For Angelenos like my parents, Harry Belafonte had one title: King of the Greek

- Share via

Harry Belafonte kissed my mother once. I don’t believe she ever recovered.

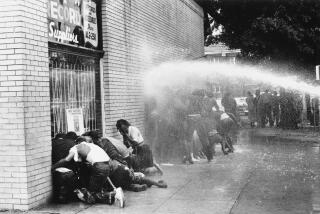

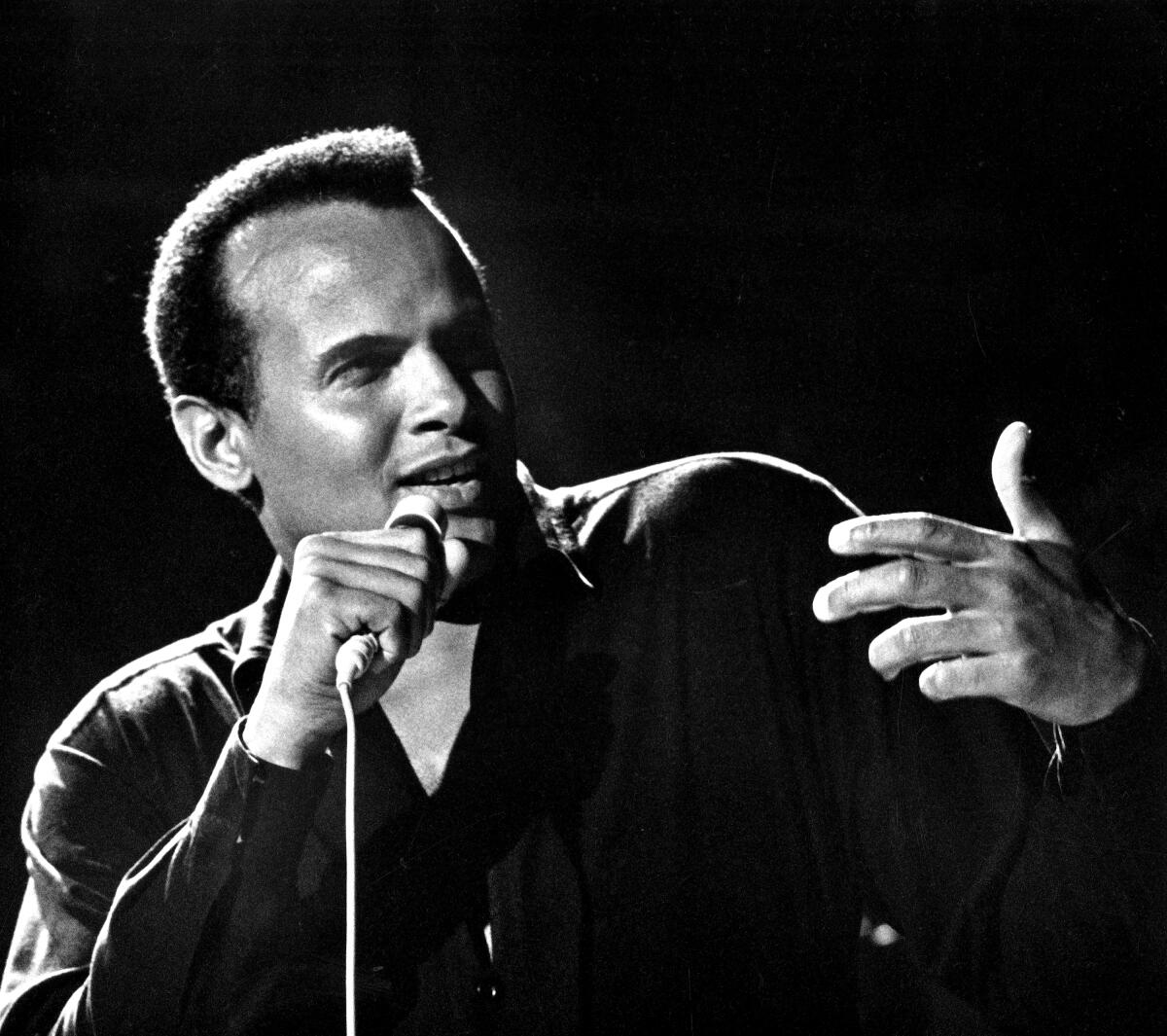

Belafonte, who died Tuesday in New York, is being celebrated as a versatile entertainer and dedicated civil rights activist. He traveled the globe to care for poorer people, and his later years were marked by his candid political perspective and outspokenness.

