- Share via

DENVER — Though he may be renowned for lobbing vulgar insults, the barb that Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva directed at Supervisor Hilda Solis in July 2020 left even longtime observers stunned. Solís had made comments critical of systemic racism by police toward people of color. “Are you trying,” Villanueva said in a Facebook post addressing Solis in one of his regular online broadcasts, “to earn the title of a La Malinche?”

The comment left many people — including me — ice cold, since to deploy Malinche’s name as an insult is to parrot a gross misogynist trope.

Malinche, the Indigenous girl who served as interpreter to Hernán Cortés in the early days of the Spanish invasion of Mexico — and who was, for all intents and purposes, enslaved by him — has long been deployed as a symbol of betrayal in Mexico. Indeed, she’s been cited as the figure on whom responsibility for the fall of the Aztec empire is often heaped. Never mind that colonization occurred as part of a confluence of factors that included conflict between warring city-states and the unchecked spread of European diseases. Centuries out, Malinche carries the blame.

After Villanueva’s tirade, Solis, the only Latina member of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, described the sheriff’s statements as “inappropriate, racist and sexist.” Villanueva never apologized for the remarks.

This grotesque incident appears in an exhibition catalog for “Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche,” a show at the Denver Art Museum that concludes May 8. Co-curated by Victoria I. Lyall of the Denver Art Museum, independent curator Terezita Romo and Matthew H. Robb of UCLA’s Fowler Museum, this groundbreaking show gives thorough reconsideration to a figure who played a critical political role as interpreter but who left no direct record of her words and her person.

“As a result of these ambiguities,” write the curators in the catalog, “historians, artists, writers and politicians have been free to project their own agendas to her.”

Those agendas have been extensive and they have evolved in elaborate ways over time.

Culture in plague times: The Florentine Codex, an encyclopedia on Mesoamerican indigenous life, was created as Mexico was ravaged by smallpox

Born around 1500, Malinche entered the Western historical record in 1520 when Cortés, in a letter to the Spanish crown, described her as “mi lengua” — literally, “my tongue,” his translator — without mentioning her name. Following that, she appears in 16th century chronicles, most of them written and illustrated in the decades after her death, the date and exact cause of which is uncertain. (Historians believe she had died by 1530.)

Malinche is a regular in these colonial documents. Rutgers University historian Camilla Townsend reports in an illuminating exhibition catalog essay about the ways in which depictions of Malinche evolved over the course of the 16th century. Of the estimated two dozen Indigenous chronicles related to the conquest that survive in library collections, Malinche appears in nine. In some early annals, she is described as Marina, her Spanish name; in others, she appears as Malintzin, with “-tzin,” an Indigenous Nahua honorific, attached to her name. Today, throughout Mexico, as well as in much of the rest of the continent, she is primarily known as La Malinche, the Malinche — the article conveying her singular status in the context of Mexican history.

Yet, despite her outsize presence, we have only the most basic contours of her life.

In his memoirs, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Cortés’ soldiers, reported that Malinche was from Coatzacoalcos, a coastal settlement in present-day Veracruz, and that her family sold her as a child to Indigenous traders who then turned around and sold her to the Chontal Maya. Townsend, who in 2006 published “Malintzin’s Choices: An Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico,” has called into question whether Malinche was sold off by her own family, however, noting that she was more likely to have been taken.

Whatever the exact chain of events, Malinche’s odyssey into slavery meant that by the time the Spanish arrived, she was fluent in two languages: Maya and Nahua (the language spoken by a combination of groups broadly identified as Aztecs). This helped make her one of Cortés’ most vital diplomatic assets.

How exactly Malinche ended up in the hands of the Spanish is also up for debate. But she was young when it happened, likely between 11 and 16 years of age.

In the latest flare-up in his feud with county officials, Sheriff Alex Villanueva refers to Supervisor Hilda Solis as “La Malinche,” a name historically used in Mexico to demean a woman as a traitor or sellout.

The Denver Art Museum’s exhibition charts the ways in which the narratives that surround Malinche have evolved. She was an Indigenous girl who, through no choice of her own, found herself at the center of historic events, only to later have her role in those events marginalized by both artists and historians. Over the years, her profile has been resuscitated in various guises: as Eve to the modern Mexican nation, as a traitor on whose shoulders lay the devastating legacies of colonialism, as a figure of reclaimed feminist histories.

