Commentary: The myth of Tigermania has lasted 25 years. HBO’s new doc takes a swing at it

- Share via

If you’re a golf fan, at least, you’ve seen it before.

Tiger Woods at age 2, swinging a golf club for Bob Hope on “The Mike Douglas Show.” At 18, punctuating his go-ahead birdie in the 1994 U.S. Amateur with that now-iconic fist pump. At 20, announcing his decision to turn professional — and presaging Nike’s advertising slogan — with the phrase “Hello world.” At 21, bringing Augusta National to its knees and the culture to a standstill with his first victory at the Masters.

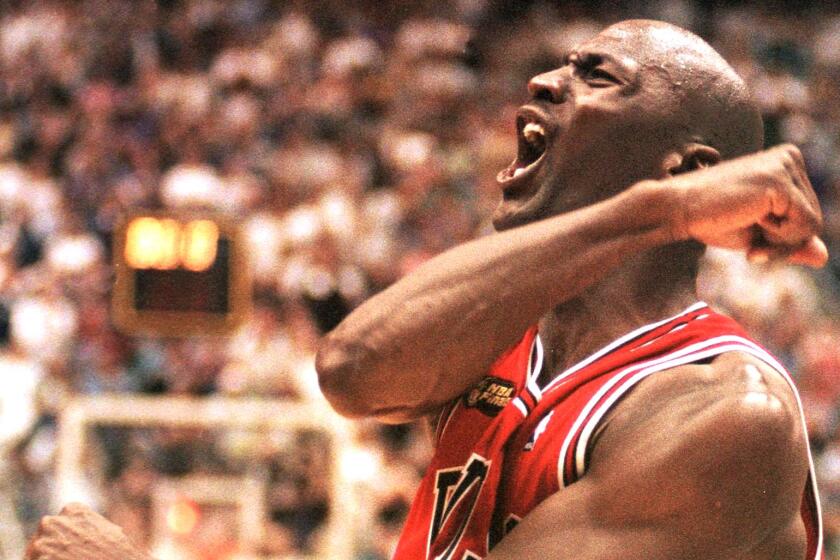

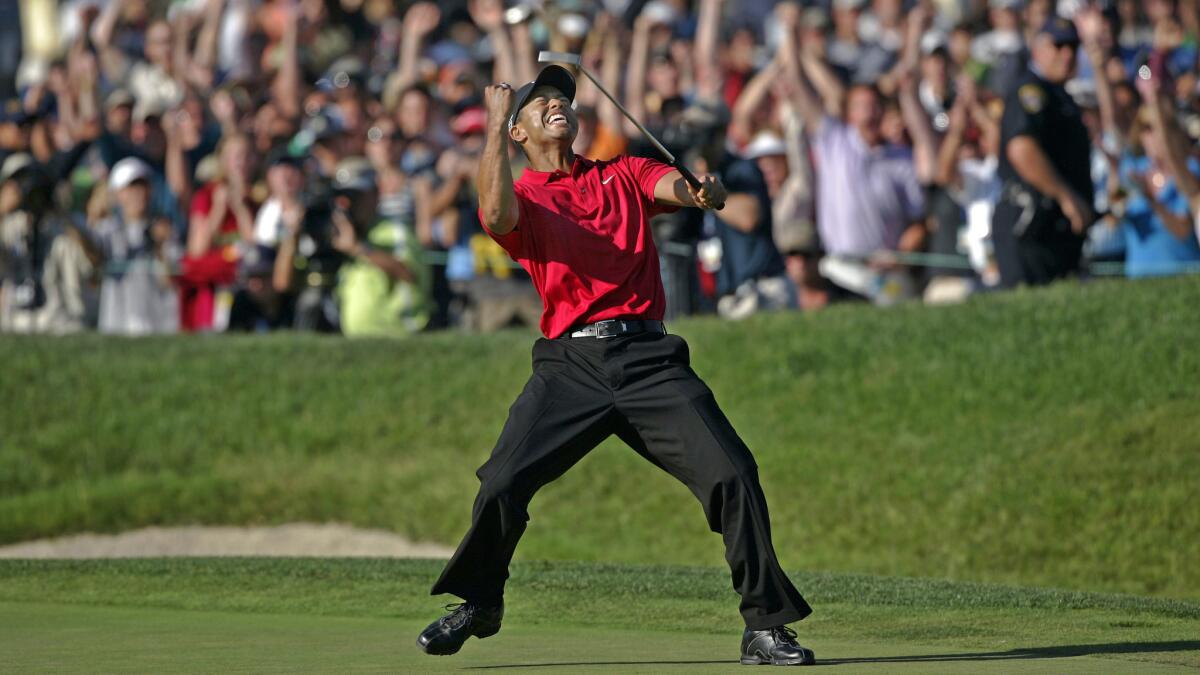

The uppercut, the swoosh, the primal roar: This is the iconography of “Tigermania,” the craze that overtook the sporting world the late 1990s and early 2000s, and which lends HBO’s two-part docuseries “Tiger,” premiering Sunday, its opening sequence. Against footage of his son’s teeming galleries, Earl Woods, speaking at the banquet honoring the top collegiate golfer of 1996, offers the promise that will shape expectations of Tiger for years to come: “He will transcend this game and bring to the world a humanitarianism which has never been known before. The world will be a better place to live in by virtue of his existence and his presence.”

