Arts groups raced to be more diverse. How one L.A.-area company tripped along the way

Black artists citing ‘racial tokenism’ quit Long Beach Opera, one of many arts groups nationwide facing scrutiny over their commitment to inclusion.

- Share via

When Long Beach Opera’s executive director and Chief Executive Jennifer Rivera announced James Darrah as the new artistic director of the company in February 2021, she told The Times, “I really did not want to hire a white man for this job.”

“The work of equity, diversity, inclusion and representation is something that has become a core value for me and something I now consider in every decision I make,” she continued, noting there are “very, very, very few opera directors of color, and only a few women.” Rivera said she wanted to work with Darrah to provide more opportunities for artists from underrepresented communities.

But a year later, the company instead stands as a cautionary tale of how diversity efforts can go awry.

Three Black employees, including Long Beach Opera’s associate artistic director and the director of the 2022 season’s opening production, have resigned, citing “racial tokenism” and “a culture of misogyny.” In interviews with The Times, the Black former employees said they were hired and touted publicly as signs of a newly diversified Long Beach Opera, but within the organization — an organization that was supposed to be a collaborative creative effort — they were marginalized by white leadership and ultimately sidelined as artists.

Rivera and Darrah declined multiple interview requests from The Times, and a representative for the company issued a statement that said in part that the company had investigated the allegations and found no evidence of bias.

But a cloud still hangs over Long Beach Opera, one of several companies nationwide grappling with criticism that diversity efforts have been ineffective, poorly executed or downright harmful. Organizations that pledged inclusivity, critics said, have failed to do the hard work of reforming structures built on decades of white supremacy.