It’s a lot for a woman whose own voice remains muted by the vagaries of history.

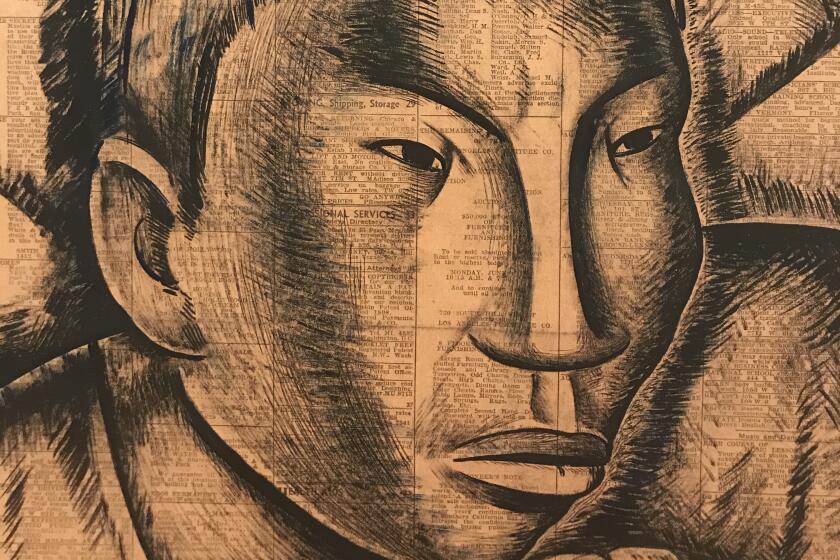

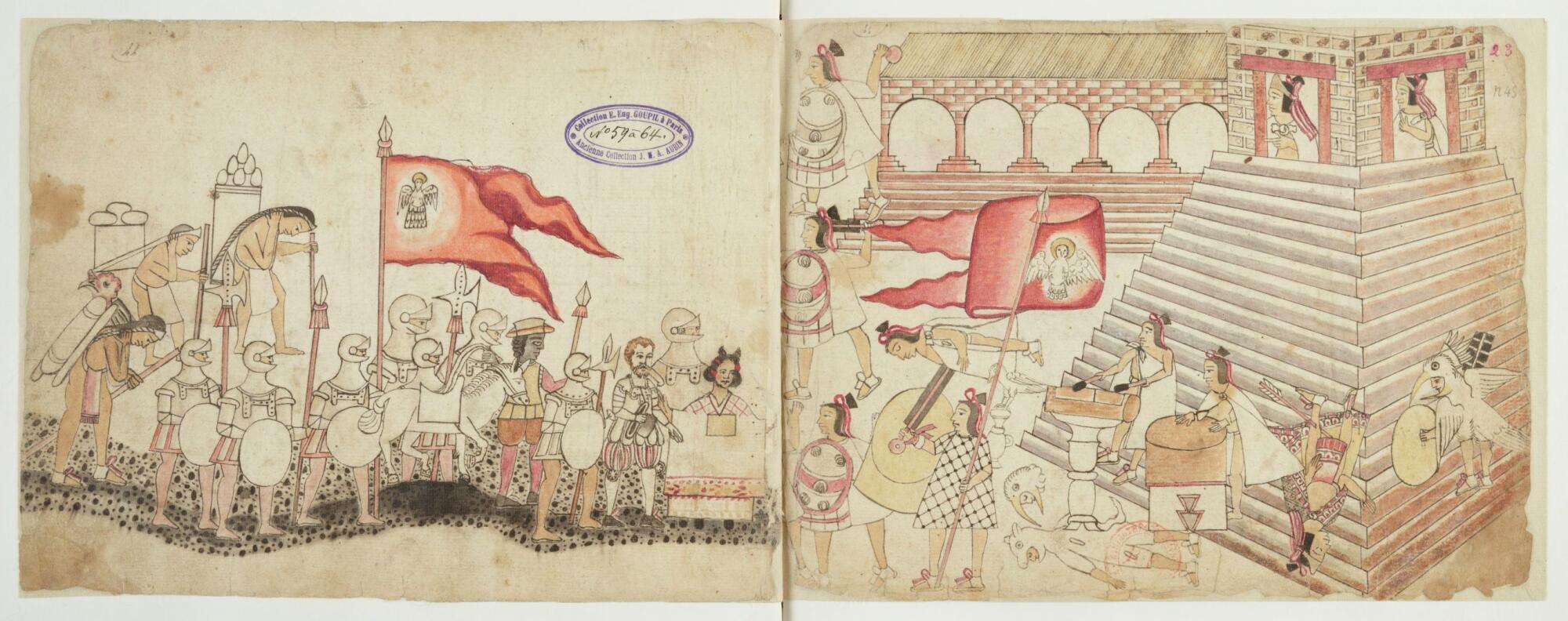

While “Traitor, Survivor, Icon” is thematic, the exhibition does follow a rough chronology based on the way her image has been remade over the centuries. The first three sections feature some of the surviving scraps of historical documentation from the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century. Malinche materializes in colonial annals and historic reproductions of the famed “Lienzo de Tlaxcala,” a 1550s codex that recounted the Spanish invasion from the point of view of the Tlaxcalans, a group that was hostile to the Aztecs.

In some of these colonial illustrations, Malinche’s hair is shown loose, in the style of an unmarried woman, in others, it is bound, marking that she was wed. (After giving birth to a child by Cortés, whom they named Martín, Malinche married Spanish soldier Juan Jaramillo in 1525 and had a daughter, María.) She frequently wears a huipil, the loose woven blouse worn by Indigenous women; on one occasion, she is shown bearing a shield.

Often, she is central to the action, standing between or just behind Spanish and Indigenous leaders.

The first section of the exhibition focuses on Malinche’s role as intermediary — an installation that, taken in concert with the show’s excellent catalog — makes the point that Malinche was a translator not just of language, but of customs and points of view.

Translation is more art than science, and when doing so, you don’t simply interpret words as they are spoken, you also interpret for how they might be received. As Townsend notes in her catalog essay, Malinche was a figure who served as a “voice of reason, the one who understood and articulated the traditional chiefly duty of saving as many lives as possible in order to preserve the future.”

