Now at Netflix, ‘Powerpuff Girls’ creator savors freedom: ‘Wait. We can do this now?’

- Share via

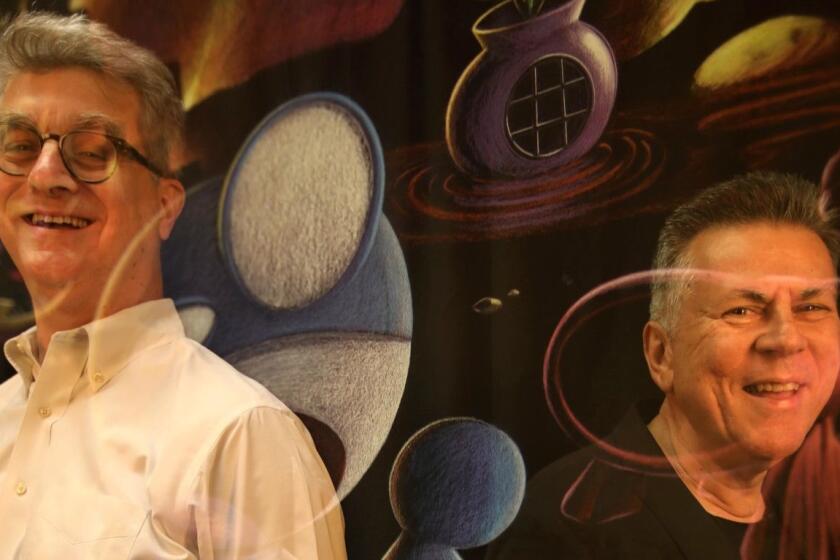

Animator Craig McCracken, who gave the world “The Powerpuff Girls,” “Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends” and “Wander Over Yonder,” has an exhilarating new cartoon series, “Kid Cosmic,” premiering Tuesday on Netflix. Set on a thinly populated stretch of American desert — there’s a diner, a motel, a junkyard — it concerns a kid, called only the Kid (Jack Fisher), who comes across some powerful stones dropped by an alien on the lam. While they confer powers on the bearer, they also bring in their wake a host of unfriendly ETs trying to get their hands, claws, etc. on them.

Haphazardly, an unlikely team of heroes comes together: The Kid, Jo (Amanda C. Miller), a waitress; Rosa, (Lily Rose Silver), a toddler; Papa G (Keith Ferguson), the Kid’s grandfather; and Tuna Sandwich (Fred Tatasciore), a cat. Tom Kenny, the narrator and Mayor on “Powerpuff,” plays Chuck, an extraterrestrial enemy kept close.

Along with friend and sometime collaborator Genndy Tartakovsky (“Dexter’s Laboratory”), McCracken was at the forefront of a second wave of innovative, creator-driven television animation, whose first wave began in the 1990s with the likes of Ralph Bakshi’s “Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures” and John Kricfalusi’s “The Ren & Stimpy Show.” With “The Powerpuff Girls,” which ran from 1998 to 2005 on Cartoon Network under McCracken’s watch (it was rebooted in 2016 without him), he hit a sweet spot that combined action, humor, historical allusiveness and multigenerational appeal; “Kid Cosmic” strikes those same notes in a completely different way, with a more naturalistic, highly detailed look and a serialized approach to storytelling. Its first season has as much to do with a live-action miniseries like “Stranger Things” as it does with anything we’ve seen in cartoon form.

For a decade, veteran TV executive Fred Seibert’s studio pitched the idea for an edgy animated story inspired by a 1989 Japanese video game.

“Kid Cosmic” seems to straddle the past and the present — there are cellphones, but also landlines, videocassettes, 45s, cathode ray TV.

The main idea is that the kid grew up in this junkyard with his grandpa, and a lot of that stuff he has is just stuff his grandpa had around; he’s kind of a poor kid, and he’s made the best of a bad situation. His grandpa collects junk and so there’s old video games, old comics, old records, and Kid has just kind of consumed all this media from different eras. Even his bike is made out of parts of other bikes. And also I like that design aesthetic; I like antiques and junk and I’m a big “American Pickers” fan. My grandparents were collectors and my mom and all my uncles were collectors — I’ve been growing up with that stuff my whole life.

