- Share via

In 1981, artist Ulysses Jenkins was teaching at UC San Diego when the media faculty was asked to stage a demonstration for an open house. Jenkins says the initial idea was to set up a VCR and play a video. He had other ideas: “I said, we’re supposed to be the media department, let’s do something more advanced.”

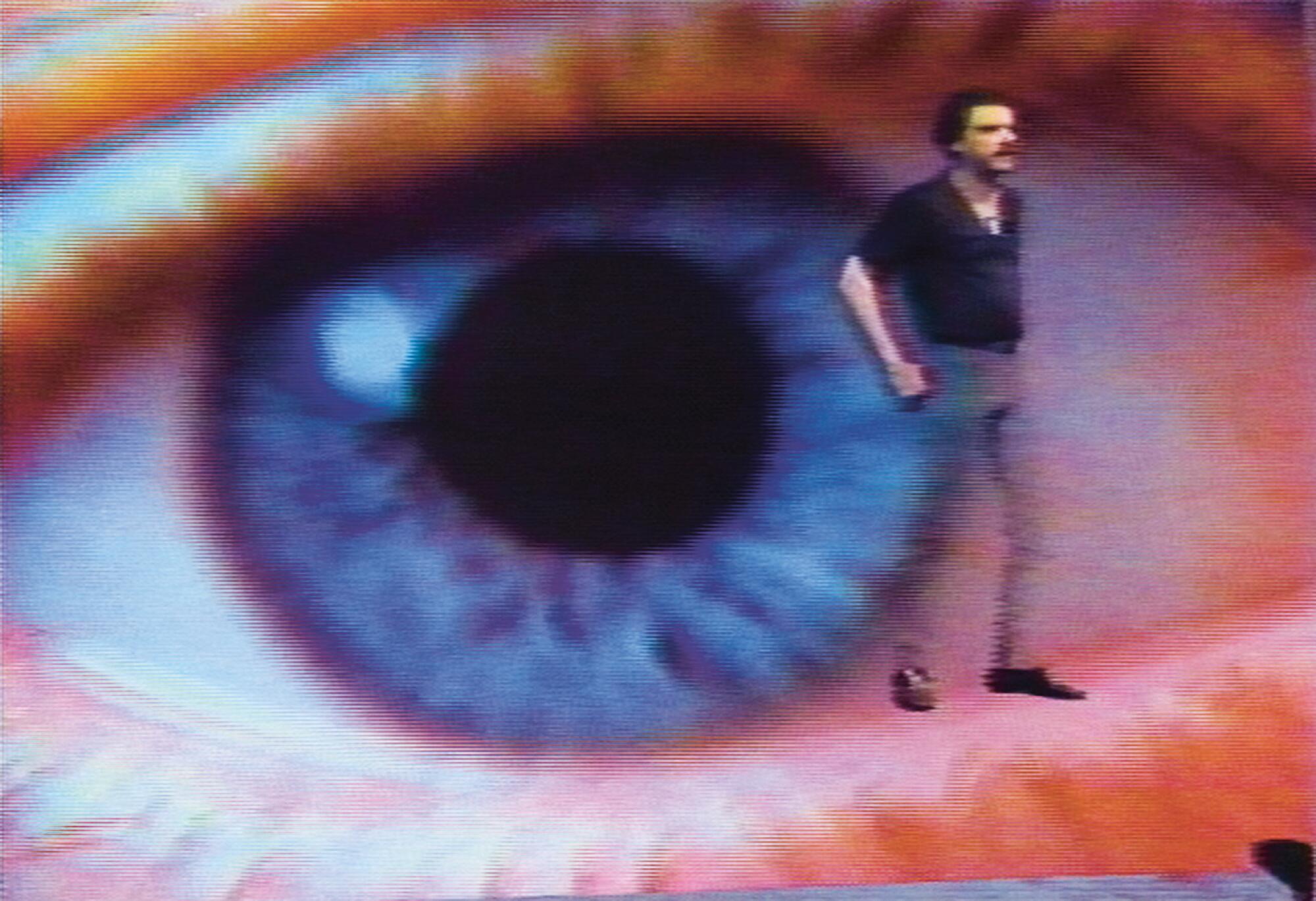

His concept: Establish a live video link between two locations on campus — a student lounge and the media studies complex — and use them to create a two-way broadcast between each site. The feed would include student performances as well as a live lecture by media theorist Gene Youngblood (an early proponent of video art), all against a backdrop of found footage and lo-fi ’80s graphics.

