‘Hateful Eight’s’ Quentin Tarantino, Samuel L. Jackson touch raw nerve of racism

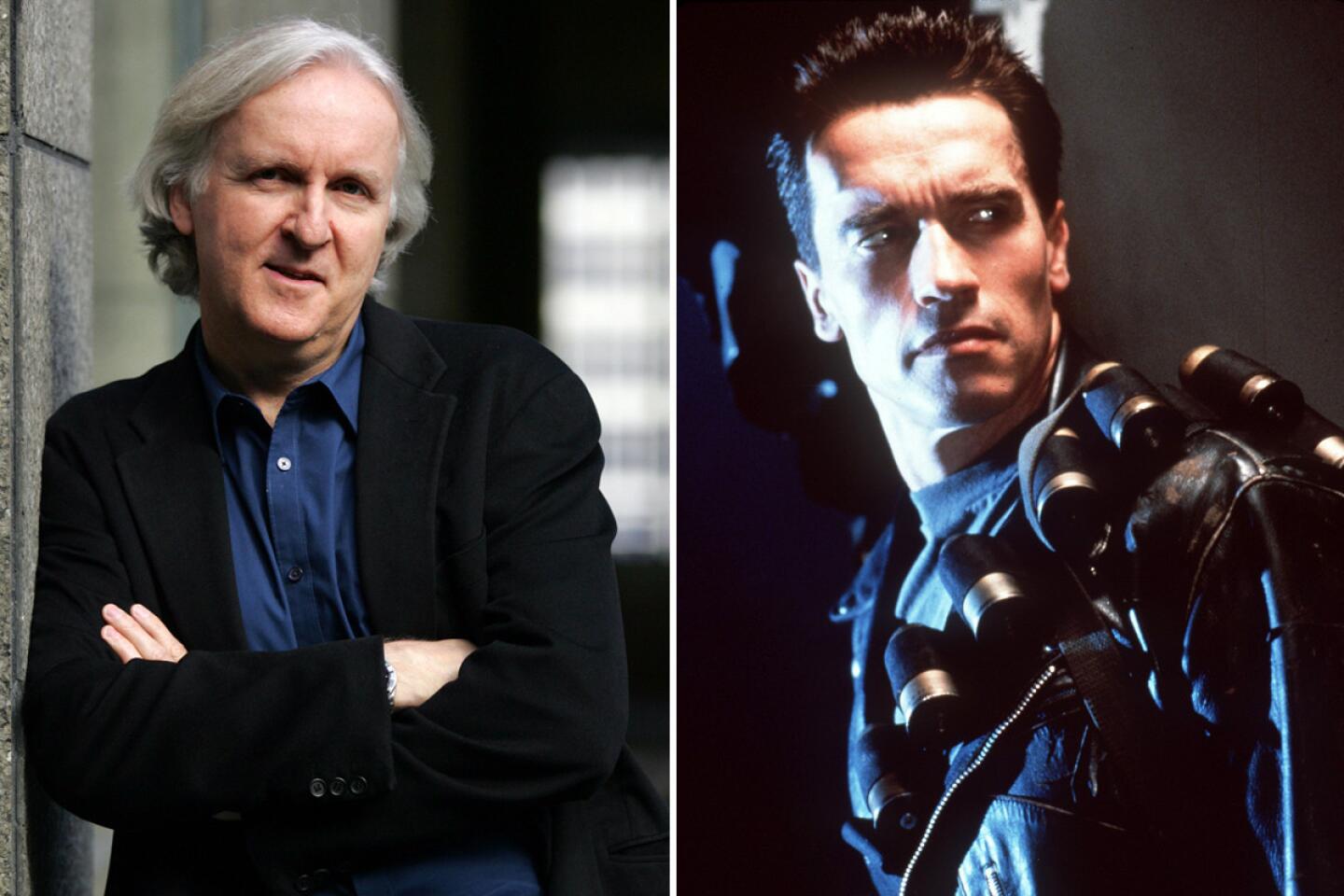

“As an artist you can only hope to do some piece of material that actually connects to the zeitgeist,” says Quentin Tarantino, left, with Samuel L. Jackson.

- Share via

Out of a nation shaken by terrorism, racial tension and violence, where traces of past sins collide with a quicksilver pop culture, rides Quentin Tarantino’s new film about frontier justice, strange alliances and how a black bounty hunter with a dead-eye shot survives on guile, menace and clever sleight of hand against enemies and unrepentant Confederates.

“The Hateful Eight,” which opens Christmas Day, is a western spun through a racial prism, a swift-talking tale of seven suspicious men and one mean woman trapped in a snowstorm in the cruel mountains of Wyoming. The bad die in wicked ways and mercy is a lie, but the film, set in post-Civil War America, speaks to today’s troubled landscape of police shootings and seething politics.