Throughout the show, historic pieces commingle with contemporary works that reflect on the figure of Malinche and the myths that surround her. This includes a compulsively watchable ‘80s-era video performance by Mexican artist Jesusa Rodríguez, “La Conquista según la Malinche,” which purports to report the conquest from Malinche’s point of view.

The Whitney Museum exhibition “Vida Americana” shows that to admire 20th century American painting is to admire its Mexican influences on artists such as Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, Jacob Lawrence and Charles White.

The six-minute video shows Rodriguez dressed up as Malinche, standing atop a partially buried pyramid at Cuicuilco with a series of anonymous-looking apartment towers as backdrop. Here, she delivers a humorous broadcast detailing the fateful encounter between the Spanish and Moctezuma, while also skewering corruption within the modern Mexican government.

With its casual delivery and its deft use of slang, Rodríguez’s piece is a tour de force of wordplay and innuendo, one that seems to borrow stylistically from fast-talking Mexican comedian Cantinflas. She conflates terms for historical colonial figures with Mexico’s public housing agency. She launches barbs at Henry Kissinger and Mexican media mogul Emilio Azcárraga. She tells the story of colonization as if she were relating a messy night out over a bucket of beers.

Throughout, she plays with various conjugations of the word “say” — “What’d he say?” “What am I supposed to say?” “Well, I’m just saying.” — as if to indicate that in the end, all we have of Malinche is hearsay, and that what Malinche herself may have said may have been out of an instinct for self-preservation or a mischievous attempt to throw rocks into the gears of colonization. It is devastating and brilliant.

The exhibition’s subsequent sections highlight the ways in which Malinche’s indigeneity has been both deployed and erased, how the figure who was central to many colonial chronicles was, over time, relegated to bit player, and when she did reemerge, it was in romanticized ways.

