Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart on ‘No Man’s Land,’ parallel paths

- Share via

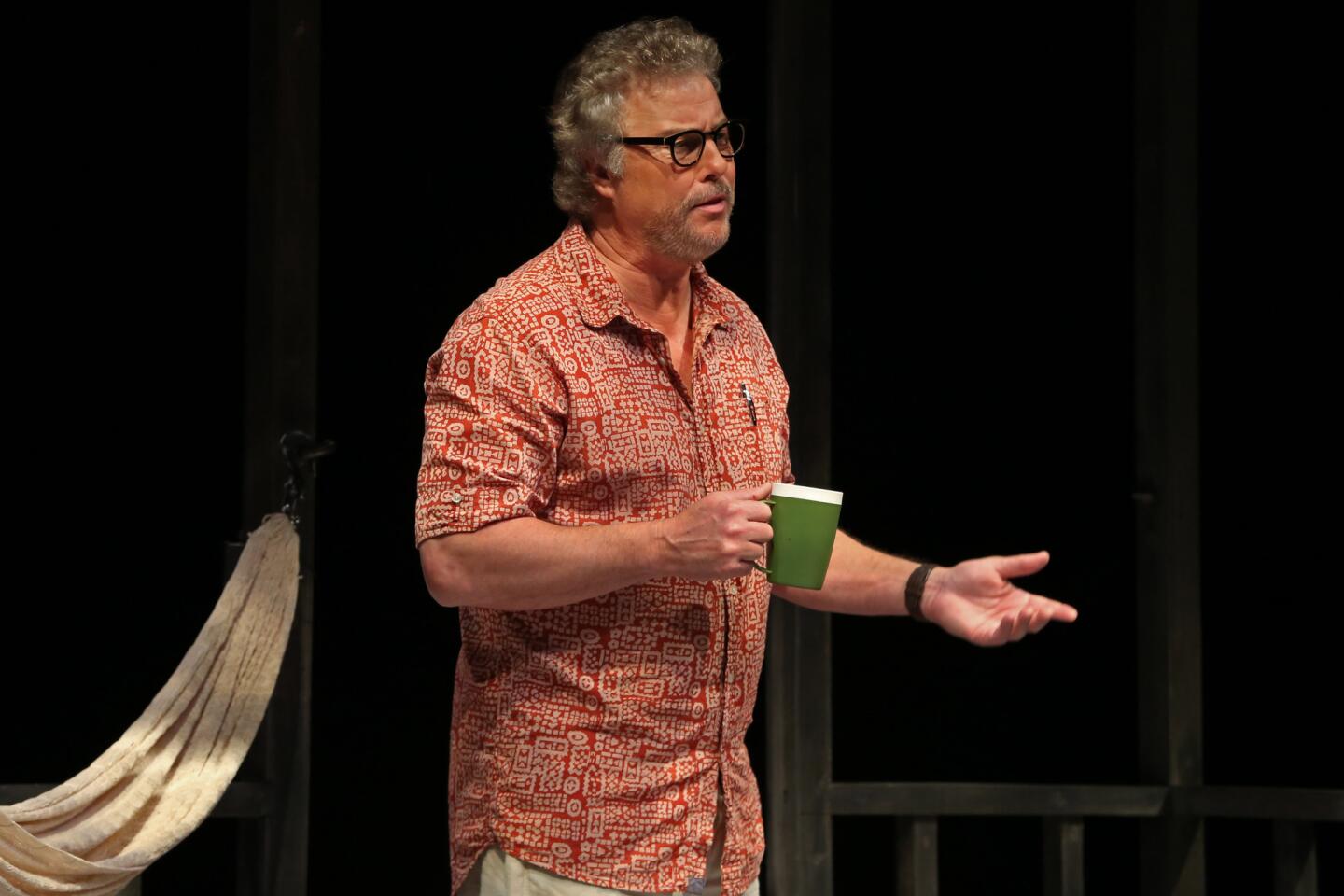

BERKELEY — Their Stradivarius voices precede them. Climbing the stairs for an interview following an afternoon rehearsal of their Broadway-bound production of Harold Pinter’s “No Man’s Land” at Berkeley Repertory Theatre, Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart announce their approach through the mellifluous flow of their conversation.

This is small talk you could bathe in, as clear and inviting as a fresh water pond on a lovely English summer afternoon. Consonants are caressed; vowels ripple joyfully through the air. These knighted gentlemen don’t need passports — a simple “good afternoon,” uttered in their instantly recognizable cadences, should clear them both through customs.