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Tarantino turns narratives inside out and scratches at the national psyche with restrained frenzy. Like his other films, notably “Pulp Fiction” and “Django Unchained,” “The Hateful Eight” hypnotizes with dialogue while edging toward brutal recrimination that is at once wincing and cartoonish. The movie, brimming with N-words and ghosts of the Old South, distills the disquieting polarization of a country that has given us Donald Trump and Black Lives Matter.

Filmmakers are often reluctant to draw analogies between their work and divisive current events. But Tarantino relishes hitting nerves and insinuating himself into the broader conversation.

“The events in the world are disturbing to say the least, but as an artist you can only hope to do some piece of material that actually connects to the zeitgeist,” Tarantino said. “While we were doing the movie that sort of blue state-red state divide that had been going on — and it wasn’t lost on me when I wrote the script — just got wider and wider and the people on both sides of the line seemed to be even more vocal in demonizing one another.”

Talking to Tarantino is like buying a car from a man at the end of an alley. He’s coy, quick, effervescent. He has a prankster’s laugh, and his long frame, tailored in gray and black, unfolds like a loosed hinge. He sat in a Beverly Hills hotel as dusk fell over Hollywood Hills and President Obama addressed the nation after the San Bernardino shootings. The director had been talking to the press about his film for three days, and it seemed he could go for three more.

Samuel L. Jackson took a seat beside him. The two have collaborated for decades, and in “The Hateful Eight” Jackson is Major Marquis Warren, an ex-Union soldier and bounty hunter who relies on his wits, pistol and a suspect letter from Abraham Lincoln. Theirs is a relationship rooted in a reverence for film and Jackson’s loyalty to the director even as many blacks have criticized his portrayals of African Americans.

Both men escaped to movie houses when they were young, and, with Tarantino shaking his head, Jackson, 66, his voice like swallowed thunder, remembered his boyhood in Tennessee.

“I came home and I pretended to be the thing I saw up there because it made me feel good and it was exciting,” he said, gesturing toward Tarantino. “Those are the kind of movies he makes. He writes things that are complex, interesting and exciting. I don’t get a lot of those things. I get a lot of stuff. Very few scripts are those things.”

Anticipation for the movie, shot on high-resolution 70mm film with an overture by Ennio Morricone, has been strong. It received several Golden Globe nominations, including for screenplay, and is part of an aggressive Academy Awards campaign by the Weinstein Co. Despite his contentiousness, Tarantino, who threatened to shelve the movie after the script was leaked online in 2014, is a favorite among academy voters — he’s won two Oscars for his scripts for “Django Unchained” and “Pulp Fiction,” which he shared with Roger Avary.

“The Hateful Eight” glides on greed and betrayal played out in Minnie’s Haberdashery, an outpost in a blizzard where eyes squint hard and little is as it seems. The film also stars Tim Roth, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Kurt Russell, Walton Goggins, Michael Madsen and Bruce Dern, playing a bitter, white-haired Confederate general. They are a pernicious lot guided by the harsh codes of an untamed land where a hangman roams for hire and the sheriff has the oily manner of a corrupt preacher.

Racism and barbed vernacular — sentences flit like venomous sparrows — salt this mendacious stew. Major Warren is the only black among whites, some of whom tolerate him while putting him in his place with the N-word, and others who would just as soon lynch him. The major is wily enough to know that safety is a black man’s delusion, which is why he keeps his weapon close and an ever-assessing gleam in his eyes. He uses the color of his skin and all it evokes to scare, revile, placate, humor and draw respect.

“If I have one serious subject that has carried over with me,” said Tarantino, 52, “it is dealing with race in America and in particularly between white folks and black folks.... It is who I am and what I’m interested in.”

Black writers and intellectuals have upbraided Tarantino for warping black history and offending with caricature and epithet. One of his most vocal detractors has been Spike Lee, a director whose vision and cinematic alchemy are as captivating as Tarantino’s. Both filmmakers explore race; Lee’s new movie “Chi-Raq”, which also stars Jackson, bristles with street violence and the N-word in Chicago. But Lee vilified “Django Unchained,” about a black slave turned gunslinger, in a tweet: “American slavery was not a Sergio Leone spaghetti western. It was a Holocaust.”

“What’s most offensive is that [Tarantino’s films] are being treated as a guide to black history,” said Ishmael Reed, a writer and activist who recently edited “Black Hollywood Unchained,” a collection of essays on how African Americans are portrayed in films. “Tarantino gets more coverage and a bigger audience. There aren’t enough black directors with enough power to accurately tell the story of black history.”

Such criticism doesn’t “deserve much respect from me,” said Tarantino, suggesting that his opponents want to appropriate racial and cultural touchstones to keep them out-of-bounds for white artists. “I’m a writer. Writers are supposed to write about themselves and other people. Male writers are supposed to write about white people and black people and children, women and old people.”