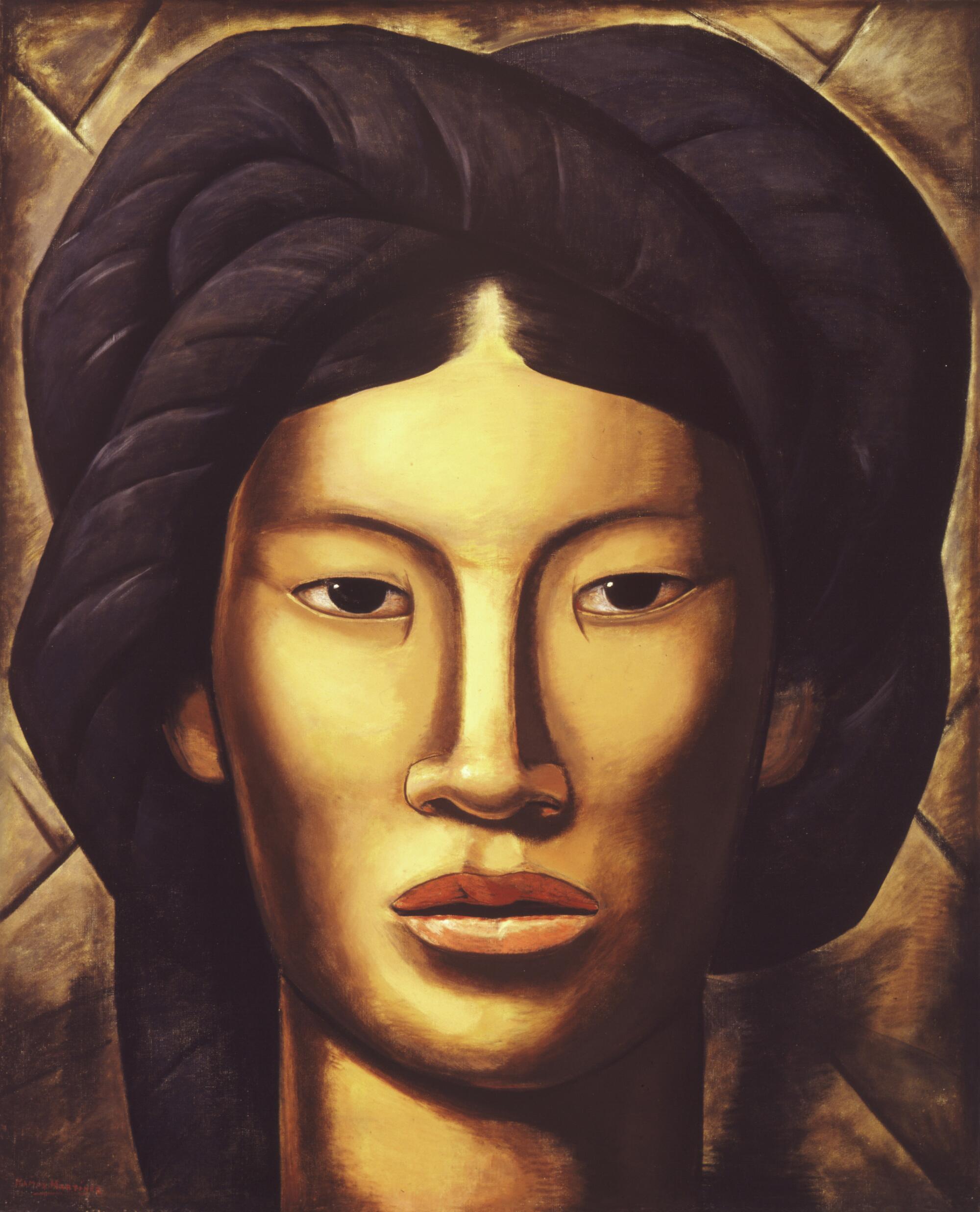

Particularly striking is Alfredo Ramos Martínez’s 1940 painting, “La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca),” in which the luminous yet impassive face of an Indigenous woman meets the viewer’s gaze. It’s a work that takes the abstracted concept of Malinche and makes her flesh and blood — a real person whose eyes convey turmoil and defiance.

A startling counterpoint is a 1941 painting created by Mexican artist Jesús Helguera, who was known for his melodramatic canvases of Aztec warriors and maidens, images that were frequently reproduced on giveaway calendars. In “La Malinche,” Helguera renders a Malinche with light skin and European features looking like a cinematic bombshell à la Dolores Del Río. She is shown atop a powerful white horse, nestling into Cortés’ arms, a flirty hand grazing her exposed neck.

