- Share via

David Milch sat in a Playa Vista restaurant, eyeing a small cheese pizza in front of him. The story he was telling is true.

“I was running bets for my old man and half a dozen people when I was a boy,” Milch said, flashing a soft smile at the recollection of hanging out at the racetrack. “They’d tell me, ‘Bet $10 on the seven horse and shut up!’ For the big races, it was frightening, carrying around $1,000 when I was 7 years old.”

Encouraged by his companions in the nearly empty restaurant — Rita, his wife of 43 years, and his good friend, John Hallenborg — Milch continued to weave his memories of those bygone days into indelible images: magnificent horses thundering across the finish line and “degenerates” wagering staggering sums.

In many ways, it was a familiar scenario. Telling vivid stories populated with colorful characters, good and not so good, has been the defining work of Milch’s life. That ability made him royalty in Hollywood as he wrote for the classic police procedural “Hill Street Blues” and created provocative fare such as the gritty cop drama “NYPD Blue,” with Steven Bochco, and the acclaimed neo-western “Deadwood.”

But this was not just a casual lunch to indulge in nostalgia.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

While Milch, 78, can still tap into his past to construct a compelling yarn, his thoughts are filtered through a degrading lens. In 2019 he disclosed that he has Alzheimer’s disease. After being at the center of the TV world, his career came to an abrupt halt. Many in the legion of friends and associates who used to surround him when he was a big shot gradually drifted away.

“I’m losing my facilities,” he wrote in his 2022 memoir “Life’s Work,” composed with the help of his wife and children. “I wonder, and not infrequently, ‘Is it gone for good?’ My mind.”

But as he picked at his pizza, Milch demonstrated that his mind is far from “gone.” His vibrant spirit and artistry are thriving in a manner that might surprise the families of those affected by the degenerative disease.

David Milch has a new screenplay.

For more than a year, driven by a dual mission of keeping Milch’s artistic muscles alive and shattering the stigma that shadows those who suffer from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, Rita Milch and Hallenborg have established a routine of working lunches intended to stimulate the TV legend’s creative juices.

“Work is at the core of David’s spirit — it’s his essence,” she said, sitting next to her husband at one of the lunches. “I really don’t care about the end result or whether this gets made.” The idea, Hallenborg added, “is to keep David engaged and bring him a source of joy.”

The result, a feature called “The Last Horsemen,” could return Milch to the spotlight nearly five years after his last produced credit, “Deadwood: The Movie,” was released.

It’s another unexpected twist in the life journey of Milch, who was known not only for his considerable showbiz triumphs but also his notorious dark side. In addition to being diagnosed with bipolar disease in the early 1990s, his addiction to gambling and drugs did extensive damage — he lost millions at the track and on sports betting. His volatile personality made him feared on and off the set.

:::

“The Last Horsemen” is the realization of a Milch story that was never developed, a narrative set in the horse racing world that centers on a corrupt gangster and his son and their impact on a young couple. Like other Milch projects, it contains raw language, complex relationships and unflinching violence.

Elements of the story came together as Rita Milch was focusing on “Life’s Work.” “David would ramble and tell me stories, and it was often the same story,” she told The Times. “It was often David’s story in different manifestations, and the characters were often him and his father. David was abused as a child. It was like all these things that he’d been working through his whole life.”

“There was the outline of a story he would keep coming back to,” so she called Hallenborg, who had worked with Milch on various projects. “I needed someone who could turn that outline into script form,” she added.

She trusted Hallenborg, who had been visiting Milch at the assisted living facility where he now resides. In addition to writing, their bond was built on their mutual love for horse racing — they’d spent numerous afternoons at the track — and their shared experience with addiction.

“Rita told me that David was absolutely animated about this story,” Hallenborg said.

At lunches during the next year, the tale was fleshed out. “We’d ask David, ‘What do you think of this?’ And it will be like the click of a light on his face,” Rita Milch said. “I push ‘record’ on the phone, and it goes from there. It’s jumbled and confused, but in there is a kernel of something that’s real David.”

She would email the recording to Hallenborg, who “would take from that the gold that David had mined” and incorporate that with his own voice.

“David, I want to talk today about happiness for gamblers,” Hallenborg said at one outing. “Did you feel happiest when you won at the track, or were you anxious to parlay your winnings back into the game?”

