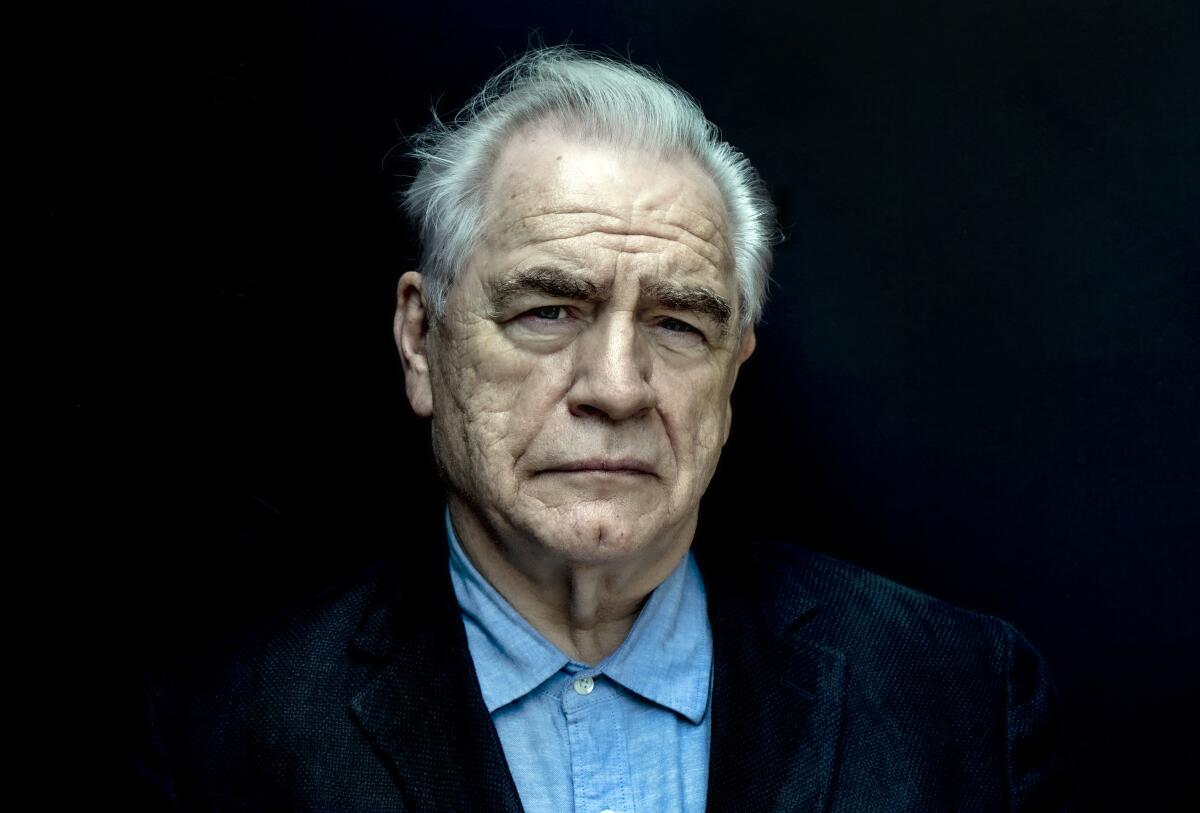

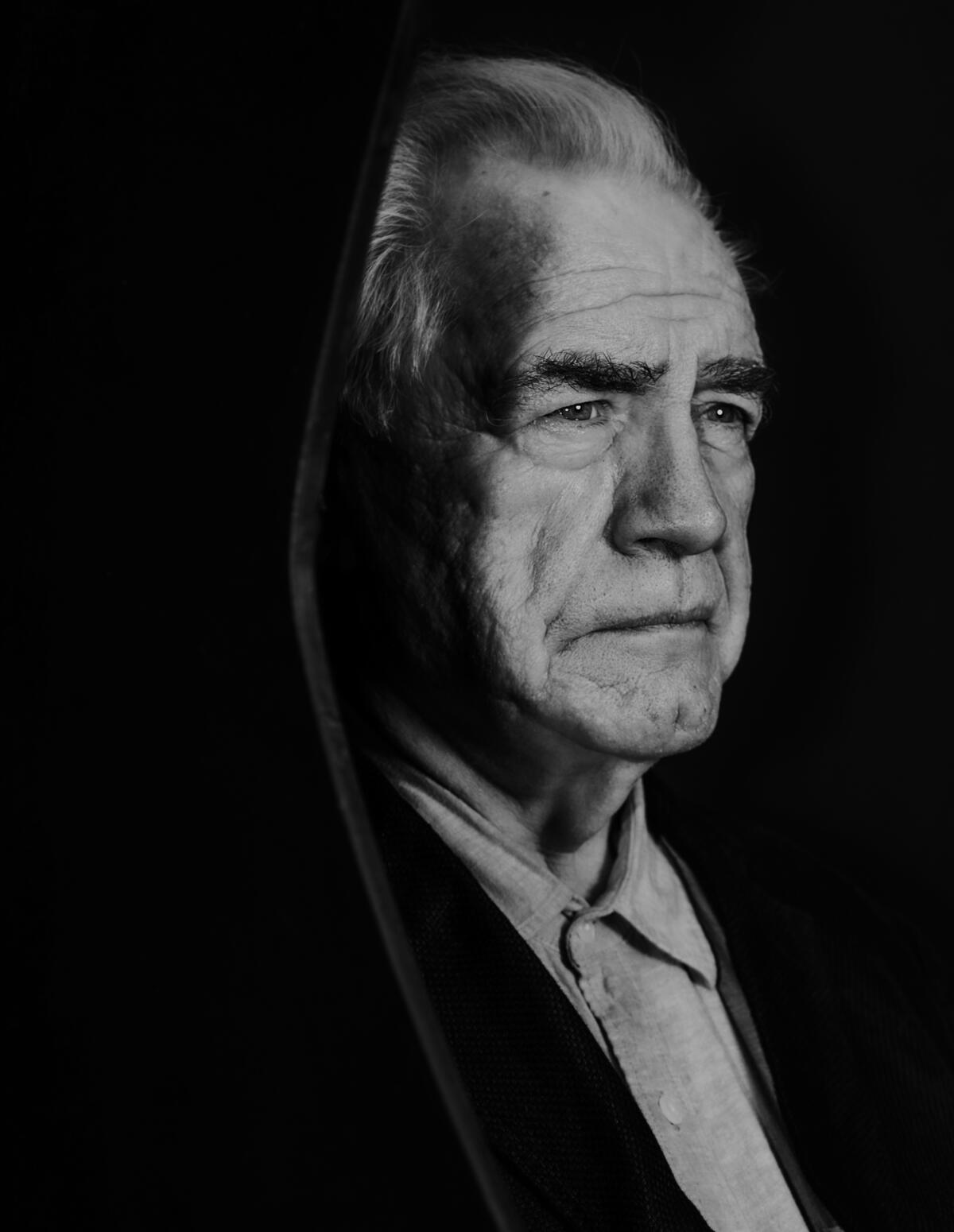

Brian Cox knows why ‘Succession’ reminds you of the Trumps: ‘It’s about entitlement’

- Share via

NEW YORK — “I could tell you,” says Brian Cox, taking a sip of his iced matcha latte, “but then I’d have to kill you.”

A few hours before going onstage to play Lyndon B. Johnson in “The Great Society,” the actor is in his dressing room at the Vivian Beaumont theater, coolly deflecting speculation about who will be the “blood sacrifice” — the person to take the fall for a corporate scandal threatening to bring down a media dynasty — in the much-anticipated season finale of “Succession,” which is set to air two days after our interview.

It’s exactly the sort of thing his character in the HBO drama, a Rupert Murdoch-esque conservative mogul named Logan Roy, would say — but might actually mean.

The bluntly profane patriarch — last seen smirking elusively in the closing shot of the season — has made the 73-year-old character actor into an unlikely social media darling, the subject of myriad GIFs and memes. Cox, who is active in the Scottish National Party and describes himself as a socialist, doesn’t have much in common with Logan politically, but the character has been shaped in his image: Both men are from working-class Catholic families in Dundee, Scotland, and lost parents at a young age.