It is Malinche as sultry ensnarer, a painting that renders a woman who was enslaved into willing seductress — a reminder that the story of Malinche is one that has most frequently been told by men.

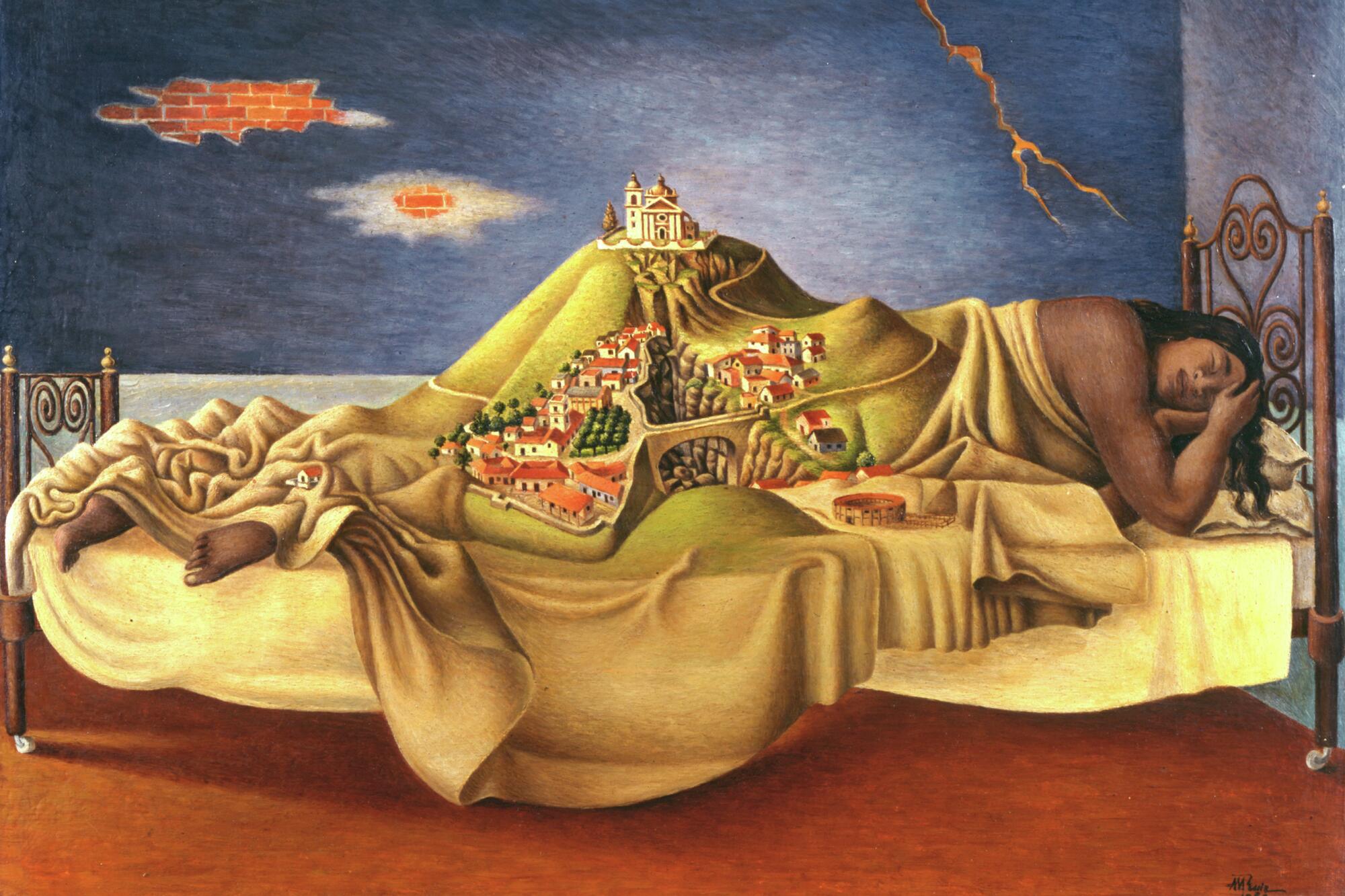

If romantics such as Helguera transformed Malinche into willing participant, the Mexican Revolution of 1910 put her in the cultural crosshairs. By the early 1900s, Malinche was being portrayed as the mother of mestizaje (a term that typically refers to the mix of Spanish and Indigenous blood). In this way, she becomes the symbolic mother of the Mexican nation, with her son Martín embodying the first mestizo.