There is a hand-drawn look to the series, a kind of sketchbook aesthetic, with detail many cartoons would leave out.

The drawing style came from the fact that the show conceptually is grounded in reality — these aren’t cartoon characters, per se, they’re real people. So I started looking at other forms of cartooning that had that nice balance between iconic, caricature cartoon characters, but also placed in the real world. And I gravitated toward Hank Ketcham’s Dennis the Menace, but more specifically Hergé’s Tintin. I grew up with Tintin and I love the fact [that] those were definitely cartoon characters but felt like real people; and the environments those stories would inhabit were really tactile and believable. Because the show is about regular people thrust into this extreme situation who aren’t really good at what they’re doing, I wanted the show visually to have a human, homemade component; I wanted you to see drawings on the screen — like, people made this. This isn’t like slick, CG, super-polished.

Are there themes that tie your series together, do you think?

I definitely do. “Kid Cosmic” is an amalgam of a lot of things I’ve done. It’s got superheroes like “Powerpuff,” it’s got science fiction like “Wander Over Yonder,” it’s an odd assemblage of misfit characters like “Foster’s” — it’s sort of all the the things I like in one thing. There are also character archetypes: My father passed away when I was 7, so I was raised by a single mother, and that’s kind of an ongoing theme that’s not really been conscious but it’s been in all my shows. “The Powerpuff Girls” only had Professor, Mac [in “Foster’s”] only had his mom; the Kid has his grandpa. And also the dynamic between Frankie and Mac and Kid and Jo is very similar to my relationship with my older sister; my sister’s 11 years older than me, and she’s the one who introduced me to the Beatles and “Star Wars” and Monty Python. And so the idea of being a young kid growing up with a cool older girl is just part of me growing up — that thread runs through my shows as well.

Goodness seems to me a recurring theme in your work.

That’s how I see the world. I like positivity, I like kindness, I like that hippie-dippy type of a guy. I didn’t want to make a show about violence, and I didn’t want to make a show about if somebody’s different from you and you label them a bad guy, just beat them up and you win. The theme of the show was “Heroes help, not hurt.” Even Papa G says, “Evil’s just a cry from a heart that’s hurting.” I believe those things. I believe that there are reasons people become evil — there’s always something broken deep down — and that you can try to help people. And that’s what being a hero’s really all about. It’s not about just being the cool fighter. And I wanted the Kid to learn that. And also Kid has experienced some loss in his life. He wants to stop bad things from happening because bad things did happen to him. But it’s sort of accepting, like, “Well, that’s a part of life.” There’s suffering and it’s how you cope with it and grow through it. I wanted to do a different type of kids’ show that wasn’t just about “Hey, what neat powers.” I always say it’s about the people, not the powers.

Brian Henson, chairman of the Jim Henson Co., talks about growing up around Muppets and the role only 30 to 50 people in America are capable of performing.

Rewatching “Wander Over Yonder,” and looking at certain scenes in “Kid Cosmic,” I was reminded of Chaplin and Keaton and old comedy shorts that were less about story than accomplishing a single difficult task.

Well, I’m a huge, huge, huge Jacques Tati fan. I love those movies — just watching character behavior, not a lot of dialogue, just visual storytelling. [In] “Wander Over Yonder” we did one episode called “The Breakfast” and it was just Wander and [his nemesis] Hater making breakfast and how these two characters would deal with that in a different way. I like watching characters go about their lives without a lot of plot, a lot of talking. “Wander” to me was basically Bugs Bunny cartoons: It was just about the spirit of love and the spirit of hate-chasing each other around the galaxy. “Looney Tunes” meets “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.”

How does the longer format change what you’re able to do creatively?

