Commentary: A major trove of art on paper is coming to light at the Hammer Museum

- Share via

Daylight can be art’s best friend. Organic luminosity emanates the subtle vicissitudes of perceptual life, which enhances looking at art.

Daylight can also be art’s enemy. Fading, bleaching, yellowing — all works of art have a lifespan, even if that lasts for hundreds of years, and too much light can cut it short. Art made with paper is especially vulnerable.

What’s an art museum to do?

At UCLA’s Hammer Museum and its affiliated Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, which both collect works on paper, the answer is to embrace an established museum practice while giving it an updated twist. As part of the Hammer’s ongoing, $100-million renovation and expansion project at its Westwood building, a new Grunwald study-storage facility for works on paper is nearing completion, expected in early spring.

In addition, a 3,100-square-foot exhibition gallery dedicated to the paper medium will also be publicly unveiled on Sunday — a Hammer first. It launches with part one of a two-part survey of acquisitions from the last decade.

The gallery and the Grunwald are now front and center on the museum’s third floor, adjacent to the Hammer’s main galleries, rather than being tucked away. Call it a coming-out party for works on paper, as an exceptional collection sees a new light of day.

For hundreds of years, European and American museums have had such study-storage facilities, including at UCLA, where fragile art on paper is securely stored when not on temporary view in exhibition galleries. Rarely are they featured. Different museums have different policies for gaining access to study-storage, often requiring professional credentials.

When the Grunwald facility is finished, however, the plan is to make appointment-based requests available to the general public. The arrangement will be relatively unique in L.A.

Want to see a riveting 16th century engraving of a personification of divine retribution by Albrecht Dürer, the incomparable German Renaissance genius? How about a harrowing 2010 image by Kara Walker of a sailing ship tossed at sea, a pair of elegant Black hands rising from beneath the waves to conjure the slave ships of the bitter Middle Passage? Care to compare early and late examples by the socially conscious ’60s L.A. Pop artist Corita Kent? One-on-one viewing of prints, drawings or photographs will be possible.

The Grunwald has been collecting works on paper since its 1956 founding through a gift to UCLA of around 1,500 woodcuts, engravings, etchings, lithographs and other prints. The donor was German Jewish émigré Friedrich Grunewald, a clothing manufacturer, who changed his name to Fred Grunwald when he fled brutal Nazi persecution in Wuppertal in 1939 with his wife, Gertrud Löwenstein, and young children, Ernest and Lotte. The Gestapo had seized the collector’s first cache of graphic art, its specific details only partially known today. He began to rebuild after relocating to Los Angeles.

According to Cynthia Burlingham, the center’s director, the Grunwald collection is now strongest in European and American prints and drawings, with significant holdings in Asian (especially Japanese) and Latin American (especially Mexican) graphic art. Works date from the Renaissance to the present.

In 2005, the Hammer Museum began to collect international contemporary art, with emphasis on artists working in Southern California. Drawings are a collection core. (Prior to her 1999 arrival to lead the Hammer, Ann Philbin was director at the Drawing Center in New York.) The number of paper holdings is relatively modest —1,660 sheets — but together with the sizable Grunwald collections, the museum is home to nearly 52,000 works on paper.

About 10% are drawings or photographs, while the rest are prints. Together they constitute one of the nation’s most important graphic arts collections.

In total, roughly 95% of the Hammer Museum’s art collection consists of works on paper. Noisy complaints that art museums show only a small fraction of their permanent collections often forget such stats. For reasons of conservation — a primary museum responsibility — that’s art that in fact should spend most of its time in storage.

The pressing question is how to reconcile a museum’s basic preservation function with an equally important obligation for public accessibility. The new Grunwald Center and the adjacent gallery seek to offer an answer. Architect Michael Maltzan has designed a space that is big on transparency, metaphorical and otherwise. For the first time, works on paper will assume a central position within the museum — visually, physically and conceptually.

During the larger Hammer renovation and expansion project currently underway, the building’s facade and Wilshire Boulevard entryway are getting reconfigured. An interior elevator bank will become a primary access path to the museum’s third-floor galleries, currently reached by stairs. One side of the arrival lobby is a glass wall opening directly onto the Grunwald.

Inside the study space, a window wall onto Wilshire fills the long room with natural light; double shades, one set for filtering sun and the second for full blackout, control illumination. Shelving on the opposite wall, plus tables running the length of the study room, provide areas for easy art display. A glass door at one end opens onto the gallery, while the other end opens into the museum’s boardroom.

An even larger room behind the display wall will house high-density compact storage units, which can accommodate virtually the entire Hammer and Grunwald graphics collections and have room for considerable growth.

A chunk of this welcome institutional transformation’s cost has been covered by a $2-million bequest from the estate of art dealer Margo Leavin, who died in October at 85. (Seven years ago, a $20-million UCLA gift from Leavin — the largest ever to any UC campus from an alumna — underwrote most of the construction of a building for the school’s celebrated graduate studio art program.) Since 1975, Leavin donated 83 works on paper to the Grunwald (some gifts in concert with her longtime business partner, Wendy Brandow), beginning with two lithographs by second-generation American Abstract Expressionist Matsumi Kanemitsu.

The current financial bequest also comes with art. Among the 41 previously unannounced Leavin gifts are three works on paper by Jasper Johns and four by Claes Oldenburg, making a total of six by each of those artists given over the years. (A 1961 Oldenburg painted sculpture of an ice cream cone also is headed to the Hammer.) John Baldessari, Chris Burden, Roy Dowell, Jill Giegerich, Stephen Prina and Alexis Smith are among the Los Angeles artists whose work is part of the bequest.

