Commentary: Does ‘West Side Story’ work best as a film? An opera? Neither?

- Share via

In what felt like a startling New York moment, ballet, avant-garde music theater and Broadway were putting it together in 1984. Something was coming, something good. Distinct genres of music theater were reinventing themselves in complementary ways thanks to Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, Jerome Robbins, Philip Glass and Robert Wilson. An optimistic, innovative new era for the art form seemed just around the corner.

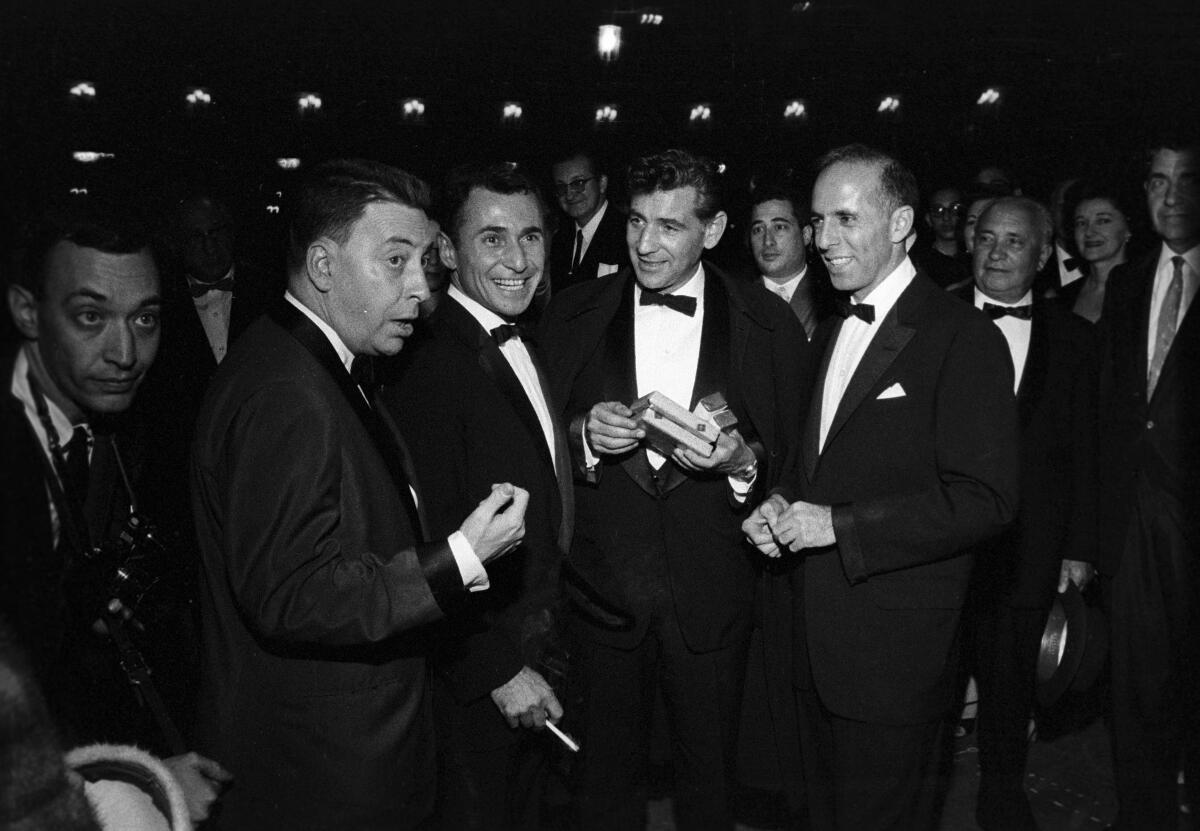

At a Midtown recording studio, Bernstein conducted, for the first and only time in his career, “West Side Story” with, in another first, opera stars. Meanwhile, Sondheim’s latest hit, “Sunday in the Park With George” — his most imaginative, game-changing show yet, one which dealt with the very act of adventurous, obsessed art-making — was playing practically around the corner, at the Booth Theatre on Broadway. Across the river at Brooklyn Academy of Music, “Einstein on the Beach,” the 1976 Philip Glass/Robert Wilson opera, was given its first revival; it’s now recognized as a singular reinvention of American opera. At the tony Lincoln Center, New York City Opera presented Glass’ latest opera, “Akhnaten,” and New York City Ballet premiered “Glass Pieces,” two more landmarks.