Not being in possession of his own personal satellite, this was no easy task. “Everyone who has Zoom can do this today,” says Jenkins. “But this is 1981.”

To achieve a live link, he had to borrow a microwave unit from a local cable company. Then, to get the feed from the student lounge on one end of campus to the communications complex on the other, Jenkins had to place metallic blankets on top of two buildings so that he could bounce the signals back and forth. More than two decades before companies like Skype helped make two-way video calls part of everyday life, Jenkins had improvised his own teleconferencing system and used it to make art.

The resulting work, titled “Televiews and Cable Radio,” was prescient.

Youngblood’s talk, titled “The Electronics Revolution and the Arts,” examined the ways in which greater public access to broadcast platforms might revolutionize communication — a topic that remains resonant in the age of social media. Moreover, Jenkins’ use of a two-way video feed was predictive of the ways in which we now regularly employ technologies such as FaceTime and Zoom.

Beyond that, what makes “Televiews” enjoyable is that it is absorbingly weird.

Youngblood‘s silhouette materializes over an array of a random images, including Latin American market scenes, a baby absorbing light beams into its open palm and what appears to be a tragic educational video about a pill-popping mom. At times, Youngblood’s words sync uncannily to the images; at others, you’re left scratching your head. Are you looking at scenes from a stage play? Or a Central American uprising? It’s hypnotizing.

Artist April Bey’s sumptuous solo show “Atlantica, The Gilda Region” at CAAM imagines a world in which “all Black people are loved and accepted.”

“Televiews and Cable Radio” is now on view at the Hammer Museum as part of the artist’s ongoing retrospective, “Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation.” The show was organized by Hammer associate curator Erin Christovale and curator Meg Onli, formerly of the ICA Philadelphia, where it went on view late last year. And it illuminates the career of this singular Los Angeles artist.

Jenkins was not only an early adopter of video, he has been a nexus between various ecologies of artists within L.A. and beyond. In collaborative projects that span half a century, he has teamed with conceptualist David Hammons, sculptor and performance artist Maren Hassinger, painter Kerry James Marshall, various members of the art collective Asco, as well as Gary Lloyd, a figure whose preoccupations have included technology and surveillance.

Yet Jenkins’ work, as a body, has been largely unexamined. (Before the Hammer, his only other solo museum show was an abbreviated retrospective at the Crafton Hills College Art Gallery in Yucaipa in 2018.) And it is an extensive body of work — so extensive that trying to see everything at the museum is impossible. (A dozen of his videos are streaming on the Criterion Channel for the duration of the show.) These take the form of straightforward documentaries, as well as hybrid performance-video works that push the boundaries of technology as they deconstruct images and narratives — in particular, those that pertain to race.