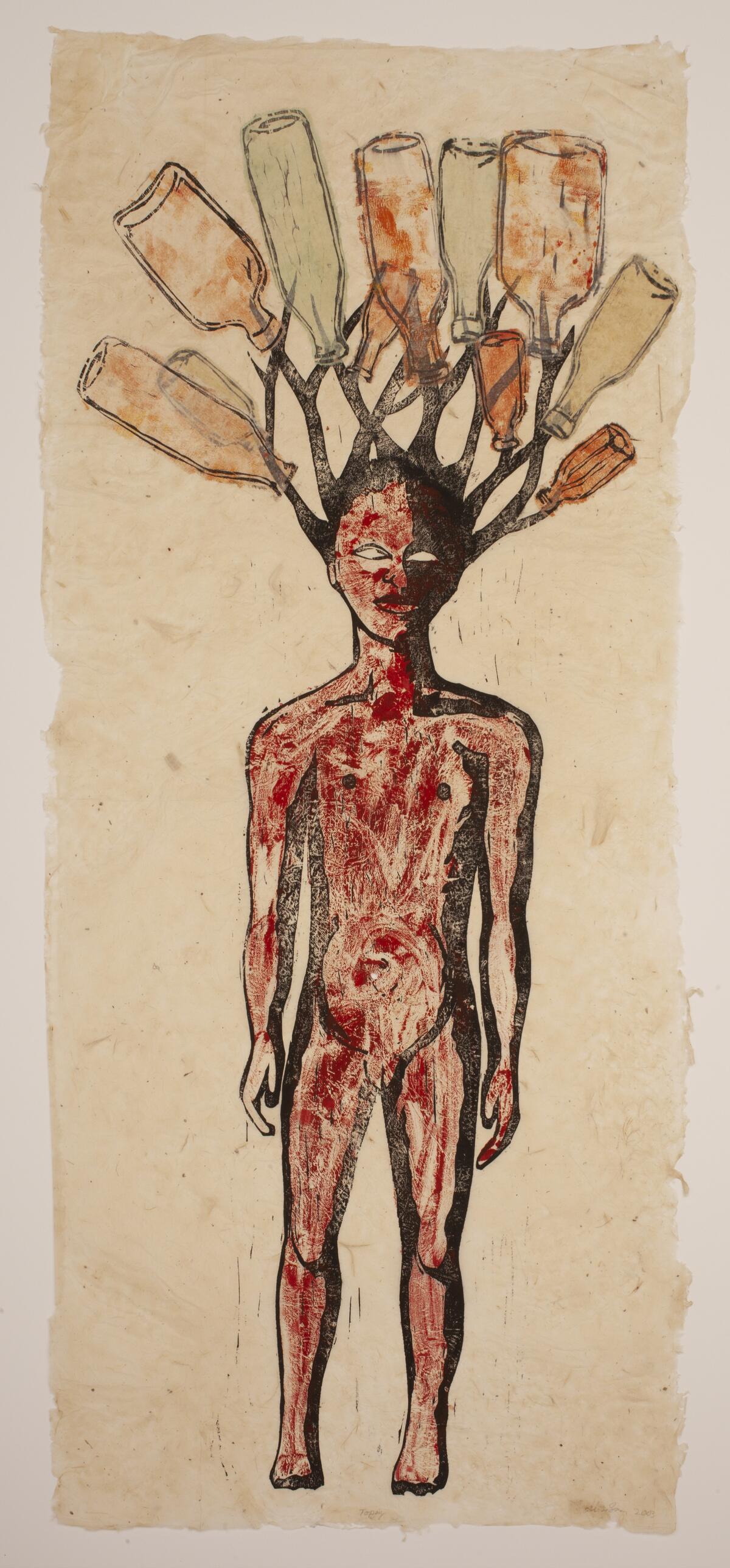

The gallery’s debut exhibition, “A Decade of Acquisitions of Works on Paper,” is organized by Burlingham and Connie Butler, Hammer chief curator. Among the 51 purchases and gifts are seven donated by Joel Wachs, director of the Andy Warhol Foundation and a former L.A. city councilman, whose drawing collection is destined for the museum. A second acquisition-installment will follow for the summer, with a show of Picasso cut-paper graphics on tap for the fall and geometric abstractions by nonagenarian British painter Bridget Riley, jointly organized with the Art Institute of Chicago and New York’s Morgan Library, in the winter.

Speaking of Picasso, the auction last November of “Profil,” a UCLA-owned 1930 painting hammered down at $7.34 million, will create a museum acquisition endowment mainly for works on paper. According to Philbin and Burlingham, annual endowment income will be split between the Hammer and the Grunwald, with principal available should an exceptional opportunity arise.

The new positioning of works on paper within the museum is more than coincidental. It represents a profound cultural shift that has unfolded over the last 50 years.

With the rise of idea-oriented Conceptual art, drawing — the most direct technique for registering the development of artistic thought, brain to hand to paper — was invigorated. Technological innovation made camera work, previously a cultural stepchild for more than a century, ubiquitous. Prints, a less expensive alternative to paintings and sculptures, grew in popularity as a medium after the emergence of the first flourishing U.S. market for contemporary art.

One irony is inescapable: When UCLA assumed pricey operation of the late oilman Armand Hammer’s failed Westwood museum in 1994, the deal was paid for through the disappointing sale of its Codex Leicester — a sheaf of 36 drawings and text by Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci. (Bill Gates bought the Codex, the only one by Leonardo in an American museum, for just under $31 million.) Now, the Hammer’s Grunwald project embodies fundamental changes in cultural values around works of art on paper that are firmly in place.

Let the sunshine in.

'A Decade of Acquisitions of Works on Paper'

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood.

Contact: (310) 443-7000, www.hammer.ucla.edu.

Through May 1. Closed Monday.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.