It allows us to let stuff unfold, which is really nice. When you’re limited to 11 minutes or 22 minutes to tell a complete story you just have to move through as fast as you can and hit the most important story beats. But when we’re telling this long-form serialized story, it lets the show breathe. I was really happy that in the first episode I didn’t have to quickly have Kid run in and say, “I love comic books and superheroes and I found these rings from space.” I could just show his environment, show pictures of his toys, show pictures of his comics, let him wake up and play superhero. I like that we could make one episode with two characters and introduce the other characters episode by episode. I love that in the third episode we literally spend 45 seconds with the cat just crossing the road. It’s a joke you couldn’t normally do in an 11-minute [episode], but with a Netflix show, you totally can. And because they’re not locked to a broadcast network time frame, they can be whatever length — some were 25 minutes, one was 16. It’s whatever you need to tell the story.

Does Netflix operate like a studio, or do you feel more independent?

It feels like being independent. People who have worked there are like, “This feels like being at Cal Arts and you’re making student films but they’re giving you a lot of money to make your student film.” And you can kind of do it the way you want to, because they don’t really have a brand agenda like, “We make these types of shows for this demographic.” It’s just, like, “We want to work with content creators we like who we think will make good things, and we’re going to give them the freedom to do their work.” I haven’t felt like I had that much total creative freedom since the early days at Cartoon Network, when they just kind of trusted us to make those shows.

Animation was still kind of cultish when you got into it. Now it’s everywhere.

I love it. Back when I started, the one great period in cartoon animation was the golden age of the 1930s and ‘40s, “Looney Tunes.” I grew up with that; and there were a few glimmers in the ‘60s, with Jay Ward and early Hanna-Barbera stuff. But we were always looking to the past to find the rich source material to be inspired by. But now there are so many good shows [that] have been made and so many incredible creators who’ve been making shows since the ‘90s that are really different and really diverse and are pushing the art form forward. Part of “Kid Cosmic” came from the fact that Rebecca [Sugar] was able to do some serialization with “Steven Universe,” Alex Hirsch was able to do serialization with “Gravity Falls” and Pen [Ward] a little bit on “Adventure Time.” That, to me, was like, “Wait. We can do this now? We can tell longer stories? Networks are OK with that?”

In Netflix’s “The Midnight Gospel,” premiering Monday, “Adventure Time” creator Pendleton Ward partners with Duncan Trussell to explore the cosmos.

Given that cartoons are often produced in multiple cities, does working in the pandemic seem less of a change than it might have?

It actually opened it up a lot more. Most of my character design team is in Canada; we’re hiring storyboard artists in Mexico. Because we’re able to meet and talk virtually, it’s opened up where we can reach out to hire talent; they don’t have to be centralized in Los Angeles anymore. The one thing we do miss, though, when we would get episodes or work prints in, we’d all get together as a crew and watch together, and you could just see if it was working when you’re in a room with everyone laughing and responding, talking afterwards. That aspect we’ve really lost. And [McCracken’s wife, “DC Super Hero Girls” animator] Lauren [Faust] is working on a project as well for Netflix, and she said story meetings are harder to do over Zoom because you’re not in that room kind of jamming together, playing catch, talking on top of each other — you’re losing that human dynamic. But it’s worked out. We’ve been able to continue producing a show without too much disruption.

You have a 4-year-old daughter. Has fatherhood changed the way you work?

Definitely. It’s grounded me a lot more, it’s made me think deeper about story and not just, “Hey, let’s be funny.” It’s a whole different perception of the world, and it changes your priorities a lot. I love making cartoons, but it’s no longer the most important thing in my life. To start my own family finally, it means the world to me, really.

She’s a little storyteller — she’ll take any object and turn it into a character. She found some toy earrings and immediately ascribed personalities to them. She can just pick anything up and make stories out of it, especially objects that are similar and one’s bigger and one’s smaller, because that’s immediately like a mom and a baby. We call her The Director because she’s always telling us where to go and what to do.

She just discovered “The Powerpuff Girls.” We weren’t going to show her really early on, because it’s a little violent. But we have some statues of them in our house and she just wanted to know who they were, so I played her the main title, and she watched it like 20 times and I could see the wheels turning in her head. She went, “They’re kids, but they’re superheroes ... but they’re kids!” And I’m like, “Oh good, it’s working.”

‘Kid Cosmic’

Where: Netflix

When: Any time

Rating: TV-Y7 (may be unsuitable for children under the age of 7)

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.