- Share via

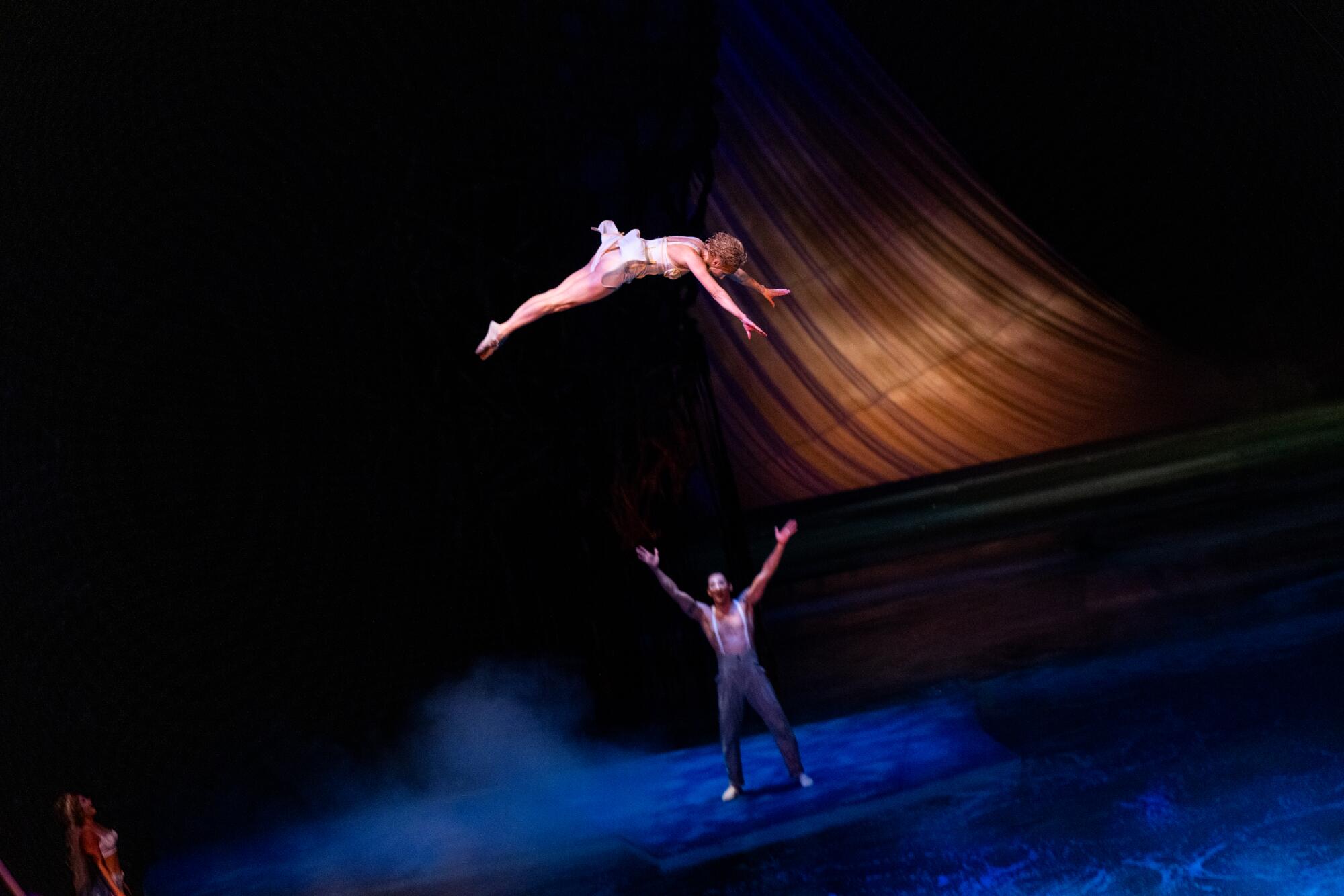

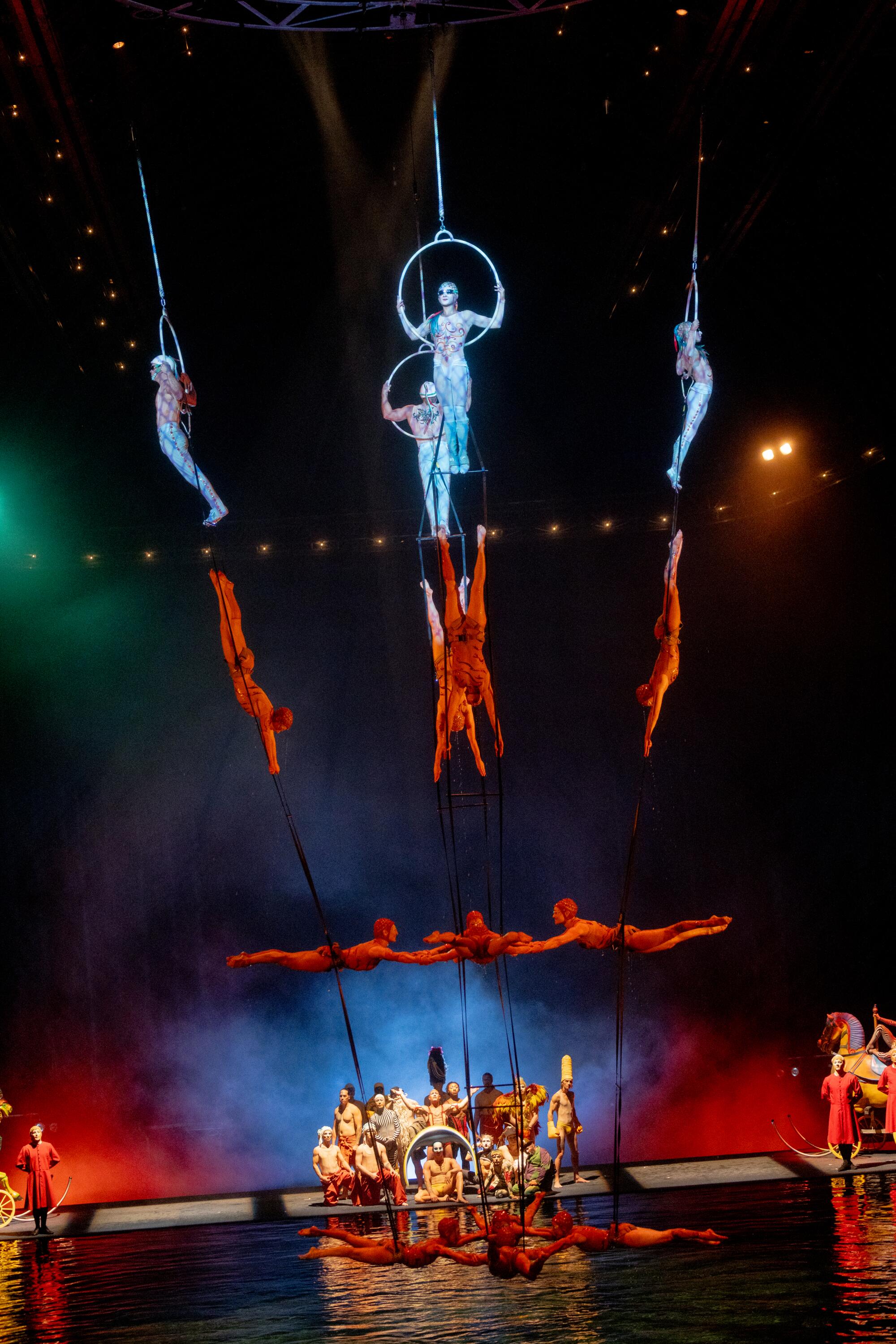

The water is its own world. One and a half million gallons rest behind 11 panes of 4-inch-thick glass in a warren below the stage where Cirque du Soleil’s “O” plays at the Bellagio. This is the lighting tunnel — and when the 25th anniversary show begins in a few hours, spotlights will flood the water through these windows, highlighting the breathtaking acrobatics taking place above and below its surface.