In art, Malinche begins to be shown as Eve to Cortés’ Adam, with all the implications of treachery that this biblical metaphor evokes. These themes materialize in murals by Diego Rivera, Jorge González Camarena and José Clemente Orozco, who in a 1926 mural for the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City depicted Cortés and Malinche as nudes.

It’s a truly disconcerting work (which the exhibition’s curators have reproduced as a wall-sized vinyl). She is expressionless, and their hands are clasped — more in the style of a handshake than in affectionate embrace. He also blocks her body with his extended left arm, his foot resting on the body of a man, presumably Indigenous.

In post-revolution Mexico, a moment of intense nationalism, in which intellectuals and artists were rejecting the European in favor of the Mexican, to be revolutionary was to disavow the Spanish Conquest and the subsequent colonial period, writes Luis Vargas Santiago, an art historian at Mexico’s National Autonomous University, in his contribution to the catalog. Malinche, therefore, “was established as the origin of the mestizo shame, that imperfect stain or original sin the revolution came to erase.”

The idea of betrayal was further cemented by prominent writers such as Mexican Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz. In his influential 1985 essay, “Los hijos de la Malinche,” he casts her as a tragic figure — a symbol of violation — but a violation in which she played an active role. “It is true,” writes Paz, “that she gave herself voluntarily to the conquistador, but he forgot her as soon as her usefulness was over.”

By the end of the 20th century, the story of Malinche was the story of a traitor, to be a malinchista was to act against the interests of your people.

When the late Mexican architect Carlos Lazo began planning work on the behemoth Mexico City headquarters for the country’s Ministry of Communications and Public Works in the early 1950s, he told the artists creating murals for its exterior to be guided by one principle: The Centro SCOP, as the complex is known in Spanish, should be “a work that lasts.”

The Denver show goes deep on this topic, showing a number of works that touch on the idea of Malinche as traitor. But where the exhibition truly breaks ground is in revealing the ways in which Malinche’s reputation has been reclaimed over the last four decades by feminists, most notably by Chicana artists from the Southwestern United States.

In a photographic work from 1993, New Mexico-based artist Delilah Montoya depicts her as a girl dressed up for her First Communion — her white dress symbolizing purity, with the Christian symbols and the title of the work, “La Malinche,” acting as harbingers of what is to come. In another poignant piece, Arizona artist Annie Lopez took vintage photos of women in her family and inscribed them with texts such as “sold as slave” and “interpreter and companion,” adding a layer of historical darkness to images of a young woman posing ebulliently for the camera. It’s a work that seems to say, this could be any of us.

