‘Enemy of the People’ is the 19th century drama that still resonates with our pandemic-scarred society

- Share via

“An Enemy of the People,” Henrik Ibsen’s 1882 play about a doctor-turned-whistle-blower, is never out of season. But it would be challenging to find a 19th century drama that speaks as directly to our pandemic-scarred society as this one.

Dr. Anthony Fauci could vouch for the accuracy of Ibsen’s play, which depicts the way politicians and business leaders close ranks when a public health emergency threatens their pecuniary interests.

Dr. Stockmann, the crusading doctor who refuses to compromise on scientific principles, is designated “an enemy of the people” for his defiant opposition to a pressure campaign to suppress information he’s uncovered on the contaminated water supply feeding the town’s mineral baths, the economic lifeblood of the community.

In the spa town of Southern Norway, where “An Enemy of the People” is set, money trumps medical safety. Mayor Peter Stockmann, the doctor’s brother, is concerned immediately with how much this problem will cost — cost being measured strictly in monetary terms. Illness, suffering and death have no place on his ledger sheet.

No wonder Theater of War Productions, the company led by Bryan Doerries that built a reputation through public conversations around readings of dramatic classics grappling with social discord, trauma and injustice, has turned its sights to Ibsen.

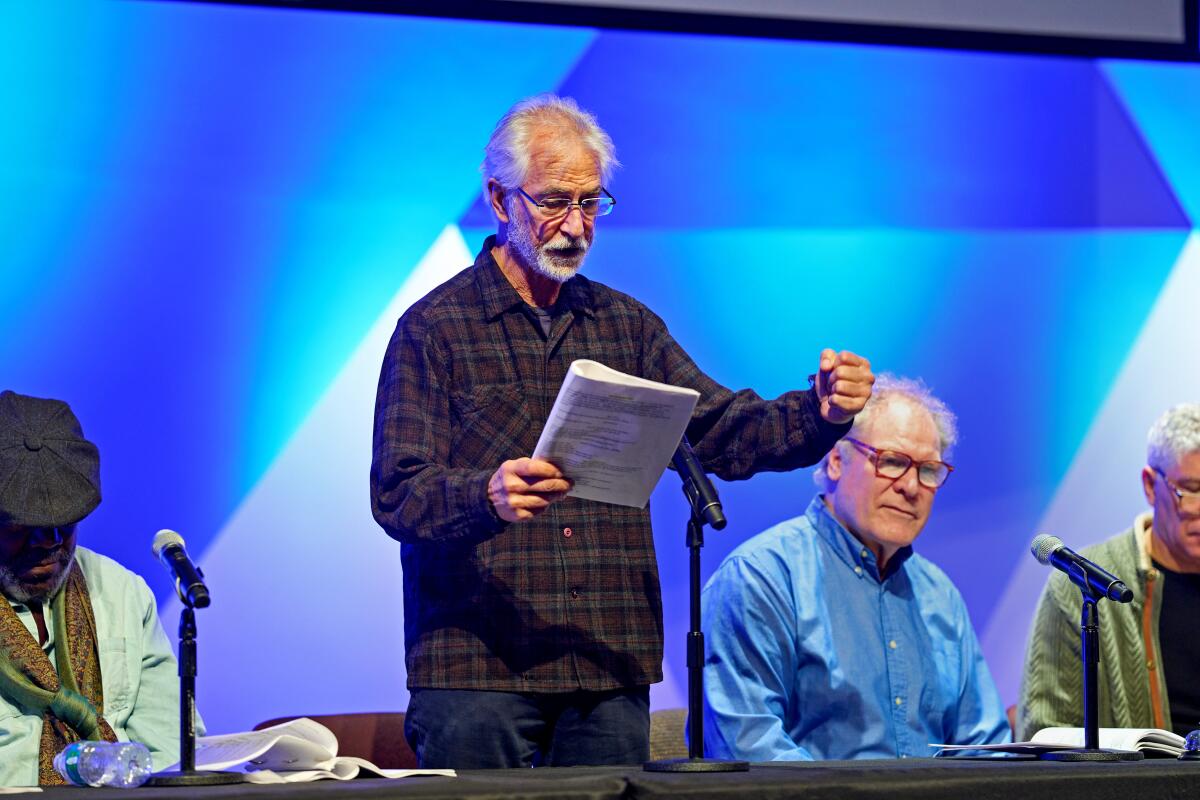

On separate nights in February, Doerries brought a cast that included David Strathairn and Jay O. Sanders to the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center and to the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., to hear and discuss two acts of Doerries’ new version of “An Enemy of the People.” Discussion panels, which included public health leaders, engaged the play from a post-pandemic point of view.

Playwright Amy Herzog has written her own adaptation of “An Enemy of the People,” which opens March 18 on Broadway. The production, directed by Sam Gold, has been garnering a good deal of attention, not all of it to do with Ibsen’s political perspicacity. Jeremy Strong of “Succession” takes on the role of Dr. Stockmann, and Michael Imperioli of “The Sopranos” and Season 2 of “The White Lotus” plays the mayor — casting that lends an HBO frisson to the fraternal standoff.

