Screenwriter Eric Roth on ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ and a life of big scripts

- Share via

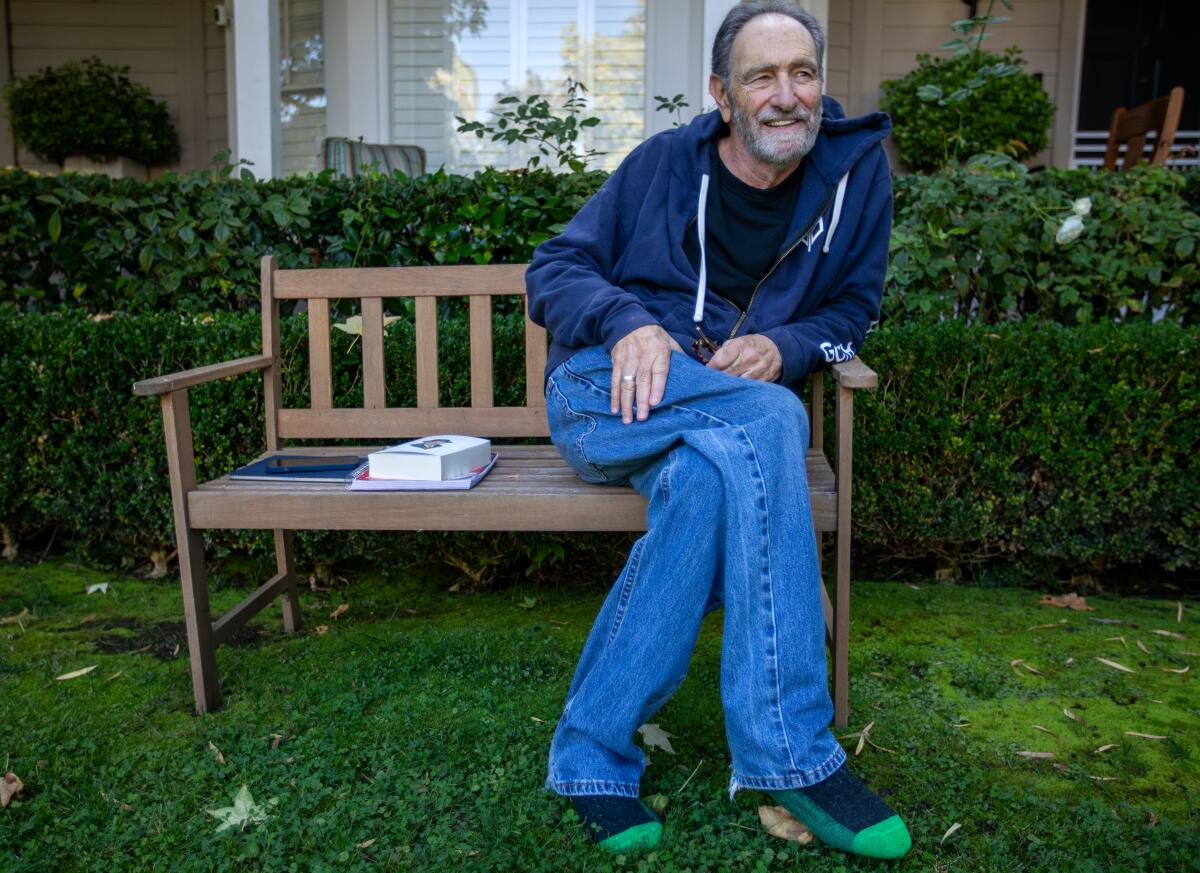

The man on the porch wonders about what will endure, the stories, voices and years, the way they gathered and played out, making him a recurring whisper in the lives of others. If he were writing a movie—and he has written many— he might pencil in for the camera to linger on the gray beard, wrinkled eyes and the way the face, shadowed by a ball cap, looks to the house across the street.

What will happen to the ones who live there? How will it all turn out when he is gone?