For the record:

12:08 p.m. Dec. 20, 2021In a photo in an earlier version of this article, playwright Arthur Laurents was misidentified as composer Stephen Sondheim.

4:12 p.m. Dec. 13, 2021An earlier version of this article said “Sunday in the Park With George” played at the Winter Garden Theatre. It was at the Booth Theatre.

Critics’ reactions, comparisons to the 1961 movie and more to know about the new “West Side Story” starring Ansel Elgort and Rachel Zegler.

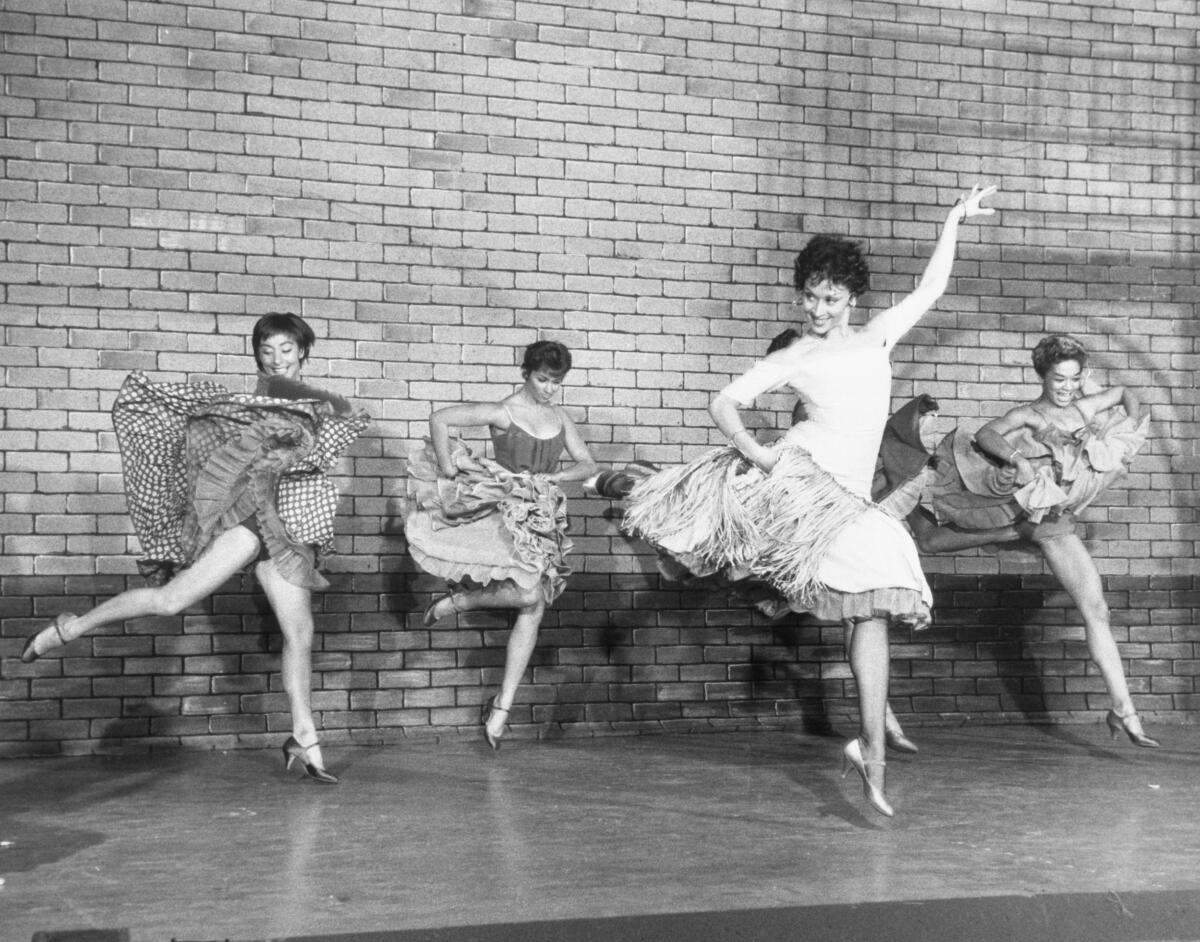

“West Side Story,” itself having beckoned a Broadway revolution when it premiered in 1957, was at the center of it all. A 27-year-old Sondheim came to immediate prominence as lyricist for Bernstein’s songs. Robbins was one of the show’s creators, its choreographer and director. He was involved in the creation of “Akhnaten” and created “Glass Pieces,” which includes music from the opera.

