Commentary: A stolen, horribly damaged De Kooning painting gets the Getty conservation treatment

- Share via

The ripping sound must have been horrific.

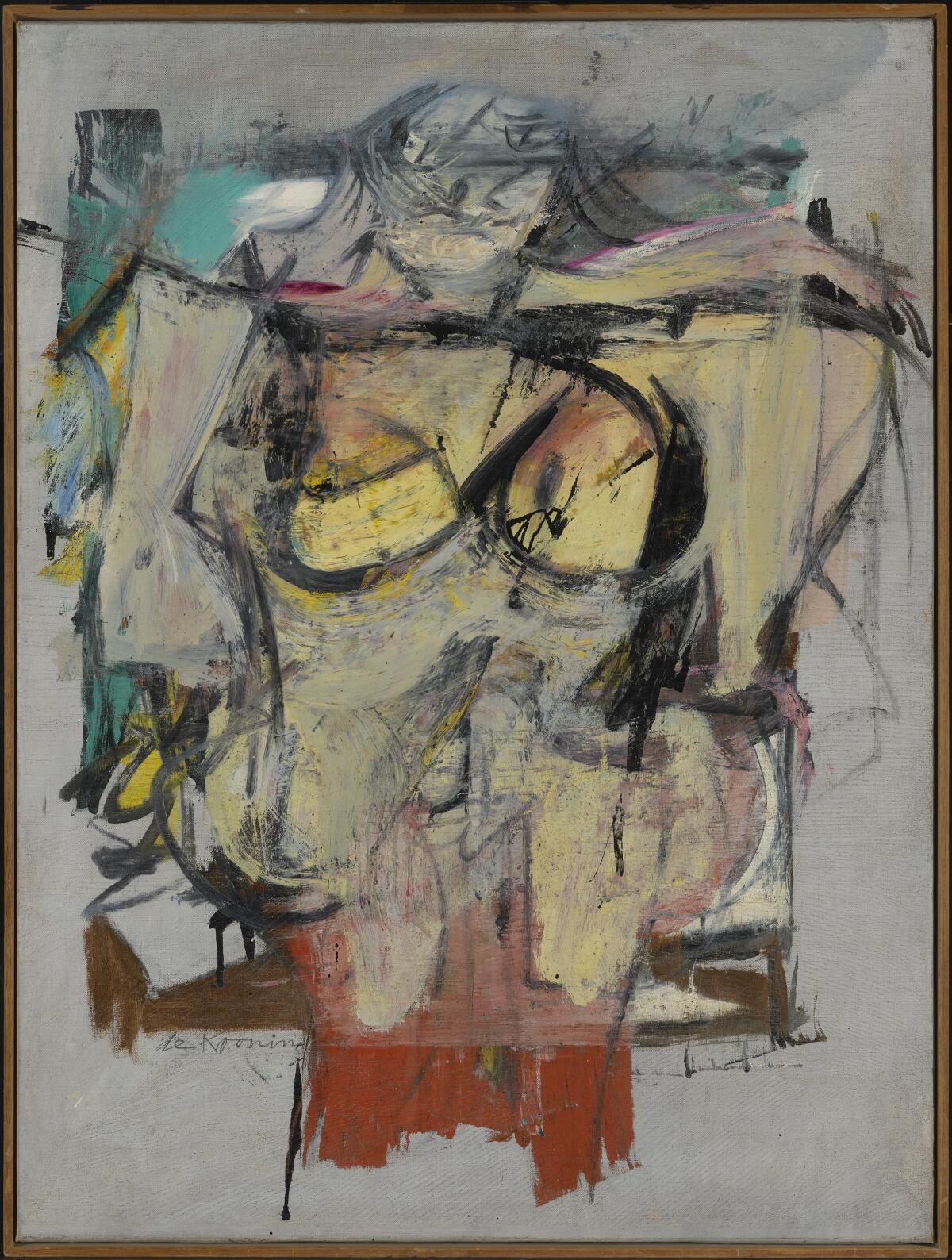

When thieves pulled out a sharp blade to slice Willem de Kooning’s painting “Woman-Ochre” from its frame at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson in a daring, daylight heist on the day after Thanksgiving in 1985, they likely expected the canvas to fall out into their waiting arms like a silk scarf slipping off bare shoulders.

