A doctor told Oprah to ‘embrace hunger.’ How it changed her view of medicine forever

- Share via

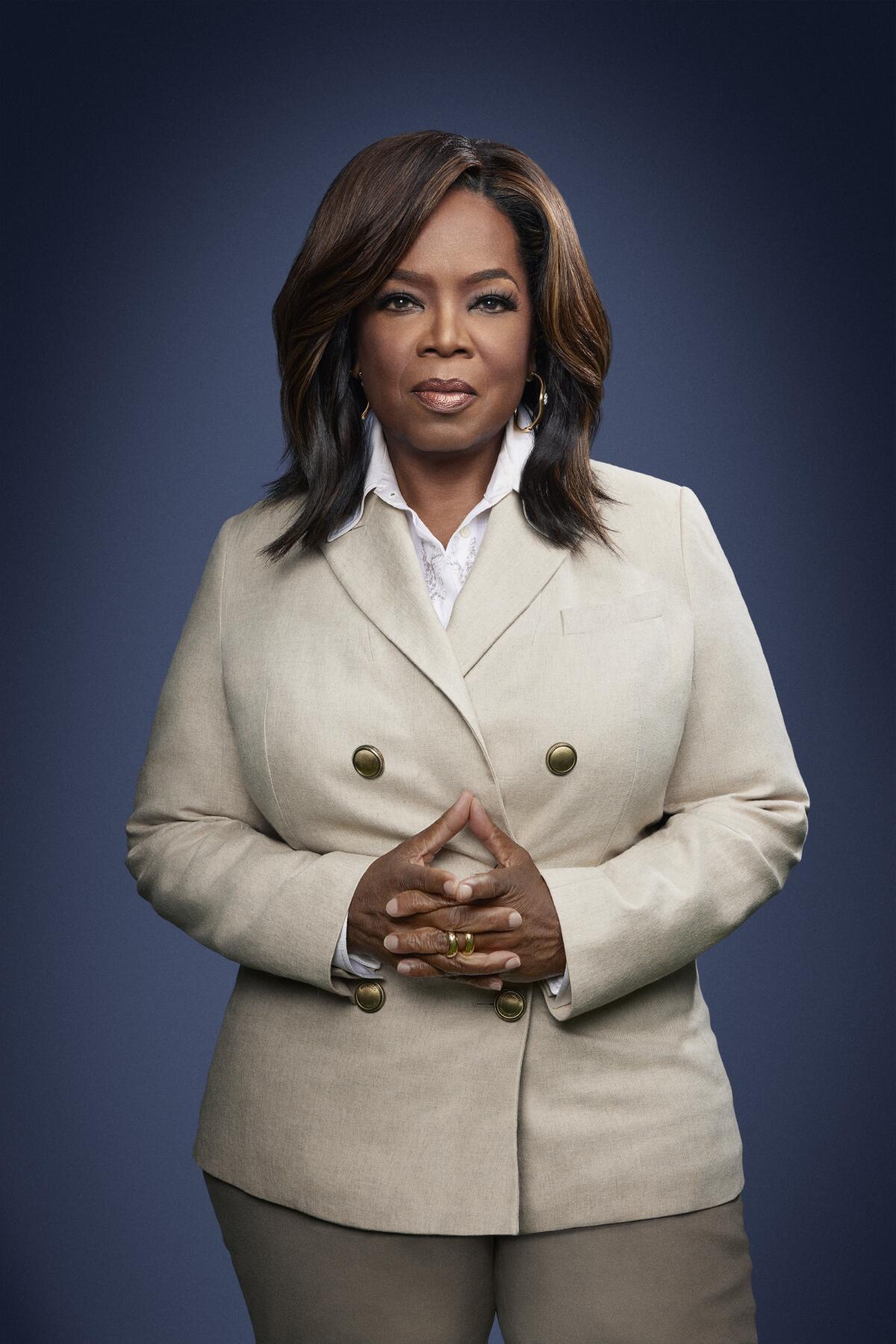

Oprah Winfrey will never forget first reading about Gary Fowler.

The television icon had been voraciously consuming news of COVID-19 and people who were losing jobs or dying from the deadly virus. But seeing Fowler’s face in USA Today, alongside the story of his experience going to multiple hospitals in Detroit to get help for COVID-19 before giving up, stayed with Winfrey. What’s haunted her most is that he sat in his favorite chair upon returning home and wrote, before dying, that he couldn’t breathe. She said she realized that that was something she would do too.

