Column: In Malibu, the myth of the open road creates a bloody reality: PCH is a death trap

- Share via

California’s Highway 1 is one of the most famous roads in the country. Stretching from Dana Point to Mendocino County, it offers up the glories of the California coastline: the sandy southern beaches, the breathtaking central cliffs, the Golden Gate Bridge and beyond.

Malibu is, likewise, one of this country’s most famous cities, home to two highly influential, wildly different and deeply Californian cultures: surfers braving the waves and Hollywood A-listers strolling the sand. (Three if you count high-priced celebrity rehab).

But where road and city meet, romance ends — in twisted metal, the wail of emergency vehicles and, far too often, blood and fire and death.

Those seeking the perfect-drive dream of Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu have helped make it a nightmare.

On Oct. 17, Niamh Rolston, Peyton Stewart, Deslyn Williams and Asha Weir became the latest to die on what’s been labeled “Blood Alley,” the 21 miles of PCH that cuts through Malibu.

Fraser Michael Bohm, 22, was arrested at the scene; prosecutors say he was driving 104 miles an hour without a license when he struck a series of parked cars near which the women, all Pepperdine students, were standing. He has since been charged with four counts of malice murder and four counts of gross vehicular manslaughter.

Just days after the crash, Malibu residents packed a City Council meeting to make emotional demands that the city take substantial steps to make its portion of PCH safer.

It’s not the first time these demands have been made. As the body count continues to climb at the intersection of two iconic American treasures, both of which draw countless tourists each year, people have implored the city, the county, the state to do something.

Lower the speed limit, increase Highway Patrol presence and install speed cameras, improve the traffic signals, build sidewalks and/or pedestrian bridges, put up signs reminding drivers that much of Malibu’s PCH is a residential area and that speed kills. Something. Anything.

As producer Michel Shane points out in his new documentary “21 Miles in Malibu,” the thoroughfare has not changed significantly since the 1950s. Shane’s daughter Emily was killed in 2010 at the intersection of PCH and Heathercliff Road, since renamed Emily Shane Way; the driver who killed her was convicted of second-degree murder.

Fraser Michael Bohm, 22, is charged with four counts of murder and four counts of gross vehicular manslaughter.

But Shane says he didn’t make the film out of grief so much as frustration. “This was not about the tragic death of my daughter,” he said. “I started it two years later because in the summer of 2012, it seemed like every other day PCH was closed due to accidents, some of which involved deaths, and I just couldn’t keep quiet.”

Ten years later, “21 Miles in Malibu” is on the festival circuit and Shane finds himself, once again, part of a larger call for change in the aftermath of tragedy.

He says he hopes that the deaths of the four Pepperdine seniors will serve as a tipping point. On Oct. 20, he began circulating a petition demanding, among other things, a reduced speed limit and increased speed enforcement.

“This road was simply not built to handle the amount of traffic it gets,” he said. “And the big problem is that you are limited by the fact that on one side is the ocean and on the other, mountain.”

Anyone who has ever driven PCH through Malibu knows it’s a mess. Along some stretches, homes back up almost right to street, which means residents exit their garages right onto a highway. Strip malls and local businesses, along with the ever-beckoning beaches, have limited parking and no sidewalks, which forces people to walk along the shoulder, often alongside parked cars. The road is narrow, there are constant jaywalkers and too many drivers seem to feel that any stretch that isn’t bumper to bumper offers an open invitation to speed.

Which is, of course, the larger problem. We have been conditioned by film, television and car commercials to believe that any form of open road, particularly one with iconic status, is best experienced in a blur.

Particularly Highway 1, so often touted as the ultimate top-down, music-blaring, troubles-in-the-rearview road trip. Never mind that many of its 656 miles go through cities and towns that, like Malibu, were built up long after the road was laid.

Travel guides love to rhapsodize the vacation possibilities of a trip along the second-longest road in the country, but in many places, including Malibu, the highway functions as a main thoroughfare for residents, commuters and students, some on foot or bicycles.

Unfortunately, when succumbing to the siren call of Highway 1 in general or PCH in particular, too many drivers view the inevitable bottlenecks of cities, towns and campuses as irritations, obstacles to be swerved through, honked at and dispensed with for the “magic” of flying past Leo Carrillo and Point Mugu, Gaviota, Pismo Beach and Morro Bay.

