What we learned from ‘Call Me Miss Cleo’ documentary about the infamous ’90s TV psychic

- Share via

Late-night TV viewers of a certain age were once well-acquainted with a certain TV psychic by the name of Miss Cleo, who made “call me now” her catchphrase.

The documentary “Call Me Miss Cleo,” which began streaming on HBO Max on Thursday, tries to decipher whether the woman was a gifted “voodoo priestess” who could converse with the other side or just a highly gifted master of deceit.

The mythology of the exuberant Miss Cleo, who rose to fame in the late 1990s as the animated spokeswoman for the ill-fated Psychic Readers Network, is at the heart of the film.

There are a lot of powers at work in the Gunpowder & Sky-produced doc — the realistic and the idealistic, the performative and the pure. The answers are there but they depend on who is being asked.

Stalwart of late-night commercials of the late ’90s and pop culture touchstone “Miss Cleo” died Tuesday after a battle with colon cancer, her lawyer confirmed to the Associated Press.

The filmmakers spoke with several people to try to unravel the mystery of Miss Cleo. There are friends who’ve experienced her readings and “gifts”; they are often the ones who let her off the hook. There are former clients and fellow phone psychics who’ve sensed her otherworldly connections but who fell victim to a hotline scheme. Former colleagues she allegedly scammed who vilify her. Experts and journalists trying to make sense of her. Government figures who participated in her downfall, and former partners who loved her.

And for laughs and some surprisingly spot-on analysis, actor Raven-Symoné and comedian Debra Wilson — who famously parodied Miss Cleo on the Disney Channel series “That’s So Raven” and MADtv, respectively — drop in to analyze her effect and legacy.

The consensus: The so-called Miss Cleo, who was born Youree Dell Harris in Los Angeles and who appropriated a Jamaican accent and fronted a lucrative empire, was a tragic figure who was taken advantage of and discarded just as quickly as she gained fame.

With those testimonials paired with a 2012 interview Harris gave for the 2014 documentary “Hotline,” “Call Me Miss Cleo” directors Jennifer Brea and Celia Aniskovich try to reveal “the truth behind the ever-enigmatic woman who took TV by storm, only to abruptly disappear from public consciousness.”

Here are some of those truths we learned:

Where ‘Miss Cleo’ came from

The self-proclaimed voodoo priestess died in 2016 after battling colon cancer, but it is her voice that guides the documentary, which doesn’t hold back on her over-the-top TV appearances for her pay-per-call service. But her early life and sketchy origins remain an enigma.

According to former colleagues at the Langston Hughes Theatre in Seattle, Harris was a playwright and performer who went by the name Ree Perris in the late 1990s. They said Miss Cleo was a character born out of a play called “For Women Only” that Harris was working on at the time for the troupe. Harris, who as far as they knew did not have a Jamaican accent, was set to play the character.

However, Harris told a different story in her “Hotline” interview: “I absolutely commune and chat with those on the other side — some call them dead, some call them spirits — but absolutely with the energy and vibrations with those that crossed over. ... more broader than a medium, for me, it’s a broader belief system.”

Former Langston Hughes colleagues said she was under contract at the theater and was paid a set amount. And that it was up to her to pay those she was involved with in the production. Apparently, she never did and disappeared. So her former colleagues were shocked when, years later, they saw the character in commercials on late-night TV.

In lawsuits filed against her and the Psychic Readers Network, it was revealed that Harris used a number of aliases, including Miss Cleo, Cleomili Harris and Youree Perris. The attorneys who obtained her birth certificate and deposed her said she kept her background vague.

Some of those interviewed for the documentary said she occasionally assumed other mystical identities too, which led them to believe she could have been experiencing potential mental illness. Others mentioned stories that she shared with them about an alleged sexual assault in her childhood.

How the Psychic Readers Network worked

Psychic hotlines were the anchor of the 1-900 number industry. Harris said her sister suggested she work for the nascent Psychic Readers Network, as it would be a source of income that would work with her schedule. Harris thought the commercials were silly but gave the hotline a shot in the late ‘90s.

“When they approached me about first being a spokesperson, my first initial response was, ‘I have a reputation to maintain,’” Harris said in the 2012 interview, arguing that she didn’t think the network took the practice seriously. But she also recognized that it was a business.

Infomercials--those half-hour commercials that resemble talk shows and other actual programs--continue to flood the airwaves.

