Leading theater while Black: Sheldon Epps on fighting the medium’s long-standing whiteness

- Share via

Sheldon Epps became the first Black person to lead a major theater in Southern California when the Pasadena Playhouse appointed him artistic director in 1997. At the time, he was one of a handful of Black artists in the country to hold such a position. The distinction, says Epps, was an honor imbued with great difficulty.

“I felt bound and required to be successful. Not just for myself. I had to deliver in every possible way in order to prove that it was possible for a person of color to run such an institution successfully,” Epps writes in his recently published memoir, “My Own Directions: A Black Man’s Journey in the American Theatre.” “This was a tremendous extra burden to bear in a position that was already full of its own challenges and obstacles.”

More than 25 years later, Epps’ feelings mirror the fraught conversations the theater world is currently embroiled in. After the murder of George Floyd, the resulting waves of mass protest swept into the arts world in 2020, and theater makers began speaking loudly about a lack of diversity and racial parity on and off stage as well as in leadership ranks.

In June 2020, a collective of BIPOC theater practitioners demanding accountability and change in the art form released a call to action, “We See You White American Theatre.” The initiative had over 300 signatories including marquee names like Lin-Manuel Miranda, Cynthia Erivo and Billy Porter. That number has since ballooned to more than 100,000 signers, and the work of cultivating anti-racist theater systems has been ongoing.

Radha Blank’s ‘Forty-Year-Old Version’ on Netflix highlights racism in the theater industry. We asked 40 Black theatermakers for their stories.

Epps is heartened to see this activism — in fact, the modern movement is part of what inspired him to write his memoir in the first place. With it, he wanted to let young Black artists know that they are not alone and that they can succeed. Still, he says it’s frustrating to recognize his struggle reflected in so many people’s experiences more than a quarter of a century later.

Why has lasting, systemic change proved so elusive in theater — a realm that touts its enlightened liberal credentials but time and again fails to achieve the values it purports to support?

Epps attempted to parse that question in an interview on the sun-dappled patio of the Pasadena Playhouse, near a bench where he sat many years ago watching patrons enter the theater and wondering why he was the only Black face among them — and how he could change that dynamic.

“Let’s not kid ourselves that these conversations started in 2020, they did not,” Epps says, his voice precise and commanding — the voice of an actor, with the poise and posture to match. “Actively, loudly or covertly, I’ve been talking about this for decades.”

Tremendous strides have been made, he says, but the art form is still “fighting a long tradition of the American theater as a white institution, and the power in the American theater, both commercially and in the not-for-profit world, being in the hands of the white establishment.”

Epps says he feels a bit nervous about the way the situation has played out since 2020. He’s heartened to see an increase in the number of leaders of color as artistic directors and executive directors, but he fears that “it’s a moment and not a movement.”

Epps has been privy to far too many of those moments. And now, when theater is faced with one of its biggest challenges ever — regaining financial footing and attracting new audiences in the wake of the devastating COVID closures — he’s afraid many houses will cut staff or close entirely. If that happens, he says he’s anxious that some BIPOC leaders will pay the price.

Sikivu Hutchinson produced her play ‘White Nights, Black Paradise’ with success despite rejection and a poor review from the ‘white theatre regime.’

People will say, “Well, you see, they can’t do the job. You know, we tried, but they’re really not up to it,” Epps says. “And they’ll forget about COVID. They’ll forget about lumber costing more, and union costs, and all of that, and just point the finger, and use that as an excuse to reverse some of the progress that has been made. I pray that that’s not going to be true. But I do have some real trepidation about that.”

Epps speaks from experience. When he first arrived at Pasadena Playhouse, an alt-weekly called City Paper published an inflammatory piece of commentary titled “Theatre of the Absurd,” which began with the line, “Sheldon Epps may be just the man to bring new flavors to Pasadena, a town known mostly for its vanilla.”

The story, which lauded the decision to hire Epps but questioned his chances of success within such a white institution, went on to ask: “Is Epps the man to satisfy the geezers, galvanize the hipsters, placate the board of directors and keep the closet racists at bay? If so, this Black artist leader in a racially complicated community has his work cut out for him.” In his memoir, Epps recounts how his mother “bowed her head and softly cried” when she read the article, which was accompanied by a cartoon of Epps submerged in a boiling cauldron of oil flanked by WASPy white folk.

Born in Compton Hospital in 1952 and raised in the neighborhood until middle school, Epps recalls being part of a generation of young Black people who were told they could be absolutely anything they set their minds to. His father was a minister for the Presbyterian Church and in the 1940s had started the first Black congregation of that denomination in the West.

The church engaged the community artistically as well as spiritually, and Epps recalls a pivotal afternoon when he was around 10 years old and took a bus on a church-organized trip to see a matinee of Carson McCullers’ “The Member of the Wedding,” starring Ethel Waters. The experience caused Epps to fall in love with theater. In a twist of fate, that show happened to be at the Pasadena Playhouse.

Epps’ father was later asked to join the church’s administration, which was housed in New York City, and when Epps was in middle school the family moved to Teaneck, N.J. Uprooted from the community of Compton, Epps soon learned how it felt to be one of the only Black faces in school — a feeling that would last as he moved into the realm of theater for his career.

The choice to devote himself to the art form came as he submerged himself in the magic of Broadway during high school — when he wasn’t busy acting in school plays, he regularly took the bus to Manhattan to see as many shows as he could. He was later accepted into the elite theater program at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

From there he became a freelance director, eventually landing at San Diego’s Old Globe theater as associate artistic director before making the leap to leading Pasadena Playhouse, where he would remain for the next 20 years, programming an eclectic range of shows that drew crowds from all over the city and the region.

