoured biographies and studied tapes Johnson made (often surreptitiously) of his conversations. Some of the lines are genuine LBJ, but “the bulk of the language here is mine,” the playwright says, his native Texas twang musicalizing the conversation.

Johnson, a do-what-it-takes-to-win type, inspired mixed feelings in Texans, but as he ascends to the presidency in “All the Way,” he proves to be a forceful, inclusive leader who presses for civil rights legislation and launches a war on poverty, the latter of which will establish such programs as Medicare.

While King and his colleagues work to activate every sympathetic citizen, LBJ turns the full force of his personality to civil rights, bombarding lawmakers with carrots and sticks. His “those who got more” line is both carrot and stick. “That’s my line, one I quite like,” Schenkkan says, “and it’s a line very much inspired by my own sense of where we are today. To me it really is a kind of indictment of the established interests who are so opposed to really dealing with racial and financial inequality in the country today.”

By the end of Act 1, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 has been passed, but at a cost.

“I tend to think of that election, 1964, and the year that this [play] covers, November 1963 to November 1964, as kind of the origin story for where we are today,” Schenkkan says. It “completely alters the political landscape. The South, which has been solidly Democratic since Reconstruction, will shift as a result of Lyndon Johnson’s support of and passage of the ’64 and ’65 civil rights bills and become Republican.”

As emotions run high in “All the Way,” the already violent South erupts with the fresh carnage of the slain trio of volunteers working on behalf of the Congress of Racial Equality, prompting the distraught leader of that group, David Dennis, to declare: “I’m sick and tired of going to funerals for black men who have been murdered by white men.”

“That sentence” — a direct quote of history — “resonates so strongly today,” Schenkkan says. “In every performance, that’s a moment you can feel the audience shudder.”

The civil rights struggle continues today, the playwright says. The nation has its first African American president, but Schenkkan regards the congressional obstruction that President Obama has faced as evidence of institutional racism. The country continues to avoid “long-overdue conversations about race and equality,” Schenkkan says, which is making the current election “disoriented and painful.”

“We have a long, complicated history of conflict when it comes to race,” says Masterson, who directed SCR’s production. “It is part of the American story, and I don't think the theater is going to solve it, but I think it's an opportunity for us to look at our culture and perhaps understand things in a different way.”

“This country is built to drive us all insane. Or people like me, anyway.” — Benjamin Bassanio, an African American businessman in “District Merchants”

“District Merchants,” like “All the Way,” is Shakespearean in its use of the past to mirror today. And, of course, it’s Shakespearean in more obvious ways.

It isn’t exactly an adaptation of “The Merchant of Venice.” “It is more like a variation on a theme or a series of theatrical what-ifs,” Posner says. He repeats about six lines of actual Shakespeare and pretty much follows the original story map, but he has thoroughly re-imagined the characters and their motivations.

Posner, who is also an in-demand director, established his writing cred as an adapter of such works as Chaim Potok’s “My Name Is Asher Lev,” but he’s become one of the country’s most-produced playwrights with his more free-form reworkings of Chekhov, “Stupid … Bird” (i.e., “The Seagull”) and “Life Sucks” (“Uncle Vanya”), as well as this highly praised Shakespearean riff, given its premiere at Washington, D.C.’s Folger Theatre in June.

The big event of the play, which opens Oct. 7, is the loan that one man makes to another and what happens when the unusual collateral — a pound of flesh — comes due. But as in the original, which is categorized as one of Shakespeare’s comedies, the men and their standoff mostly provide context for the romances blooming among their children or associates.

The black merchant Antoine DuPre (the Antonio of Shakespeare's play) takes out the fateful loan to bankroll his friend Benjamin Bassanio in courting wealthy Portia. Benjamin is a light-skinned African American whom Portia assumes is white. Jessica, the daughter of Jewish moneylender Shylock, is meanwhile wooed by an acquaintance of Antoine and Benjamin's (Shakespeare's Lorenzo), who here is Finnegan Randall, an Irish vegetable hawker.

There’s a lot of flirtation going on, but this is a romantic comedy Shakespeare-style, so there are serious matters for the audience to consider as well.

After the Emancipation Proclamation, the utter subjugation of slavery morphed into more covert forms, Posner says. “You only have to look at these new voter ID laws to see that there are still people being denied.”

To show how pervasive this “systematic shutting out of power” has been, he populates his story with a range of ethnicities.

In 1870s America, “whiteness was defined by more than white skin,” Posner, who is Jewish, points out. “Jews were not white. … The Irish were not white.”

Michael Michetti, who directed “Stupid … Bird” at the Theatre @ Boston Court in Pasadena two years ago and is directing “District Merchants” for SCR, admires the way this not only sets up one of the play’s main themes but also recontextualizes one of the original play’s biggest problems.

Shakespeare’s depiction of Shylock might have seemed uncommonly sympathetic in the 1590s, but today it comes across as baldly anti-Semitic. “District Merchants,” however, puts everyone in Shylock’s situation, making it easier to read his brusqueness and hoarding as reactions to isolation — to being shut out of the mainstream. “Every character is in some way disenfranchised,” Michetti says, “through skin color, through their religious beliefs, through their gender, through their socioeconomic or immigrant status. … Everyone is dealing with some kind of prejudice.”

They stumble before they find their way.

“If you’re being discriminated against by ‘the man,’ surely there should be an easy alliance among those who are discriminated against,” Posner says, “but, of course, that’s not the history of America.”

Instead of unity, people often see divisions — a tendency that Posner observes in the run-up to November’s elections. “The political use of scapegoating, or having somebody to blame for our problems, whether that was the Irish in the 1870s, or the Italians or the Jews or the blacks, or now the Muslims or the immigrants, there’s always somebody who can be pointed to to be a problem.”

But Posner nudges his characters on track. In one of the play's key speeches, Antoine recalls his mother teaching him to look beyond people's surfaces “to see what was really going on." And Shakespeare’s “quality of mercy” speech becomes an appeal to follow the golden rule.

Posner sees the 1870s of his play as well as the 1960s of “All the Way” as key moments when Americans asked, “Can we come together? Can we actually make significant strides and change the way things are viewed? Certainly there were successes and certainly there were failures.

“Difference is hard. Coming together across difference is the question before us as a country now and will be for a very long time.”

----------

‘All the Way’ and ‘District Merchants’

Where: South Coast Repertory, 655 Town Center Drive, Costa Mesa

When: “All the Way” continues through Oct. 2; “District Merchants” begins previews Oct. 2, opens Oct. 7 and ends Oct. 23.

Tickets: “All the Way” $30-$84; “District Merchants” $22-$79 (subject to change)

Information: (714) 708-5555 or www.scr.org

Twitter: @darylhmiller

ALSO

Ivo van Hove brings his stripped-down 'View From the Bridge' to Los Angeles

Amélie, Big Daddy, Hedwig: Familiar names hit SoCal stages this fall

Review: Resilience and dignity are the rich, bluesy music of 'Ma Rainey's Black Bottom'

Is August Wilson the 'Shakespeare of our time'? Cast and crew of 'Ma Rainey' say you can hear it

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.