Commentary: Forget Trump’s daily briefings. Watch these coronavirus messengers instead

- Share via

We have become a nation of castaways, combing the bandwidth from a hundred million islands fearfully, hopefully for news.

Key to this new way of living is the press conference — local, state, national, airing, streaming, reporters in attendance or calling in. (And sometimes no reporters at all.) Purely as information, you could learn it all from the newspaper — subscribe today! — but we come not just for the facts but for the performance. We come for the reassuring voice, the confident body posture, the air, if we’re lucky in our chain of leaders, of competence. We come even for the look of distress that says Someone Cares. And, oddly, we are as close to the mayor, the governor, the president in our current predicament as we are to nearly all our friends and relations — just a screen away.

One might imagine that, in a time when anyone in the world might upload a video to a place where anyone in the world might see it, the act of appearing on camera would have lost some of its meaning. But an aura of consequence, of urgency, of event still surrounds these meetings of important people with the press and the public beyond — not least, of course, because they concern a virus that might kill any of us, and has in short order changed the way we live.

They amplify what was already a tradition. Woodrow Wilson held the first presidential press conference in 1913 — the White House Correspondents’ Association formed a year later — and they have been a feature of every administration since, though held in different settings at different intervals. (There are no rules.) Early pressers, out of public view, could be informal, even collaborative, not completely on-the-record affairs. Dwight D. Eisenhower was the first to put one on television, in 1955, though it was shot on film and edited; JFK was the first to go live and unedited on TV, days after his inauguration in 1961. The present occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. has been all over the television, for hours, in recent weeks.

At a moment in which viewers are eager for facts about the coronavirus outbreak, nightly news programs and other venerable formats are delivering.

A conference may state a case, and might be called on to defend it. It may deliver a hard truth, or spin an inconvenient one. Lawyers on courtroom steps reinforce the narrative they’ve been unspooling inside; movie stars shine their light upon the world. When the news is soft (“Tell us about your new picture”), some puffery is expected; in serious matters, it is good to be, or at least sound, authentically honest. Broadcast live, a conference tells us something extra about character, something a transcript can’t express. I look at my mayor, Eric Garcetti, and governor, Gavin Newsom, a little differently, and certainly more charitably, having watched them at work, moderating a crisis. It was the Beatles’ music that first charmed American youth, back in 1964, but their press conferences won over the parents. (“What do you think of Beethoven?” Ringo: “Great. Especially his poems.”)

This rapidly evolving (yet somehow slow-rolling) emergency demands frequent communication. Trump’s TV briefings — lengthenings, I guess we could call them — are pivotal, certainly, to understanding the moment, if not always in the way he intends, and most valuable when he steps aside to let the experts talk.

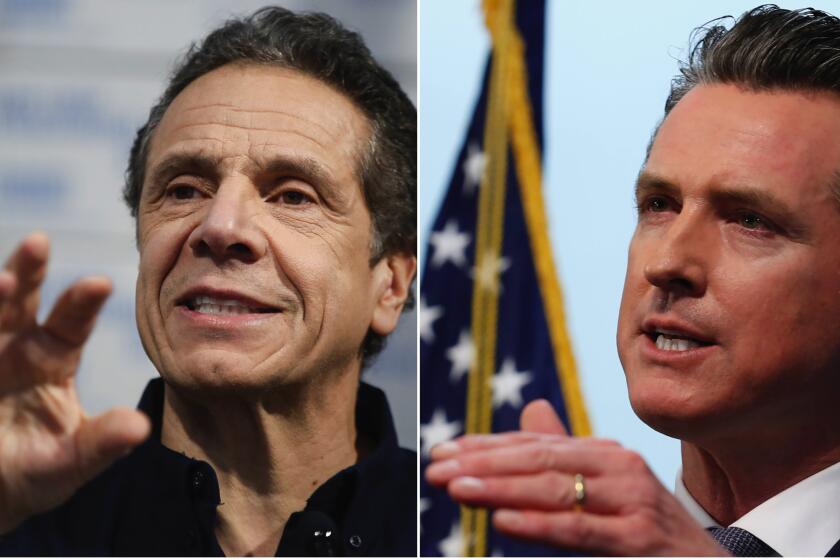

But to get a clearer picture of what’s up in America — a picture of things getting done — I recommend a visit to the country’s governors and mayors, who are closer to the front line and whose meetings with the press and public are generally available on YouTube or a dedicated government website. Many play close variations on a theme: The officials appear, flanked by flags, with doctors and administrators on hand, sometimes joined by a general, as the Army Corps of Engineers arrives in one theater of viral war after another to turn stadiums and hotels and convention centers into field hospitals. Many employ ASL interpreters for deaf viewers — though New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo does not, nor does the White House. Especially at the city level, the briefings may be more informal. (I’m looking at you, Fort Lee, N.J., Mayor Mark Sokolich.)

