L.A. artist Carole Caroompas, performer and painter who bucked convention, dies at 76

- Share via

Los Angeles artist Carole Caroompas, whose intricate paintings and performances pulled ravenously from pop culture and literature, died July 31 from Alzheimer’s disease. She was 76.

Caroompas’ large, carefully planned paintings riffed on movies, music, literature and current events. They were tapestry-like in their detail but cutting, parodying gender norms and poking at art history — like the time she reimagined Gustave Courbet’s renowned “The Origin of the World,” depicting her own prone female nude as giving birth to a fully uniformed football player.

When she was working in her studio, Caroompas did not worry about where her art might end up. “I’ve never made art for shows; I’ve always just made art,” she said in a 1989 interview, adding that she thought artists had a calling higher, and more interesting, than meeting career milestones. They were “supposed to assault the senses or change the world.”

For the record:

11:26 a.m. Aug. 5, 2022A previous version of this article incorrectly cited the artist as Phyllis Rose, and that Gustave Courbet’s piece is named “The Origin of the Universe.” It has been amended to reflect that her name is Phyllis Green, and that the work is called “The Origin of the World,” respectively.

Her work came before much else in her life. “The art was always her No. 1 focus,” said her brother, John Caroompas. “She didn’t talk about doing much else except working on her artwork,” recalled her friend artist Phyllis Green. “She was always working,” said artist Vincent Ramos, one of her former students who also spent a decade working as her studio assistant.

Over 50 years as a working artist, Caroompas’ imagery and performance art intersected, and informed, multiple weighty 20th century movements: Feminist Art, Pop, Pattern and Decoration, the Pictures Generation. Artist and gallerist Cliff Benjamin, who met Caroompas in the 1980s and later showed her work at his gallery Western Project, found it mystifying that she remained less famous than many of her peers, including Mike Kelley, Chris Burden and Lari Pittman. The decades she spent mentoring the young artists she taught at Immaculate Heart College, Cal State Northridge and Otis College of Art and Design only made the limits of her success more confounding. “She was so influential to legions of kids in art school, legions who were so faithful to her because Carole gave them the real deal,” said Benjamin. “She did not pander. She told them the truth.”

Caroompas was born in Oregon City, Ore., in 1946. She was 8 years old when her family relocated to Southern California, first to San Diego and then to Newport Beach, where her father practiced as a chiropractor and her mother worked in his office. Caroompas spent her years at Newport Beach High frequenting surf-rock shows at Rendezvous Ballroom and then enrolled at Orange Coast College. She took her first art classes there and enjoyed them, but she still chose to major in English once she transferred to Cal State Fullerton.

By the time she graduated from the university in 1968, she had seen her first major museum exhibition — a show of Henri Matisse paintings at LACMA — and knew that she wanted to make art. Her parents found her choice alarming, though they remained supportive, attending her openings throughout their lives (her father, John, died in 1985, while her mother, Dorothy, died in 2002).

Caroompas’ brother John, 11 years her junior, remembers driving up for the opening of a group show she was in, “24 From Los Angeles: New Work by Emerging Artists” at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery on Oct. 30, 1974, the night Muhammad Ali fought George Foreman. He and his dad kept excusing themselves to check the fight’s progress on the car radio. Caroompas’ mother, Dorothy, even sat for a portrait by the artist Don Bachardy, known for his merciless depictions of the city’s creative class. Caroompas kept the portrait hanging beside her studio’s entrance.

Fairy tales, Hawthorne and Zorro inspire recent works by the artist, the subject of a new retrospective.

After college, she enrolled in an MFA program at USC. There, her classmates were mostly men, artist Paul McCarthy among them. “I had to live up to certain male standards of what ‘serious’ art was,” she told the L.A. Times in 1999. Yet as soon as she graduated in 1971, she was swept up in the burgeoning Feminist Art Movement. She joined a consciousness-raising group with Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro and Karen Carson, and sat on the board of the cooperative gallery Womanspace, which opened in 1973. Even in feminist circles, she felt she did not quite fit. At the time, she was making drip paintings, climbing up on a ladder, squirting quick grids of paint onto a wall and then allowing the paint to drop onto a piece of glass below. “They said my work was too formal and not female enough,” Caroompas told the L.A. Times in 1997.

Artist Mary Anna Pomonis, friends with Caroompas since the late 1990s, had a different take. “Judy [Chicago] was talking about creating our own power structures as women and not relying on men for help. Carole was more like, ‘Well, maybe if we get in the room, we can swing the door a little wider and then let more people in,’” Pomonis said. “Rather than trying to burn it down, I think she mocked it, teased it.”

By the mid-1970s, Caroompas had started incorporating more typically feminine materials into her work, still making grids but with glitter, thread and fabric. Then she abandoned abstraction altogether, turning toward collage while embracing pop culture — and comedy — fully. For “Remembrance of Things Past: May” (1976), a dry parody of dating conventions, she lined a piece of paper with gold and black cord and combined slightly maudlin images of a lone high heel and an empty chair with a cursive text, describing a stand-up: “I waited in the bar until 6:30. I had two drinks and a coffee. I thought you weren’t coming.”

For her 1981 performance “Target Practice,” she took on the role of a lecturer exploring archery as an ancient metaphor for desire. Throughout the performance, she would occasionally break into songs she’d composed, including “Bedroom Eyes,” a tongue-in-cheek folk song about a “strong man” taken in by a woman with a “heart of bronze.” She wore black leggings and alligator boots for the performance.

