Appreciation: Joan Didion’s indelible study of grief gave me the tools to save myself

- Share via

Sixteen Christmases ago, my parents gifted me a copy of “The Year of Magical Thinking” by Joan Didion. It was a new book, published that fall, with an eggshell cover and a slim turquoise spine. I knew Didion’s work. It was all but a requirement of my existence: I was a female college journalist, editor of the school paper and an English major to boot. Still, I didn’t read the book right away. Perhaps a memoir about the death of a spouse and the looming loss of a child seemed too distant to comprehend. At the time, I had never lost anyone close to me. I put the book on a shelf and forgot about it.

A few months later, in the summer of 2006, I fell in love. Had it ended differently, it would have been a cliché: I traveled to Southeast Asia, met a man and discarded my plans for teaching English to follow him wherever he was going, which happened to be on a backpacking trip with his cousin. He was beautiful and funny but prone to melancholy and haunted by shadows.

Shortly after we met, he described how, a year and a half earlier, on Dec. 26, 2004, he had been scuba diving when the water suddenly pulled him down, down, down. When he was able to surface, there were bodies floating in the sea. He didn’t know it yet but he had survived a tsunami that killed hundreds of thousands. For a few days, his family thought he might be one of them. When he told me this story, he wept.

We traveled to Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Then, one morning in August, I woke up but he did not. I tried to make him: I shoved and shook, slapped and shrieked. I pressed on his chest and breathed into his mouth, but my air came back to me, useless. The staff at a nearby health clinic, where he was delivered in the bed of a rusting pickup truck, tried all the same things I had. We were in a poor village in an isolated valley in Laos; there were no paddles with which to shock his chest or adrenaline to shoot into it.

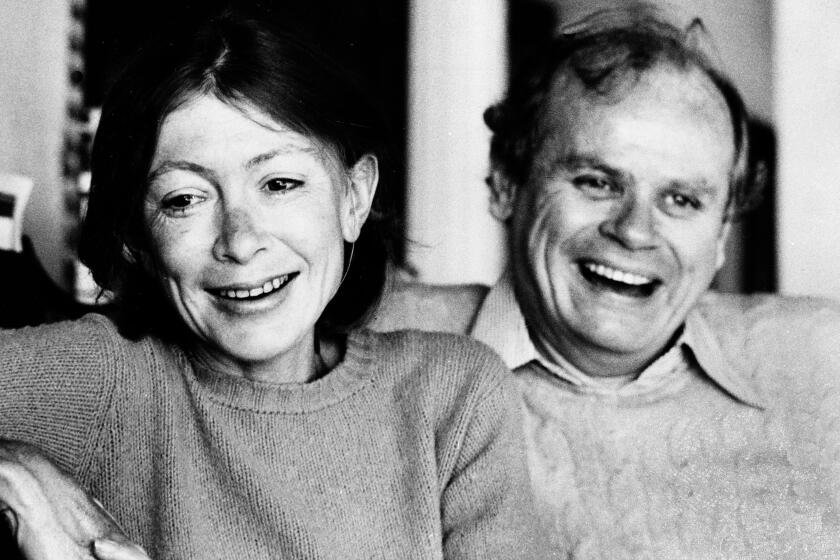

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

After a few minutes, the nurses shook their heads. His cousin shook her head too. It was over.

The clinic staff had put his body in a room with a dirt floor. It was dark and cool for the tropics. Someone made it clear that I was to retrieve any personal items left in his pockets. I walked over to the slab where he was lying. When I touched him, I began to scream.

There was a cremation in his chosen home (Thailand) and a memorial service in his birthplace (Canada). I declined to attend the ritual burning but flew to be at the gathering of friends and family in Vancouver. I was a stranger to them, a 20-year-old American who somehow wound up at their loved one’s side when he died, the last person to hear him speak, laugh, breathe. What right did I have to that experience, that privilege? None, I thought, ashamed.

I flew back east to start my senior year of college. In the environs of my past life, he was the stranger. Friends and teachers told me how sorry they were and that they were sure he had been an interesting person. “I can’t imagine how I would feel if my boyfriend died,” an acquaintance told me, crying at the mere thought. I comforted her through gritted teeth. Condolence cards showed up at my apartment. The notes scrawled inside reminded me that things would get better.

I slept on the couch because my bed — any bed — seemed like a grave.

***

I don’t recall when, exactly, I slid “The Year of Magical Thinking” off my bookshelf, or why. I do remember that it seemed like a better choice in the moment than “Where Is God When It Hurts?” which sat uncracked on my kitchen counter where someone had left it for me.

I read Didion’s memoir in gulps and as fast as I could, baffled and ecstatic to see my own thoughts rendered on the page: the need to detail to myself, again and again, what happened; the desperate search for omens; the toggling between lucidity and fantasy. “I didn’t believe in the resurrection of the body but I still believed that given the right circumstances he would come back,” Didion writes of losing her husband, John Gregory Dunne. “He who left faint traces before he died.” Of course my boyfriend could come back, I thought. I had the book he was reading when he died and his favorite black shirt; I could smell him because I had taken to wearing his Le Male cologne.