Cuomo’s daily press conferences have attracted national interest, because New York is farther into the crisis than elsewhere and because Cuomo himself projects an easygoing, empathetic sort of tough love, and sounds like Al Pacino, not overacting. I don’t know much about Cuomo, apart from his illustrious parentage, but I note that many constituents not otherwise inclined to like him seem to now. (According to a CNN report, Cuomo’s briefings are “mandatory viewing” in the West Wing, as well.)

Even from 3,000 miles away, listening to Cuomo can reduce stress, not because he sugarcoats but because he shoots straight: “Calibrate yourself and your expectations so you’re not disappointed every morning you get up.” But he also gets personal, usually to a broader point, talking about reforming family tradition in a remotely connecting world, chiding his kid brother — broadcast journalist Chris Cuomo, currently quarantined with the coronavirus — for having spent time with their mother.

At the Jacob Javits Center, made over into a hospital, he addressed the Army Corps of Engineers, in a sort of off-the-cuff echo of the St. Crispin’s Day speech from “Henry V”: “This is a moment that is going to change this nation … and 10 years from now you’ll be talking about today to your children or your grandchildren, and you will shed a tear because you will remember the lives lost and you’ll remember the faces and the names, and you’ll remember how hard we worked and we still lost loved ones. … But you will also be proud. …. When other people played it safe, you had the courage to show up.”

Closer to where I shelter in place there is Gov. Newsom, who is tall and youthful and gets up close to the camera, projecting a kind of Northern California easiness that falls somewhere between friendly politician and local television host; in another life, and easier time, I can see him hosting a children’s show, with puppets. He likes to call California a “nation state,” which, for a native, reinforces the comforting sense of a bulwark against whatever madness might reign elsewhere.

“I completely reject this notion that we are destined to any particular fate; it’s decisions, not conditions, that determine our future,” he said recently.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, who conducts his briefings from behind a lectern in the middle distance in a paneled room — it’s like a 12th-row view — comes across as a kind of inspirational technocrat: “We have not seen the darkest days, but we will march forward, and we’ll march forward together.” Neither governor nor mayor is political in his broadcasts, except in the sense that avoiding politics may itself bring tangible rewards, might open doors that otherwise would stay closed. (Though Trump has attacked Newsom in the past, he now regularly praises his work on the pandemic.)

In the age of coronavirus, Govs. Andrew Cuomo and Gavin Newsom have become the nation’s truth-tellers and consolers in chief.

Trump! Until Tuesday, he seemed barely to have reckoned the human cost of the pandemic, and certainly not its enormity. Through whatever combination of intention, ignorance or mental indiscipline, Trump is a habitual stater of untruths and half-truths, and this vague fog of fancy and fact — hyperbolic, sloppy, hypnotically repetitious — keeps his rhetoric slippery. There is a lot of noise surrounding his signal, and he can swallow great tracts of time without actually saying much. Asked in late February if he thought the virus would spread, his reply was literally all over the place. “I don’t think it’s inevitable. It probably will. It possibly will. It could be at a very small level or it could be at a larger level. Whatever happens, we’re totally prepared.”

Or perhaps not.

Indeed, the question has been raised among media critics and news outlets whether it is worth covering Trump’s briefings live and unfiltered, given that they contain much misinformation, some of which may lead viewers to dangerous action, or inaction. It’s a big country, and some part of it will obviously find in these briefings exactly the psychological balm it needs — notwithstanding the name-calling, blame-shifting, aspersion-casting, self-congratulations, history-rewriting, conspiracy-theorizing, kowtow-receiving and campaigning. Indeed, the president has boasted on Twitter of his “Bachelor finale, Monday Night Football type numbers,” numbers he apparently interprets entirely as a token of support, rather than, say, driven by fear of sickness, death and the collapse of civilization.

There are numbers and there are numbers. At the task force’s Tuesday briefing, that fatalities would be enormous even if things go well seemed to have finally sunk in, as perhaps had the idea that nothing Trump could say would stop it — that this isn’t the flu, nor a hoax cooked up by a Democratic cabal. For whatever reason — whether images he’d seen from Elmhurst Hospital in his old neighborhood in Queens or that, as has been reported, internal polling showed that voters preferred stricter measures in slowing the pandemic — Trump appeared, if not chastened, at least quieted. He left off the usual sniping and for a moment got out of the way of his advisors.

Then came Wednesday’s briefing. “Did you know I was No. 1 on Facebook?” said Trump. “I just found out I’m No. 1 on Facebook.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.