But for me and my family, he will always be known by one moniker above all: King of the Greek Theatre.

From the 1950s into the 1980s, Belafonte would perform at the outdoor theater nestled in the hills of Griffith Park. For his legions of Los Angeles fans, which included my parents, these appearances were more than a pleasant night of music and dance. They were must-see events, and always sold out. My mom and dad would never miss an opportunity to bask in the magic of his charisma and musical prowess.

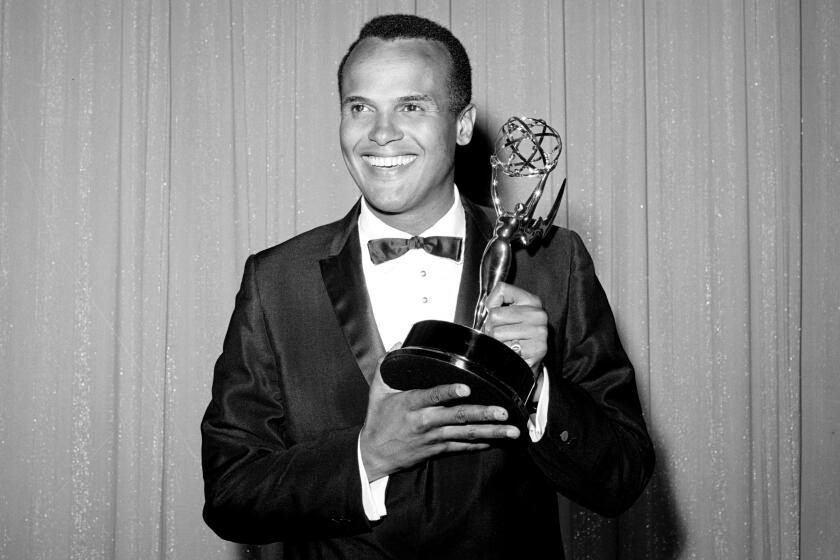

Singer, actor and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte dies at 96. He was the first Black man to win an Emmy and a Tony.

I can vividly recall when Belafonte would touch down at the Greek during summers of the 1960s and ’70s. I was too young to go, and my sister and I would have to be overseen by a babysitter or spend the evening with a neighbor. But I was very familiar with Belafonte’s music. It was the soundtrack of our house.

It seemed only a few days would pass before his “Calypso” or another of his albums would once again get spun on our hi-fi turntable. Naturally, “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” and “Man Smart (Woman Smarter)” were household favorites. My father would clench his fists and swing his arms, echoing the chorus of Belafonte’s declaration, “That’s right, de woman is, UH, smarter! That’s right! That’s right!” I thought it was a tribute to my mother.

They also loved his ballads like “Come Back Liza,” and his delivery was my early introduction to how powerful and lovely a singing voice could be.

But it was the Belafonte date nights at the Greek that really stood out. My parents would go out pretty often, but there was always an extra level of excitement before they went to see Belafonte. My mother would look especially pretty in her gorgeous dress, and my dad would dress up like he was going to church.

They would get home late, still bubbling with excitement. I would sit in bed as they described the concert in detail: Belafonte’s tireless energy, the audience’s endless cheers for more. He would tease them about encores: “Now you’re on my time.” He would give a shout-out to the “people in the trees” — fans who had not been able to secure tickets and had climbed into the high trees around the Greek to get a view of the stage.

My parents always brought home a program, and I would sit on the floor the next day gazing at the pictures of Belafonte in performance, with his family and doing charitable work around the world.

I was an adult when my parents saw Belafonte for the last time. A friend who lived in my apartment building was an usher at the Greek and managed to secure backstage passes for my parents. After the show, they went to the green room and watched patiently as Belafonte worked the room, greeting family and friends.

He eventually made his way to my parents. (“He came up to us!”) I’m not sure what their exact exchange was. But I do know that Belafonte kissed my mother, sending her into a near-swoon. He followed that gesture with a wink for my father.

Questlove, Spike Lee, Ava DuVernay, Ice Cube and Oprah Winfrey are among the celebrities who have posted about Harry Belafonte’s death.

I related that story to Belafonte, who recorded a live album at the Greek, when I interviewed him many years later in an office in Culver City. He and Taylor Branch were developing a TV version of Branch’s Pulitzer Prize-winning history of the civil rights movement, “Parting The Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63.”

By then, Belafonte’s performance days were long behind him. I was still struck by the power of his presence, his raspy voice, his commanding vision.

I was almost embarrassed but felt compelled to tell him how happy he had made my mother that particular night. He said nothing, but I thought I saw a gleam in his eye.

And he smiled.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.