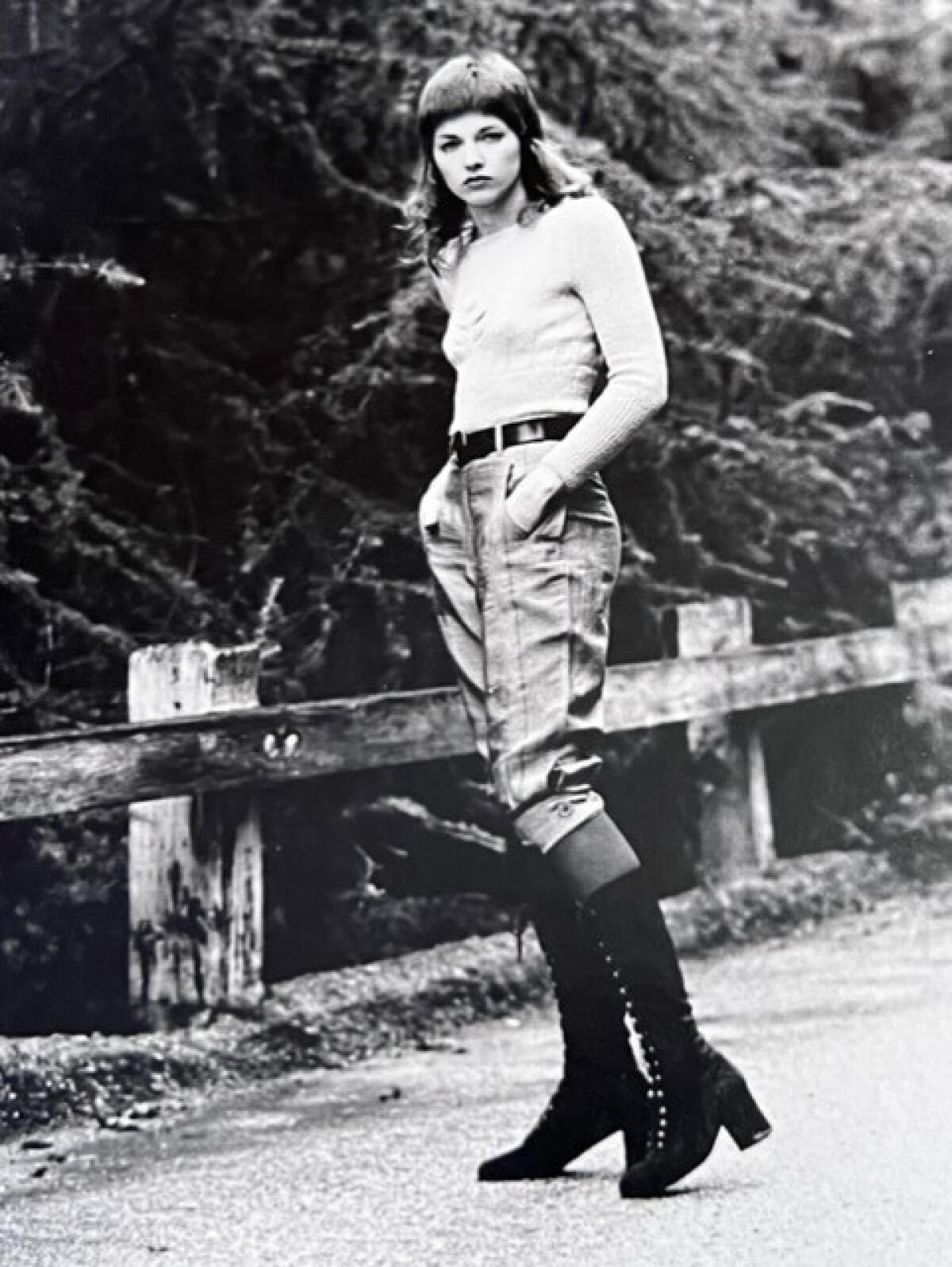

Green noticed Caroompas’ style long before they became friends. Green was at an opening at the Newport Harbor Art Museum and saw “this glamorous babe there in a purple dress, and I thought, ‘Wow, who is that?’” Later, when they both began showing at Jan Baum Gallery on La Brea in the 1980s, it was no longer Caroompas’ aesthetic that impressed Green but rather her work.

Caroompas had transitioned to making epic paintings. She still incorporated found images but no longer collaged them into her work. Instead, she collected, researched her source material, and then painted large-scale scenes that overtly referenced pop and media culture while frequently mining old, iconic literature. In her “Fairy Tales” series, she reimagined “Beauty and the Beast” (1989) as a suburban landscape punctuated by wild animals and businessmen in cages. She bordered the whole scene with black and white male and female figures engaged in a tantric orgy.

These paintings could be a painstaking process. “She invented ways of working that were not necessarily the most practical,” said artist Roy Dowell, her friend and colleague at Otis College of Art and Design, where Dowell founded the graduate program and Caroompas taught from the mid-1980s until early 2020.

While she exhibited her work continuously from the 1970s on, she primarily did so in Southern California, with notable group shows at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in D.C. and the Whitney and Museum of Modern Art in New York. According to curator Michael Duncan, who included Caroompas in his 2012 exhibition about Los Angeles figuration, “L.A. Raw,” at the now-shuttered Pasadena Museum of California Art, “She was one of the most important artists around and has been always underrated and always kind of struggling to get attention because of the toughness of her work.” She was overlooked in the “Helter Skelter” show — an iconic exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 1992 that was largely credited with bringing international attention to a generation of Los Angeles artists who explore perversity, alienation and pop culture — “and there’s hardly any other L.A. artist who fit the parameters of that show so well.”

“Like many women in California, she was considered sort of a local and I don’t think she got her just desserts,” said Green. “She had a real no-prisoners attitude toward her artwork and toward her whole lifestyle.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.