Ayad Akhtar’s take on the Muslim experience in America

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — With an assured and intimate voice, playwright and novelist Ayad Akhtar’s stories cleverly slide across religion, tradition, sexuality and the dangerous if sometimes comical predicaments endured by Muslims in a post-Sept. 11 world hardened by incendiary politics and “us” versus “them” prejudices.

His work is intricately American, revealing the strains and joys of Muslims, many of them immigrants, trying to hold on to their ancestry while assimilating into a nation that celebrates diversity yet takes intense pride — and a degree of security — in counting the ways in which we’re the same.

Akhtar won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for his play “Disgraced,” the tale of a Pakistani American lawyer struggling with identity and repressed rage. The writer holds Islam and its followers and detractors up to a prism that exposes contradictions and unreconciled differences flowing beneath social and cultural veneers. His new play, “The Who & the What,” whose world premiere at La Jolla Playhouse runs until March 9, touches on similar themes when a daughter’s book about women in Islam and its portrayal of the prophet Muhammad riles her conservative father.

PHOTOS: The most fascinating arts stories of 2013

Playhouse Artistic Director Christopher Ashley said the work “tackles many hot-button issues surrounding religion and family traditions but with tremendous wit, warmth and wisdom.”

The son of doctors, Akhtar, a first-generation Pakistani American, grew up outside of Milwaukee. His well-received first novel, “American Dervish,” published in 2012, follows the young Hayat, who against his father’s wishes embraces Islam in a story of ideology, faith, fear and what gets stripped away and what remains as we mature. The novel includes a secular-leaning doctor, a fanatical imam and Hayat’s devout aunt, who is at once sexual fantasy and idealized virtue.

“The book to me is about the American religious experience,” Akhtar said. “It’s about a certain kind of rapture, a certain kind of violence and absorption and a capacity for ecstasy that I find particularly American.” The story draws from a country whose post-Enlightenment sentiments are twined with deep religious influences. “The Muslim American experience,” he said, “is a very novel and illuminating way to approach these things.”

Conservative Muslims have at times complained to him that his work is the equivalent of airing dirty laundry while giving voice to extremists and apostates, such as Hayat’s proudly anti-religious father in “American Dervish.” Much of this reaction reveals the fissures within Islam between moderates and conservatives, tradition and modernity, playing out in a permissive, predominantly Christian America.