It’s a warm afternoon, but the theater is chilly as Russian swing performer and strongman John Maxson explains the complex mechanics of the pool, which remains a revolutionary build to this day.

Four mainstage hydraulic lifts can move the stage from 17 feet below the surface of the water to 18 inches above it. Instead of regular hydraulic fluid, food-grade vegetable oil fills the hydraulic cylinders powering the “O” lifts — so they don’t contaminate the water in case of a leak. The pool itself is 25 feet deep, but pits for the cylinders extend another 25 feet below that. The pool is drained into the massive lake in front of the Bellagio Hotel and Casino once a year for maintenance, causing the water around the iconic dancing fountains to rise a full inch.

Maxson — his face and bald head elaborately painted, his muscled body sturdy and poised, his posture still impeccable — was among the original 85 performers who opened “O” in 1998.

He said the performers had no idea what they were getting into when they first signed up for the show. They were sent to train at Cirque headquarters in Montreal and lived in apartments together, an arrangement that fostered the kind of intimacy that still defines the human interactions in the show.

“When we first opened, the reception, it was …,” Maxson paused, searching for the right words. “There was a three-month waiting list to get in, which was mind-boggling.”

Vegas has grown exponentially since then; its population has swelled to more than 650,000 from around 400,000. Dirt roads where performers used to park to gaze at the city lights are now fully developed neighborhoods. Casinos have been torn down, built back up, bought and sold. And crucially, what happens in Vegas no longer stays in Vegas. (Woe betide the hapless conventioneer who gets hopelessly drunk at a strip club in the age of TikTok.)

Slogans, technology and trends have changed, but one facet of Sin City has remained the same over the last 30 years: the dominance of Cirque du Soleil.

The French-Canadian company, founded in the 1980s by street performers as a humble yet ambitious circus without animals, opened its first permanent show, “Mystère,” at Treasure Island three decades ago. “I was a little bewildered when Steve [Wynn] told me it was a circus with no animals,” said Bobby Baldwin, the former CEO of Mirage Resorts. Cirque has since grown into a billion-dollar entertainment juggernaut with six shows running twice a night up and down the 4.2-mile Strip, not to mention its worldwide tours.

Cirque in Vegas has performed more than 60,000 shows for 80 million guests. It has 1,790 employees, including 465 artists.

“O” — its most profitable show — has remained practically unchanged across 25 years, 11,000 performances and an audience of 18 million-plus. Its run in a single venue is rivaled only by “The Phantom of the Opera” on Broadway, which recently closed after 35 years and nearly 14,000 shows.

“‘O’ was the most successful stage show in the history of entertainment,” said MGM Resorts International CEO Bill Hornbuckle, who was with Mirage Resorts when it first brought Cirque to Vegas. “It’s gonna gross close to $2.5 billion and it runs 90%-plus occupancy the whole time.”