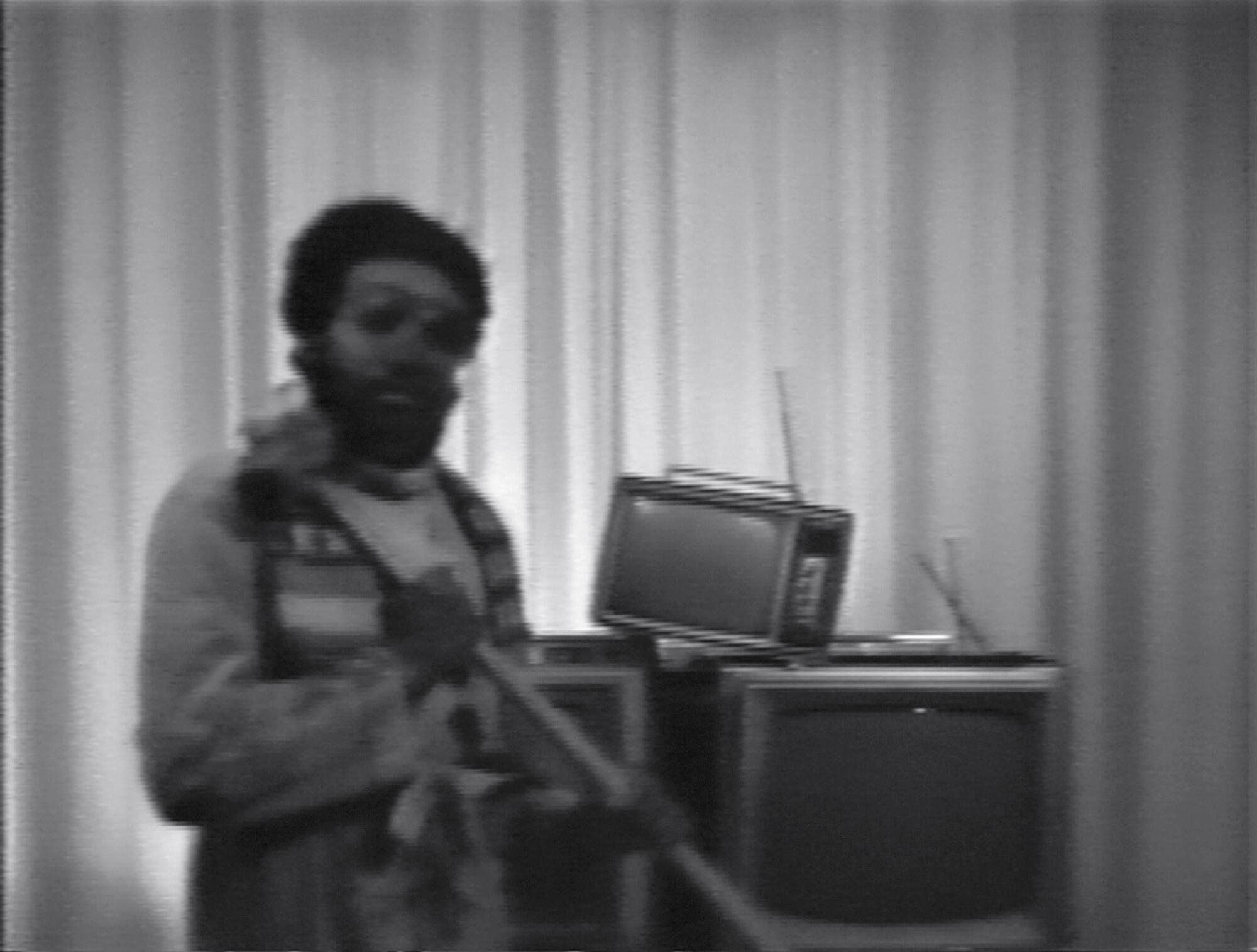

“Mass of Images,” an early short from 1978, shows the artist next to a stack of TVs reciting a bitter refrain: “You’re just a mass of images you’ve gotten to know / from years and years of TV shows / The hurting thing, the hidden pain / was written and bitten into your veins.” This is cut with degrading images of Black people drawn from minstrelsy and early movies such as D.W. Griffith’s wildly racist “The Birth of a Nation.”

“Those early images of Blacks in film, a lot of them were buffoonery,” says Jenkins over a cup of coffee in his Inglewood studio. “For most of the time, it was servitude. If they weren’t a butler, they were a maid. ... And it’s heartbreaking to see the degradation of the characterizations that Griffith came up with. You finally get Black people in Congress and he puts them with their feet on top of their desks eating chicken. That movie is the encyclopedia of stereotypes on Black people.”