Now 45, after multiple injuries, a tabloid sex scandal involving Rachel Uchitel and numerous other women and a DUI arrest that left his reputation and his ranking tarnished, it’s clear that Woods — despite his barnstorming comeback win at the 2019 Masters — is not the transformational figure his father promised. In truth, as I reported for Deadspin in the summer of 2014, he never was: As measured by both overall participation in golf and the number of Black, Latino and Asian golfers at the recreational level, Woods’ impact on the game has been negligible. “What we really mean by the term ‘Tigermania,’” I wrote at the time, citing TV networks, the sport’s governing bodies and its elite players as the main beneficiaries, “is not an influx of golfers but an infusion of money.”

ESPN and Netflix’s docuseries “The Last Dance,” about Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls, is ambitious sports storytelling at a moment we’re aching for it.

“Tiger,” based on Jeff Benedict and Armen Keteyian’s 2018 book, “Tiger Woods,” and co-directed by Matthew Heineman and Matthew Hamachek, at once draws on and dismantles the familiar imagery and the standard narratives that constitute Tiger lore. The result, less biographical portrait than psychological case study, stops at all the stations of the cross: Earl’s counsel, encouraged by his own florid anecdotes, to “let the legend grow”; Nike’s search for “the next Michael Jordan”; the obsessive pursuit of golfing perfection and awe-inspiring dominance, culminating in the 2000-2001 Tiger Slam.

The difference here, even in the portion of the docuseries focused on Woods’ rise to stardom, is the more forthright skepticism of what writer Charles Pierce calls “the gospel of Tiger Woods” — and particularly of Earl, its “original evangelist,” who died in 2006.

Before the elder Woods’ opening monologue ends, for instance, we’ll see his son being handcuffed and having his mugshot taken in connection with his 2017 reckless driving arrest.Tiger’s kindergarten teacher is recruited to call Earl “a definite SOB.” Sports Illustrated’s Gary Smith, whose 1996 profile of Tiger first introduced the “Chosen One” mythos to the wider public, is juxtaposed with a clip of the golfer as an adolescent, comparing himself to Michael Jordan. And Woods’ first girlfriend, Dina Parr, describes a “shrine” of Tiger’s plaques, awards and framed clippings in the family home, her words accompanied by an awkward photograph of the teenage Woods posing before it.

“Tiger’s” reading of Earl and wife Kultida Woods as the ultimate helicopter parents, instilling in their son the grandiose self-image and white-knuckle insistence on absolute control that will ultimately bring him low, isn’t terribly sophisticated.

Still less so — especially in light of criticisms levied at the project for its lack of behind-the-scenes diversity — is the series’ handling of race, which becomes, if not an afterthought, a subsidiary issue, playing second fiddle to the more salacious stories of parking-lot trysts and Vegas madams. Where ESPN and the Undefeated’s recent “Tiger Woods: America’s Son” foregrounds Woods’ racial identity and situates it within the history of racial exclusion and barrier-breaking Black professionals in golf, the lion’s share of “Tiger’s” analysis comes in a single sequence, with reference to slurs overheard at the Masters, Woods’ preference for “Cablinasian” to describe his identity, a Wanda Sykes joke and an interview with Bryant Gumbel.

The Times TV team selects the 15 shows we’ll be watching when they premiere or return in 2021.

At minimum, it’s a missed opportunity to marshal the series’ evidence toward an argument larger than the space between Tiger’s ears. Earl Woods might have begun the myth of Tigermania, but as Smith argues at one point, it was “white America patting itself on the back” that turned the subject of glossy magazine profiles into a bona fide phenomenon. And it was a certain stratum of white America — as represented by TV networks, governing bodies and elite players — that profited most handsomely from Tigermania, and from the stratospheric Nielsen ratings, lucrative rights agreements, skyrocketing purses and multiyear endorsement deals that came with it.

Perhaps the most powerful moment in “Tiger,” then, is also its most unsettling, and the one that made me pause over my own reaction to the greatest golfer of his generation. As I wrote for Golf Magazine 10 years after his 2008 U.S. Open win, when it seemed he might never win another, there has been no more electrifying player to watch, at least in my lifetime, than Tiger Woods — and yet it’s apparent that the sense of near-cosmic significance attached to his very real on-course prowess originated, at least in part, as a marketing scheme.

“Do we want to play the race card?” Nike advertising director Jim Riswold recalls asking of the 57-second “Hello World” spot — “There are still courses in the U.S. I am still not allowed to play because of the color of my skin” — that accompanied Woods’ first, $40-million contract with the company. The answer was resounding, and like Earl Woods himself, it established a set of expectations for and about Tiger with which he, golf and culture are still reckoning, 25 years later.

Riswold answers his own question: “F— yeah.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.