All but one of these mid-1980s projects were widely acclaimed. The seemingly surest bet, though, led to head-scratching. Bernstein’s “West Side Story” recording featured José Carreras, a tenor from Barcelona with a heavy Spanish accent, as Tony, and the New Zealand soprano Kiri Te Kanawa assuming a noticeably fake Spanish accent for Maria — choices that were at odds with the Anglo and Puerto Rican identities of this updated Romeo and Juliet. The Greek and German mezzo-soprano Tatiana Troyanos sang the part of another Puerto Rican character, Anita. What could be crazier, or more tone-deaf, than that in a drama involving racial conflict?

What could be crazier and more retrogressive was the lavish 1961 movie adaptation of “West Side Story,” which has now been lavishly remade by Steven Spielberg and opens in theaters today. The 1961 film won the hearts of millions along with 10 Oscars, including for best picture. But it softened a raw, revolutionary musical’s essential sharp edges and sugared Bernstein’s music through Hollywood-style orchestrations and flaccid conducting. That is how the music became widely known.

Bernstein was not involved in the film’s making and was hardly happy with it. His own recording was his corrective, released 23 long years later, by which time “West Side Story” had gotten somewhat stale as a stage show. The once-groundbreaking 1957 Broadway musical had become dated, and criticisms of its racial stereotyping mounted, particularly because of how Puerto Ricans were represented in it. The music had, of course, lived on. “Maria,” “Tonight” and “Somewhere” entered the Great American Songbook. “Symphonic Dances From West Side Story,” which Bernstein brilliantly arranged from the show’s dance numbers, was on its way to becoming an international orchestra staple.

With the American music theater revolution of 1984, however, “West Side Story” might just be a natural opera. It wasn’t even a new idea. The two most groundbreaking American operas before “Einstein on the Beach” had been the Gershwins’ “Porgy and Bess” and the Virgil Thomson/Gertrude Stein-created “Four Saints in Three Acts,” both of which premiered on Broadway in the mid-1930s with all-Black casts.

Bernstein’s operatic recording takes his music into a remarkable new realm of depth and expression that seemed impossible on the Broadway stage, where performers needed to be young actors who could credibly sing and dance. But get past some of the problematic accents on Bernstein’s recording (Though Troyanos, a great singing actress who happened to grow up on the Upper West Side, proved an incomparable Anita), and a previously unknown musical magnificence arises. Songs become arias, the inner expression of what cannot be said. The orchestra weaves a drama of Verdian power.

Everything about how “West Side Story” has unfolded suggests opera might be an ideal form to move the needle. Opera productions need not be remakes or revivals (the Broadway “West Side Story” revivals have not moved the art form forward) but can serve as the opportunity to treat classic works as revelatory living art, ever ready for contemporary reimagining and relevance. The suspension of disbelief is opera’s highest aim. The opera house offers the finest musical and theatrical resources. These days the actors most skilled at singing and acting (and sometimes even dancing) are found in opera, as is the most imaginative theater.

Bernstein nonetheless insisted that “West Side Story” is not an opera because it doesn’t resolve itself in music. That qualification went out the window in 1984. Anything you wanted to call an opera could be an opera. Yet for the most part “West Side Story” on the lyric stage has pretended not to be an opera after all. Typically, it becomes an uncomfortable hybrid of Broadway and opera, which is to say a luxury version of the Broadway show. When it tries more, it can really go astray, as happened at a ludicrous Salzburg Festival production in 2016 staring Cecilia Bartoli.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

In an attempt to right the 1961 film’s many wrongs, Spielberg made everything about “West Side Story” seemingly more real. He’s put together an exceptional artistic team, most notably hiring Gustavo Dudamel to conduct the score, which he does with genuinely Bernsteinian flair. Justin Peck’s choreography smartly and graciously updates Robbins. Tony Kushner adds sophisticated, moving back story. The late Sondheim himself served as advisor.