“Mass of Images” ends with the artist wielding a sledgehammer as if he might smash the televisions, but he sets it down again, and states: “Oh, I’d love to do this, but they won’t let me.”

It’s an ending that avoids a Hollywood ending; there is no resolution or release — perhaps in acknowledgement that getting rid of the ideologies behind those damaging depictions is going to take more than simply busting up a few TVs.

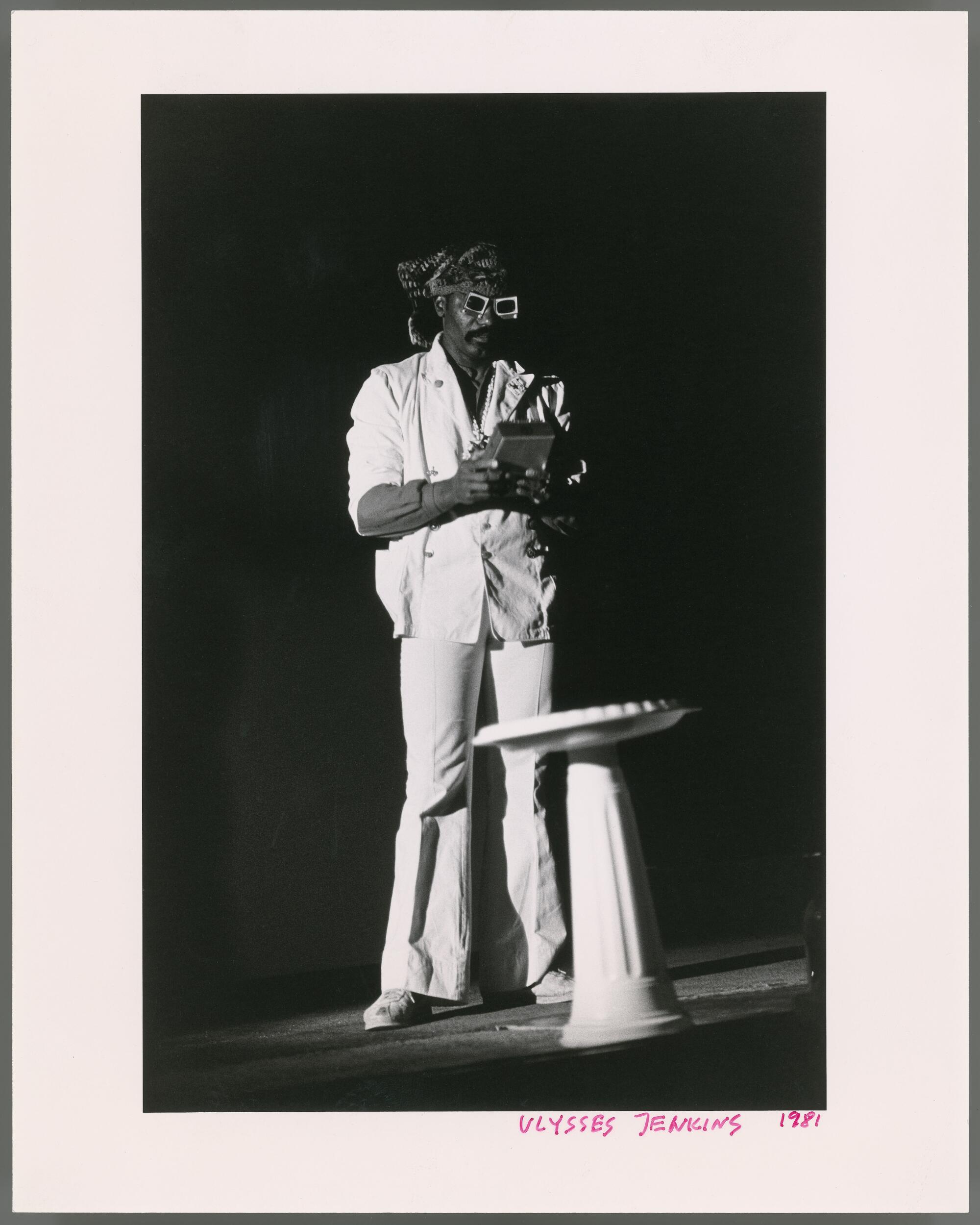

Subsequent works also took on the ways in which the entertainment industry rendered Black people. In “Two-Zone Transfer” from 1979, a man, played by Jenkins, reckons, in hallucinatory ways, with the legacies of minstrelsy. That hybrid performance/video, made when he was a graduate student at the Otis Art Institute (now the Otis College of Art and Design) was done in collaboration with Marshall, who designed the poster, as well as Greg Pitts and Ronnie Nichols.

This was followed in 1981 by “Inconsequential Doggereal,” which shows footage of Jenkins grimacing as he sits naked in a room, spliced with video of newscasts, lawnmowers and a ridiculous advertisement for Valvoline that shows a chimp changing the oil on a car. At moments, it’s as if the figure of Jenkins is being force-fed; at others, he stands up and wags his naked butt at the camera as if to defy the stream. As Onli writes in the exhibition catalog, “It’s the kind of taunting scene one encounters at the end of a Looney Tunes sketch when the Road Runner has outwitted Wile E. Coyote, yet again.”

It is poignant and absurd. And like so much of Jenkins’ work, it looks what it feels like to be Black or a person of color in the U.S., and to see yourself reflected in film and media as if through the distortions of a fun-house mirror.

Jenkins, 75, retains a performer’s magnetism, not to mention a sharp sense of style: On the morning we meet, he is decked out in a matching black shirt and hat bearing an African-style print. The artist inhabits a tidy, sun-dappled studio in Inglewood that contains a lifetime’s worth of ephemera: racks of art catalogs, a framed flyer advertising “Two Zone Transfer” and a sculpture of a black panther seated between two potted palms.

On one wall hangs a series of abstract digital drawings Jenkins recently completed; over the television is a bizarre painting that chronicles an experience with LSD. “On the left side is the people I see,” Jenkins tells me. “Then you have those stalagmites, those are the problems I was having.”