Early in the book, Didion laments that literature about grief “seemed remarkably spare.” The poetry, though, was robust, and it “seemed the most exact.” Didion quotes Gerard Manley Hopkins and e.e. cummings. She talks of days when she “relied” on Matthew Arnold and W.H. Auden. “I seemed to have crossed one of those legendary rivers that divide the living from the dead,” Didion writes, “entered a place in which I could be seen only by those who were themselves recently bereaved.” For me, the only person who fit that description was Didion. But I wondered if I could find something similar in poetry — if more of the empathy I craved was out there, waiting, as Didion’s memoir had been.

Once I began looking, I couldn’t stop. I carried volumes of verse home from the university library, until stacks of them littered the floor of my apartment. I searched online for “poems about death.” I returned to the works of Shakespeare and the New York School assigned in English courses past.

How to describe the thrill of finding Edna St. Vincent Millay articulating why something as simple as driving my car, an old Honda I’d had since high school, could rattle my equilibrium?

And entering with relief some quiet place

Where never fell his foot or shone his face

I say, “There is no memory of him here!”

And so stand stricken, so remembering him.

Here was Mary Oliver, dismissing the cultural imperative — the American one, anyway — to buck up, move on:

From the complications of loving you

I think there is no end or return.

No answer, no coming out of it.

Which is the only way to love, isn’t it?

This isn’t a playground, this is

earth, our heaven, for a while.

Therefore I have given precedence

to all my sudden, sullen, dark moods

that hold you in the center of my world.

I kept going. I read Elizabeth Bishop, John Keats and Emily Dickinson. My advisor suggested I try Edwin Muir. This was after I told him I was changing the topic of my senior thesis. My original subject was pretentious — something about constructions of masculinity in Southern literature that I thought made me sound smart. Now I wanted to write about the experience I was having, of locating nourishment in the language of strangers. I described it as finding an empathic community. I wanted to analyze poems, line by line, to understand why certain words and rhythms made me feel the way I did.

I wrote a letter to my boyfriend, telling him of my plans. I tucked it in a box filled with the other missives I had written him since he died. Eventually, there would be dozens.

***

Didion was invited to speak on campus the following spring, in 2007. It felt like kismet. My thesis was done, or nearly so, and the introduction relied heavily on Didion’s memoir. “The Year of Magical Thinking” was a sensation by then: a bestseller, winner of the National Book Award and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She read from it at the event, then took questions.

Afterward, I got in line to have her sign my copy of the book. I didn’t plan to say anything, other than “thank you.” But when I got to the front of the line, I blurted it out. All of it.

“What happened to you kind of happened to me,” I said, immediately regretting that I was comparing the tragic end of a fleeting, youthful romance to her losing the two most important people in her life. Still, I kept going: “My boyfriend,” I explained, “died right in front of me.”

She watched me as I spoke, her wizened face betraying no reaction. When I finished, she said in a steady but kind voice, “You are far too young for that.”

The sentence was trademark Didion: bald and blunt, yet generous. In the months since grief had become my life’s unwelcome passenger, no one had said anything so true. Disarmed, I searched for what to say. “Thank you” could wait. Maybe it was implied all along.

“He was far too young for that,” I said.

She nodded, and signed the book.

***

I thought about this encounter several nights ago, when I received word that a friend had died of an aggressive brain tumor. He leaves behind a wife and daughter. They are far too young for that, I thought as I read the email bearing the news.

A few hours later, Joan Didion died. She was 87. She leaves behind a colossal literary legacy, including her indelible study of grief. It is at once singular and familiar — a testament, an offering and a compass. It steered me through darkness and led me to the words of fellow travelers. It gave me the tools to save myself.

I understand now that we are all too young for that: Until we know grief and the causes of grief, we are not ready, because we cannot be. Even at nearly 70, when Didion lost her husband and daughter, she was too young. There was no preparing for it — there was only experiencing it, muddling through it, being changed by it.

“We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away,” Didion writes, “failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.”

I still have the book he was reading, his favorite shirt and his cologne. They’re in the box with the letters I wrote to him, the products of my own year of magical thinking. Except it wasn’t just a year. Grief never ends. It is an ocean: rising and falling, and sometimes surging with a violence that threatens to swallow you whole.

Just last year, after a bout of being pulled down, down, down into the depths, I had a Mary Oliver line tattooed in tiny script on my forearm: “And I say to my heart: rave on.” It is a reminder that the waves won’t stop coming. All I can do — all any of us can do — is fight to breach the surface and to ride the swell, again and again, forever.

Seyward Darby is the editor in chief of the Atavist Magazine and the author of “Sisters in Hate: American Women and White Extremism.” She lives in New York.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.