Review: The play ‘Home Front’ confronts the bitter realities of post-WWII racism, homophobia

- Share via

There’s a thin line between comedy and tragedy, as Othello and Romeo and Juliet could attest (had they survived their plots). If only this had happened instead of that. If only the timing had been different or a certain heedless action avoided, the longed-for happy ending might not have been preempted by calamity.

In “Home Front,” playwright Warren Leight imagines the lives of an interracial couple whose hopes for the future at the end of World War II are systematically dashed by the slow pace of societal change. The issue here isn’t fate or character shortcomings but a flaw in society itself.

Full of optimism when they meet during V-J Day festivities in New York, Lt. James Aurelius Walker (C.J. Lindsey), one of the few Black naval officers during WWII, and Annie Overton (Austin Highsmith Garces), a widow eagerly looking for a new start for herself and her country, fall in love not just with each other but also with the prospect of a more evolved America.

The play, which is having its West Coast premiere at the Victory Theatre Center in Burbank, was apparently inspired by “V-J Day in Times Square,” the famous photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt of a returning serviceman sweeping a total stranger off her feet and planting a kiss on her lips. Leight wondered what it would have been like had a Black man and white woman been similarly swept up in the jubilation of the moment, though in this scenario what transpires is more complicated than a fleeting romantic impulse.

After running off together on a whim, Annie and James decide to spend their lives together. She finds an apartment on the Lower East Side, a dismal basement bunker that is one of the few options available to a white woman looking to rent a home for herself and her Black husband. (The marriage certificate will have to wait until James is officially discharged from the military.)

There are three characters in “Home Front,” and Edward Glimmer (Jonathan Slavin), a gay window dresser who is similarly navigating a tricky path between freedom and intolerance, plays a crucial role. Fast friends with Annie, he tries to ease the roadblocks he understands only too well from his experiences as a gay veteran. Seriously injured in battle, he collects disability for his war wounds and tries not to dwell on the psychological scars of having been demeaned and ostracized by his fellow soldiers.

Understandably proud of his service with the Golden Thirteen, a small group of Black enlisted men who were made officers after excelling in the officer training program that had been opened up to them at the urging of Eleanor Roosevelt, James is not prepared to swallow his dignity to placate white bigots in or out of the military.

Love doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It needs communal soil to flourish. And James and Annie are on hostile ground in peacetime America, which denies them decent housing, employment and, most bitterly of all, respect. (Set designer Evan Bartoletti grimly sketches the tenement bleakness.)

Edward’s interventions on behalf of Annie to help James after he’s placed in military prison on clearly racist charges only leave him feeling less of a man. In one of the most powerful scenes of the play, James unleashes his fury at Edward, his anger detonating in homophobic slurs that are an indication of how racial injustice has broken his noble, disciplined spirit.

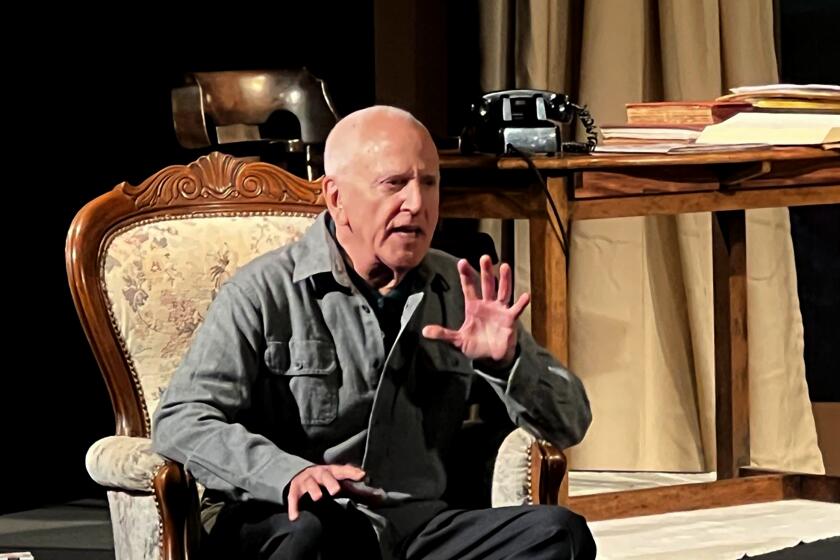

Tony winner John Rubinstein stars in Richard Hellesen’s biographical drama “Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground,” a Theatre West and New L.A. Repertory presentation at the Hudson MainStage Theatre.

Author of the Tony-winning drama “Side Man,” Leight has had tremendous success in television as a writer-producer on the “Law & Order” franchise, HBO Max’s “In Treatment” and FX’s “Lights Out.” His professional polish is on display in “Home Front,” which carefully arranges the storytelling so that nothing is left to chance.

If anything, the succession of scenes might be a touch too orderly. The drama sometimes has the feeling of a treatment — the blueprint for a work that has yet to discover its organic detail.

This is not to slight the production, muscularly directed by Maria Gobetti, co-artistic director of the Victory Theatre Center. Her actors understand their roles perfectly. Garces provides a touch of flightiness and gobs of tender poignancy as Annie; Slavin supplies sparkling wit and a shadow of loneliness as Edward; and Lindsey conveys stoic strength that turns by degrees to rage and regret as James.

Slavin has the audience eating out of the palm of his hand in a role that toys with stereotype but achieves surprising depth, despite the one or two moments when Edward uses language more befitting of a 21st century dean of diversity. Garces occasionally calls attention to the melodramatic flourishes of the writing, but she is most natural in her character’s romantic devotion to James and in her easy banter with Edward.

But it’s Lindsey’s James who startles the play out its predictable maneuvers. His performance exudes the courage of an actor who cares more about his character than audience approval. That he wins it anyway is a credit to his truthfulness as a performer.

Leight doesn’t prettify the ugly side of our history. But “Home Front” makes us long for the future when love, regardless of race or gender or sexuality, will no longer have to suffer the cruel indignities of discrimination.

'Home Front'

Where: The Victory Theatre Centre, 3326 W. Victory Blvd., Burbank

When: 8 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays, 4 p.m. Sundays. Ends Feb. 12.

Tickets: $28

Contact: thevictorytheatrecenter.org or (818) 841-5421

Running time: 2 hours, 15 minutes, including intermission

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.