But it didn’t.

The wildly satirical painting of a ferocious, naked, imperiously enthroned woman pretty much stayed in place. Unknown to the crooks, the fine linen on which De Kooning painted in 1954 and 1955 had been attached to a second backing during a 1974 conservation treatment at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. There were two canvas layers, not one.

MOMA conservators, using a procedure then not uncommon, had affixed a new lining infused with warm wax to the back of De Kooning’s canvas, about 40 inches high and 30 inches wide, bonding the lining with the painting on top. To cut through the second layer, the thieves’ blade needed to go deeper. It didn’t, and the painting stuck. So, while one thief kept a lone museum guard distracted, the other took hold of the painting at the top left corner and, yanking it down toward the right and then pulling it sharply to the left, violently ripped it off the intractable backing.

Rrrrr-ip!

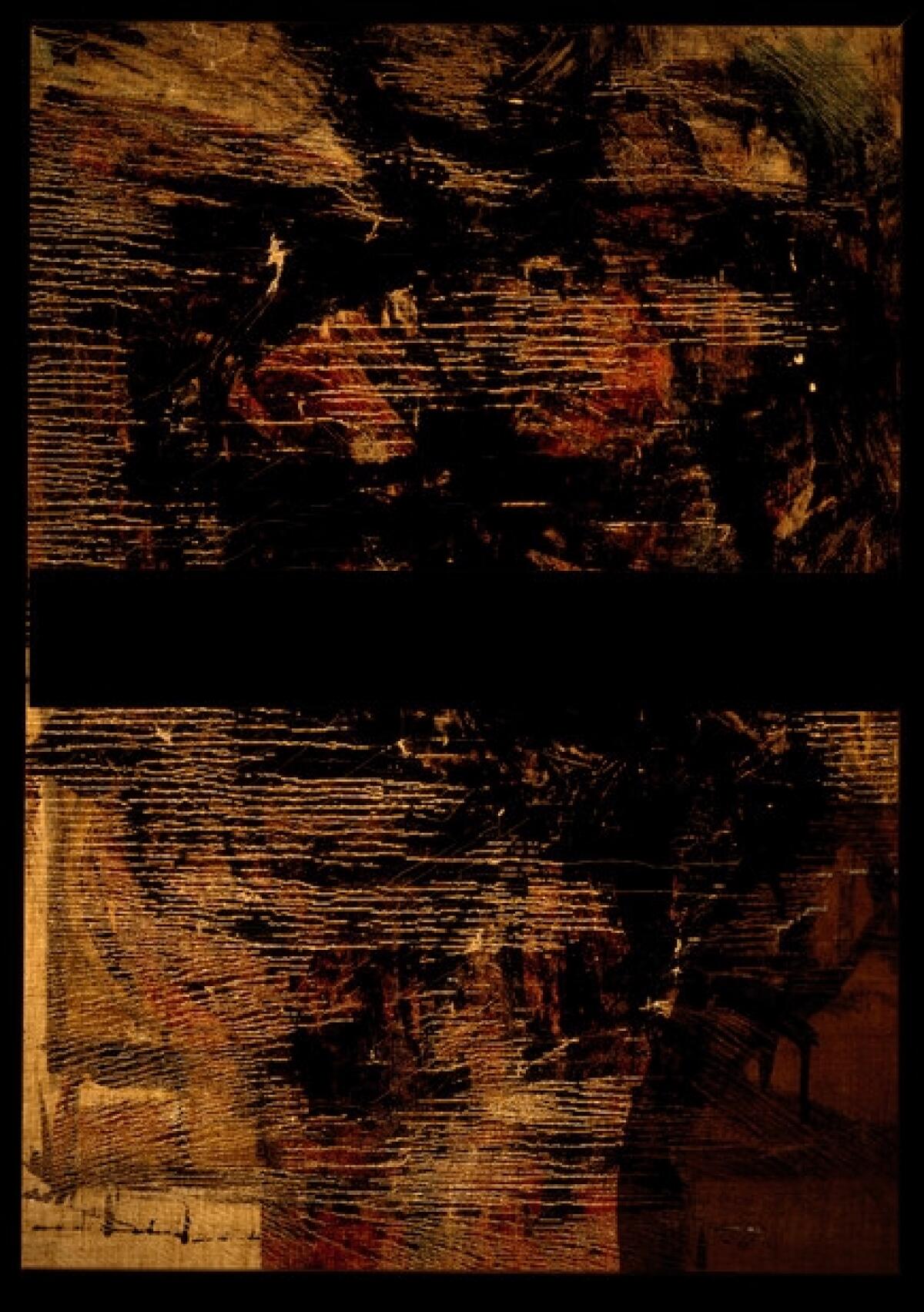

As the two canvas layers pulled apart, hundreds of fine, jagged, horizontal cracks piled up, one atop the other across the paint surface. The hairline cracks especially damaged the fearsome woman’s shoulder, arm and full breast along the right side of the canvas, while more thinly painted areas of the spatial background shattered. The intensity of the ripping action also likely caused the nasty, ragged tear, several inches wide, that turned up just below the woman’s left arm, as well as a few smaller ones farther down — one just below De Kooning’s signature.

When I first saw the terribly damaged painting in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s conservation studio nearly three years ago, my eyes bugged out. Lying flat on a table, sort of like a corpse, it was a mess. The canvas was as rumpled as last night’s sheets — a lumpy terrain whose painted image was lost in a visual muck of disheveled paint marks, yellowed varnish and all that awful, crackled damage.