Tarantino has a sharp awareness of the times and a savant’s detailed passion for movies. He is a “provocative artist and filmmaker,” said Yoruba Richen, a black documentary director. “What I appreciate about him is that he’s engaging with issues of race. I don’t always like what he does, but I’m interested.”

Dressed in a burgundy cap and a matching sweater, Jackson took the argument back to his Chattanooga childhood when his grandfather, who cleaned offices, was referred to as “boy” and worse by white men. He said in the South everyone professed to hate the N-word. “But every rap song has it in it. It’s all over ‘Chi-Raq.’ It’s all over ‘Straight Outta Compton.’ So what are we talking about?”

He pointed to Tarantino. “He’s not that person,” he said in answer to those who accuse the director of racism. “He’s not any of those people.”

In October, Tarantino outraged police unions across the country when he marched in New York to protest police brutality against blacks. “I’m a human being with a conscience,” Tarantino said at the rally. “And when I see murder I cannot stand by. And I have to call the murdered the murdered and I have to call the murderers the murderers.”

Police threatened to boycott “The Hateful Eight.” Days later, Tarantino told The Times: “All cops are not murderers. I never said that. I never even implied that.”

But the San Bernardino shootings — carried out by husband and wife Islamic radicals — have tugged the nation, at least for a time, in a different direction. Tarantino and Jackson spoke of the paranoia that blooms from fear and how racial and cultural pecking orders get rearranged. Mentioning that even today he is deferential to police because of what he learned as a boy, Jackson wondered what Muslims in America might encounter in the coming months.

“They’re not your neighbors anymore. They’re suspects,” he said, suggesting what may be in the minds of many. “They’ve essentially become young black men in a community where before they didn’t have to walk the line. People fear them in a way they didn’t before.”

Tarantino nodded. He sipped water. Jackson leaned back. They were friends, muses, guys used to being holed up for months together. As kinetic as they are, both men, on-screen and in person, have the patience to let a moment gather force. Jackson remembered his youth, sitting on the porch with his grandfather, listening to Andy Griffith on the radio, trying to figure out how a story works, how it crawls into you and makes a home. Tarantino said he wanted to make another western so his work could stand on a shelf with Anthony Mann and Sam Peckinpah.

He turned to Jackson.

“He does dialogue like nobody else,” he said of the actor. “I let him do more collaborating with the structure of the scene and even some of the dialogue and even some of the emotional beats than I allow other actors to do. He’s plugged into the way I write.”

Tarantino stood and stretched. Night covered the hills. Obama’s speech was over and pundits were spinning what it all meant. From the 15th floor of the hotel, the world below unfurled in the bittersweet quiet of a dying Sunday; makeup artists packed their bags and publicists scratched the last names off their lists. Jackson pulled tight his cap and walked to the door.

Television sets flickered with the latest violence from militants in Iraq and Syria, and a day later protesters in Chicago condemned the police shooting of a black teen.

Twitter:@JeffreyLAT

------------

3 Quentin Tarantino films about race

Quentin Tarantino’s films hurtle with violence, sly dialogue, multiple storylines, references to pop culture and explorations of inter-racial relationships among everyone from married couples to hit men. Tarantino has often been criticized by black intellectuals and writers, including director Spike Lee, for his depictions of African Americans and their history. The director’s supporters say his work uses the n-word and confounds stereotypes to bring race into sharper, more realistic focus. These three films showcase Tarantino’s controversial depiction of race:

“Pulp Fiction” (1994): This free-wheeling, verbally charged take on con men, crime lords and other malcontents is rife with racial overtones. It weaves several narratives, including the dynamics between hit men played by Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta, who wax philosophical as bodies fall and blood is mopped up. It’s brazen in its use of the n-word, notably by a husband (played by Tarantino) married to a black woman.

“Jackie Brown” (1997): Starring Pam Grier, the sultry queen of 1970s blaxploitation movies, the film traces the travails of a flight attendant contending with federal agents and gun dealer Ordell Robbie (Jackson). Robbie brims with racial asides, likes a video called “Chicks ‘n’ Guns,” and is fond of the AK-47 for when “you absolutely positively got to kill every [expletive] in the room.” The screenplay is based on Elmore Leonard’s novel “Rum Punch.”

“Django Unchained” (2012): Tarantino’s most racially unsettling tale, the film follows two men: A German bounty hunter who detests slavery (Christoph Waltz) and the black gunslinger (Jamie Foxx) he befriends. The men set out to free Foxx’s wife from a vicious plantation owner (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his malevolent, plotting house slave (Jackson). The movie is saturated in violence and vengeance, leading to questions about the deceptions, betrayals and cruelties wrought by slavery.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.