- Share via

Over the last two decades, Walt Disney Concert Hall has blazed cultural trails like no place else. We can rightfully talk about the L.A. Philharmonic before and after Frank Gehry built it a hypnotizing new home. We can divide downtown L.A. into pre- and post-Disney. We can go so far as to distinguish orchestral life, not only in L.A. but everywhere, in the same way.

Gehry turns 95 on Wednesday, and the L.A. Phil season, which began with a gala led by Gustavo Dudamel celebrating the architect, has, in ongoing tributes to the hall and in just doing its thing for these nearly five months, readily revealed, week after week, all that Disney is. And, alas, all that Disney inexcusably isn’t. At least not yet. But the best of Disney first.

Building Disney was a long, laborious, contentious, financially dicey process, one for which we’ve never had a full or convincing account. I’ve never gotten straight answers about who did what to whom and when.

In 1987, Ernest Fleischmann, at the time the transformative head of the L.A. Phil, enticed Lillian Disney to give $50 million for a concert hall to be built in honor of her late husband, Walt, as an addition to the Music Center. Fleischmann, who had once hailed the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, built for the L.A. Phil in 1964 as an acoustic wonder, eventually pronounced it unworthy. It still is, but that’s another story.

Presumably, Fleischmann assured Lillian Disney that this generous sum would be sufficient for the new hall, knowing full well that much more would be needed (ultimately, more like $274 million). Although Fleischmann and Gehry were close friends, Gehry was viewed as far too radical for the conservative classical music establishment, which feared chain-link fences and whatnot. One Music Center board member proposed that the original blueprints for the Chandler be dug up and that they just build “the same damn thing” across the street.

