Review: Was Abraham Lincoln gay? A new play in L.A. imagines his life through a queer lens

- Share via

By way of introduction, Roger Q. Mason, a playwright and performer who uses the pronouns they/them, writes on their website: “I am a Black, Filipinx, plus-sized, gender non-conforming, queer artist of color. My work employs the lens of history to chip away at the cultural biases that divide rather than unite us.”

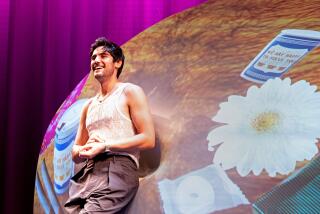

This would serve as excellent description not only of Mason’s character, Taffeta, but also of Mason’s play “Lavender Men,” which is having its world premiere at Skylight Theatre in a handsomely wrought production directed by Lovell Holder. Taffeta, the sparkling emcee of this historical “fantasia” who uses she/her pronouns in the play, employs her queer magic to bring Abraham Lincoln (Pete Ploszek) back from the dead to relive his relationship with a law clerk named Elmer E. Ellsworth (Alex Esola) to whom he’s passionately if discreetly devoted.

The promise Taffeta holds out is that Lincoln and Elmer will get the chance to rewrite their ending. How might history be different if these two men could express their tender feelings for each other? If they could outrun their shame and embrace the love that dared not speak its name in 19th century America or for much of the 20th, for that matter.

Larry Kramer long contended that Lincoln was gay and indeed even wrote about it in his novel “The American People: Volume 1, Search for My Heart.” Mason proudly cuts their own path in this pink-washed tradition.

Here Lincoln is aghast at the over-the-top mannerisms of Taffeta, not understanding why this “fop” has summoned him into a world that no longer follows the old rules of gender, race and sexuality. But Elmer, the object of his obsessive attention, is charmed by Taffeta’s insouciant freedom and so a theatrical game ensues.

Lincoln plays himself before becoming president, when he’s a dourly married attorney in Springfield, Ill., dreaming of a better life for his nation but uncertain of the extent of his ambition or the efficacy of his political talent. Elmer plays himself as an impressive young cadet who, after his dreams of becoming a general are quashed because of his short stature, is educated in Lincoln’s office in the law.

When Elmer asks who Taffeta will play, she replies, “Everything you’re not.” The roles she takes on include Mary Todd Lincoln, a Black office maid and a chandelier. But Taffeta is always within sight, resisting the whitewashing of the historical record, remembering Lincoln’s half-baked idea of sending formerly enslaved people to Africa after the end of the Civil War (regardless of where they were born), sympathizing with love-starved Mary Todd Lincoln and encouraging the sparks of queer love to burn brightly before it’s too late.

Taffeta is fancifully engaged in historical revisionism, but it’s her own history that is as much at stake as Lincoln’s. As she explains early on to the 16th president, “You are the beginning of a trail of hate that leads to me feeling like nothing.”

These incarnations of Lincoln and Elmer are reshaped by her imagination. Lincoln, famously unattractive, is now a looker who’d be exhaustingly in demand at gay circuit parties. Elmer is reconceived as a “muscle twink.” The adjustments are a way for Taffeta to work out her own feelings about being physically marginalized as a queer person of color whose body doesn’t conform to stereotypical ideals.

“Lavender Men,” unwinding on a set by Stephen Gifford that looks like an antique cabinet of wonders, feels at times like a game in which the caprice of the inventor hasn’t yet settled into a reliable pattern. The playfulness drags in part because Lincoln and Elmer, though sensitively performed by Ploszek and Esola, are rarely permitted moments of autonomous life.

Immured in reticent modesty, Ploszek’s Lincoln seems perpetually on the verge of an erotic catharsis that never quite arrives. Esola’s Elmer gazes delightedly at the prospect of a liberated future while holding fast to the fate that will consign him to an early grave as one of the first notable casualties of the Civil War.

The play, however, is Taffeta’s fantasy. And Taffeta always knows best, even when buffeted by the cruelest of inner voices — the mocking, preying, sadistic remarks of internalized racism, homophobia and fatphobia. How might the story expand if there were a mind to challenge her challenging intellect?

“Lavender Men,” co-produced by the Playwrights’ Arena company, picks up power when it veers into performance art and Mason theatricalizes the character’s visceral self-hatred. At one point, reeling from rejection, Taffeta drowns her sorrow in an apple pie — the sloppiness of the scene being a keen source of its pathos.

Mason’s rawness isn’t dramatically seamless, but it’s bracing to witness nonetheless. Nothing is held back in what ultimately amounts to a kind of stage exorcism.

A daring theatrical talent is on display at Skylight Theatre. Evoking the mingled visions of Suzan-Lori Parks (“Topdog/Underdog”), Jeremy O. Harris (“Slave Play”) and Michael R. Jackson (“A Strange Loop”), Mason risks the fearless self-exposure of a performance artist like Karen Finley, who similarly puts her own body on the line in her work.

See “Lavender Men” before it closes at Skylight (or online, now that digital performances are underway) if you’d like to experience an artist on the brink of something fabulous.

'Lavender Men'

Where: Skylight Theatre, 1816½ N. Vermont Ave., L.A.

When: 8:30 p.m. Saturdays, 3 p.m. Sundays, 7:30 p.m. Mondays. Ends Sept. 4.

Tickets: Starts at $20

Contact: (213) 761-7061, lavendermenplayla.com

Running time: 1 hour, 35 minutes

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.