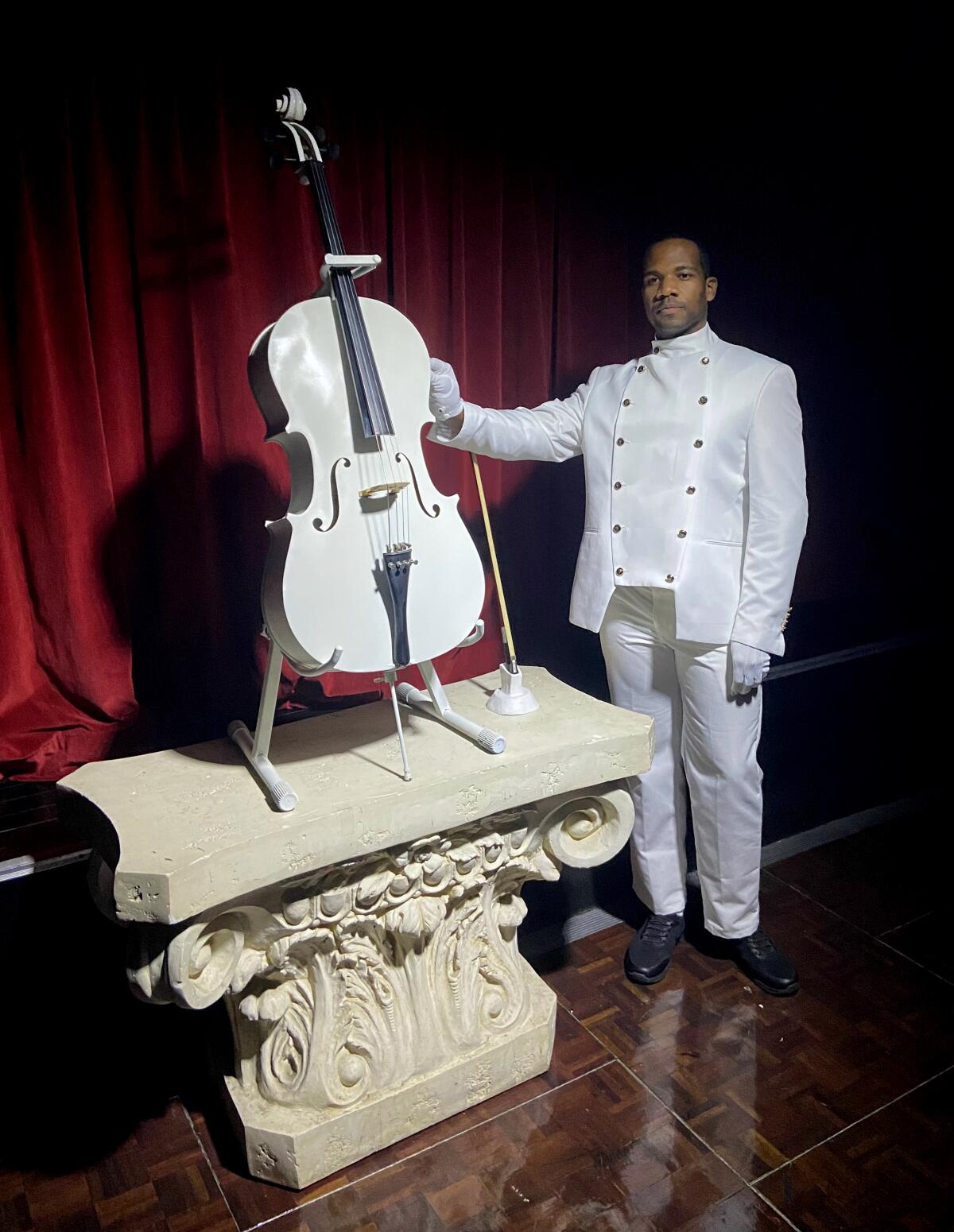

The inaugural event of the Rise Diversity Project gave L. A. high school students a chance to play Hollywood film scores on the Warner Bros. soundstage.

The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 led to a summer of protests calling for social justice and racial equity in every part of society, including America’s stages. Prominent theatermakers of color joined together as signatories of a letter titled “We See You White American Theater,” which pointed out systemic racism in the profession and demanded change. Arts organizations nationwide made public commitments to diversity and inclusion.

In the next two years, many organizations hired artists of color and presented more work centered on the experiences of marginalized people and communities. Over time, however, critics have raised concerns that this commitment was proving to be more performative than profound.

This month at Victory Gardens Theater in Chicago, artistic director Ken-Matt Martin, who is Black, was placed on leave. The move prompted a group of affiliated artists including playwrights and resident directors to resign en masse, citing what they called the board’s inability to support artists of color and its disrespect toward Martin, who allegedly was shut out of important decisions.

In June at San Diego Repertory Theatre, the cast of “The Great Khan,” which consisted mostly of actors of color, issued a statement accusing management “rampant” racism, misogyny, “predatory efforts to take advantage of newly unionized BIPOC creatives,” discrimination and disrespect, among other offenses.

Late last year playwright Dominique Morisseau pulled her play “Paradise Blue” from the Geffen Playhouse just a week after it opened, citing the L.A. theater’s failure to address behind-the-scenes harm to the show’s Black female artists. In a Facebook post, she blamed “the culture of misogyny and abuse that has been allowed to run rampant in our field for generations.”

‘I don’t actually feel welcome here’

Derrell Acon, Long Beach Opera’s former associate artistic director and chief impact officer, joined the company as manager of community engagement and education in 2018, the same year LBO’s longtime artistic director, Andreas Mitisek, announced his intent to resign after the 2020 season.

After being promoted to director of engagement and equity, Acon said he worked hard to make sure the pool of candidates to replace Mitisek as artistic director was as diverse as possible, and Acon eventually put his own hat in the ring. With extensive experience as a performer, producer and administrator, he felt he’d make a good fit.

Around that time, he said, Rivera told him that she was working on a possible merger of Long Beach Opera with Yuval Sharon’s avant-garde L.A. opera company, the Industry. Sharon had recently earned a MacArthur Fellowship and his company was internationally renowned. Such a merger would have been a coup for Long Beach. Acon said Rivera told him that if the merger happened, Sharon would likely be artistic director, but that Acon possibly could be assistant artistic director.

Acon responded by advocating for the new artistic director to be a person of color. “What do we gain by combining two white leadership structures together?” he asked.

The merger did not happen, but in November 2019, LBO announced that it had recruited Sharon as interim artistic director advisor and tasked him with dreaming up the 2021 season.