PHOTOS: Faces to watch | Theater

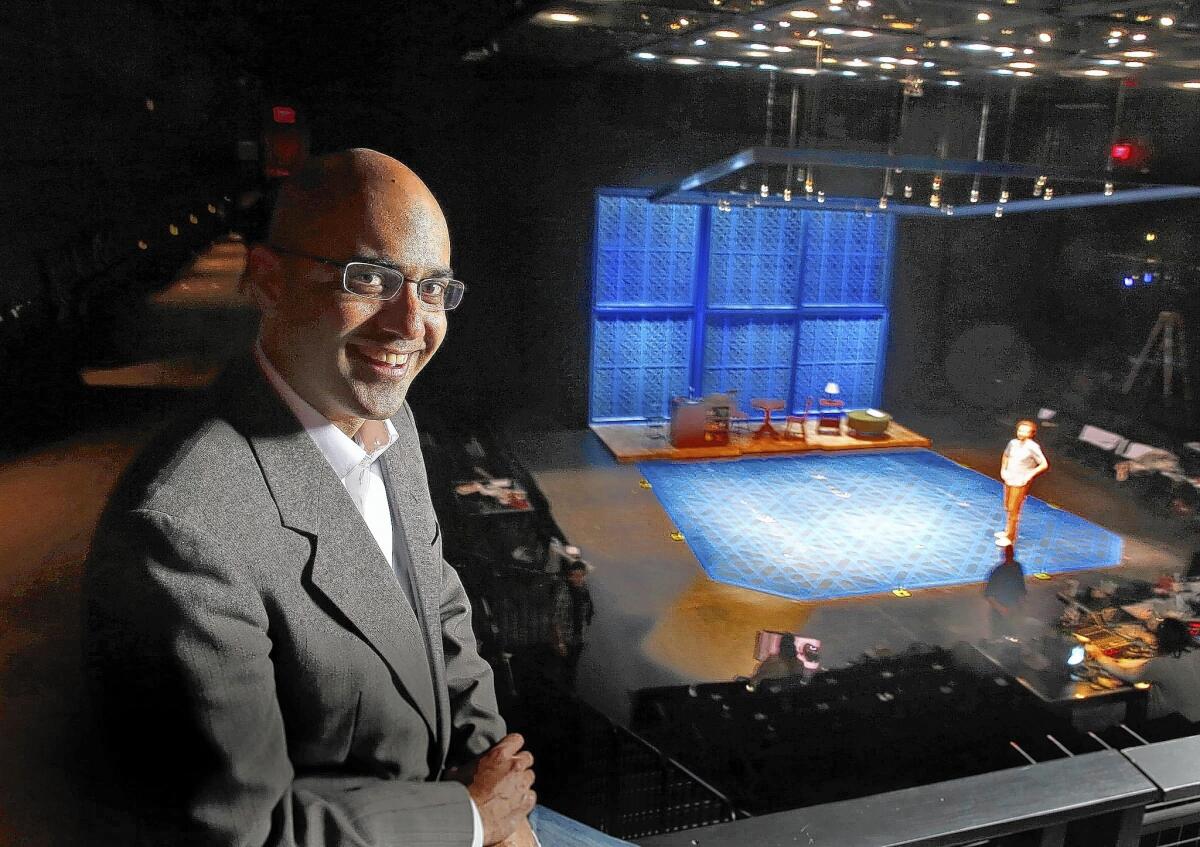

Akhtar, 43, is an intense man with a quick smile. He spoke recently during a technical rehearsal at La Jolla Playhouse, where actors framed scenes against a set of latticed windows. He veered from Egyptian politics to the philosophy of Langston Hughes and worried that his recent travels have taken time from his writing. He described himself as a “a nondenominational but very religious person.”

He said the Midwesterners of his upbringing were “good, open-hearted people.” He added that “I felt at certain times perhaps invisible. But I wouldn’t say I felt actively excluded. By invisible I mean in subtle ways.” He noted that “the girls I had crushes on” never imagined ending up with someone with “my skin color or my kind of name.”

Since Sept. 11, there has been a “hunker down and an understandably reductive way of looking at Muslims,” said Akhtar, who lives in New York. “The sense of subtle invisibility became a very, very prevalent visibility because of fear. Folks were suddenly afraid of someone who looked like me.”

He was inspired to write by a high school teacher who went through five husbands, tended 40 acres of farmland and had a passion for European modernism and literature. “She completely blew my mind open,” he said, adding that he was perplexed about what kinds of stories to tell until he learned that “writing about what you know is the way to the universal.”

PHOTOS: Best in theater for 2013 | Charles McNulty

After studying theater at Brown University, he lived in Italy and France, working with theater companies as an assistant director or acting coach. He wrote plays, screenplays and a novel, which he said he spent years on and believed in his “youthful exuberance” was the next “Moby-Dick.” It was not and remains unpublished. But his writing sharpened and his themes became distilled.

Amir in “Disgraced” is a New York corporate lawyer who shuns his Islamic roots yet appears not entirely comfortable in the Western trappings he has embraced. He is a man of contradictions, harboring bitterness, shame and prejudices that will shatter a Manhattan dinner party. Akhtar said Amir’s is a “tragic fall that was universal. Our capacity to remake ourselves despite the American mythos of happily ever after” ultimately comes at a cost.

The New York Times called the production at Lincoln Center Theater, a “vitally engaged play about thorny questions of identity and religion in the contemporary world, with an accent on the incendiary topic of how radical Islam and the terrorism it inspires have affected the public discourse. In dialogue that bristles with wit and intelligence, Mr. Akhtar ... puts contemporary attitudes toward religion under a microscope.”

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

The Daily Mail in Britain was less kind: A London production was “little more than a staged argument, and arguments make mediocre drama unless it really matters who wins,” its review said. “This is like watching a chatterati arts review on telly descending into insults and fisticuffs.”

Ashley said La Jolla Playhouse was excited to work with “a major new voice in American theater.” The play is directed by Kimberly Senior, who also directed the Lincoln Center premiere of “Disgraced.” The cast includes Monika Jolly, Bernard White, Meera Rohit Kumbhani and Kai Lennox.

During rehearsals Akhtar said he understood how his narratives and the passions they arouse could brand him a niche Muslim American writer. His mother advised him recently: “Ayad, you have to stop this Muslim thing.” But, he said, for now that’s where his stories lie.

“I’m continuing to grow as an artist and a writer. At a certain point, I’m sure I’m going to want to write about other stuff, [but] this is what wants to come through me.... If folks want to pigeonhole me as a Muslim American artist, hey, I’m just grateful anyone’s paying attention.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.