Senior paintings conservator Ulrich Birkmaier lifted the canvas up and held it before a studio window, where backlighting streamed through all the surface tears, large and small. They looked like the long, horizontally traveling flashes of spider lightning in the night sky during a summertime electrical storm on the prairie.

“That painting is dead,” I moaned to a friend I had telephoned as I drove down from the Getty’s hill. “It’s such a ruin, they’ll never be able to fix it.”

I was wrong. After a couple painstaking years of conservation work, interrupted but undeterred by the COVID-19 pandemic, she’s back.

“Woman-Ochre” is not perfect — how could it be, given the shocking assault? — but conservators have returned the painting to a state of remarkable cohesion. Some scars from its traumatic biography remain quietly visible, but you need to look closely to see them. At a normal viewing distance, they’re hardly visible.

The second time I saw “Woman-Ochre,” earlier this year, the surface plane was flat, the brushstrokes clear, the toothy, glowering figure with pendulous breasts and thick, sturdy limbs had emerged from the gloom. Last week, on my third visit, as Birkmaier, fellow conservator Laura Rivers and Getty Conservation Institute scientist Tom Learner were making final preparations for the June 7 unveiling of a new show about the ambitious, multiyear recovery process, I was nearly as surprised as I was the first time — albeit in a very different way.

Now, De Kooning’s woman is an energetic body, a commanding figure with visual weight and fleshy mass seated in three-dimensional optical space. (“Flesh is the reason why oil painting was invented,” the artist famously said not long before launching the contentious “Woman” series in 1950.) Pigmented areas of brushy red, yellow, blue and secondary colors blossom within a grayish, atmospheric field dominated by rapid strokes of black line. It’s as if she’s been carved like an archetypal totem, but with matte and glossy house paint, charcoal and oil paint on canvas rather than with a chisel or an adze from stone or wood. “Woman-Ochre” approaches what De Kooning originally made.