Ibsen wrote “An Enemy of the People” a few years after Nora slammed the door on her oppressive marriage in “A Doll’s House” and ushered in modern drama. The playwright was still reeling from the more recent controversy he stoked with “Ghosts,” a play that turned a young man’s case of hereditary syphilis into a metaphor for society languishing under the weight of dead beliefs, calcified ideologies and suffocating moral codes.

Ibsen’s frustration with petty-minded popular opinion was boiling over when he sat down to write “An Enemy of the People.” He fueled his anger at the response to “Ghosts” into his new play, the story of a doctor who, like Ibsen, is pilloried for telling difficult truths.

Guided by data and prodded by ethical duty, Dr. Stockmann sounds the alarm after documenting that the water feeding the town’s No. 1 tourist spot — its mineral baths — is poisoned with industrial runoff. At first, he is assured of crucial support from Hovstad, the editor of the town’s newspaper, and Aslaksen, a printer and chairman of the Home Owners Council. Hovstad fancies himself a revolutionary; Aslaksen is a cautious incrementalist. Yet both reveal their true bourgeois colors when the economic heat is turned up.

The mayor uses all the tools at his disposal to thwart the release of his brother’s damning report. Unable to debunk the science, he attacks Dr. Stockmann’s character and rallies the business community for battle.

Increasingly embittered as one by one, his supporters fall by the wayside, Dr. Stockmann snarls back at his opposition with anti-democratic rhetoric. How, he asks, can the majority be trusted when narrow self-interest is allowed to run roughshod over the commonweal?

The central conflict of “An Enemy of the People” resonates in manifold ways today — from the water crisis in Flint, Mich., to the political demonization of public health experts during the COVID-19 pandemic to the MAGA Republican effort to undermine truth itself. But unlike “A Doll’s House” and “Hedda Gabler,” which are never out of the repertory for long, “An Enemy of the People” has gathered dust on the academic sidelines.

Often classified among Ibsen’s sociological dramas, this debate play may seem less psychologically layered than the Norwegian playwright’s best-loved works. Yet one of the foremost champions of “An Enemy of the People” was none other than Konstantin Stanislavski, whose portrayal of Dr. Stockmann at a time of revolutionary upheaval in Russia informed his understanding of how an actor intuitively creates a role even in a politically charged drama.

“An Enemy of the People” came at the end of a group of “issue” plays that began with “Pillars of Society” and included “A Doll’s House” and “Ghosts.” It’s the work that perhaps more than any other identified Ibsen as a rebel playwright with a cause. Yet there’s more to the play than its blistering social critique.

Henry James once commented on the “absence of humor” in Ibsen’s playwriting. (“There is nothing very droll in the world, I think, to Dr. Ibsen,” James wrote in a commentary that is otherwise exceptionally astute.) Yet for all its grave concerns, “An Enemy of the People” has quite a lot of comedy and satire embedded in its structure.

The work has been called Ibsen’s most Shavian play, and indeed, George Bernard Shaw, a staunch defender of Ibsen’s trailblazing art, has endorsed the drama’s subtle political argument. For Shaw, Ibsen is daring to point out a glaring weakness of democracy — an attachment to the status quo that can manifest as a resistance to progress. The play isn’t suggesting autocracy or anarchy as a replacement, but it does expose the lie that, in Shaw’s words, “the great liberal-minded majority” is always the best arbiter of new ideas and paradigms.

Yet, as critic Eric Bentley reminds us, “one must always look for the idea behind the idea” in Ibsen’s work. “An Enemy of the People” complicates its own argument as human foibles and blind spots reveal themselves on both sides of the debate.

Dr. Stockmann is clearly identified with Ibsen as an intrepid truth-teller, but one of the playwright’s central tenets is that a writer must “sit in judgment on oneself.” As with many idealistic reformers, Dr. Stockmann seems to like humanity more in theory than in messier reality.

The heroic, standalone qualities of Ibsen’s protagonist earn our respect but not our reflexive loyalty. In the twisting, unschematic development of the play’s ideas, it is suggested that a new generation — Dr. Stockmann’s daughter, an esteemed teacher, and Capt. Horster, a seaman who puts more stock in courageous action than self-aggrandizing rhetoric — may have to prepare the way for society’s painstaking evolution. The streak of narcissism in Dr. Stockmann limits the reach of his brilliance. He too must grow if his community is to move out of darkness, a point that dawns on him in the play’s final act.

In a conversation on Zoom, Gold and Herzog, who are married yet have maintained until now separate careers, explained that it wasn’t simply the obvious political interest that drew them to “An Enemy of the People.” Gold found a copy of the play among Herzog’s Ibsen materials when she was working on Jamie Lloyd’s 2023 Broadway production of “A Doll’s House” led by Jessica Chastain. Lightning struck with a casting epiphany.