According to the documentary, after she read her tarot cards on camera, the network allegedly got the greatest number of calls it had in its history. From there, she catapulted to fame, doing live readings with callers who could not believe how accurate she was.

Several people who worked for the network, which was shut down in the early 2000s after a Federal Trade Commission investigation, explained how it operated, admitting that they weren’t really psychics and that they needed work. They described working in an office, wearing headsets and being given a script to do “a reading.” And they were instructed, to the best of their ability, to keep the caller on the phone.

The first three minutes of the call were free, and in that time, the psychic had to collect the caller’s name and address to later be input into a system for mailers and other ads. After that, it was $4.99 a minute to continue the call. Most people called about money problems or love, and some called specifically to talk with Miss Cleo, which involved an elaborate ruse that ultimately kept callers on the phone for an even longer period of time.

“Miss Cleo people didn’t know a damn thing,” said Barbara Melit, a former PRN psychic who was the whistleblower who helped bring down the operation.

Hotlines “preyed on the souls that needed to be seen,” several former psychics said.

“The objective was not to help someone quickly, it was to drag it out,” added Harris.

Why she was so convincing

Harris’ dynamic energy and undeniable charisma certainly made her entertaining. And then there was that infamous, parody-ready accent.

“She was quick on the draw. She would take these sort of ordinary questions and launch into sort of very funny, very unexpected sort of spiels about whatever the topic at hand was,” said Bennett Madison, another former PRN phone psychic interviewed in the documentary. “I don’t really believe in, like, psychics or magic. But I do think that there are certain people who are good at being able to talk to someone and sort of understand who they are in an instinctive way and be able to give advice in a way that feels magical.”

“It was the best Insta[gram] Live you could’ve had in 1997. It was so good, so good,” Raven-Symoné said. “When I saw Miss Cleo, I did believe.”

Although Harris was regarded as comical by the Jamaican community, her appropriation of a Jamaican accent was part of the key to her success, because it gave her an air of “exoticism.”

“People were willing to spend more money” to speak with someone with an accent, said Ramone Walker, a PRN customer service representative who is Jamaican.

Andrea Nevins, a scholar and author of “The Caribbean Diaspora,” doubted Harris’ Jamaican heritage but gave credence to the psychic’s “renegotiated identity.”

“The idea that a Black body has these fantastical capabilities taps into sort of underlying understanding I think many of us have of Blackness as strangeness, really,” Nevins said. “So there were things about her race, I would say even her size and her gender, that helped to make it believable that she was associated with the fantastic.”

Stalwart of late-night commercials of the late ’90s and pop culture touchstone “Miss Cleo” died Tuesday after a battle with colon cancer, her lawyer confirmed to the Associated Press.

Thousands complained about the companies

Those familiar with the ubiquity of the late-night infomercials are likely also familiar with their disclaimers, which passed them off as “for entertainment only,” a catch-all phrase that did little to protect PRN.

In 2002, the FTC filed fraud and unfair telemarketing charges against Miss Cleo’s two Florida backers, Access Resource Services Inc. and Psychic Readers Network Inc. The companies were accused of defrauding customers after thousands of complaints were made by callers, former employees, parents of underage kids and people who didn’t call the hotline but received collection letters anyway.

Although the growing lawsuits predated Harris’ time at the network, they gained traction when attorney Dave Aronberg, the former Florida assistant attorney general who started the inquiry into PRN, included Miss Cleo as a named party in one investigation. He did so by obtaining a collection letter that had allegedly been signed “Cleo”; however, Harris claimed that it was a forgery and that she didn’t find out about the alleged signature on copies of the letter until she was deposed.

“I signed a really bad contract and brought in business, I’m getting a salary and no benefits. I’m an independent contractor,” she said. The attorneys being interviewed vouched for her because they saw how little she was paid after seeing her tax return.

“Her persona as Miss Cleo became an asset of the companies. They basically owned her image and her persona,” said Gerald Wald, an FTC receiver who brought the enforcement action against PRN.

Joyce Senfe was distraught when her husband walked out after 56 years of marriage.

Harris was later dropped from the lawsuit filed by Aronberg and became estranged from the company. The FTC went after PRN’s wealthy co-owners, Steven L. Feder and Peter Stolz, who declined to be interviewed for the documentary. Feder and Stolz agreed to pay $5 million in 2002 to settle charges that they had misled customers looking for an allegedly free glimpse into their future. The FTC also agreed to forgive an estimated $500 million in uncollected bills and send back uncashed checks to customers, who’d been charged an average of $60 for the supposedly free calls.