What drove the thieves to do their gruesome deed might have been an authentic urge to be close to that marvelous painterly phenomenon — a product of one of the greatest artistic talents of the Modern era and part of a controversial series that secured De Kooning’s reputation. Fencing it for cash was not the thieves’ plan.

Instead, when the contents of a house in remote Cliff, N.M., — a three-hour drive east of Tucson into the northern reaches of the Chihuahuan Desert, population about 175 — were sold to a used furniture and antiques dealer in 2017, the painting was found hanging out of public view, hidden behind the main bedroom’s door. Furniture dealer David Van Auker didn’t know what it was, and there was no one to ask. Homeowner Rita Alter had just died, her late husband Jerry had been gone for five years, and neither of the two retired public school teachers — both New York City ex-pats — left any explanation. Van Auker loaded the picture into his truck with the Alters’ other stuff, having agreed to pay $2,000 for the lot of it, and drove off.

Thirty miles down U.S. 180 in his Silver City shop, he propped the disheveled painting up against a chest. Not long after, a local artist happened in, took a long look, and exclaimed that it seemed like an actual De Kooning. Van Auker later Googled, and up popped news stories of the 1985 theft of a painting in the state next door with an insurance value of $400,000. (Last year, a “Woman” painting on paper from the same moment and just 1/3 the size sold for $8.5 million.) The photo reproduced in the stories matched the painting in his store. He called the University of Arizona Museum of Art about his discovery, and within 36 hours a curator was at his doorstep.

The FBI opened an investigation and, although nothing definitive has yet been decided, it seems pretty certain the Alters were the thieves. (“The Thief Collector,” a new documentary film by Allison Otto on the heist, suggests the couple may also have lifted a Frederic Remington bronze and a million-dollar Native American chief’s blanket, the latter from the Amerind Museum an hour outside Tucson in Dragoon, Ariz.) The tale of the treacherous theft of a masterpiece and its almost accidental recovery is wild, but so is the extraordinary conservation outcome.

The late-November morning of the theft was chilly, in the low 50s with a light breeze, when a bundled-up man and woman entered the two-story Arizona museum shortly after it opened. It was quiet, unsurprising for a long weekend with students on holiday and professional staff largely absent. When the pair fled 15 minutes later with the painting rolled, crumpled and stuffed under a coat, that was the last time its whereabouts were known for the next 32 years.

Reasonable assumptions were that the rolling and stuffing had caused the bulk of the damage, but conservators soon learned otherwise. The fused double-canvas had in some ways been a bigger culprit. The thieves had also made crude attempts at restoration, touching up their prized De Kooning with mismatched paint. They folded and stapled the sliced canvas edges over a cheap new wooden stretcher, shrinking the size of the picture by several inches all the way around and changing the figure-ground relationship. The GCI’s Learner used sophisticated X-ray imaging techniques to determine paint chemistry and survey damage less visible to the naked eye.

Rivers, the paintings conservator, began reattaching hundreds of loosened paint fragments, each no larger than a peppercorn, using a microscope and the type of tools you expect at a dentist’s office. Ironically, the 1974 varnishing and warm wax relining had helped keep the surface paint in place when the violent ripping happened. They produced a seal — a kind of sandwich with the paint held in between.