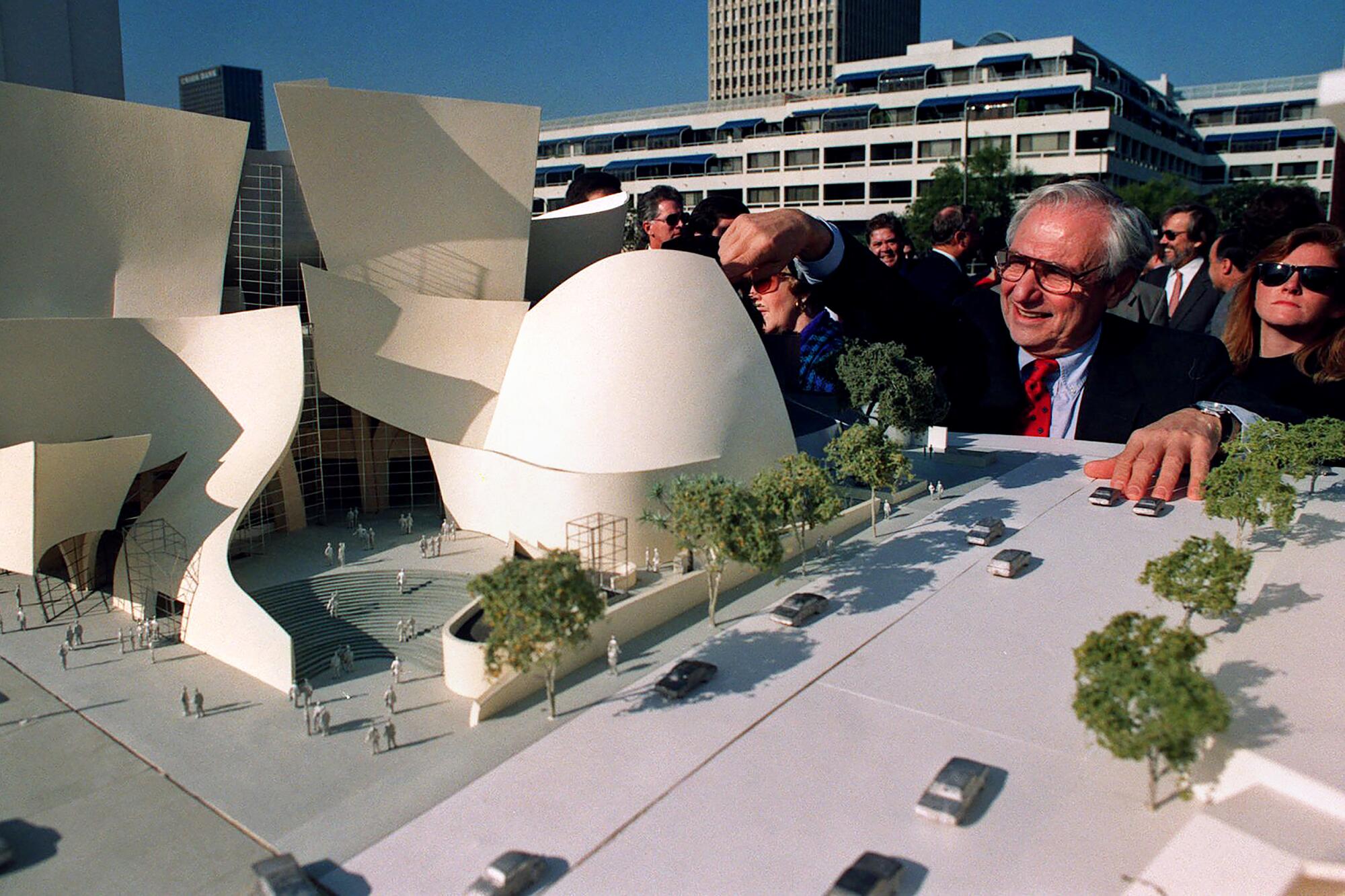

A competition was arranged. Gehry’s model, which was exciting but far more conventional than the masterpiece he ultimately designed, was so superior to the others, especially in its welcoming feeling, that even Gehry’s detractors begrudgingly approved. The four other models, all by distinguished architects, were suspiciously clueless.

I never could get Fleischmann, or anyone else close to the competition, to explain why. Did Fleischmann and others on the jury know all along that Gehry was exactly what the orchestra and the city needed and that the only way to get it was to rig the competition by misleading the other architects? All insisted it was fair. Until evidence proves otherwise, I’m sticking with Fleischmann’s visionary flare eclipsing committee-compromised fair.

It would take 16 years to build Disney. Fundraising stalled repeatedly. Gehry’s detractors (including some leading voices at this newspaper) had a field day. The Music Center did not display much enthusiasm.

In the early 1990s, the L.A. riots, the Northridge earthquake and a recession took further wind out of the new hall’s prospective sails. When I arrived at The Times in spring 1996, everyone told me that the hall was moribund. The county, which owns the Music Center and the land on which Disney sits, had built only the parking lot. The county’s supervisors, with the exception of Zev Yaroslavsky, were ready to pull the plug.

But Fleischmann tenaciously hung on. Much later, Esa-Pekka Salonen, then-music director, confessed to me that he had offered his resignation to Fleischmann, in part over his disappointment of the hall’s seeming failure and figuring that maybe another conductor could do more. There was also considerable disgruntlement among board members and patrons over Salonen’s advocacy of new music, despite the fact that he was attracting a younger audience and was increasingly seen as a vital new voice in classical music.

A fundraising deadline loomed, and Fleischmann persuaded Salonen to stick it out a little longer. Just in time, the tide turned, thanks to three fortuitous events. Gehry’s new museum in Bilbao, Spain, wowed the world. A Stravinsky festival that Salonen and the L.A. Phil put on in Paris wowed not only the French but also L.A. Phil board members, including Disney skeptics. The clincher was a series of individual gifts of $5 million each from the publisher of the L.A. Times, then-Mayor Richard Riordan (using his personal money to make what was at the time an anonymous donation) and philanthropist Eli Broad, who then took over the final fundraising.

Disney opened as an instant icon. It catapulted the L.A. Phil to far greater fame than the orchestra had ever known. It spearheaded the revival of downtown and shaped the identity of DTLA, as it would soon be known.

With Disney, the 21st century orchestra was born. The immediacy of the acoustics, the intimate connection between the musicians and listeners, the warmth and visual allure of the interior — all were thrilling. The new hall invited making and consuming new music seem natural. The interior, shaped a little like a ship, put an audience in the mood for adventure.

For the next two decades, the L.A. Phil went from strength to innovative strength, helped by two progressive music directors, Salonen and, beginning in 2009, Dudamel.

Starting with the “Tristan Project” in 2004, Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde,” conducted by Salonen with video by Bill Viola and staged by Peter Sellars, Disney Hall inspired a full expansion of the notion of what classical music could be. The symphony orchestra, with traditions that go back more than three centuries, now had a venue ripe for experimenting with emerging technologies and for incorporating other musical genres and traditions, even other art forms — be they painting, sculpture, dance, theater, performance art, poetry, cinema, video. The L.A. Phil became a model of how an institution could matter, and its home became a tourist attraction, a site to see and a place to be.

We’ve had a taste of that this season in concerts by Dudamel and Salonen with a range of music, old and memorably new.

At the gala, Dudamel conducted Salonen’s quirky “Fog,” a tribute to Gehry, written five years ago for his 90th birthday. It recalled the first time the composer and conductor heard anything played in the hall while it was under construction.

A few weeks later, Salonen led the premiere of “Tiu,” a big orchestral piece celebrating the hall’s 20th anniversary. Based on the Swedish word for 20, but which also can be Finnish for counting eggs or a musical score, Salonen played with the ordering of 20 chords, turning them into a resplendent phantasmagoric series of dances, fanfares, misty harmonic clouds and melancholic melody.

‘Maestro’ is a compelling movie of Leonard Bernstein’s life off the stage. But it can’t capture what made him a composing and conducting genius.

In what has been an informal festival of Salonen’s scores, the Los Angeles Master Chorale — which has also grown into the big time as the other resident company in Disney — joined the L.A. Phil for Salonen’s wild, dada-inspired “Karawane.”

Dudamel premiered two new works by Mexican composer Gabriela Ortiz, the second of which, “Revolución Diamantina” (Glitter Revolution), a five-act ballet score that revolves around the celebrated 2019 feminist march in Mexico City, is relentless in its sonic invention.