Days after wrapping production of “Succession” in Croatia, Cox returned to New York to begin three weeks of breakneck preparation for “The Great Society,” trading his gentle burr for a Texan drawl he practices by listening to LBJ’s White House tapes. A follow-up to the Tony-winning “All the Way,” which starred Bryan Cranston as Johnson, Robert Schenkkan’s nearly three-hour play charts the president’s final years in office as the war in Vietnam escalates and undermines his progressive domestic legacy. Next month, Cox will appear in the film “The Etruscan Smile” as a cantankerous, terminally ill Scotsman who bonds with his infant grandson.

Over the course of a long and winding conversation, Cox holds forth about the Scottish Enlightenment, Dundee’s jute-weaving tradition and the Opium Wars: “I don’t think we acknowledge history nearly enough. In order to know where we’re going, we need to know where we’ve come from.”

.

Lyndon Johnson has intrigued many actors, biographers and dramatists. Why does he interest you?

I always had a predilection towards him ‘cause he always reminded me of my dad. He looks like my father. Clearly, he’s a Celt — you could see that in his face. [He points at LBJ bust on the vanity behind him.] When he turned into the bad boy, I was always a bit sad about that. The thing that impresses me most about LBJ is the fact he was a teacher. If you think about what’s happening to children on the border now — well, those kids were his students. He had a great empathy for them and empathy for the poor.

You would have been a young man when LBJ was president. Do you recall having impressions of him at the time?

I was at drama school with a lot of American actors. Their fate was that then when you left, you would get conscripted. A few of them had nervous breakdowns. The actor Michael Moriarty had a breakdown, and a lot of it was to do with what was going on in his life, but also the pressure of that was hovering over you.

What excited you about this particular interpretation?

It’s a language play. And that’s why it’s very exhausting, because I can’t pause, I can’t take a breath, I have to keep it going. It’s very dense and it has to be played with incredible dexterity. Otherwise it becomes a tome, and it isn’t. Robert has these incredibly long sentences, but they have to be taken at such a lick to get through to the object at the end of the sentence. And that’s what makes the play dynamic.

Were you anxious at all about taking on a role that had been played before to great acclaim by Bryan Cranston?

No, not really. I didn’t know about it to be honest. I’ve been so busy. I had kind of vague memories that Bryan Cranston had played LBJ, but it wasn’t at the front of my conscious thought. A friend of mine, Michael Gambon, played him somewhere on down the line [in the HBO film “Path to War”].

The rap on you is that you played a lot of bad guys in your career.

I have. I remember quite a long time ago when I was playing a lot of bad guys [such as Hannibal Lecktor in the film “Manhunter” and Hermann Göring in the miniseries “Nuremberg”], I’d go, “Why me? Why do I always get to play the dregs of the Earth?” And then I turned [it] on its head and I said, “Well, it’s actually a privilege to be given the opportunity to examine human nature at its most basic.” But there was a point where I thought, “I’d just love to play a good guy.”

Is there one character that was the hardest for you to grasp?

The toughest one and the most challenging one was in a film called “L.I.E.” I played Big John, a man who was a pederast. People kept saying, “You don’t want to do that.” He had developed this relationship with this boy who he was initially physically attracted to, but then it became something else. And I found that fascinating. It was tough because [writer-director Michael Cuesta] had to get this balance between this predator and at the same time this carer. It was astonishing, difficult ... challenging — and rightly so, you know?

Where do you think Logan Roy fits in this spectrum? His brother argues he’s as bad as Hitler.

I don’t think he is. He’s a sort of mystery wrapped up in an enigma. There are doors that he’s closed throughout his life and he’s not allowing them to open. But the thing that’s absolutely important to understand — it was the thing that I was doubting until I talked to the genius Jesse Armstrong [“Succession’s” creator-showrunner] — I said, “Does he love his children?” And he said, “He most certainly loves his children. He just doesn’t express it very well.”