The new film is clearly a labor of love. The cast was chosen with care, believable young actors who are capable singers and dancers and whose devotion is evident in every frame.

Spielberg appears to be after truth. The film looks like the cheerless 1950s Upper West Side. The gangs may dance, but their violence is the screen violence moviegoers have come to expect. We are asked to consider ethnicities, where the youths came from and their reasons for hate. Dudamel’s incredibly dynamic conducting animates everything the music touches. His sense of nuance supplies whatever depth the characters are not quite experienced enough to show on the screen.

Kushner invented a new character to replace Doc, who owned the hangout drugstore with his Puerto Rican widow. This is the role for Rita Moreno. She won an Academy Award for her Anita in the earlier film, and in this one she sings “Somewhere,” Bernstein’s greatest song. The key number in the show, and meant for an imaginary ballet, is about an unreachable better world just around a corner but that we are historically incapable of finding. Here, though, Moreno, having just broken up an attempted rape of Anita, is an 89-year-old wearied of the world. In this wistful “Somewhere,” she is accompanied by Dudamel, as though he were holding her in his loving arms. It is deeply touching.

It is also virtuoso, emotion-laden filmmaking that, however sincere, lays it on thick. This “West Side Story” redux relies on one in a series of modern cinema verité devices to tell — or hit you over the head with— a West Side story that overwhelms the music.

That is not to say that Sondheim doesn’t give Bernstein’s score a fighting chance. At the screening I attended, it could be so loud I had my fingers in my ears (not a good way to listen to a musical). Highs sizzled unnaturally. Bass boomed unnaturally. Singing sounded flat, unnatural. The especially showy Dolby Atmos audio system made the whistling that opens the film sound cool but unnatural. “Cool” wasn’t cool but jacked-up hot. The sound design ever distracted. Instruments didn’t blend, they blared.

From his earliest days, and with “Jaws” in particular, Spielberg has demonstrated a knack for using music. But that knack fails him in “West Side Story,” where he all too often underscores the score by cutting to the beat, trusting his own instincts above Bernstein. The dance and musical numbers dazzle (it is Spielberg, after all) but no more than that, and that is not “West Side Story.”

The soundtrack recording, thus far released digitally, is only marginally better. The spatial audio version on Apple Music is a soupy sonic mess. The CD-resolution version I was able to download on Qobuz is better but crude in comparison to Dudamel’s L.A. Phil recordings, and it does him and his orchestras (the New York Philharmonic and Los Angeles Philharmonic are used) a disservice. Divorced from the film, the singing is seldom distinctive other than Moreno’s “Somewhere,” which is simply hard to take divorced from the film.

If opera can do no better, where does that leave us? Musically, the most satisfying “West Side Story” performances I recall have been concert ones with Michael Tilson Thomas conducting the San Francisco Symphony and Dudamel leading the L.A. Phil at the Hollywood Bowl.

There is another option, though, and that is to treat “West Side Story” with the irreverent spirit that was so promising when Bernstein made his operatic recording. Barrie Kosky has miraculously done just that at the Komische Oper in Berlin.