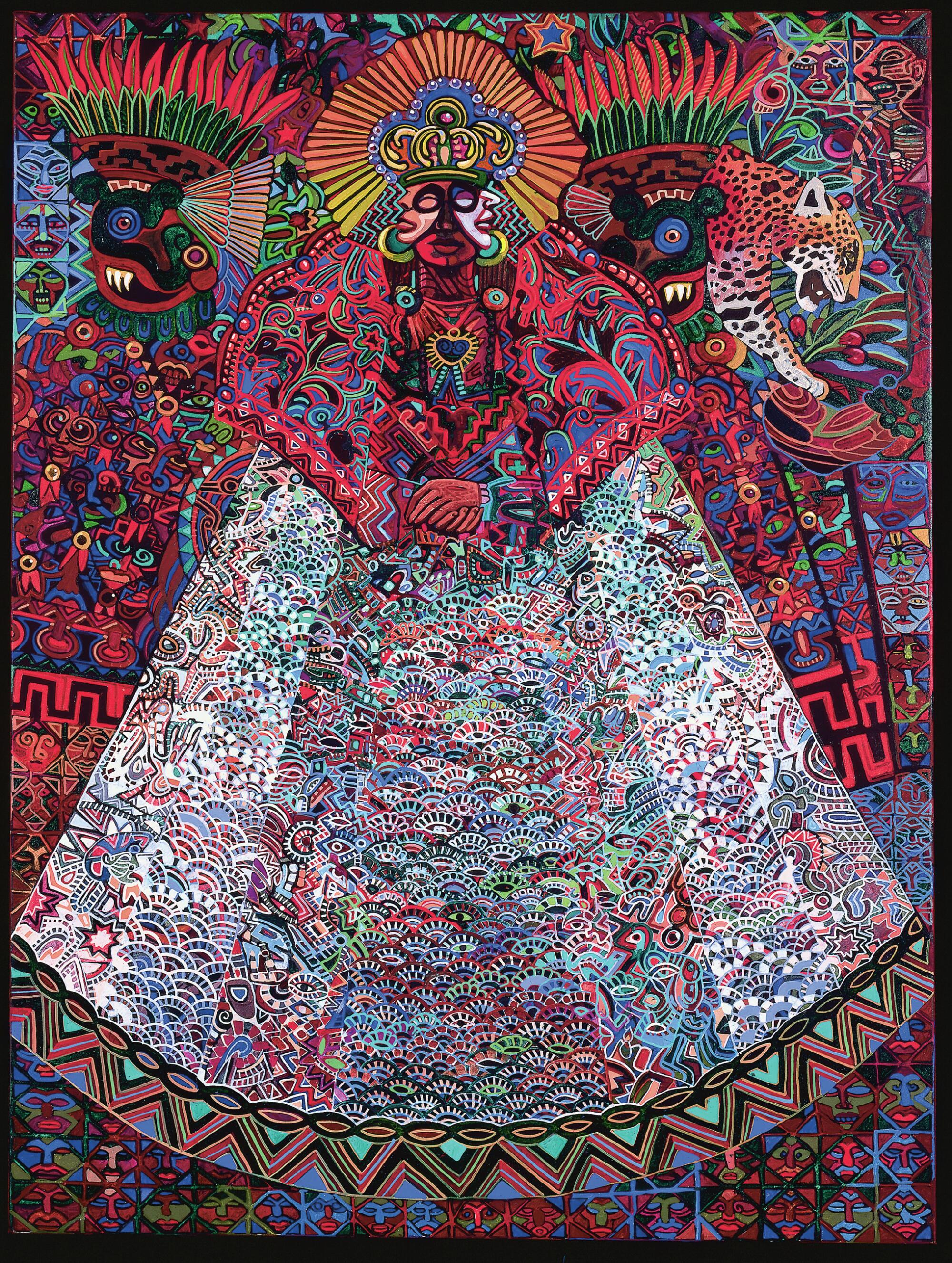

Also on view are paintings from 2006 by L.A. artist Judithe Hernández that were inspired by lotería cards. On the card numbered unlucky 13, Malinche is rendered as a skull with a snake emerging from its mouth. In the Western tradition, the snake could be read as a traitorous symbol, but it is one that connects to Aztec deities such as Coatlicue, a symbol of creation and destruction whose head is composed of two snakes in profile.

It’s an ambiguous piece, but a powerful one. As Hernández states in the catalog: “She found a way to survive using her tongue.”

After it closes in Denver, “Traitor, Survivor Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche” travels to the Albuquerque Museum, followed by the San Antonio Museum of Art. (Sadly, there are no stops planned for Los Angeles.) It is worth the journey for this absolutely essential show.

The story of Malinche is part of the psychology of Mexico, and, by extension, much of the continent. It is a story that — as in the case of Sheriff Villanueva — regularly emerges in the most unexpected places.

Greeting visitors to the exhibition is a painting of a map by L.A. artist Sandy Rodriguez that marks key sites from Malinche’s life along with locations of 19 Indigenous women who went missing or were murdered in 2021. The story of Malinche, says Rodriguez, in a related video is an opportunity to “make contemporary connections to women who have been enslaved, trafficked, who have suffered family separation, that are erased from history and misrepresented.”

The show is a poignant examination of everything that has been said about one of history’s most enigmatic women — while also reflecting on everything Malinche was unable to say for herself.

Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche

Where: Denver Art Museum, 100 W. 14th Ave. Pkwy., Denver

When: Through May 8

Info: denverartmuseum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.