Milch replied that he “didn’t feel any imperative to prove myself again.”

“I think David is happy for a brief time when gambling ... minutes, hours,” Rita Milch offered. “His high was being at risk, having everything on the table.”

“Absolutely,” Milch said.

“When he was happy, I was happy,” she continued. “But no, I didn’t enjoy the gambling.”

“She felt the danger, even at a remove,” Milch said.

At times, the memories came flooding back. “My dad was a big tipper,” Milch said. “He would take me down to the winner’s circle, carrying me.”

Recalling how he got more serious about gambling in high school, Milch said, “My old man tightened up the cashier to carry his bets. And “I would have a little action on the side. There was so much action going on. At some level, I became an irritant because I was carrying all this stuff, and sometimes I would forget.”

Although he was quieter at other moments, Milch was attentive as Rita Milch and Hallenborg exchanged stories. “Even when he was working at the office, David was keeping tabs on what was happening at the track,” Hallenborg said. “He would send people to the track to place his bets or pick up money. He would talk to the trainers.”

“Now I’m the wretched wretch you see before you,” Milch quipped, much to the delight of his table mates.

:::

Rita Milch and Hallenborg were both stunned by Milch’s enthusiasm when they presented him with pages of the script. They said his sharpest talent, still, is shaping and editing screenplays.

“He’ll just start in on them,” she said. “I compare it to a musician playing an instrument. He just starts riffing. He can still bring the magic, even though he’ll forget or get disconnected.”

