Los Angeles Opera’s ‘Billy Budd’ cast learns how to survive a hanging

- Share via

Under the Articles of War enacted by the British Navy in the 18th century, many crimes qualified as capital offenses, including mutiny, treason, robbery, sodomy and murder. Executions were often carried out by hanging, with the convict strung up from the ship’s yardarm.

By accounts from that era, these hangings were more a gradual strangulation than a snap of the neck. They were also complicated, requiring several men to hoist and secure the convict at a considerable height on a moving ship.

The climactic hanging in Los Angeles Opera’s revival of “Billy Budd” — opening on Feb. 22 — is also complicated, though for different reasons. To simulate the look of a naval execution, the company’s production team has laboriously rehearsed the sequence in which baritone Liam Bonner as Billy is hoisted and left suspended 12 feet above the set.

PHOTOS: LA Opera through the years

The scene is treacherous enough to necessitate the presence of the production’s original director, Francesca Zambello, who first mounted this staging in 1994.

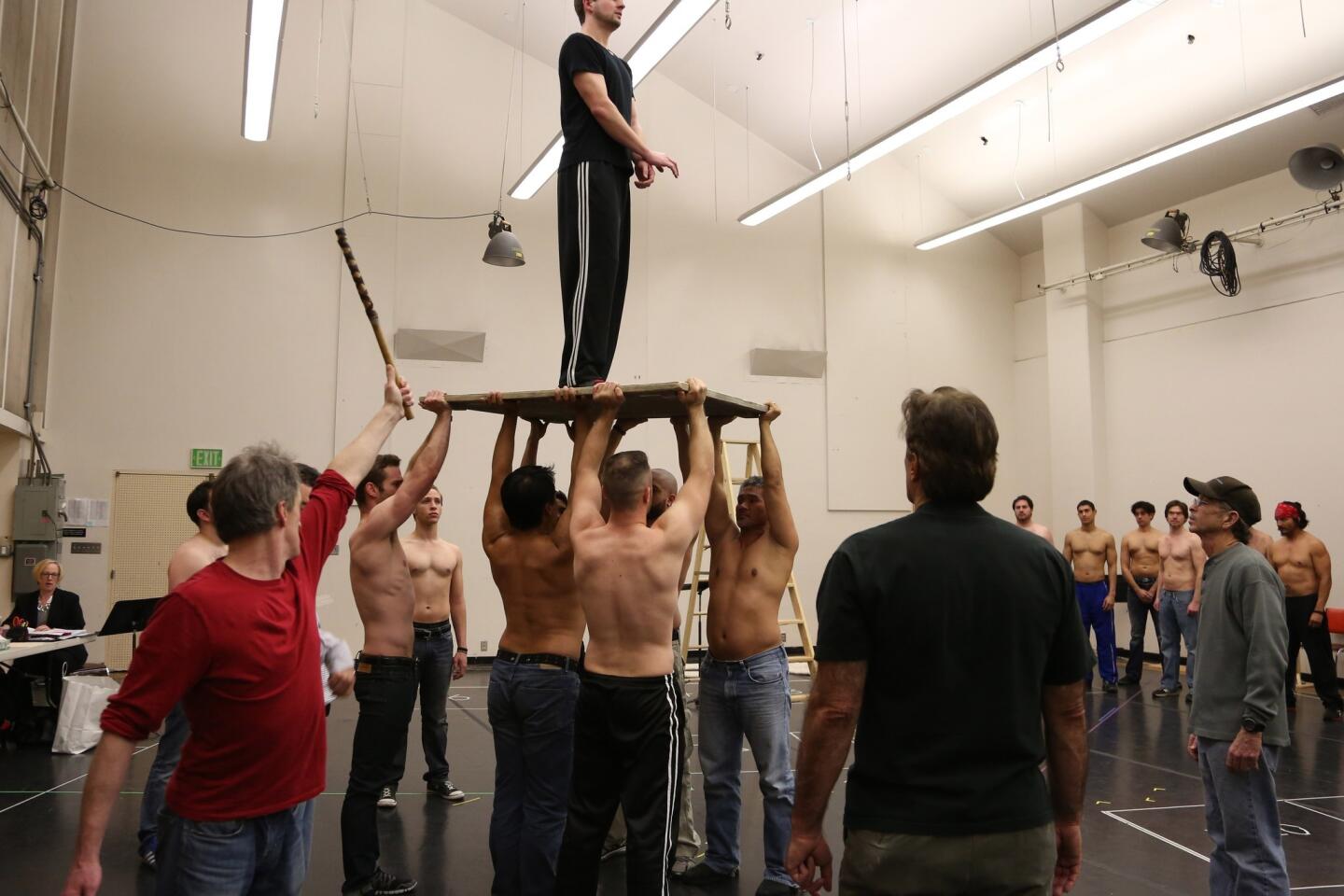

Bonner stands on a wooden plank and is hoisted by six male performers who must coordinate their movements or risk having the star tumble onto the steeply raked set. They must then drop the plank from under his feet in unison at the moment of execution.