Epps writes passionately about his artistic journey in his memoir, noting that it was important to him to not be thought of as a “Black director.”

“In the way that term is used and interpreted in our field it is, by intention or not, demeaning and intended to be diminishing of one’s abilities,” Epps writes. “The fact is that I have never heard my colleagues of the lighter hue described as White directors.”

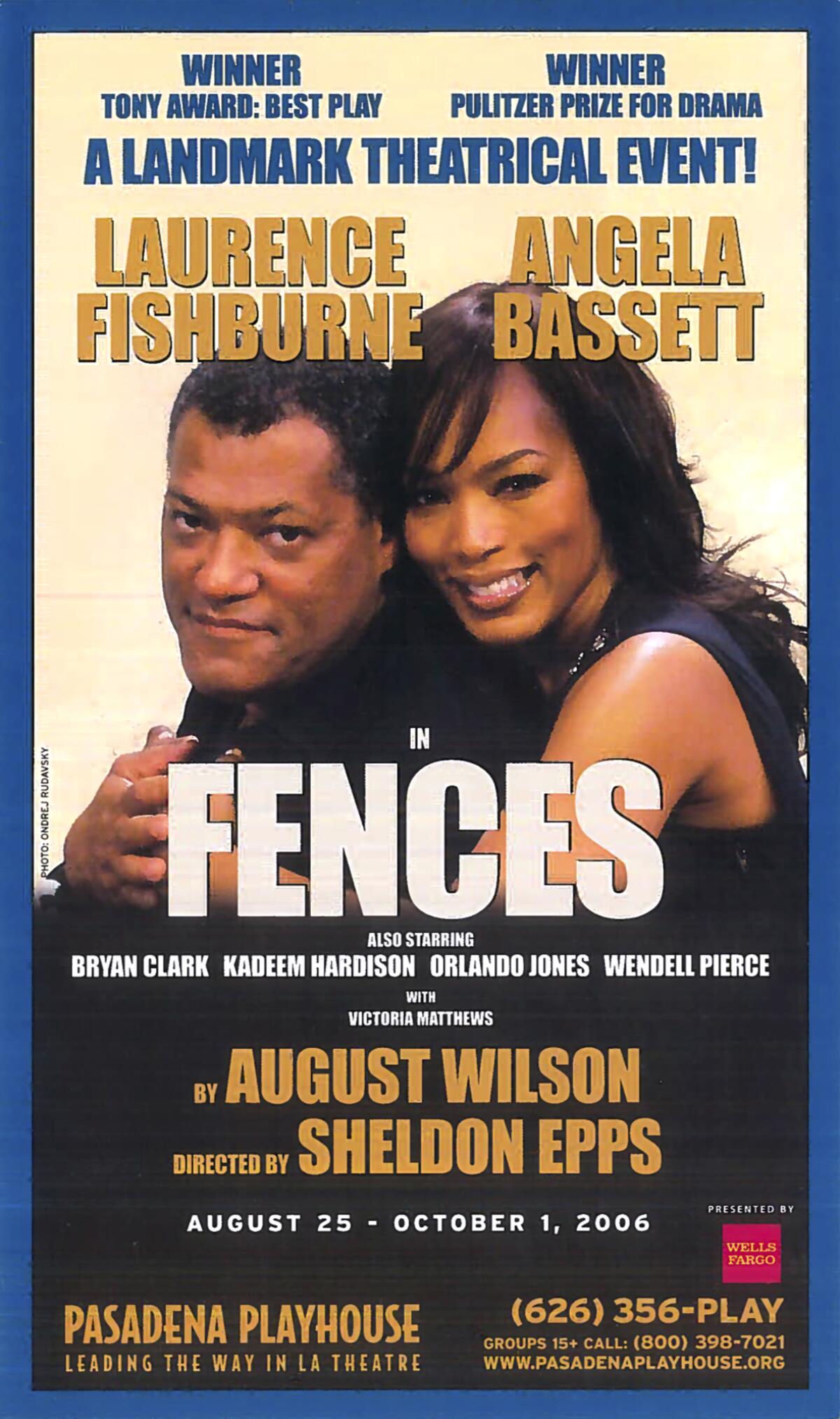

Among the proudest accomplishments of his tenure at Pasadena Playhouse: A 2006 production of August Wilson’s “Fences,” which Epps directed, starring Laurence Fishburne and Angela Bassett; the premiere of “Sister Act: The Musical” that same year; a 2011 production of “Blues for an Alabama Sky,” starring Robin Givens; 2012’s staging of “Intimate Apparel” by Lynn Nottage; and a production of “Twelve Angry Men” tweaked to feature six Black characters and six white characters, and produced shortly after George Zimmerman was found not guilty in the killing of Trayvon Martin.

Epps succeeded in bringing diversity to the stage and audience at the Pasadena Playhouse despite tremendous odds. His accomplishment is a source of pride but came at a great personal and emotional cost. He writes about not being invited to dinners and holiday parties of board members and major donors, and about patrons canceling subscriptions because he was programming too many Black plays.

By the time Epps stepped down from his role in 2017, the Pasadena Playhouse had been transformed. But that work in theater is ongoing, says Epps, and is as necessary now as it has ever been.

“There were years when it was me shouting into the wind and nobody was really listening,” he says, adding that despite many setbacks, real progress has been made. “There are more voices now. They’ve been louder voices. They’ve been voices of great renown, and they’ve definitely been more honest.”

In his memoir, Epps writes about “the dark secret of American theater,” describing the “ghettoizing of artists of color in our supposedly highly evolved, liberal and openminded field.”

That secret, he says, is no longer, “a hidden secret — we haven’t solved the problem — but at least it’s not a secret anymore.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.