The room seemed distressingly ordinary for a joint interview with two legends of the British stage. But once Sir Ian and Sir Patrick settled into their chairs, the generic confines of this Berkeley Rep office seemed perfectly natural.

These veterans are accustomed to the no-nonsense practicalities of the professional theater. The worldwide fame granted to them by Hollywood franchises — “Star Trek: The Next Generation” for Stewart, “The Lord of the Rings” for McKellen, “X-Men” for them both — has been what McKellen calls “jam.”

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Stewart recalled that in the early days of his “Star Trek” series, when he was in denial about his newfound television success and living above a garage in Hancock Park, he started creating one-person shows to perform on weekends on college campuses in California, so terrified was he of losing his confidence in performing before a live audience.

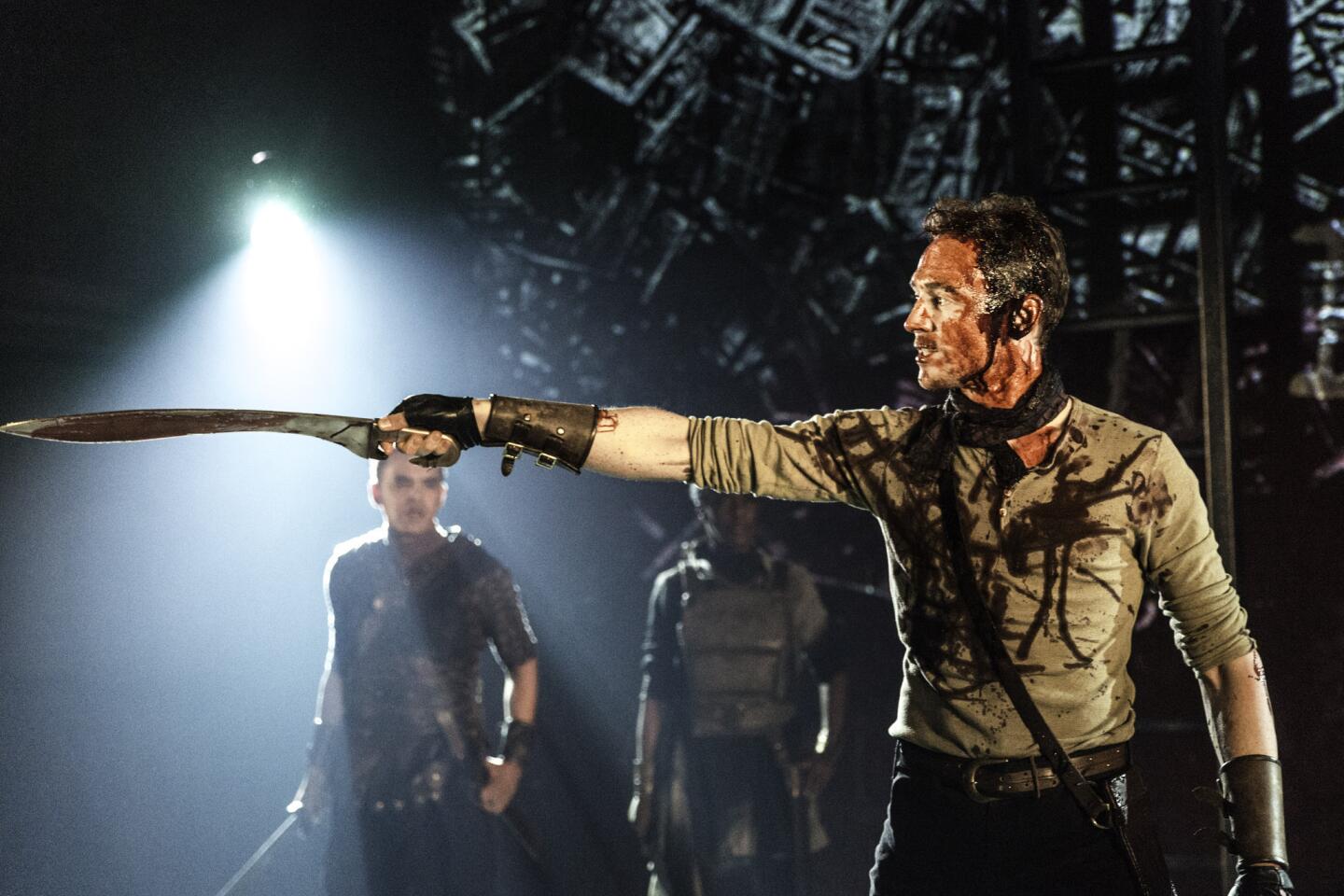

The stage will always be their natural habitat. Why else would these set-for-life septuagenarians opt to star in a defiantly enigmatic Pinter play — a work they will perform in repertory on Broadway this fall with Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” both staged by British director Sean Mathias.