In a recent rehearsal, Zambello had the performers practice their moves several times — first without Bonner and then with the singer, who didn’t wear any safety gear despite the real possibility that he could fall off and injure himself. Lifting the singer was no simple task — he stands 6 feet, 4 inches tall and weighs 190 pounds.

“How do you feel, Liam?” asked Zambello when the singer was fully hoisted in the air.

“I’ll feel good when I’m hooked up to the cable,” he replied, referring to the safety device that will be used during performances.

Height is a crucial aspect of this “Billy Budd.” The protagonist is tall, handsome and charismatic. The vertically oriented set represents the swaying mast of the HMS Indomitable. And the production itself is the pinnacle of L.A. Opera’s yearlong centenary tribute to composer Benjamin Britten, born in 1913.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

“It’s an ideal choice of subject for an opera — it’s a universe contained in a universe [on this ship],” said L.A. Opera music director James Conlon. Surprisingly, he is conducting “Billy Budd” for his first time. “It wasn’t deliberate. Things sometimes happen that way in opera.”

In the last 12 months, Conlon has led local performances of several Britten works, his “War Requiem” and “The Rape of Lucretia.” In recent seasons, L.A. Opera has staged the composer’s “The Turn of the Screw” and “Albert Herring.”

“James and I wanted to follow those two operas with one of his biggest works,” said Placido Domingo, the company’s general director.

“Billy Budd” is epic — a tale of innocence destroyed on the high seas. Adapted from the novel by Herman Melville, the story follows a young sailor who is beloved by his crew members but whose youthful charisma earns him the enmity of his superior, the master-at-arms Claggart (bass-baritone Greer Grimsley).

The opera was also a personal one for Britten for its homosexual subtext. (The composer was gay and lived at a time when homosexual acts were criminal in Britain.) The sublimated attraction that Claggart feels for Billy plays out in an all-male setting, though Claggart never articulates any sexual longing.

PHOTOS: Gay celebrities — Who’s out?

The degree to which they should show the attraction was a matter of some dispute among the opera’s creators, according to a recent article that Conlon wrote for the Hudson Review.

E.M. Forster, the author of “Howards End” and “A Passage to India,” among other works, wrote much of the libretto for the opera. Forster, who was also gay, wanted Claggart’s homoerotic feelings for Billy to be more directly expressed and said so to the composer.

But Britten resisted making the changes, apparently preferring audiences to read between the notes.

Zambello said during a break in rehearsal that she hasn’t made the production more overtly gay in the 20 years since she first staged it. “I don’t think you do it more ‘out,’” she said.

Nonetheless, the production features moments where the homoeroticism surges to the fore. During a run through of the trial sequence, in which Billy is convicted for striking and killing Claggart, she directed the singers to be more overtly physical.

“Yeah, grab him. Inappropriate behavior,” she told one singer during a particularly impassioned exchange. “There’s a little bit of buggery going on there, right?”

Zambello’s stay in L.A. was brief — she rehearsed scenes for a week and then handed off the duties to assistants and left for Switzerland, where she is directing the new Frank Wildhorn musical “Excalibur.”

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

She juggles her directorial jobs with administrative posts as the head of the Glimmerglass Festival in upstate New York and the Washington National Opera.

“Billy Budd” was first performed in London in 1951 in a much longer version than the two-act opera that is customarily staged today. Zambello’s production won an Olivier Award when it premiered in London in 1995. Michael Grandage’s production from 2010 recently played at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where it received rapturous reviews.

The hanging sequence represents a technical challenge for any production, though many have opted to leave that moment offstage.

When Bonner is elevated for his character’s execution, he will be wearing a custom-fitted harness made of nylon webbing and designed to fit snugly under the singer’s costume, according to Rupert Hemmings, the company’s director of production.

A cable will be attached to the harness that will secure him in midair after the plank he is standing on drops.

For audiences, the site of Billy’s body will be brief before the lights go to black and the story enters the epilogue delivered by the ship’s Captain Vere (tenor Richard Croft).

In the original novella, left unfinished after Melville’s death in 1891, the author provided a description of his hero’s lifeless body.

“No motion was apparent,” Melville wrote. “None save that created by the ship’s motion, in moderate weather so majestic in a great ship ponderously cannoned.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.