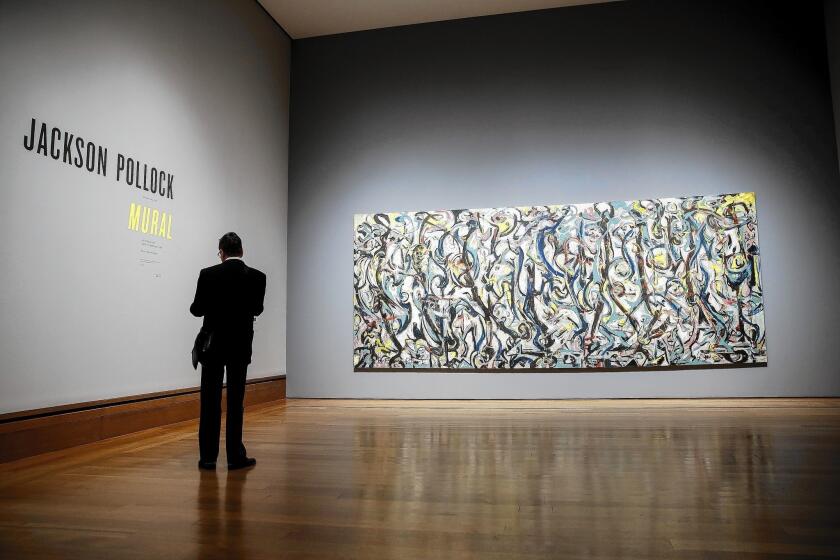

Rebirth of Jackson Pollock’s ‘Mural’

Other tiny flakes of paint stuck in the varnish were saved in an ordinary plastic storage box, the kind a hobbyist uses for fishing lures, beads or screws. Each small compartment was numbered to correspond to a gridded map showing where it came from on the painting’s surface. Some flakes were analyzed to determine their composition, enhancing extensive GCI research published in Susan F. Lake’s 2010 handbook, “Willem de Kooning: The Artist’s Materials.” The meticulous book, a systematic study of his painting process, was one reason the Getty volunteered its services free of charge to the Tucson museum when the discovery story broke. It helped guide the current conservation.

Next, Rivers began the laborious, centimeter-by-centimeter process of removing yellowed varnish — not once, but twice. One varnish layer was professionally applied during the MOMA conservation, undertaken after the painting was punctured near the fiendishly glaring face during a visit to MAMBO — the Museo de Arte Moderno in Bogotá, Colombia — in June 1974. (The exhibition, “Four Contemporary Masters: Bacon, Dubuffet, Giacometti, De Kooning,” was part of the New York museum’s extensive program of traveling shows sponsored by its International Council, originally subsidized by the CIA as Cold War advocacy.) Another, clumsier layer of cheap varnish was no doubt applied by the thieves.

After the heist, the museum had kept the original stretcher, the wax-infused lining and the ribbons of canvas that had been cut off. At the Getty, those canvas strips were slowly, gently flattened on a warming table, just as the full canvas had been, and the painting then fitted inside. On the back, the pieces were re-joined with a narrow strip-lining around all four edges, and a new stretcher was built for the restored canvas plane. Birkmaier began the arduous process of inpainting the tiny cracks, the joined places around the perimeter, the repaired tears and the rough puncture marks from the stapling. De Kooning’s complex palette was matched with Gamblin Conservation Colors, a stable, easily reversible paint.

The painting had been donated to the University of Arizona museum in 1958 by wealthy Baltimore businessman Edward J. Gallagher Jr., a Sunday painter who vacationed in the area. (His other notable gifts included New York School paintings by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Franz Kline.) When it returns to Tucson in the fall, after the Getty exhibition, “Woman-Ochre” will return to being its troublesome self — a picture loaded with sexual anxiety.

Like the others in the “Woman” series, the painting might represent a female idol at once sensual and ghastly, which some have caricatured as misogynist. Others recognize the confrontational complexity of art embodied as a multifaceted relationship, with furious calligraphy and caressing brushstrokes used to announce the singular, conflicted presence of the artist — and, by extension, the actively engaged viewer. Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, De Kooning’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biographers, observantly described the “Woman” series as “no better suggestion in art of a tantrum, no truer rendering of the child who knows only that he wants — and is desolate — as he hurls himself back and forth against an unyielding strength.” Now out from private hibernation behind a bedroom closet door in the desert and back from a public state of ruin, the vivifying struggle recommences for “Woman-Ochre.”

'Conserving de Kooning: Theft and Recovery'

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Dr., (310) 440-6810

When: Tuesdays-Sundays 10am–5:30pm. Closed Mondays. June 7–August 28

Info: www.getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.