How ‘A Raisin in the Sun’ made Sidney Poitier’s Broadway legacy unforgettable

- Share via

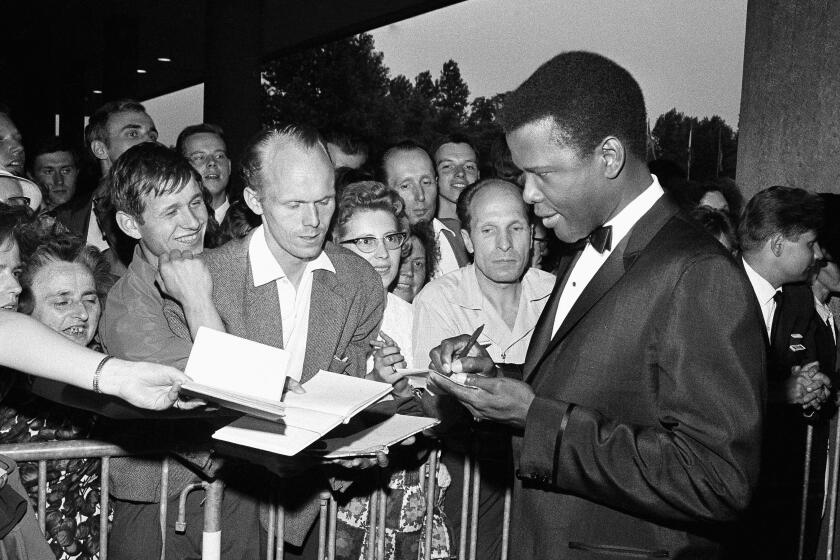

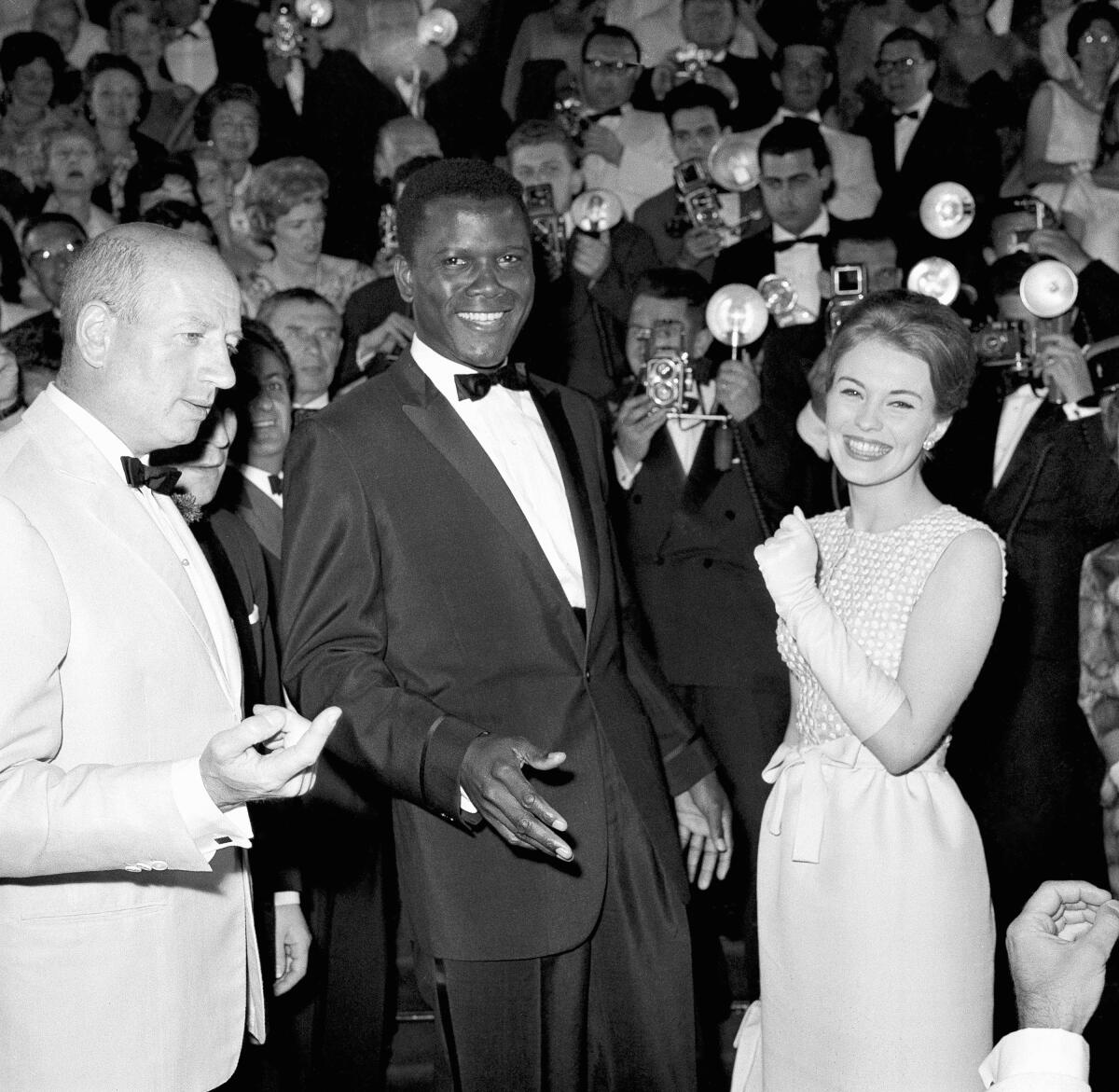

It is impossible to overestimate Sidney Poitier’s Hollywood legacy. The elegance of his path-breaking example on screen opened the hearts, minds and wallets of the moviegoing public and tugged at the reluctant, mercantile conscience of the film industry.