Three months later, the pandemic struck the United States. LBO paused operations in March 2020, indefinitely postponing the remainder of Mitisek’s final season.

That summer — in the midst of the racial reckoning caused by Floyd’s murder — Alexander Gedeon said Rivera reached out to him, asking if he’d like to be an artist in residence. As part of the deal, he said, Rivera offered that he could design the role to his liking and pick his own title.

Attracted by LBO’s reputation, including its association with Sharon and Acon, Gedeon accepted, eventually becoming the company’s minister of culture. He thought of Sharon and Acon as two of the most articulate, principled artistic leaders in opera.

“The idea that we could be in an engine room together mapping out what the next wave of ethically driven opera looks like just seemed like the most inspiring proposition,” Gedeon said. He had a nagging worry about the company’s motivations for achieving equity and inclusion, but he moved forward.

In the meantime, the hunt for a new artistic director continued. Acon reached the penultimate round of interviews, but in the end the two finalists for the post were white. In hiring Darrah, LBO got a 36-year-old director who had worked with Los Angeles Opera, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Opera Philadelphia and Boston Lyric Opera. He also was a longtime friend of Rivera’s. The two met seven years prior when he directed an Opera Omaha production of Handel’s “Agrippina,” in which Rivera performed the role of Nerone.

A few months later, LBO promoted Acon to associate artistic director and chief impact officer. But Acon and Gedeon said it became clear that the shared leadership model that LBO had promised was a sham. In news articles and on social media, the company touted their positions as part of an artistic collective, Acon and Gedeon said, but behind the scenes LBO excluded them from discussions on major decisions.

Acon said the company has pushed the narrative that he was a disgruntled ex-employee, that “all of my frustration and anger and drama has come out of the fact that I was not chosen as artistic director.” He found this train of thought infuriating, he said, because he remained a loyal employee for almost a year after Darrah was hired.

Gedeon said they were expected to operate largely as a “rubber-stamp committee.” This became glaringly obvious, he said, when in August 2021, LBO hired Wild Up founder and artistic director Christopher Rountree as LBO music director.

Like Sharon, Rountree was a respected national figure in music, distinguishing himself at the Los Angeles Philharmonic and with his own new music ensemble, considered one of the city’s most innovative. Nonetheless, Acon was disappointed that after Rivera’s vocal commitment to inclusion, she was choosing another white man — however qualified — for a top post.

Acon and Gedeon said they already told Darrah and Rivera that the shared leadership model was not working, and that perhaps the company should present a more honest reflection of the organizational structure. Whenever they made uncomfortable points in meetings — questioning plans through the lens of equity and inclusion — they said Rivera would react emotionally and Darrah would shut down. He’d turn off his camera in Zoom, they said, or present his face in profile while remaining silent.

During the first leadership committee meeting, Acon and Gedeon said, Darrah shared his vision for a project that featured all-white collaborators. When they raised their objections, they said Darrah went quiet — refusing to engage in the conversation.

“That was his thing,” Acon said, to, “just shut down in a way where it was actually a source of power.” Acon said that Rivera eventually ended that particular meeting early.

Gedeon came on board with the understanding that he would help to define how diversity and inclusion were translated into the artistic choices. Instead he discovered a disconnect, he said. The company was outwardly celebrating inclusivity while “steadfastly upholding the status quo in every other aspect of production, with the exception of casting.”

The equitable production models Acon and Gedeon created were often siloed off, they said — put into practice within individual projects the two men worked on but not incorporated in any systemic, companywide way.

Alison O’Daniel and Nasreen Alkhateeb are named 2022 Disability Futures Fellows, sharing $1 million with other artists awarded for creative pursuits.

Gedeon said he again suggested to Rivera that the company stop touting its shared leadership model in email blasts featuring Acon and Gedeon’s faces. Gedeon said that when the weekly leadership committee meeting got canceled three weeks in a row, he fired off an email to the group.

“I say, ‘OK, we are now publicly promoting that we have a leadership team. And now we are seriously closing off the avenues of communication. And this is something that I want to address, it needs to be addressed immediately in the next leadership meeting,’” Gedeon said.