L.A. curator Pilar Tompkins Rivas dives into the underrepresented legacy of Latino photography. Plus, art and Omicron and Sidney Poitier’s theatrical legacy.

Throughout his career, Jenkins has taught: at UCSD, at Otis and, for the last 28 years, in the art department at UC Irvine. If his work has had a low institutional profile, he has nonetheless been influential to generations of students, as well as the myriad artists who have happened upon his videos in group shows — such as the revelatory “Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980,” organized by curator and historian Kellie Jones at the Hammer in 2011. (Jenkins was the only video artist in the show.)

Christovale says, “I like to call him the godfather of so many artists that Meg and I admire, like Martine Syms and Aria Dean and Cauleen Smith,” referring to a generation of creators who often contend with the nature of images in their work. (Dean and Smith, in fact, both have insightful essays about Jenkins in the exhibition catalog.)

The route that led Jenkins to video was a circuitous one.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, he is the son of a barber and a garment worker. He spent his earliest years in South Los Angeles before relocating to the Westside as a youth and came to art at Hamilton High School. For a time, he thought he might focus on commercial work but quickly decided against it. “It was the ’60s and I’d come to the conclusion that I wanted to be a free spirit, and that started my art making,” he says. “The whole notion of being a free spirit, that is a whole idea I pursued in my work.”

For his undergraduate studies, he headed to Southern University in his mother’s home state of Louisiana, a historically Black institution that many of his relatives had attended. He landed there in the fall of 1964, a couple of months after Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. Though Jenkins had visited Louisiana on multiple occasions as a child, returning as a man, he contended with a far more visceral experience of Jim Crow segregation.

On the train trip east, a white man at a train station in Houston demanded he carry his bags. Later, in Baton Rouge, he and a cousin showed up for a tour of the state capitol and were immediately approached by an officer. “The guard comes up on us and says, ‘You boys, what are you doing here?’” he recalls. “I said, ‘I thought this was the tour.’ And he says, ‘You came on the wrong day.’