Poitier, whose death at 94 was announced Friday, will always be remembered for being the first Black actor to win the Academy Award for lead actor. But his imprint on theater history, while closely associated with one play, should not go unrecognized.

Poitier’s stage start wasn’t auspicious. His inexperience and “very thick West Indian accent,” as Poitier put it, got him thrown out of his audition for the American Negro Theatre in Harlem. But he wound up graduating from the community theater group’s acting school, where Ruby Dee and Harry Belafonte, colleagues whose careers would intersect with his own, also received training.

Poitier’s Broadway break came in 1946 with an all-Black production of Aristophanes’ “Lysistrata,” which closed shortly after it opened. The following year he landed a role in “Anna Lucasta,” a play by Philip Yordan (based on Eugene O’Neill’s “Anna Christie”) that fared a little better, lasting almost a month. The show was American Negro Theatre’s first Broadway success, but opportunities in the theater were few and far between.

The actor who helped break down Hollywood’s onscreen color barriers before becoming one of the top box-office draws of the 1960s has died at 94.

The road to movie stardom wasn’t easy, but talent (sustained by scrappiness) won out. When he returned to Broadway in 1959 for the premiere of Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun,” he was already famous. The cast, which included fellow American Negro Theatre alum Dee, was directed by Lloyd Richards. This trailblazing play, about a Black Chicago family struggling for a piece of the American dream, has become a canonical work of 20th century drama.

Brooks Atkinson notes in “Broadway,” a chronicle of his years as drama critic, that “Sidney Poitier, who had become a Hollywood star, played the leading part in his effortless style with personal magnetism and professional deftness.” Hansberry, Poitier and Richards were nominated for Tony Awards, but William Gibson’s “The Miracle Worker” dominated that year.

Atkinson’s comments on Hansberry’s play in “The Lively Years,” another of his histories, are perfunctory: “‘A Raisin in the Sun’ is not a revolutionary play on a revolutionary subject but a passionate statement of home truths about representative people.” So much for the historical insight of critic who has a Broadway theater named after him.

To understand the significance of “A Raisin in the Sun” we must turn to James Baldwin, who, in a 1968 essay on Poitier published in Look magazine, writes expansively about the experience of being in the audience for this watershed production.

I will always remember seeing Sidney in “A Raisin in the Sun.” It says a great deal about Sidney, and it also says, negatively, a great deal about the regime under which American artists work, that that play would almost certainly never have been done if Sidney had not agreed to appear in it. Sidney has a fantastic presence on the stage, a dangerous electricity that is rare indeed and lights up everything for miles around. It was a tremendous thing to watch and to be made a part of. And one of the things that made it so tremendous was the audience. Not since I was a kid in Harlem, in the days of the Lafayette Theatre, had I seen so many black people in the theater. And they were there because the life on that stage said something to them concerning their own lives. The communion between the actors and the audience was a real thing; they nourished and recreated each other. This hardly ever happens in the American theater. And this is a much more sinister fact than we would like to think. For one thing, the reaction of that audience to Sidney and to that play says a great deal about the continuing and accumulating despair of the black people in this country, who find nowhere any faint reflection of the lives they actually lead. And it is for this reason that every Negro celebrity is regarded with some distrust by black people, who have every reason in the world to feel themselves abandoned.

I have my own personal history with a “A Raisin in the Sun.” Like many people, I first encountered the play through the 1961 film, in which Poitier reprised his performance as Walter Lee Younger, the son who would rather invest the insurance money from his father’s death in a liquor store than go along with his mother‘s plan of buying a home on the white side of town.

I remember watching the movie with my father in our first home, so I was still in elementary school. The moment is vivid in my memory because at the end of the film I saw my gruff old man wipe tears from his eyes. I had never seen him cry before, so I asked what was going on. Choked up, he explained that he felt bad for a family that was just trying to have a better life. I don’t remember ever having an exchange like this with my dad again.

In his article on Poitier, Baldwin expresses the wish that Poitier and Marlon Brando would reignite Broadway with the luminosity of their acting. But he understood why they were gone: “Broadway is almost as expensive as Hollywood, is even more hazardous, is at least as incompetent, and the scripts, God knows, aren’t any better. Yet I can’t but feel that this is a great loss, both for the actor and the audience.”

Poitier returned to Broadway in 1968 as a director for the short-lived production of Robert Alan Aurthur‘s “Carry Me Back to Morningside Heights,” but his Broadway credits end there. I regret never having the opportunity to see him onstage, but my gratitude for what he accomplished in the theater through “A Raisin in the Sun” is immense.

Broadway ought to say thank you by dimming its lights in honor of an actor who, beyond the miracle of making my father cry, opened the door to dramas about Black humanity. He was a beacon, and his presence on stage and screen lifted us all.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.