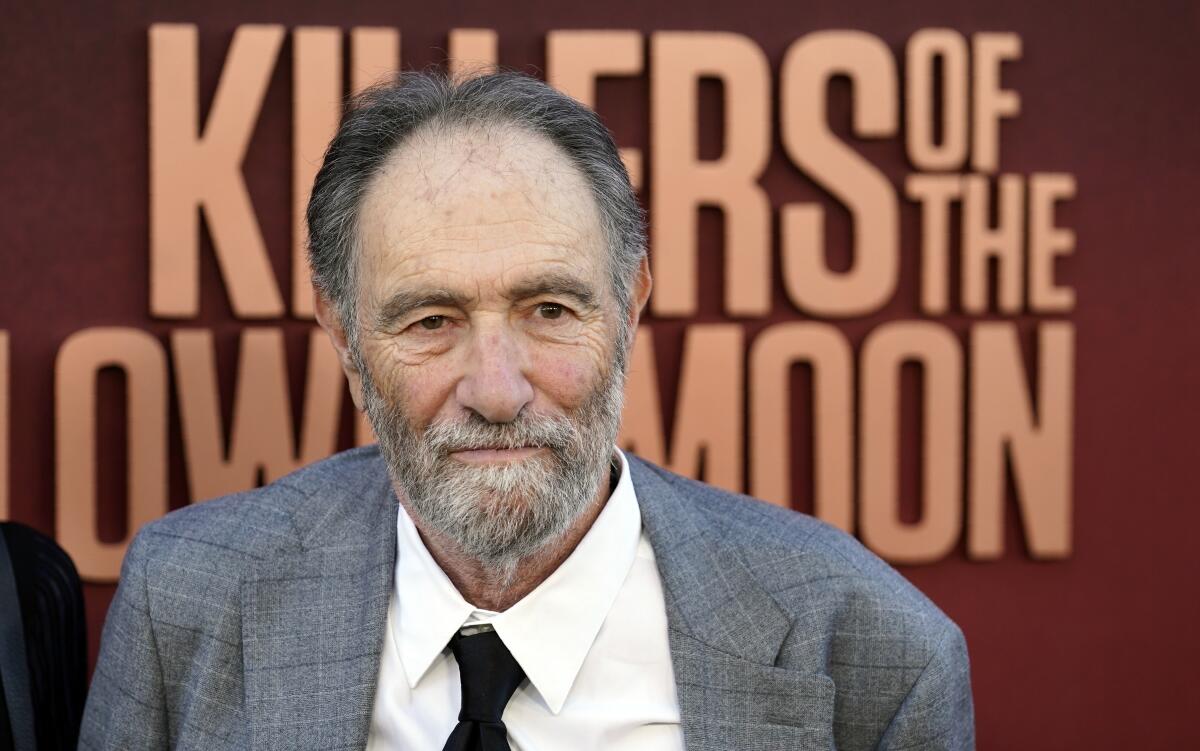

Many words stretch ahead before then, and Eric Roth, who bets on horses and is nearing 80, is busy on scripts for two love stories, a science fiction fantasy, a pilot for a possible Netflix series about the Kennedys, an ecological tale, a stage adaptation of “High Noon” and preparing for Friday’s opening of “Killers of the Flower Moon,” a 1920s crime saga he wrote with Martin Scorsese about greed and murder against Osage people in Oklahoma.

Roth is one of the most successful and admired screenwriters in Hollywood. He’s been nominated six times for an Academy Award for adapted screenplay, winning with the whimsical and much-loved “Forrest Gump.” He’s worked with Steven Spielberg, Michael Mann, David Fincher, Akira Kurosawa and other important directors. He’s a master at narrative and knows the intersection of artistic integrity and commercial appeal. But like a boy showing his mother a good report card, he, even after all the citations, seeks validation, an inclination shared by many in this town but seldom expressed.

“Maybe something you can say [about me] is that you probably don’t know this person but he’s been part of your life with all these movies,” said Roth. “I was always a good writer and I got things made, but nothing probably that very good until ‘Forrest Gump’. That opened up a whole world.” He added: “I wouldn’t mind if I could go back to being 50 and know what I know now. I want to enhance whatever I’ve done.”

That is Roth, looking back, peering ahead. What is the essence? The legacy? He is at once confident — he might be thinking as he reads this, ‘Hey, let’s limit the exposition and stick to subtext’ — and a fierce and honest critic of his work and that of others. When speaking of the praise that has come his way, he pauses and smiles — he has the mischievous eyes of a bookie — and says, “I would trade all my movies for ‘Sunset Boulevard’ or ‘The Treasure of the Sierra Madre’. Wouldn’t you?”