When that meeting took place, Gedeon said he reminded the group that he was hired in the wake of summer 2020 and that if “this is turning into a public performance of shared equitable leadership, but we are not in the dialogue … I will absolutely not stand for it. That’s highly unethical.”

He said Rivera and Darrah assured him that things would change.

But after Rountree’s hiring, Acon and Gedeon felt shut out. When Acon asked for Darrah to copy him on important emails, Rivera told him yes and Darrah told him no — that it was unnecessary, Acon said. “It was a constant thing of Jenny saying one thing and James saying something else,” Acon said.

Yuki Izumihara, a former contractor at LBO who worked in design, said it was obvious that Acon was being left out of important email communications and also left off company Slack channels. Izumihara cited an email exchange with Rivera in which Rivera CC’ed Darrah. Izumihara responded by CC’ing Acon, adding, “Let me add Derrell in this conversation. He shares leadership responsibilities with you too.”

“It was not a one-time thing, it was a habit of the company,” Izumihara said of Acon’s exclusion, adding that she has a great deal of respect for Darrah, with whom she is friends and has worked together for years at various companies.

Izumihara said LBO leadership failed to create an inclusive company culture from the top down and described a “difference in temperature when it comes to equity conversations” between Rivera and Darrah on one side and staffers of color on the other.

Gedeon said it was blatantly clear that Acon was being shut out in his role of associate artistic director. “You are minimizing a Black man that you’ve put into a position of power now, very explicitly, and without even an intention of authentically sharing leadership here,” he said, noting the hypocrisy of LBO staging seasons themed on solidarity and justice and hosting parties where guests were invited to meet a diverse leadership team.

“It doesn’t matter how cool the project is that I get to direct next year. I don’t actually feel welcome here. And I don’t actually feel safe, because even when I’m seeing a Black person given power, I’m then watching them precluded from it,” Gedeon said.

When Acon and Gedeon finally issued their resignation letter in December 2021, they said, 10 weeks of staff meetings — 20 meetings total — had been canceled. The men sent another letter to leadership asking for a meeting, and the letter they received in return said in part, “we encourage you to begin working with the mediator immediately so production can continue without delay, and do not believe the group discussion you requested is necessary for work on the production to move forward.”

In other words, Acon said, “We just want you to do to work. … You’re the workers, we’re the decision-makers, so do your thing, and let the big boys behind the scenes have the big conversation.”

These are the 16 must-see works of art from permanent collections at the Huntington, LACMA, the Getty, MOCA, the Norton Simon, UCLA’s Hammer Museum and more.

A week before the 2022 season opening, Acon and Gedeon felt they simply could not continue. They left the company for good, along with engagement and education coordinator Elijah Cineas.

With Gedeon gone as director of the season’s first production, LBO hastily canceled “Stimmung,” scheduled to open March 18 in an abandoned grocery store in Long Beach. The production was to unfold in a “magical kitchen” as six performers prepared a meal at a central table surrounded by the audience, with whom performers would share the food.

LBO also canceled its second presentation of the season, the show and film “Quando,” after Acon (the show’s producer) and director Tee Vaden pulled out.

Long Beach Opera’s board hired an investigator, Aisha Shelton Adam, to look into the complaints of 10 employees, including Acon, Gedeon and two undisclosed staff members — one a person of color, one a woman. (In an interview with The Times, the woman — who requested anonymity because she worried about professional repercussions for speaking out — cited examples of what she called LBO’s culture of misogyny.) The company hired a human resources firm as well as a mediator, who met with members of the artistic staff.

The company’s statement to The Times said Shelton Adam found no evidence of gender or racial bias. In declining further comment, the company said: “While a great deal of the allegations listed here are extremely misleading, lacking in important context, simply false, or contain direct personal attacks, we feel that as an organization, continuing to publicly engage with the complaints of former employees is causing undue harm to our current employees and artists.”

Have Black artists been lifted up? Or pit against one another?

The LBO resignations were at odds with the reputation of the 42-year-old company that in June 2019 premiered “The Central Park Five,” which explored the wrongful rape conviction of a group of young Black men. Its composer, Anthony Davis, went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for music.