My father died when I was 8. My mother was institutionalized. I really had no parents after the age of about 9. That’s why I personally found fatherhood really rather impossible ‘cause there’s no template for me. I’ve never known how to behave.

I don’t do all of that Method [acting] crap. You know? But I think that’s Logan’s problem — that he was never looked after, that he was an abandoned child. There’s a history of deprivation at a very profound level. I get it.

Is it hard for you at all coming from a working-class background to exist in this world of excess and greed?

Yes. The artistic responsibility is to see it as it is, which is a morality tale. It’s about entitlement and about the time we live in. You look at Ivanka, you look at Kushner, and the fact that they are in positions which they have never been elected to. There’s nothing democratic about where they’ve come from. And I think that there’s a lot of that going on in the world. People [once] understood that you have to earn the right to do certain things. People like Trump have evaporated that because of their own sense of righteousness. And his sense of righteousness clearly comes from abuse. His father bullied him and his brother died of alcoholism. All of these things have a knock-on effect, you know? That’s why history is important. We are victims of our history.

How was it for you to go home for the “Dundee” episode?

I go back a lot. But going back this time, under these kinds of strictures, was weird. There I am, playing one of the richest men on Earth. My elderly sister came down. And she’s quite frail now. She said [he switches to a higher-pitched, thickly accented voice], “It’s all very grand Brian, isn’t it?” I said, “Yeah, that’s what I’m playing.” She said, “Who’da thunk it, eh?”

He’s probably one of the grandest characters you’ve gotten to play.

Oh, yeah. And now’s he’s become this iconic figure. It’s really extraordinary what’s happened to Logan. I always knew the potential of the role. And of course they’ve now run with that potential brilliantly in this season. The most daring was the “boar on the floor” episode [“Hunting”]. When I got that episode, I said [to writer Tony Roche], “I don’t know if I can do this. This is really something.” He said, “No, go on. You’ll love it.” We know Logan is demonic, it’s always there, but it’s locked in the cupboard. You open it up and it’s, “Oh no, shut that door.”

The other shocking moment was when he hits Roman.

But that’s what the Scottish do — a backhander. I’ve seen that in real life, you know? Fathers giving their kids a backhander like that.

In “The Etruscan Smile,” you play a different kind of Scotsman. Your character, who is terminally ill, bonds unexpectedly with his infant grandson. Did you relate to his journey? You had your two youngest kids relatively late in life.

My eldest son’s nearly 50 now. I remember I had to tell him, ‘cause I don’t have any grandchildren and he was 32, I believe. So I had to tell him that my wife was expecting a baby and he said, “Oh, I have to think about this.” I said, “OK.” We were in Ouarzazate [Morocco]. So I’m standing in my hotel room looking up as he’s walking round the desert in Ouarzazate thinking about it. And then he comes back after about 10 minutes, and he says, “Well, didn’t you take any precautions?” And I said, “It was meant.” And then I said, “You know, I wouldn’t mind grandchildren. So I decided to make my own.”

Does playing someone who is dying make you think about aging?

Absolutely. The great thing about work is that work sustains you. Doing this play, I had three weeks to prepare. I haven’t done this kind of theater for going on 30 years. When I played all the great classical roles like Lear and Titus Andronicus, I was in my late 30s, early 40s. Supposedly that was my prime. I’m not sure if that was the case. I think my prime is yet to come. But I called on that younger self. I just sat down and meditated and I thought, “Well, I did it before.” And my younger self said, “Well, I think we’ll probably find there’s still a lot of muscle memory there.” And he assured me that it would be OK. I’m a Gemini, so I have a lot of these conversations with myself.

People are very obsessed with how you, as Logan, say “[Expletive] off.”

It’s so weird. People have been telling people to [expletive] off for years now. But it’s also very Scottish. Nobody swears better than the Scots. The Irish are pretty good. But the Scots really do it, especially if it’s mean. But it’s bizarre. It’s caught something with people. That’s the exciting thing about Logan, his language can be so basic. My favorite quote from Logan is when he says, “My favorite Shakespearean quote is ‘Take the [expletive] money.’”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.