The breadth of his films over six decades is an exploration not only of cinema but also of the fascinations and torments of mainstream America, from the propulsive intelligence of “The Insider,” the story of a tobacco company whistle-blower; to the remake of “A Star Is Born”, starring Bradley Cooper and the comet of fame that is Lady Gaga; to the short film “Ellis,” where Robert De Niro wanders through an Ellis Island snowfall as an unrequited ghost. Roth’s instincts and empathy for his characters — a number dwell at the crossroads of isolation and redemption — are grounded in a humanity that can be fanciful, searingly real and, as critics have noted, occasionally sentimental. Like life.

“Eric is Forrest Gump personified, with the feather floating down and all that crap. He’s a romantic,” said Jeffrey Woody Copland, who met Roth nearly half a century ago at the Del Mar racetrack in a shared passion for betting on horses, which later led to Roth’s work on the HBO series “Luck.” “But then you’re with him at the track and he’s trying to solve an equine puzzle. He’s competitive as hell. If he could handicap horses the way he can movies, well, he’d be onto something.”

A writer’s ego is often as thin as a moth’s wing, especially in the collaborative world of filmmaking, where, unlike the novelist, the singular vision belongs to the director, not the scribe. Roth has felt the sting of the subservient. Robert Redford replaced him with another writer on “The Horse Whisperer,” and Spielberg brought in playwright Tony Kushner to work on Roth’s script for “Munich,” a morality play about Israeli assassins targeting Palestinian militants. Such are the nicks and acceptances of the trade. In the best cases, Roth said, a “third rail” version rises between writer and director.

“I fight with everybody. You just don’t get why they don’t get something,” he said. He was hurt by Kushner’s hiring, but Roth, who shared a screenwriting credit, called “Munich” a wonderful film and has noted that he would never write anything as inspired as Kushner’s Tony award winning “Angels in America.” Often in conversations with Roth, one hears how the battler — he boxed as a youth in Brooklyn — holds his ground until that moment not of surrender but of equanimity.

“I think everybody [directors] have done pretty great by my words,” he said. “In most cases, they’ve probably improved everything to some extent.” A few beats later, he takes himself to task: “I think I screwed up the movie ‘Suspect’ which Cher was in. I should have had the Liam Neeson character be guilty and not all the melodrama I put at the end.”

He has had a few notable disappointments, including “Lucky You” (2007), a screenplay he wrote with Curtis Hanson about a Las Vegas poker player, and the overwrought post-apocalyptic “The Postman” (1997), which was co-written with Brian Helgeland and starred Kevin Costner. The TCM biography page for Roth notes that the film “proved to be almost ruinous for all involved, especially Roth, who had, up to that point,” a number of misfires and only one big success. But after that, wrote TCM, Roth’s career “began an upward trajectory that rarely wavered off course.”

“Eric is on fire right now creatively,” said director, writer and producer Judd Apatow. “He’s funny and wise. It’s almost comedic how strong his work is. When you’re young, you have this madness of wanting to establish yourself and make your name. Eric never lost that. He’s always in the same emotional space about it. He’s hungry like he just broke through, even though he did many decades ago.”

He added: “All writers are tortured, but of all the writers I know, Eric seems to be in the least amount of pain.”

On recent afternoons, wearing jeans, slippers and a loose shirt, Roth came down from his writing desk and sat on the porch. The quiet was at times broken by a workman’s hammer, a carpenter’s saw and Ernie, the mailman, who waved and retreated with his bundle into the shade. Roth crossed his legs and settled in, ruminative and open to possibility, as if a nephew or cousin had dropped by to catch a bit of news.

“How do you want to do this?” he asked an interviewer.

“Let’s just talk.”

“Yea, I love that.”

The air was cool and Roth, 78, who is as sly as he is reflective, mentioned the meticulousness of Fincher, with whom he worked on “Mank,” and the generosity of Scorsese. He noted that the novel “Moby-Dick” was about the burdens and complexities of man. He wondered who Shakespeare looked to for inspiration and remembered that day in the late 1960s when he and his first wife were “very loaded on acid” when they sat through “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Three times.