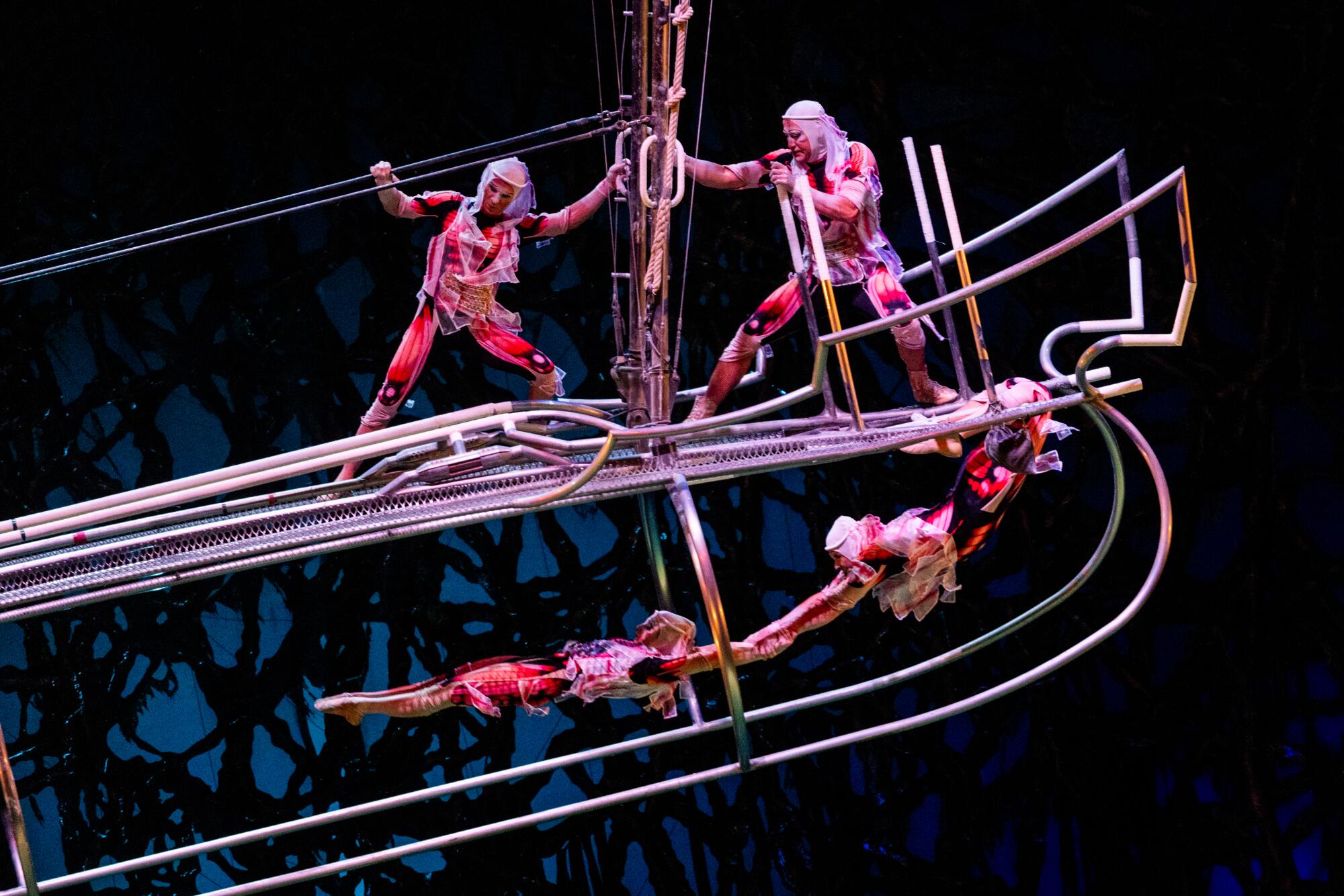

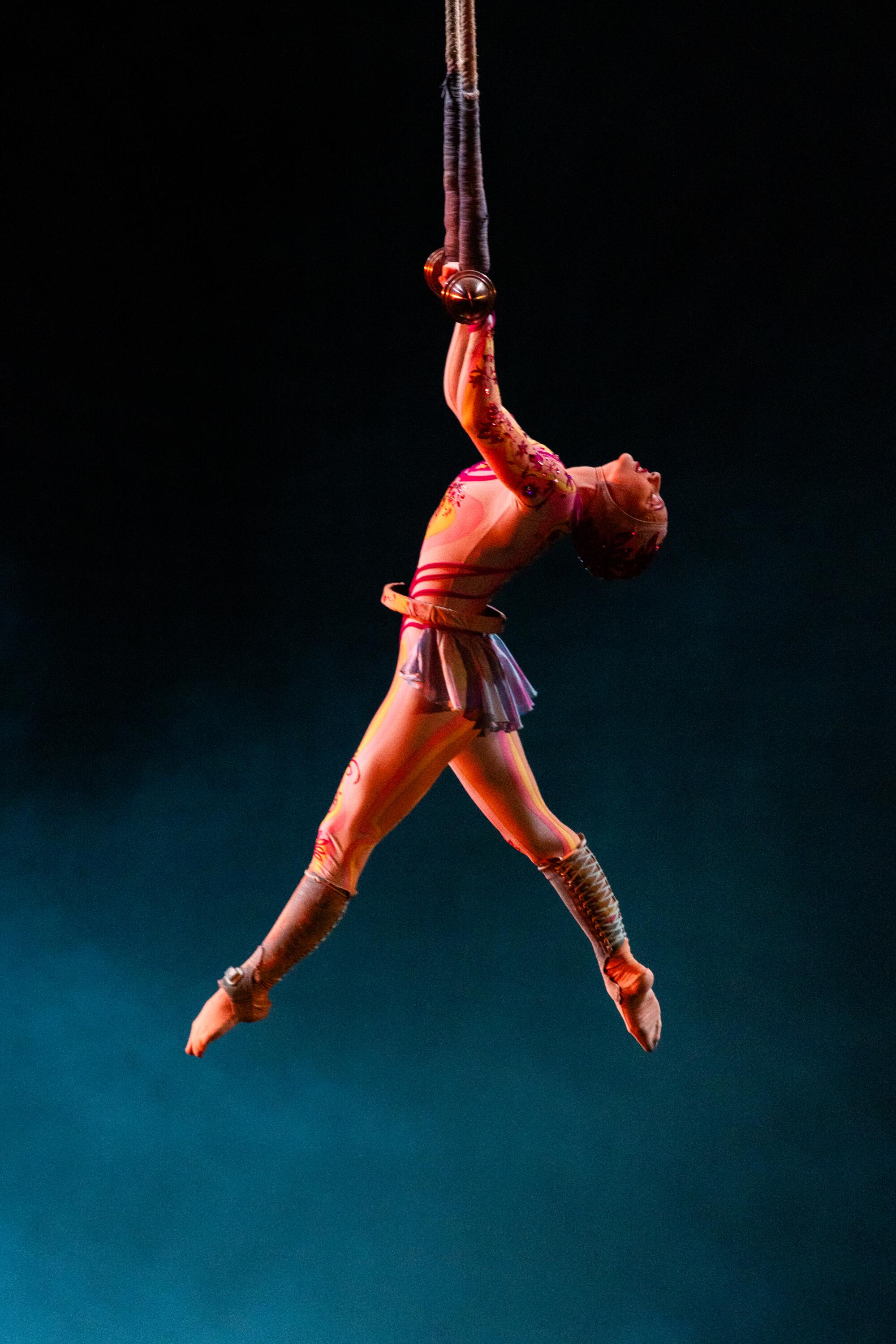

The allure of Cirque shows rests in the unbelievable physical abilities of international performers who are athletes of the highest order — often arriving at Cirque as a second act after competing in the Olympics or playing professional sports. The high-stakes bending, lifting, flying, flipping, rolling, diving, dancing and swimming unravel bit by bit over the course of each show like a surrealist painting come to life.

As in many of its productions, fate has been key to the story of Cirque’s rise. The fledgling company happened to be in the right place at the right time, said Alan Feldman, distinguished fellow in responsible gaming for University of Nevada, Las Vegas’ International Gaming Institute.

When Cirque first hit, Wall Street financing flowed to Vegas along with a growth in tourism and conventions, making the city ripe for a new kind of non-gaming entertainment. In the 30 years since, Cirque paved the path to the city becoming a global destination — as much for its top-notch shows, five-star chefs and tony boutiques as it is for its cards, dice and slots.

Ironically, the tigers of Siegfried & Roy cleared the way for the animal-less circus.

Real estate magnate Steve Wynn made a huge gamble on the future of the recession-battered city in 1989 when he built the Mirage for a then-unimaginable sum of $617 million, making it the world’s most expensive resort. Jay Sarno’s Caesars Palace, which opened in 1966, cost $22 million by comparison.

With the Mirage, Wynn created Vegas’ first fully integrated resort, said Feldman. Under the same sprawling roof, it contained the hallmarks of every modern casino: gaming, dining, meeting and convention spaces, destination entertainment and high-end retail.

The Mirage’s success spurred a building boom that resulted in 11 new mega resorts during the 1990s, including New York-New York, Paris, Bellagio, Luxor, Excalibur, MGM Grand, Stratosphere and Mandalay Bay.