Of course their role models are those British acting titans of the past who donned theatrical makeup well into majestic old age. Two in particular spring to mind — Sir Ralph Richardson and Sir John Gielgud, both of whom starred in the original London production of “No Man’s Land” in 1975 that subsequently came to Broadway.

Richardson originated the role of Hirst, the wealthy alcoholic poet that Stewart is now portraying. Gielgud originated the role of Spooner, the shabby alcoholic poetaster that McKellen is now impersonating. As precedents go, Richardson and Gielgud are the gold standard, but fortunately British stage actors of a classical bent don’t see tradition as a zero-sum game.

“Gielgud’s Spooner, more than almost any other performance I’ve seen, was indelible in here,” McKellen said, tapping his forehead. “I can do the whole performance as he had done it, and that’s how I started rehearsing it. I thought, ‘I shouldn’t be doing this. Gielgud has done it.’”

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

Stewart can still hear the gasps when Richardson’s Hirst fell to the floor. “There was about [Gielgud and Richardson], which I don’t think there is about the two of us, this sense that they were national treasures. And to see one of our national treasures crash to the floor in a play in which they had to say [expletive] and [expletive] was shocking,” he said.

The respect McKellen and Stewart feel hasn’t stymied them, however. “My impression of their performance was that they were a brilliant facade,” McKellen said upon further reflection. “Everything was there. You could admire it, you could be overwhelmed by it. But what you were seeing was the surface, and I think the play merits another approach.”

McKellen and Stewart, who worked together in the 1977 premiere of Tom Stoppard’s “Every Good Boy Deserves Favour,” earned plaudits when they met again onstage in “Waiting for Godot” in 2009 at London’s Theatre Royal Haymarket. McKellen was eager to bring the production to New York, but Stewart had his heart set on “No Man’s Land.”

“I had for 38 years loved this play and imagined one day I would do it but didn’t know where or how or under what circumstances,” Stewart said. “As Ian and I got to know one another very well during the period of ‘Godot,’ I felt as though the role of Spooner could have been created for him.”

According to McKellen, Mathias brokered a deal between the gentlemen by suggesting to Stewart that McKellen might agree to do “No Man’s Land” if Stewart would consent to another go of “Godot.” Thus the somewhat unusual repertory arrangement for Broadway, one that threatens to become a trend this fall with Mark Rylance heading the all-male Shakespeare’s Globe productions of “Twelfth Night” and “Richard III.”

McKellen’s doubts about “No Man’s Land” stem in part from the way the play, as he succinctly put it, “raises more questions about plot than an audience feels qualified to answer.” The dramatic situation of “No Man’s Land” is indeed mysterious in that poetically suspenseful manner that has come to be known as “Pinteresque.”

Hirst, having met Spooner in a pub earlier in the evening, has invited him back to his stately Hampstead home. It’s not clear whether these older gentlemen have known each other before, what the nature of their present business is beyond the frenetic consumption of liquor or why the two male employees who live with Hirst (played by Billy Crudup and Shuler Hensley) feel the need to subtly menace this visitor, who is desperate to be taken on board as a secretary.

The characters bluff and baffle while dispensing non sequiturs. Critics and scholars have sought valiantly to decode the play’s meaning. Is Pinter presenting a split image of the artist’s identity, one entombed in triumph, the other begging for alms, or could the power games have a more sinister, not to say sexual, implication?

Luckily, actors and audiences needn’t crack the mystery to enjoy the work: The greatness of “No Man’s Land” lies in its theatrical effectiveness — how well it plays. And McKellen and Stewart, whose Berkeley run ends Aug. 31, perform it like masters, their contrasting manners colorfully accentuating the differences of their characters.

McKellen in conversation is the more voluble, his fingers ever in motion directing the flow of his cascading fluency. Articulate in his own discreet fashion, Stewart has about him a beatific stillness, a gentle strength. These personal styles are in perfect complement in “No Man’s Land”: Stewart’s physical eloquence balancing McKellen’s verbal finesse.

Best of all is their sixth sense, sharpened by years of practice, for when theatergoers are in on the joke.