“I would want people to know at the last minute what I was feeling, what I was thinking, so I’d be probably journaling what those feelings were so that my family would have an idea of what exactly had happened,” Winfrey said.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Fowler’s story is what inspired her to executive produce “The Color of Care,” a documentary focused on how COVID-19 has exposed racial inequities in the health system. The film, from Smithsonian Channel and Winfrey’s Harpo Productions and directed by award-winning filmmaker Yance Ford, interviews families of color who lost loved ones to COVID-19 and the harrowing experiences their family members faced trying to access care before they died.

In addition to the film, there is also a campaign to reach future medical professionals, as well as communities that are affected and policymakers at all government levels to start thinking about solutions toward health equity.

Premiering Sunday on Smithsonian Channel, “The Color of Care” will also be available for free on Smithsonian Channel’s Facebook and YouTube until May 31. Winfrey spoke with The Times about how she’s navigated the pandemic, the biggest misconception she had about racial health disparities, and reflecting on how her privilege has shaped her healthcare experiences for better and for worse. The following has been edited for clarity and length.

Marissa Evans’ father began 2022 eating apple pie and feeling like it would be their family’s year. He died of COVID-19 before the end of January.

What was the story you read that made you want to sit down with me?

The story about your father [Gary Evans]. I thought you would be somebody who actually understood what it is we’re trying to talk about. Not just talk about, but what it is we’re trying to offer here. I see everything as an offering. Since the movie “Beloved” was so summarily rejected by the world, I learned to do all my work as an offering that either could be received or not be received. And you do the work and then you let go of any attachment to how it’s going to be received, or what people are going to say or whether or not they’re going to like it. You just do the work with the intention. I had read that article, at the time that it came out, because I just am one of those people who was reading all the COVID stories that I can get my hands on.

One of the reasons I read all of those stories is because I am appalled, I am stunned. I don’t recognize a country where you’ve lost nearly a million people and there hasn’t been some form of remembering that is significant. Not at the opening of a speech or mentioning in a State of the Union. I mean that there hasn’t been a communal gathering where there is acknowledgment that this has happened to us. Who are we that there is no acknowledgment, profoundly, in our society that we have lost our loved ones? And at times, we’re not even able to bury our dead. Who are we that we don’t recognize the significance of that acknowledgment?

How are you navigating that on a personal level, this collective grief you’re seeing right now?

I haven’t lost anybody in my family so I’ve been very fortunate. My dealing with it comes from hearing of other friends, and other people who have experienced it. My empathy and understanding of what that must be like to go through that is how I have been relating. I’ve been so careful with myself that my own friends make fun of me. I didn’t leave home for 322 days — literally did not leave the house. So it has not been for me personally a heavy burden to bear.

It was only the latter part of 2021 that it started to wear on me like, “OK, had enough of this.” But I still was feeling for all the people who were losing people and also people who couldn’t get appointments that they needed for just regular illnesses or checkups, because the hospitals are filled. I have lived this life of a “celebrity” since I was 19 years old, in Nashville, Tenn. And that’s only expanded over the years. But in Nashville [when] people first started recognizing me at the Kroger store, I noticed that things change for you when you are a person who is known. You get the doctor’s appointment. You don’t have to wait in line. You don’t have to deal with a lot of excess delays that other people have. And so I have lived this life of privilege and advantage, and then been exposed to the best of healthcare. I don’t normally get headaches, but if I get a headache I immediately think I have brain cancer. And so I’m now getting an MRI to get it checked out. And I can always get the MRI. Being exposed to what that kind of celebrity does when it comes to having access to what you need, I have a particularly strong empathy for people who can’t get it and don’t have it.

What has surprised you the most about living through the pandemic?

What has surprised me the most is how well I was able to adjust to the isolation and not being around other people. I remember one point [Gayle King] said, “Don’t you just miss being around other people?” I go, “Eh, not really.” And I think it’s because every day, I was in an audience of 350 people twice a day, so I’ve had shaking hands and autographs and selfies, and lots of attention, and exposure to being around a lot of people. I was able to be with myself in a way that I haven’t been able to for years, because usually, even if I take time off for myself, I’m thinking about what is the next thing to come.

Overall, I was able to adjust because I have the ability [and] really strong sense of being in this present moment and living this moment without having to worry about the next. You can do that when you don’t have to worry about where your next paycheck is coming from. I didn’t have to worry about, “Am I going to have rent? Am I going to be able to get food? Am I going to be able to keep the lights on and am I going to be able to take care of my children?”

And I make no apologies for it. Because I worked to earn it. Nobody gave it to me, I didn’t have a father that took over the business or a husband who left me money, or uncles who helped me. I feel completely responsible for having created the life that I have and also equally grateful and blessed for it. But I understand that it is a very blessed and privileged life that gives you access to healthcare, access to whatever you need, in a way that many people do not.

How do you think your access to healthcare would be different if you were not Oprah Winfrey?