“So you learn that even if they pass laws in Washington, it doesn’t mean that people are going to abide by them.”

Following graduation, Jenkins lived peripatetically.

There was a stint in L.A. that included a short-lived marriage to a classmate from Southern University, during which he worked as a probation officer in the juvenile system. This was followed by a couple of years in Hawaii, where he worked at a hotel and lived that free spirit existence he had always desired: inhabiting a treehouse, cooking over volcanic lava and harvesting mangos from a nearby grove. The experience of Hawaii — with its blend of Native, Filipino, mainland and other cultures — gave him a vision of multiculturalism that he found compelling, a view rooted more in a shared sense of solidarity than in gauzy notions about a melting pot.

In those early years, inspired by the mural movement in East L.A. and work that appeared on the Westside by the Los Angeles Fine Arts Squad, he pursued mural commissions. In 1976, he painted a piece for the Department of Motor Vehicles titled “Transportation Brought Art to the People” that is still viewable downtown on Hope Street. He was also a collaborator on “The Great Wall of Los Angeles,” the epic series of historical murals in the San Fernando Valley organized by Judy Baca.

The L.A. filmmaker’s installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art plays off a French tradition by injecting symbols of Black culture.

It was fellow painter, Michael Zingale, who led him to video, suggesting they sign up for a workshop. Jenkins had been intrigued by the independent film of the era, such as “Easy Rider” and “Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song.” “And I was very curious about the notions of production,” he says. “This portable medium that you could do without having to raise up all the money you used to have to for movies.”

Soon enough, he had laid his hands on a Sony Portapak, the portable video camera that had been released in the 1960s and had already found a following among artists. Jenkins says it was revolutionary: “There had never been a piece of technology where you could record, erase and play back.”

After that, there was no looking back.

By 1978, he had enrolled in the intermedia department at Otis, where he pursued his master’s in fine art. There, he came into contact with artists such as Chris Burden, Nam June Paik and Bruce and Norman Yonemoto, a sibling duo who were also intrigued by mass media. “The intermedia department,” says Christovale, “was one of the first departments in these art schools thinking about media and video in experimental ways.”

For Jenkins, the experience was formative.

His earliest videos, made before graduate school, take the form of guerrilla documentary. “Remnants of the Watts Festival,” which he began filming in 1972, chronicled the history of the Watts Festival and served as a rejoinder to mainstream media narratives about Watts.

“The media in general was putting out this message to other communities: Don’t go to the Watts Festival, it’s dangerous, they are going to kill you,” he recalls. “I’d been to the Watts Festival. I thought, this is ridiculous.” What he captured is a frank look at the struggles of a community event that had been born of organizing in the wake of the 1965 uprising but later found itself laboring under the strictures of corporate sponsorship.

In the subsequent “District F,” Jenkins tracks a redistricting move that allowed students from South L.A. to attend Santa Monica Community College, an insightful examination of the ways in which boundaries in our educational system are established and maintained. (It should be required viewing among students of pedagogy.)

“Early video art was about the problems with the media that we are still having today: the notions of truth,” says Jenkins. “To that extent, early video art was a construct that was anti-media ... a critical analysis of the media that we were viewing every night.”

Onli says that, in this way, Jenkins was also prescient. “Today we see the dash-cam footage and how that contradicts what is reported,” she says. The artist was creating his own footage, which told a very different story from what played on TV.

And even as his work evolved and grew more artful, more performative, inspired by ritual and ever more surreal — it has continued to document stories that don’t always get told.

Jenkins likens what he does to the storytelling done by West African musician/oral historians known as griots. “The histories and traditions come from the griots,” he says. “They reassert the history and the culture.”

They also connect the past to the future, linking old generations to the new ones. “What I’m trying to say,” he adds, “is that we’re going to have African Americans in the future.”

Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation

Where: Hammer Museum, 10889 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Through May 15

Info: hammer.ucla.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.