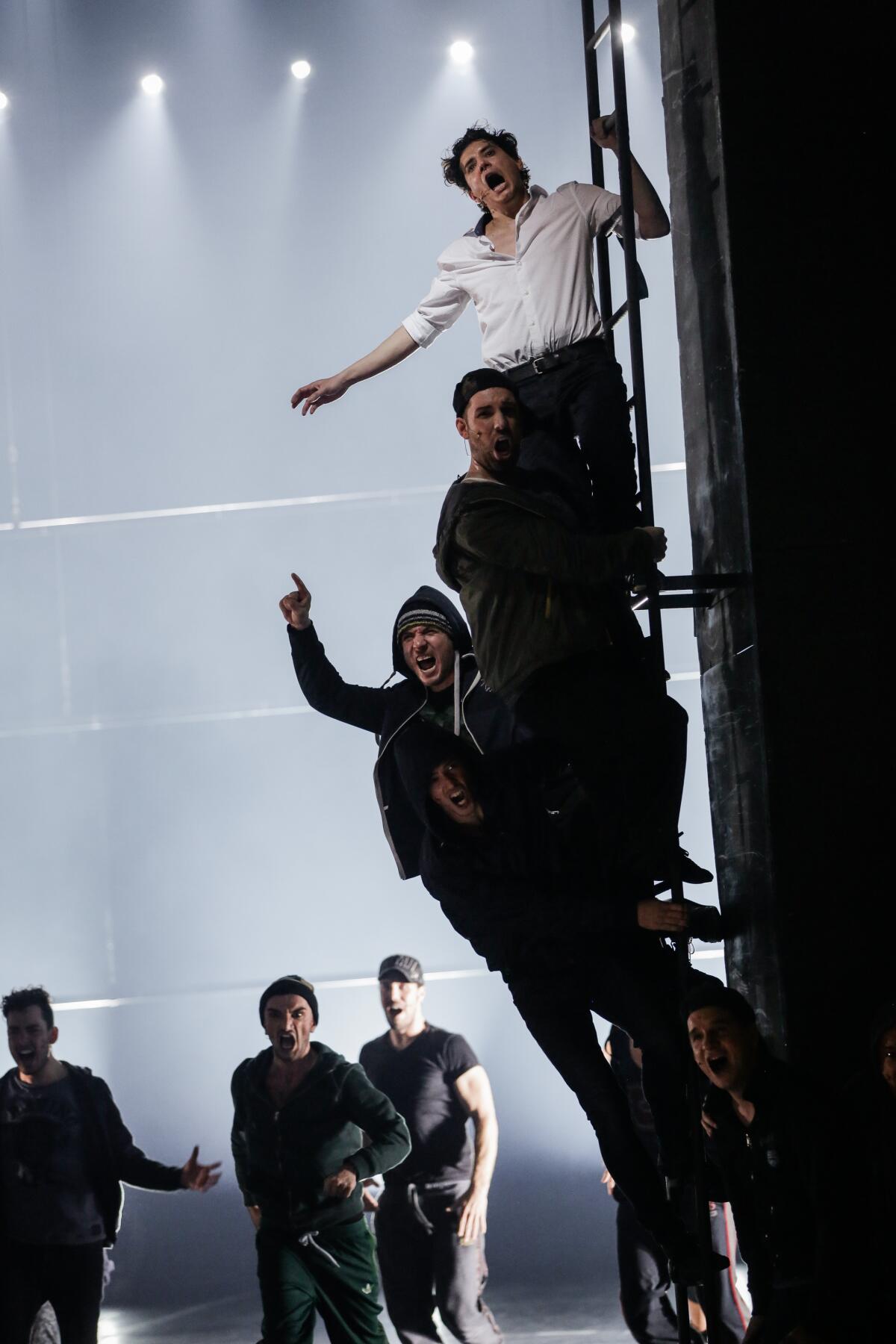

First seen in 2013, his production breaks seemingly ironclad “West Side Story” rules. The songs are sung in English, but the dialogue is in German for a German audience. There is no set, just vast quantities of presumably toxic stage fog. You can’t tell the Jets and the Sharks apart; everyone looks the same (most are German performers) and dresses the same. There is no Upper West Side and barely even a balcony. Fabulous costumes are kind of punk but neither place- nor time-specific.

Instead, there is nothing but unfiltered and often flamboyant theater. The characters are trapped in a social prison neither they, nor we, can see, just sense. Escape might be just around the corner were it not for the bleak fog blurring their vision. Their identities are blurred as well. Their enemies are not each other but their environment. The cast I saw three years ago dazzled. Music drove their every move, emotion and utterance. Otto Pichler’s dance is a totally new, vital reinvention.

Broadway required “West Side Story” to end with a glimmer of hope. Maria stands over the body of her beloved and berates the gangs. Unnerved enemies together carry Tony away as “Somewhere” shimmers in the orchestra. Spielberg milks it effectively. At the Komische Oper, the gangs remain apart. “Somewhere” is not in front of us but somewhere else, nowhere. We’re all blinded by the fog.

Kosky’s “West Side Story” was supposed to come to Los Angeles Opera during the 2018 centennial celebrations of Bernstein’s birth. Union regulations forbade the fog, and the whole thing was scratched. Instead, we now have a new fog-free film of “West Side Story,” with its insufficient promise of clarity.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.