Much has changed since then. Streaming, superheroes and corporate takeovers have reshaped the film industry, and the 40-foot screen has shrunk, for many, to a glimmer in the hand. The kinds of movies Roth makes are becoming rarer. He understands. You can’t build shrines; you have to adapt to new forces, which he discovered when he did not anticipate the phenomenon of binge TV while an executive producer on Netflix’s “House of Cards.” But still, he said, “What was Fellini about? Kurosawa? How about Kubrick in ‘2001’? Those kinds of movies will continue. People will pop up with something extraordinary. But they’ll be fewer and far between because they’re harder to get done.”

That seemed the fate of “Here,” which he and Robert Zemeckis, who directed “Forrest Gump,” adapted from a graphic novel about events that unfold — from dinosaurs to families — on a piece of property over millenniums. It stars Tom Hanks and Robin Wright. “The Gump team was back together,” said Roth, “and we thought, ‘Oh, my God. We’re going to have a wild success.’ We sent it out for auction. Crickets.” The film was eventually backed by Miramax and will be released next year by Sony Pictures.

“Eric has left a deep imprint on American cinema,” said Scorsese, who worked closely with Roth on detailing Osage traditions and customs in adapting David Grann’s bestseller, “Killers of the Flower Moon.” “His sheer breadth of his interests and his knowledge. His remarkable sense of structure. His collaborative nature. His feeling for moviemaking and how it works . . . of how what’s on the page has to translate to what happens up there on the screen.”

Starring Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio, “Killers of the Flower Moon” is a dismaying portrait of American racism as white opportunists seek to fleece the oil wealth of the Osage. The screenplay winds through backroom plots, burial ceremonies, mysticism and the intimacies of a husband and wife caught in a deadly crucible. Roth’s characters are both evil and righteous, cast against a nation’s troubling history.

Roth was a “red diaper baby,” the Jewish son of communists; his father was newspaperman and university teacher and his mother was an executive at United Artists. He grew up in a house of literature and made his way as a boy to the Paramount Theater in Brooklyn, where he watched “Invaders From Mars” from the balcony. Then came “Giant” and “Lawrence of Arabia” and the big studio films that would collide with new realist auteurs who would bring “Easy Rider” and “Bonnie and Clyde.” Roth worked with underground filmmakers and attended UCLA film school, where he won the Samuel Goldwyn Writing Award.

“I found this medium that could capture it all and give you an emotion and leave you with an image in your head,” said Roth, whose family moved to Los Angeles when he was in high school. “I think Francis Ford Coppola said that the great movies exist on some other side of the moon where Don Corleone is still alive. They just continue to go on and you know [inside] what those moments are. I have tried to do that. I think I’ve succeeded.”

How words move, their shades and colors, the way they rise and spin, hit bone or soar toward the cosmos, fill Roth’s mornings in an office where he writes next to his Oscar and a framed photo of a marquee advertising his early film “The Nickel Ride.” He was known for years for long scripts laced with prose. When he was working on “The Insider,” he wrote a scene with more than a page of monologue for Al Pacino, who played Lowell Bergman, a “60 Minutes” producer. Pacino looked at the passage and said, “I can do that with a look.”

“What you leave out is more important than what you leave in,” said Roth. “The silence is telling. I’m not as good at that. I want to say things. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve tried to say less. Less is more. I’ve always believed in that but sometimes I run on. You have to keep people on the journey. It’s so hard to do well.”

“Subtext is the key,” he added. “That’s the best writing. I’m getting there still. The great novelists, painters and filmmakers can do it.” He talked more about writing as if the porch, where a cane waited by the door, were a confessional of sorts, where words were parsed and measured into a disarming self-awareness. “I’m a frustrated novelist. I wish I had written a book. I feel like I’m not a complete writer. That’s real writing to me. Screenwriting’s a great craft. I think you can be artful at it. I’m not sure it’s a great art form, though.”