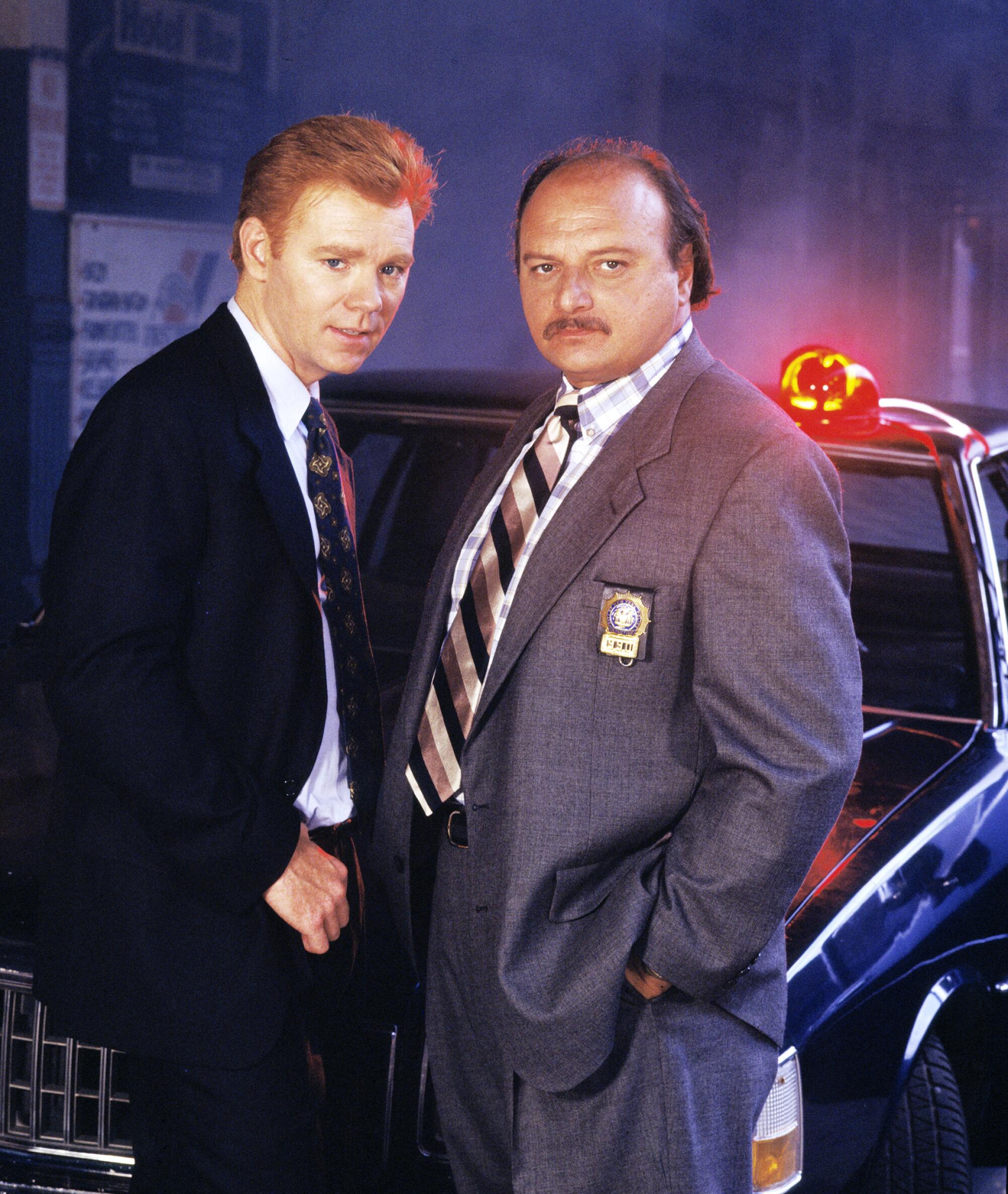

That disconnection is visible in one draft of “The Last Horsemen.” While making notes around lines of dialogue, Milch suddenly segued into composing a scene for “NYPD Blue,” which includes exchanges between Det. Andy Sipowicz (played in the series by Dennis Franz) and other characters from the ABC TV show, which ran from 1993 to 2005.

As “The Last Horsemen” script reached its final stages with Milch adding his notes, Rita Milch had other contributions and insights on characters that significantly improved the story, Hallenborg said. After those additions, they thought maybe, just maybe, “The Last Horsemen” might have enough commercial appeal to be produced.

While the screenplay is shopped around, the focus of the unusual partnership has switched to an idea hatched by Hallenborg that he hopes will lead to a TV series. The story is inspired by two young men he met on social media — one who has been in recovery and another who has been in and out of prison.

“He’s a fascinating, talented, handsome, smart, charming sociopath,” said Hallenborg of the second man. “I’m 38 years sober, but prior to that I had plenty of association with people who were outlaws. This is not unfamiliar ground to me.”

Gambling and racetrack shenanigans are once again a key part of the narrative, and Hallenborg continues to prod his former mentor with questions about his racing past and the culture of gambling, using those details to add authenticity to the new story.

Hallenborg, who has a 40-year background as a freelance writer for business publications, is open about his own ambitions, keenly aware that any successful project that links him with Milch will heighten his own profile in Hollywood. He has optioned three screenplays that were never produced.

Even so, his work with Milch has an emotional element that’s much deeper than any suggestion of fame or finances. Milch helped support Hallenborg years ago when he was in treatment for prostate cancer and could not work, once prepaying him for two scripts that were never developed. Their new partnership is Hallenborg’s way of returning the favor.

“From a spiritual standpoint, this is the most rewarding work of my life,” Hallenborg said. “Yes, it would be great if this would lead to something. But my No. 1 priority is to keep David’s engine going.”

At one of their recent outings, Hallenborg expressed awe at what the trio have already achieved in helping to craft “The Last Horsemen”: “Sometimes a little inflection from David, something that he just adds, will give insight into characters that was not there before. That is the magic of the guy.”

Rita Milch reached out and affectionately stroked her husband’s hair. “See, Dave? You’re magic.”

Milch nodded his head and smiled: “Shows you what prison can do.”

That exchange could easily fit into a Milch-penned drama, although it’s hard to reconcile the mild-mannered person who slips $10 to the waitress before she even takes orders from the table (“Please indulge him — it’s important,” Rita Milch advises the startled server) with the fiery force of nature who once referred to himself in an essay for young screenwriters as “David f— Milch.”

:::

Although Rita Milch is heartened by her husband’s ability to remain creative at this stage of the disease, she acknowledges a harsher reality.

“David’s mind is getting harder and harder to get to,” she said later. “It’s heartbreaking. He’s leaving, piece by piece. He lives in a state of agitation, brought on [by] a sense of unfulfilled obligations. He has paranoid moments, which is common with dementia.”

That agitation can be explosive, as evidenced by an early-morning visit to the assisted living home. Hallenborg had arranged with Milch in advance to go over some script pages based on conversations the pair had a few days earlier.