Peter Hall, who directed the original production of “No Man’s Land,” reports in his “Diaries” that Gielgud told Pinter that acting in his plays “was like playing Congreve or Wilde. It needed a consciousness of the audience, a manipulation of them which was precisely the same as for high classical comedy.”

“To hear audiences — and they’re bright in Berkeley — enjoy the play at the simple level of finding it amusing — I’m sure that’s just what Pinter wanted,” McKellen said. “He’s a master of language, rhetorical, poetical, but what anchors it for me is the comedy.”

Yet if spectators are free to enjoy the puzzling antics of the characters — all of whom are named after English cricket players in this sporting drama of offense and defense — the actors themselves cannot afford to be uncertain about who they are playing.

Did Hirst and Spooner really know each other at Oxford? Did Hirst seduce Spooner’s wife? Was Spooner ever even married? Does it even matter?

While acknowledging that it isn’t always helpful in Shakespeare, Beckett and Pinter to be “rooting around a character’s past if you aren’t getting the rhythm of a line right,” McKellen asserted, “We’re post-Freudian actors. I don’t know any other way to act.” To illustrate his point, he held up a wedding ring that he said belongs not to him but to his character.

“I wear it all through the performance so that anyone can pick up on it,” he said. “Yes, Spooner is married, though he doesn’t live with his wife anymore. When I boast of having a wife and children in the country, this is rather what he wishes he had but doesn’t anymore. “

Stewart expressed delight in McKellen’s revelation, explaining, “As we did with ‘Godot,’ we both have secrets that we keep from each other.”

Is there a connection between the Beckett and Pinter plays? Neither McKellen nor Stewart was inclined to hold forth on the existential meaning of these absurdist classics. Keeping it concrete was the priority.

“Hirst and Spooner meet in a famous pub,” McKellen said. “Jack Straw’s Castle was a real pub. These are real inhabitants of London. You can’t play an emblem. Other people can see what they like about the human condition, but in ‘Godot,” my guy is called Estragon, he has a friend called Vladimir, and they used to have a musical act called Didi and Gogo. That’s what we seemed to discover.”

The knights have become passionate public advocates — McKellen for gay rights, Stewart for bringing attention to the problem of domestic violence. Actors of their stature aren’t known for their selflessness, but there was a refreshing lack of ego in the room.

Dropping his voice as though to reveal a confidence, McKellen said, “Before the curtain goes up, I’m thinking, ‘I just walked over from Jack Straw’s Castle — I wonder how long it was. I wonder if I had to help him up the steps. Did I expect to be invited in and all those things?’ And then I look at Patrick’s back, and I think, ‘Oh, it’s going to be all right.’”

Stewart roared with laughter before saying, “This really is to Ian’s credit because before we started rehearsing ‘Waiting for Godot,’ he said, ‘You know, I think we should share a dressing room because we cannot begin this play when we meet onstage. We have to begin it at least a half-hour, 45 minutes earlier.’ I think this connected us in the ‘Godot’ and continues to connect us for this play.”

“Although we’ve not worked together often, we’ve been having parallel careers,” McKellen said. “We speak the same language, we know the same directors, we know the same dressing rooms, and the problems of playing Macbeth. And one of the things we have in common is that we’ll go on doing it as long as we’re allowed.”

Thankfully, there’s no shortage of mature characters. Hirst and Spooner are in their 60s, but they seem older, ravaged as they are by drink. As for Vladimir and Estragon, McKellen said, “The revelation of our production of ‘Godot’ is that old age is exactly what it’s about: one man has a prostate problem, the other has a problem with his feet and his memory. And we all know about those things.”

McKellen has been enjoying a television resurgence with his contemporary Derek Jacobi. The two have just completed the first season of the British sitcom “Vicious,” playing — trend alert — a bickering senior gay couple.

“All my friends hate it,” said McKellen. “Audiences who like it, like it enormously. It’s very old-fashioned, and Derek and I, we act something shamelessly in it.”

“If you’re lucky and you’re continuing to work as we have been lucky, then nothing is wasted,” observed Stewart, who said that he’s even been able to funnel the slight rheumatism in his hands into his performance in “No Man’s Land.”

McKellen quipped, “The joke is that you start in the company playing Barnardo in the first act of ‘Hamlet,’ then you graduate to play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, then it’s Horatio, then maybe Laertes and possibly Hamlet. Then you start playing Claudius and then Polonius — and then you play the skull, though we’re not quite there yet.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.