The best of Roth’s scripts have the expanse and idiosyncrasy of a novel and inspire indelible moments. Forrest Gump (Tom Hanks) sitting with a box of chocolates recounting his life story — a Zelig in history — on a bus bench in Savannah, Ga.; Lowell Bergman (Pacino) standing in the waves of an approaching storm, desperate to keep a phone signal as he calms an anxious and nervous source; Benjamin Button (Brad Pitt) aging backward, rewinding from old man to infant in a tale about the mysteries and heartbreak of time and mortality. Part of the sentiment in “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” comes from Roth asking his mother on her deathbed if she was afraid.

“She said, ‘No. I’m curious.’”

Roth has had three wives, including current spouse, Dr. Anne Peters, an endocrinologist who specializes in diabetes and is a professor at the Keck School of Medicine at USC. Among Roth’s children are Alec, a director; Geoffrey, a screenwriter; and Academy Award winning documentary filmmaker Vanessa. He loved writing amid the chaos and voices of family, but wondered, as one of his characters might do, whether he was a good husband. Something was broken and selfish with him, he said, not his wives. He wasn’t specific but he gave an anecdote, perhaps a metaphor, of being younger and more wild and going to Tower Records at 2 a.m. and then to a diner at 4 a.m.

“That wasn’t necessarily fair to my wife,” said Roth, who also has six grandchildren. “I never wanted to feel I was trapped in the quiet lives of desperation. I’ve grown up. I don’t feel the same desperation.” He added: “I always loved a house full of children. When they grew and left and I couldn’t hear their footsteps anymore, it broke my heart.”

A moment of beauty in one breath; in another, a flaw in the fabric, like that day in 2008 when he learned within hours that he had been nominated for a Golden Globe and that he had lost his retirement money in Bernie Madoff’s multibillion-dollar Ponzi scheme. “I’m the biggest sucker who ever walked the face of the Earth,” Roth said at the time. He later recouped a fraction of his savings.

“Eric is very comfortable criticizing himself and even more comfortable criticizing you,” said Apatow, who often stops by Roth’s porch and gives him scripts to read. “He will not hold back. He will tell you the truth every single time. You almost have to mentally prepare yourself to sit down with Eric. It doesn’t mean he’s right. But Eric is totally comfortable offending you, very constructively, very thoughtfully.”

It is the restlessness in him, as if a man content but unfinished, a writer in need of a perfect sentence, a clever twist of dialogue. So much is in the details; the ones seen and unseen that draw a character in full. When Roth was working on “Year of the Dragon” (1985), starring Mickey Rourke, who played a cop, the actor was given a wallet with a draft card, a license, pictures and a fortune cookie message.

“I’m not sure Mickey ever looked at it,” Roth said, “but it was to me an embodiment of what you need to prove a character, so you know all his psychological manifestations, what his childhood was like. What’s his voice? Voices have to be different and individual like we all are.”

He’s found voices in many places, conversations overheard, memories recalled, a song on the radio. At times, psilocybin — he did a lot of hallucinogenics in the 1960s — helps his creativity. “I do more than microdose,” he said with a reminiscing smile. “If the floor isn’t opening up beneath me, then it’s no good. That’s what scares people. It can be dangerous if not done correctly. But it takes away some of the things that have stopped you from discovering yourself. You can be more available.”

He is reminded these days of human frailty. Screenwriter Bo Goldman, whom Roth revered, died at age 90 in July. He visits TV writer and producer David Milch, who is the same age as Roth and has Alzheimer’s. Roth turns out screenplays quicker than he used to and tends to the “wide universe of people I adore.” Not long ago, he attended De Niro’s 80th birthday party in New York. Scorsese was there along with other older actors and filmmakers whose work may long play on the other side of Coppola’s moon.

So much comes back to the porch. The afternoon light and cool threads of ocean air. The slipping away of time, a phrase, a gesture, the way a child glides across a lawn or a man with fewer years ahead than behind finds recompense. He spoke of exploring “some definition about God, and maybe he doesn’t exist. But this whole idea of what comes next is important. Even if it’s oblivion. I’m still trying to figure out what’s next. Maybe I’ve got two, maybe 10 years left. Put the morphine in me. What am I thinking about? Is it like my mother, ‘I’m curious.’ Is it fear? I don’t know.”

He let the question linger. He doesn’t mind silences. There are stories beyond words.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.