“Of course, you look at the play and you think, ‘Well, that’s really on the money for what’s going on in the world,’” Gold said. “But more than that, when I looked at it, I immediately thought of Jeremy Strong, who is an old friend of ours and who I just really saw as Thomas Stockmann.”

Dr. Stockmann is a deceptively tricky character, in some ways as difficult to pin down as Kendall Roy, Strong’s role on “Succession.” Courageous in his commitment to scientific truth, he espouses opinions that can strike us as elitist and illiberal today. Herzog, who has another play on Broadway this spring (“Mary Jane,” starring Rachel McAdams), described these views “as pretty troubling and problematic.”

She also pointed out some of Dr. Stockmann’s disturbing personal characteristics. “He’s self-centered, and he takes the women in his life for granted,” she said. “His journey is a hero’s journey, and he certainly withstands a lot of pressure and does some very admirable things over the course of the play. But I don’t think he’s a totally straightforward hero.”

In her boldest departure from the original, Herzog has cut the character of Dr. Stockmann’s wife, a change that alters the doctor’s “psychological starting point.” He is now, she said, coming out of grief. Her adaptation also moves away from what she called the play’s harsher satire that “laughs at other people’s expense” to the kind of “comedy that comes from the recognition of people struggling imperfectly to relate to each other.”

In his own adaptation, Doerries — who was influenced by Arthur Miller’s stark and brooding version of the play — toned down some of Dr. Stockmann’s more jarring scientific beliefs, which flirt with the now discredited theory of eugenics. He sees Ibsen’s drama, as he explained in a phone conversation, in direct line with Greek tragedy, though with one important caveat.

“In Greek tragedy, everyone believes they’re right and pursues it,” he said. “These are stories about people who learn too late, usually by milliseconds, and in that time destroy themselves and generations to come. But here, everyone, except for Stockmann, who isn’t socially aware of how he’s perceived, seems to know they’re wrong and are pursuing it anyway with full consciousness.”

The different reactions to Dr. Stockmann at the two Theater of War Productions readings I attended online were instructive. The first group, at Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center, was understandably sympathetic to the situation of a public health advocate hitting a brick wall of resistance. They related the character’s increasing frustration to their own experience of pandemic burnout.

The second group at the National Academy of Sciences was a good deal more critical of Ibsen’s protagonist. Dr. Francis S. Collins, who served as director of the National Institutes of Health from 2009 to 2021, said that whenever he attends a film or a play, he always looks to find a hero but was unable to find one here.

“Dr. Stockmann is on the side of truth and science. He’s trying to make a good public health action and be environmentally sensitive and all those things that we would admire. So he started out in my mind as a fairly admirable character. But then the wheels started to come off the bus. Gradually, he moved from standing up for something that was going to be good for the health of his town to attacking the government and the leaders, calling them all kinds of names — of being self-involved, corrupt and incompetent. And then he moved on from that to attack pretty much everybody except his own crowd, which, as Hovstad says, might be considered aristocrat and revolutionary.”

Both audience groups were alert to the reality that “An Enemy of the People “ isn’t simply about who’s right and who’s wrong. Dr. Stockmann, after all, has the receipts. The stickier question, as public health workers know all too well, has to do with persuasion and messaging. Dr. Stockmann is cruelly branded an “enemy of the people.” That’s a lie, but he still must learn how to be a true friend to his compatriots without compromising his principles and ideals.

Gold said that in grappling with Dr. Stockmann’s nature, both he and Herzog were influenced by Naomi Klein’s recent book “Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World,” which explores the way extreme polarization distorts our identities in the digital era. In a resonant pre-internet illustration of this thesis, the mayor’s infuriating hypocrisy, cloaked in communal concern and democratic pieties, drives Dr. Stockmann, a man of reason, into an irrational frenzy.

We’re still catching up to Ibsen’s ideas, but the challenge of staging his plays in the 21st century is stylistic. The sprawling, meticulously worked out plotting can seem ploddingly old-fashioned. (Hence, the appeal of adaptations.) European auteurs, such as Thomas Ostermeier and Ivo van Hove, have had success burning away what impatient modern audiences might consider novelistic padding. Their productions of “Hedda Gabler” went straight for the dialectical fire.

Ibsen’s theatrical vision is too valuable to lose, which is why it’s exciting that Broadway is reviving the play through the innovative talents of Gold, a director working in the tradition of Ostermeier and Van Hove, and Herzog, a shape-shifting playwright with a singular downtown sensibility. And it’s fortunate that Theater of War Productions — which will be offering presentations in April of “An Enemy of the People’’ in Knox County, Ohio, a part of the state that voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump in the last presidential election — is taking the play on the road for a much-needed national conversation. (Tickets, both virtual and in person, are free and available at theaterofwar.com.)

In an age of shortened attention spans and knee-jerk reactions, Ibsen’s play invites us to do something that might strike us as paradoxical — rethink our certainties without relinquishing our moral compass.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.