It would be like everybody else’s. It would be like all the things I hear from people who are not me. It’s waiting in line, it’s being ignored, it’s people not taking you seriously, it’s telling people that, “Yes, I am in pain,” as well as people telling you it’s in your imagination.

Let me tell you, if ever you’re going to use your celebrity status, you want to use it when it comes to a medical emergency. Forget the restaurants, forget the free gifts. All the other attention you get for being a person who’s known in the world doesn’t even compare to what it means to have all eyes on you when something goes wrong. That is a real advantage. And it can also be a disadvantage.

There was a point back in 2007 where my heart was racing for an entire year. I had heart palpitations for an entire year and I went to five different doctors. And every doctor just gave me a different medication. Nobody ever checked my blood until I went to the Cleveland Clinic and they realized it wasn’t a heart problem. It was a thyroid problem that was causing the heart palpitations. So in that moment, the being a celebrity worked against me. I remember going back to one doctor who had actually given me an angiogram and I said, it wasn’t a heart problem, it was a thyroid problem. And she said, “What was I gonna do? You’re Oprah Winfrey, and I wasn’t going to have you die on me without having done everything I thought I could do.”

Vaccination rates are up, but there’s fear Black and Latino men will continue waiting until they almost die from COVID-19 or watch people they know die before getting vaccinated.

When this doctor said, “I’m not going to have Oprah Winfrey die on me,” what was going through your mind?

I actually thought, “How irresponsible [of her] not to have just given me a blood test.” And I also thought, for the first time, “I can see now that when you show up and you’re a known person, although everybody seems excited to see you, they’re also nervous, because they’ve got to also cover themselves.” I keep that in mind anytime I’m going into a new doctor.

I have no qualms about asking all the questions. I was, in the beginning, like your father, believing doctors know more than the rest of us and you don’t want to waste a doctor’s time. After I discovered it was a thyroid problem, I went to a doctor who specialized in thyroids. I’m very much on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” and he knows exactly who I am but he goes, “Well, young lady, you are just going to have to embrace hunger, otherwise you’re going to gain a lot a lot of weight.” I did multiple shows [about] people speaking up to their doctors and being able to feel like you are an equal partner with them in securing the best health treatment for yourself. That you need them and they need you to help them understand what’s actually going on with you. That’s the way I look at it now, but in the beginning, I was also intimidated by doctors, like your father.

But that experience with the thyroid taught me that you need multiple opinions and you need somebody advocating for you. I don’t care who you are. I would never go into a hospital by myself. Even as a person of note, with a name, I would never go into a hospital by myself. I would always have somebody go with me who’s advocating for me. That’s a hard, hard road to navigate by yourself, especially if you’re ill.

Before this film, what was the biggest misconception you had about racial health disparities?

I think my biggest misconception was that it was about health insurance, that it was about having access financially, and if you didn’t have the money, then you couldn’t get the care that you needed. What COVID laid bare is that inequities in so many other areas of your life also contribute to the major disparity when it comes to healthcare.

There will be people who watch the film and say racial health disparities don’t exist, or that racism in general is not an issue in healthcare. How are you preparing yourself for those viewer reactions?

It is an offering for the people who can receive it. So I’m not here to argue with the people who cannot. I am here to do what we really wanted to do with this film is to let people know that it’s more than just one film, it’s a moment to ignite a vital cultural conversation around this public health crisis. So it’s not just about the film. For me, it’s the Color of Care impact campaign, it’s a way to move this conversation forward, and actually champion some changes to hopefully eliminate racial disparities in the delivery of U.S. healthcare.

Loving a Black man in America often means your time with him will always seem short-lived.

Knowing what you know now, after hearing from all these families and health experts, and reading so much coverage about COVID-19, how would you grade the United States’ response to the pandemic?

It would serve no purpose for me to try to give the United States a grade on how the response has been. I am interested in as many people knowing about health disparities, and also about the Color of Care and what we’ve tried to do to make it accessible for people to see. But as I was saying earlier, what saddens me most is there hasn’t been an acknowledgment about what we’ve been through. So to grade us on how well we did or didn’t do, or what should have been done, actually, I don’t think at this point serves a purpose. I’m just trying to move forward.

I just heard today that masks are being taken off the planes and people cheering. Well, that will not be me. I personally think it’s too soon to be removing masks from planes. But that’s what people choose to do. And if I were on a commercial plane, I would be one of the people who would still be wearing my mask. And I would be one of the people still wearing my masks in an enclosed building with people who I didn’t know if they were or were not vaccinated. But that is just me. And I certainly accept that there are other people who disagree. I’m OK with that as long as I can wear mine. And so people who look at me cross-eyed when I do, OK.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.