“The capital investment in that 10-year period was like no other destination has ever seen, and maybe ever will see in terms of value of the dollar in that time frame,” Hornbuckle said. “It’s very difficult today to build something at this scale, and make it all pencil out. Back then you could do it.”

Meanwhile, Siegfried & Roy raised the bar for the kind of entertainment expected in Las Vegas. With Wynn’s financial largesse, the German magicians brought in a director and set designer from the Royal Shakespeare Company, and a lighting designer who had won a Tony for her work on Broadway with “Phantom,” said Feldman.

“It was just this incredible deluge of imagery, of symbolism, of art,” said Feldman of Siegfried & Roy’s show, adding that it was the first time anyone had thought to take a Las Vegas show and imbue it with some of the same artistic objectives found in opera, ballet and theater.

It was in this fertile atmosphere — in a tent in a parking lot behind the Mirage — that Cirque du Soleil debuted “Nouvelle Expérience.” The run lasted about a year and a half, and by the end, Wynn had committed to building a theater exclusively for Cirque in his newest casino, Treasure Island. This would become Cirque’s first permanent home.

Baldwin, who crafted all the deals with Cirque beginning with “Mystère,” recalled the initial arrangement.

“I was always of the belief that if we could break even from a business point of view in a tent behind Mirage, going head-to-head with Siegfried & Roy who sold out 1,600 seats a night every night, it would probably do very well in Treasure Island,” Baldwin said. “It not only broke even, it made money back under very difficult circumstances.”

The business plan for the show that would become “Mystère” was fairly simple: Wynn would pay for the 1,700-seat theater, which cost $36 million, and Cirque would cover the show’s costs, which totaled $12 million that first year.

“We’d share the expenses and share in the profits, if there were any — and there were,” said Baldwin. “And we’d also set some money aside to replace the show in seven years because we thought that in Las Vegas people are looking for variety, and not many shows lasted over four or five years. Anyway, we never needed to replace the show.”

Having a permanent theater rather than a roving big top immediately upped Cirque’s game, Baldwin said. Rather than constantly touring, the show lived in a place that was home to 40 million visitors a year — a massive blessing for performers used to life on the road. They could now put down roots and raise families. Days are long for these artists, who often rise at 6 a.m. to get kids off to school before grabbing a nap and heading to the gym for a training session, then working 6 to 11 p.m. on show nights.

“There’s no blanket way that anybody does it,” said Maxson, who met his wife, a wardrobe supervisor, on the set of “O.” “Outside of here, it really is a more normal life.”

Wynn’s bet on Cirque paid off. “Mystère” was a hit, and the other casino owners took notice. They all came to see it, Baldwin said, but they couldn’t duplicate it. Cirque’s contract with Wynn, meanwhile, was exclusive, and soon the collaborators began to embark on what Cirque co-founder Guy Laliberté still refers to as Cirque’s “masterpiece”: the water-fueled phantasmagoria that is “O” at the Lake Como-inspired Bellagio.

The 1,800-seat theater housing “O” — designed to resemble an early Renaissance-era European opera house — cost $168 million to build in the late ‘90s.

“There was a larger market for Cirque in Las Vegas than any of us suspected,” Baldwin said.

Beginning in 1989, gaming revenue in Vegas began to drop in inverse proportion to non-gaming revenue, which included money spent on entertainment, shopping and dining, said UNLV’s Feldman.

When “O” and Bellagio opened in 1998, the two types of revenue had become almost even. By 2018, non-gaming revenue stood at 60%, Feldman said.

The success of Cirque ultimately encouraged new competitors. Big-name acts such as Lady Gaga and Adele are playing sold-out residencies. Celine Dion set a high bar for success; her two residencies at Caesars Palace raked in nearly $700 million cumulatively between 2003 to 2007, and 2011 to 2019. Britney Spears’ residency at Planet Hollywood from 2013 to 2017 netted $138 million and Usher’s 20 shows earned nearly $19 million at Caesars from 2021 to 2022. Vegas is again a hot commodity, with headlining acts growing by more than 200% in the last decade, said Eric Grilly, president of the resident and affiliate shows divisions of Cirque du Soleil, who oversees all shows in Vegas and Orlando, Fla.