Dudamel’s performance of Stravinsky’s “The Firebird,” Salonen’s of Strauss’ “An Alpine Symphony” and Ravel’s “Daphnis and Chloé,” along with Zubin Mehta’s of Mahler’s First Symphony, sounded unlike they might be played by any other orchestra in any other space — namely site specific, an occasion.

Just this month, British composer and part-time Angeleno Thomas Adès introduced his recent “Five Spells From the Tempest.” When Adès conducted the premiere of his second opera, based on Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” at Royal Opera in 2004, shortly after Disney Hall had opened, the London orchestra sounded lackluster in Covent Garden. The opera seemed a misfire and wasn’t all that more impressive when it went to the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Yet Adès’ 22-minute symphonic condensation of the opera score was a knockout when he conducted at Disney.

So it goes. But Disney has also made us complacent. The sorry fact is that the hall has never been the best it can be, and there seems to be far too little motivation to take the place to its necessary next step, almost as if it were 1996 again.

Downtown has not recovered from the pandemic. The Gehry-designed mixed-use development the Grand opened across the street from Disney in fall 2022 but has yet to come to life, struggling to entice restaurants and retail. It has fixtures in which projectors can be installed to create images on Disney. Gehry originally chose a steel skin suitable for projecting video of whatever concert was occurring at night. That’s never happened. He couldn’t get the Music Center to properly light the building at all.

Gehry also designed an orchestra pit for the hall that was cut because of cost. Earlier this year, he got a chance to try out that notion with a shallow, makeshift pit created for a staging of Wagner’s “Das Rheingold,” for which the architect also designed sets that essentially turned the whole hall into glorious installation art. Installing a real pit, acoustically tuned, should be a no-brainer.

There are the other long-proposed modifications that include turning BP Hall, where pre-concert talks are held, into a full-fledged chamber music hall, revamping the outdoor amphitheater into an enclosed jazz club and replacing the 1st Street steps with a glass enclosed bar that Gehry would name the Ernest, in honor of Fleischmann.

But who is even around to make that happen? Downtown feels grim. County supervisors show little interest in the Music Center. The new Colburn School concert hall on 2nd Street that Gehry designed has just begun construction after bureaucratic delays. The project’s crucial plaza, though, has been indefinitely postponed. An arts corridor on Grand Avenue surely would, as Disney proved, spark a new DTLA resurgence, but City Hall is not acting like it cares.

As for the Music Center: Over the second weekend this month, I attended Pina Bausch’s “The Rite of Spring” in the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and Matthew Bourne’s “Romeo and Juliet” at the Ahmanson Theatre, and I felt like I had wandered back in time.

Bausch’s once supposedly revolutionary Stravinsky ballet, which she choreographed in 1975 when she was just beginning, was included in the first U.S. appearances of her company at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium as part of the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival. Even then, impressive as it was, with magnificently disciplined dancers dashing on a peat-moss floor, it was clear that this was the kind of old-school abstractly modernist ballet that Bausch had outgrown.

Stravinsky’s score to “The Rite” culminated Salonen’s opening night concert for Disney in 2003, and that was all it took to understand what this hall could do. The first recording in Disney was Salonen conducting “The Rite,” and he performed it often enough in the hall, as has Dudamel, that it is a kind of informal Disney theme song.

In the Chandler, Bausch’s company played a recording of “The Rite.” Neither the conductor nor the orchestra of the lumbering performance was credited. The recording quality was coarse, and the score was loudly amplified, a solo bassoon in its mysterious high register sounding like a pigeon being tortured. The “Rite” of Disney was terribly wronged.

At the other end of the recently renovated Music Center plaza, bland and lifeless, Bourne brought the 10th of his choreographic productions to the Ahmanson. This take on Prokofiev’s “Romeo and Juliet,” set in a sanatorium with teenagers climbing the walls, has Bourne’s signature clever movement, which can be delightful, and tons of talent onstage.

But how un-Disney to have those gleaming tile walls for a set. Again; the music was recorded, Prokofiev reduced in length and instrumentation, the score sanatorium-sanitized.

In 2018, L.A. choreographer Benjamin Millepied created a site-specific gender-bending version of Prokofiev’s ballet with his L.A. Dance Project for Dudamel and the L.A. Phil. The dance took over Disney — the stage, the seating areas, backstage, the dressing rooms, the garden — as Millepied followed his dancers around with a video camera. Dudamel conducted a soaring performance, and every inch of the hall came to life. Romeo and Juliet weren’t locked away under key, they were among us, their world ours.

That has been the beauty of Gehry’s creation. He wanted it to be our city’s living room, part of our lives. And he left room for more. But we don’t have a Fleischmann. The L.A. Phil is leaderless without a chief executive and with Dudamel’s tenure ending after two more seasons. Who at the Music Center or City Hall can make anything happen? Time is running out. The 2028 Olympics are practically around the corner. Gehry isn’t getting any younger. And it appears that Los Angeles is not getting any wiser.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.