Davis said that as a Black artist, his experience with the company, and with Rivera in particular, have been very positive. He added that LBO “has been one of the strongest advocates for paying composers of color and supporting our work.”

Davis said Acon and Gedeon undercut a production of “The Central Park Five” staged this last June. After initial media coverage of Gedeon’s and Acon’s resignations, “The Central Park Five” director, stage manager, set designer, costume designer and projection designer, as well as several performers, all pulled out of the project. New artists signed on, however, and the show bowed to solid reviews.

“I thought there were efforts on their part to undermine the project. And I felt that that was misplaced,” Davis said. “And I felt that was destructive in terms of the bigger picture of what we want to accomplish in terms of people of color in opera — in trying to create an environment in opera that’s positive and productive.”

Davis said he doesn’t know firsthand what Acon and Gedeon experienced as staff members at LBO. “My question is whether it rises to being an endemic thing in terms of the opera company, or whether it’s a personal grudge, a personal problem,” he said.

Gedeon’s response: “It’s important to recognize that Mr. Davis is a trailblazer in this industry, whose legacy is still crystallizing. I think if you imagine a movie studio in which a celebrated screenwriter had a wonderful experience, one wouldn’t extrapolate that all studio employees were free from mistreatment, or that the executive structure didn’t have major issues.”

Shelley Washington, a young Black composer and saxophonist, who worked on LBO projects including Acon’s “Quando,” echoed Davis’ feelings about being supported and lifted up by the company. After Acon and Gedeon’s resignation, the company admitted its failures and is doing the necessary work to change, she said in a phone interview, noting that she is excited to continue her work with the company.

In a subsequent email, Washington wrote: “I recognize that my experience is much different than those who worked with them in office full time in administrative or creative roles. My intent is not to discredit the personage or invalidate the feelings of Derrell, Alexander, or anyone else involved. This is my perspective based on personal experience and observations.”

Washington added her concern that the dispute could serve to pit historically marginalized people against one another. Acon and Gedeon share that fear, adding that LBO’s limited public comment along with its use of Davis and Washington as defenders has done just that. Acon called it a familiar and “abhorrent” tactic to “pit Black people against other Black people to protect white structures.”

Gedeon pointed out that LBO never released the contents of its investigation, only the findings.

“They have the luxury,” he said, “of writing the jacket blurb for a book nobody else gets to read.”

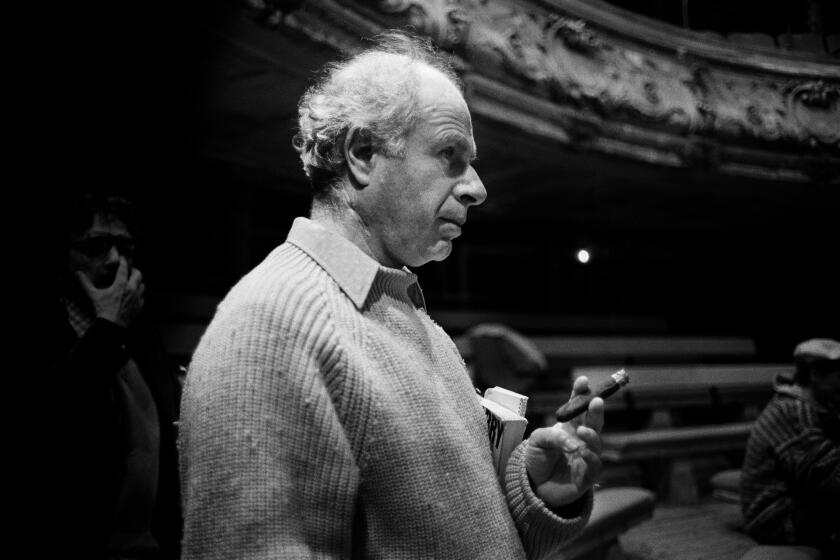

The famed director Peter Brook and noted musicologist Richard Taruskin, who died a day apart, are diametrically opposed forces of how we think about performance.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.