Cirque is attempting to change with the times, said Grilly and Hornbuckle, making note of “Mad Apple” at New York-New York, which is a leaner, shorter, more portable show that caters to distractible modern attention spans and turns the showroom into an interactive bar and club.

The short-lived experimental show “R.U.N,” which featured a script by filmmaker Robert Rodriguez alongside rock ’n’ roll-driven motorcycle chases and film stunts, ran only four months before closing in 2020. Still, “it incorporated new technology and storytelling in ways that helped us grow as a company,” Grilly said. “Risk and failure are inherent in the creative process and we embrace both.”

An end of an era came last year when Hard Rock International bought the Mirage for $1.1 billion. That casino houses one of Cirque’s most beloved shows — the Beatles-themed rock extravaganza “Love.” Since Cirque’s contract is still exclusive with MGM Resorts (which acquired Mirage Resorts in 2000), the future of “Love” is up in the air. What Hard Rock will do with the show’s theater is not yet known, nor is it certain that the show will reopen elsewhere. For the time being, it is set to run through 2024.

Grilly rattles off Cirque’s modern competition in a swiftly morphing Vegas: four professional sports teams, with a fifth coming; the $2.3 billion, 18,000-seat Sphere just opened, hosting music acts including U2; the massive 4,300-room hotel-casino Resorts World launched two years ago, alongside a 4,703-seat theater, home to acts like Carrie Underwood and Tiesto; and Miami transplant Fontainebleau debuts in December, featuring the 3,800-capacity, three-level BleauLive Theater, which will welcome rapper Post Malone for a New Year’s Eve extravaganza.

Cirque’s reliance on live audiences made the company particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic and forced it to declare bankruptcy in June 2020. It emerged from bankruptcy in November of that year, at which point its lenders took control of the company, exchanged their debt for equity and infused capital to allow Cirque to rebuild, Grilly said.

“In Las Vegas, after all of our shows were closed for nearly 16 months because of the pandemic, we reopened all of our productions in one six-month span and the audience response has been tremendous ever since,” Grilly said, claiming that Cirque sells more tickets than any other producer in the market. “This has been an unprecedented rebuilding effort that all of us are extremely proud to be a part of.”

Cirque co-founder Gilles Ste-Croix recalled an expression that Wynn was fond of repeating after “Mystère” first opened.

“He said, ‘I really like it when all the other casinos are just sleeping areas for customers because they come to see the show and they stay to gamble in my place,’” Ste-Croix said, laughing.

Hornbuckle said Cirque cracked the code of Las Vegas audiences: “They wanted to be entertained without having to think too much about it. They wanted to be excited, they wanted to be on the edge of their seat, they wanted to see something that they couldn’t see anywhere else.”

For Cirque co-founder Laliberté, the omnipresence of Cirque in Vegas is a far cry from the days when the fire-eating stilt walker performed with Ste-Croix on the streets of Quebec in the early ‘80s.

“At that moment of time there were two capitals of entertainment. One was London and the other one was New York,” Laliberté recalled. “And for me, I clearly saw that potentially Vegas could become another capital of entertainment.”

The scrappy upstart circus had a flair for drama and a deep understanding of the power of human connection. Laliberté discussed the troupe’s 1987 show in Los Angeles in a 1989 story in The Times. Laliberté said the future of the troupe rode on that single show — held in a big top in Little Tokyo for opening night of the Los Angeles Festival.

“If the critics didn’t like us, we wouldn’t have had the money to put gas in the trucks and get home,” Laliberte told The Times. “We were gambling our whole circus on a one-night deal.”

The critics, however, loved it.

“One hesitates to call it ‘poetry,’ but that’s what it is,” wrote then-Times theater critic Dan Sullivan. “Not only do we see the traditional performing skills, executed in a particularly upfront way. … We also see the wonder of possessing such skills. The show has a theatrical frame that’s not just a gimmick.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.