As the filmmakers point out, in settling with the FTC, Feder, Stolz and PRN “did not admit to violating any laws.” A network attorney also provided them with the following statement: “In any negotiations regarding compensation, Ms. Harris was represented by counsel and advisors that she independently retained. ... Other than portraying Miss Cleo’s character, Ms. Harris had no involvement in the affairs of PRN...”

She was an activist after the scandal

Friends, godsons, lovers and a former roommate offered illumination on what Harris was like after the investigation.

“How they portrayed Cleo destroyed her,” said her former makeup artist AnnDee Rucker. “They took her identity. They took her name. They sensationalized her. They villainized her. Of course, that had an effect on her. How could it not?”

She lived for several years as a recluse before Rucker and other friends tracked her down and encouraged her to start joining them for Sunday barbecues. She was the “cornerstone” of those events, her godson Dylan Rucker said.

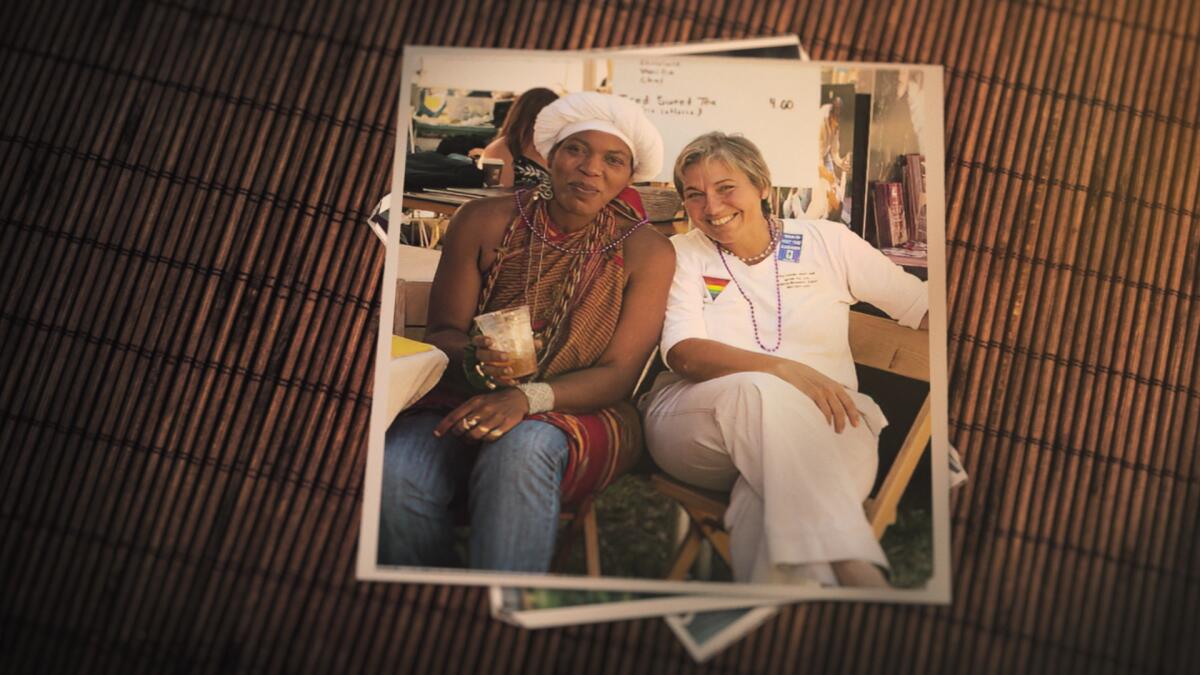

Harris became an activist in Florida, walking in Pride marches and working against antigay legislation; the coming out of another godson, Matt Rucker, became an impetus for her to come out as a lesbian in a 2006 Advocate article. Two of her former partners are also interviewed in the documentary.

“I sympathized with her over the years as well because I imagine that she moved through life with a certain level of heaviness that she couldn’t lift,” Wilson said. “If I can balance my recollections of her with acknowledging that there are ways in which she caused people pain, but also ways in which she brought people joy, then I’m OK with that.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.