But minutes after Hallenborg escorted Milch from his apartment to a conference room, it became clear that something was not right. Milch frowned as he riffled through the pages.

“Why haven’t I seen this before?” he finally asked.

“Because I just wrote it,” Hallenborg replied.

After a few tense minutes, Milch grew more confused.

Realizing the strain, Hallenborg apologized: “I tried to call you earlier, David, and there was no answer. You said I was imposing when I came to your room to get you, and that was not my intention.”

“Well, your intention is not the be-all and end-all,” Milch snapped.

“I never said it was.”

“YOU JUST DID!” Milch fired back. “You just gave me this to read, and I don’t know what the f— it is.”

“OK, I apologize for imposing on your morning,” Hallenborg said calmly. “It was not my intention to do that.”

“It wasn’t?”

“No, David. I’ve stopped by here many times. Today there’s friction and bad communication between us and I have to accept that. I really am sorry for imposing on you.”

“If you were really sorry, you wouldn’t have done it!”

After returning Milch to his room, Hallenborg said the encounter would have been smoother if Rita Milch had been present. It’s a mantle she’s become used to wearing.

“In horse racing, there’s the goat, which is to keep the horse calm,” she explained. “If I’m there, David can reach out and put his hand on my knee, and that will make him feel better. I see that as my role — the calming influence.”

Milch’s current situation might be compared to the later years of Tony Bennett and Glen Campbell, popular singers who were able to keep performing years after they were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Monica Moreno, senior director of care and support at the Alzheimer’s Assn., said Milch’s ability to access his talent for storytelling is similar to the experiences of the two singers.

“His ability to be a TV writer and producer was such a huge component of who he is,” Moreno said. “Considering the work he had in this area, it’s not uncommon to see where they’re discussing things he’s done his whole life that it stimulates those memories and allows him to engage.”

:::

Milch first made his mark in the 1980s as a writer and executive producer on “Hill Street Blues,” which was co-created by Bochco. He and Bochco went on to co-create “NYPD Blue,” which broke network barriers, and frequently stirred controversy, with its foul language and nudity. The series was a massive hit and won numerous Emmy awards.

Milch’s creation of the HBO series “Deadwood” in 2004 was another success, proving that he could extend his writing prowess far beyond the urban milieu of police precincts and crime scenes. The revisionist western, set in the real-life mining town of Deadwood, S.D., starred Timothy Olyphant and Ian McShane at the head of an ensemble of evocative characters and was marked by brutal violence and toe-curling obscenities, often projected with Shakespearean flair.

After “Deadwood,” though, Milch struggled to match his earlier accomplishments. In 2007, HBO yanked his trippy surfer family drama “John From Cincinnati” after just one season, and the premium network also canceled his 2012 horse racing drama “Luck” after one season when three horses died during production.

Work was one of Milch’s addictions, Rita Milch said. “It was all very intense, and that’s probably a part of the attraction — this heightened sense of reality. He worked seven days a week for all his working life. We lived separate lives, but it was always intense and scary. We would be walking on eggshells.”

A typical day now for Milch begins in the morning, when he will read and edit scripts and manuscripts. “People bring him stuff to read, and he’ll go over pages with a pencil,” said Rita Milch, who visits him several times a week.

“People ask me about him all the time,” Hallenborg said. But “he doesn’t get many visitors, versus the whirlwind of people who wanted his attention back in the day. They’re scared of what he’s going through.”

Moreno said the main thing for families affected by Alzheimer’s is that as the disease progresses, “there is still the ability for families and friends of the individual to maintain a connection to that person’s likes and dislikes. It’s important to treat them with dignity and respect.”

Even though she is pleased with the breakthrough, Rita Milch is realistic about the future.

“I’m aware of what David is able to do at this point, and what he was able to do when he was at his best,” she said. “We’re at a different point, and we have to accept that.”

In the final pages of his memoir, Milch addresses his plight in another true story.

“I still hear voices. I still tell stories. There are those in my head and another in my throat and others in my work. There is the voice in my wife’s head and the one in my children’s heads. The deepest gift I think an individual can experience is to accept himself as part of a larger living thing, and that’s what we are as a family. Shut the f— up, Dave. I still hear that voice too.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.