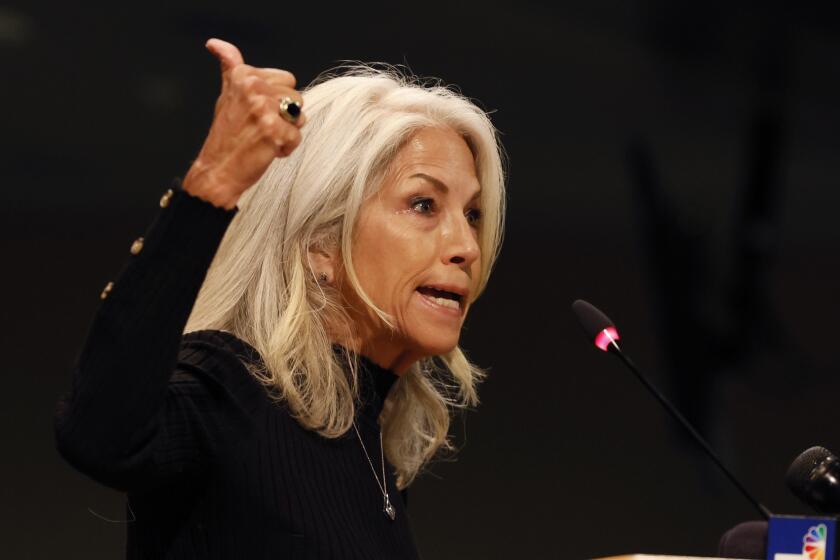

Nearly 30 people spoke at Monday’s emotional Malibu City Council meeting, expressing grief and anger about the deadly danger posed by a stretch of PCH.

Venture farther north and it can get even crazier as self-styled daredevils zip past the zebras grazing in the hills around Hearst Castle to take on the winding roads to and through Big Sur like they’re James Bond or starring in their own personal SUV commercial. (Hint: If your tires are squealing while driving through Big Sur, you are driving too fast.)

Not even the recent road closure at Lucia has eliminated the problem: I recently watched a red convertible come to a squealing, fish-tailing stop at the northern barrier.

In Los Angeles, it isn’t just PCH that’s treated like a cinematic backdrop with often fatal consequences. After being featured in “The Fast and Furious” franchise, streets in Angelino Heights roiled with the type of street racing that has plagued other parts of Los Angeles for years. Angeles Crest Highway remains a draw for reckless driving too; despite increased Highway Patrol presence, there are yearly incidents of motorists taking its curves too fast and driving over steep cliffs.

So yes, Malibu definitely needs speed cameras, sidewalks and more signs reminding motorists that they are entering a residential area. Perhaps, as some including Shane suggest, those 21 miles of PCH that cut through Malibu should be designated as a boulevard rather than a highway, with all the traffic-law changes it would require.

But we all have to adjust our thinking when it comes to every stretch of Highway 1 and the “open road” in general. Speed limits do not exist to thwart you personally from experiencing whatever neurotransmitter rush you might get from driving fast. They exist to ensure you get from Point A to Point B without killing other people and/or yourself.

There is no reason on God’s green Earth for anyone who is not involved in a professional auto race or being chased by actual monsters to drive more than 80 miles an hour, never mind 100. “The Fast and the Furious” is a film franchise; James Bond is a fictional character; and PCH is, in many places, a treacherous road that should be driven with care even if the Beach Boys are playing.

If you need the exhilaration of speed, go on a roller coaster.

Shane says he wants to use “21 Miles in Malibu” to battle the “King of the Road” mythology by creating an educational presentation for high school students. He hopes that a new generation of drivers can be taught the dangers of speed just as previous generations learned the perils of drinking and driving.

In June, Malibu began construction on its new Traffic Signal Synchronization Project, which will allow Caltrans to control and operate the signals for maximum safety as traffic patterns dictate. That’s a start, as are the proposed speed cameras. But until we shake the whole “need for speed” mentality, PCH will become better known for smashed cars and shattered lives than palm trees and the glittering Pacific.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.