- Share via

One of the most searing artistic experiences I’ve ever had came courtesy of Alison Saar in 2017. The Los Angeles artist was part of a group show of Black female sculptors titled “Signifying Form” at the Landing gallery in L.A.’s West Adams district, organized by independent curator jill moniz.

The show was memorable all around. But Saar’s piece, in particular, floored me. The nearly 7-foot-tall sculpture titled “Cake Walk,” from 1997, presented a larger-than-life marionette of a Black woman that the viewer can control via a system of pulleys. The title references a processional dance that originated on Southern plantations during the slavery era and would later be parodied by white performers in minstrel shows. In Saar’s piece, a firm tug on the pulleys could make the figure dance.

On the one hand, it’s an irresistible work. Saar invites the viewer to touch a work in a place where touch is usually forbidden. It’s also one that left me feeling queasy. To engage the marionette is to engage the manipulation of a vulnerable Black woman’s body (she is nude). It is also to engage a whole legacy of manipulation and control over Black women.

It’s a piece I haven’t stopped thinking about since — just like I haven’t stopped thinking about many of Saar’s other potent works: sculptures, drawings and paintings of Black female figures who may be vulnerable, yet are also intent on reclaiming their agency. In a 2018 solo show at her longtime gallery, L.A. Louver, the artist created a series of works inspired by the character of Topsy from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” which took the stereotypical uncivilized wild child from the book and transformed her into a potent symbol of Black female force.

A sculpture survey shared by two Los Angeles art museums

There is a lot more where that came from. And some of it is on view in an ongoing two-part survey, “Alison Saar: Of Aether and Earthe,” at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College. Sadly, “Cake Walk” is not on display, reflecting the need for a comprehensive retrospective devoted to this important artist. But the shows nonetheless offer a broad overview of Saar’s work, which, in deft and profound ways, has engaged myth, spirituality, history and the physical and psychological states of women.

Saar, 65, who is mixed race, hails from artistic lineage. Her mother is Betye Saar, an icon of the Black Arts Movement, and her father, Richard Saar, who died in 2004, was a ceramicist and conservator. Now that her two children with husband Tom Leeser (also an artist) are grown, Alison says she has found her art evolving.

“The work started becoming more political,” she says over a cup of tea in her Laurel Canyon home. “The work was always political, but with Black Lives Matter, more so.”

This month, Saar added an outdoor sculpture to her show at the Armory: “Catfish Dreamin’,” which resuscitates an early public work that she first staged in Baltimore in 1993. The installation is accompanied by an online component, which features digital works by her and other artists that draw from watery themes. In addition, Saar has been busy organizing a group show, “SeenUNseen,” which will land at L.A. Louver in November and focus on artists, she says, who serve as “mediums with the spirit world.” All of this is in addition to the public commission she is working on for Destination Crenshaw, a monument to the culture of the neighborhood.

In this conversation, which has been condensed for space and clarity, Saar talks about how being a mother has been formative to her art, why touch is vital and what sorts of magic she thinks we could all use right now.

How has the pandemic changed the way you work?

Initially, just before COVID hit, we had traveled — we’d gone to China, we’d prepared for the Armory show — and I was ready to do nothing. I worked from home. I did some prints. I did small carvings. I had started these hot comb pieces [which feature a palm-sized carving of a woman attached to the teeth of a hot comb]. This is a scale I’ve never done before — with a whittling tool. My normal tool is a chainsaw.

Your pieces often feature a mix of incredible textures that almost beg to be touched. How does touch inform what you do?

They have these categorizations for how people learn and experience things — one is definitely tactile. I’m that way. My children suffer from the same thing. I remember going to the principal’s office for a meeting with my son, Kyle. He comes in and goes around the principal’s office and he touches every single thing. And she’s like, “This is the problem.” And I said, “This is not a problem. It’s the way he is.”

My father was a conservator so I know why you don’t touch. But some pieces, the more you handle them, the more patina they get. They show the accumulation of experience that they gain from being touched. That’s the frustrating part of showing in spaces like [museums]. So, I’ll make pieces that require touch. It’s how I learned to do things and it’s the work I’m attracted to.

How did watching your father work shape your view of material?

He worked on a lot of Tang Chinese stuff. That got me into colors, surfaces and textures. I then began working for Jan Baum and Iris Silverman at [Baum-Silverman Gallery on La Brea]. I was working on African stuff. That’s where I got into touch. There was so much stuff on the surface of those objects — libations, for example — from its purpose [as a ceremonial object]. And I was always interested in what was on the back sides of things and the insides of things.

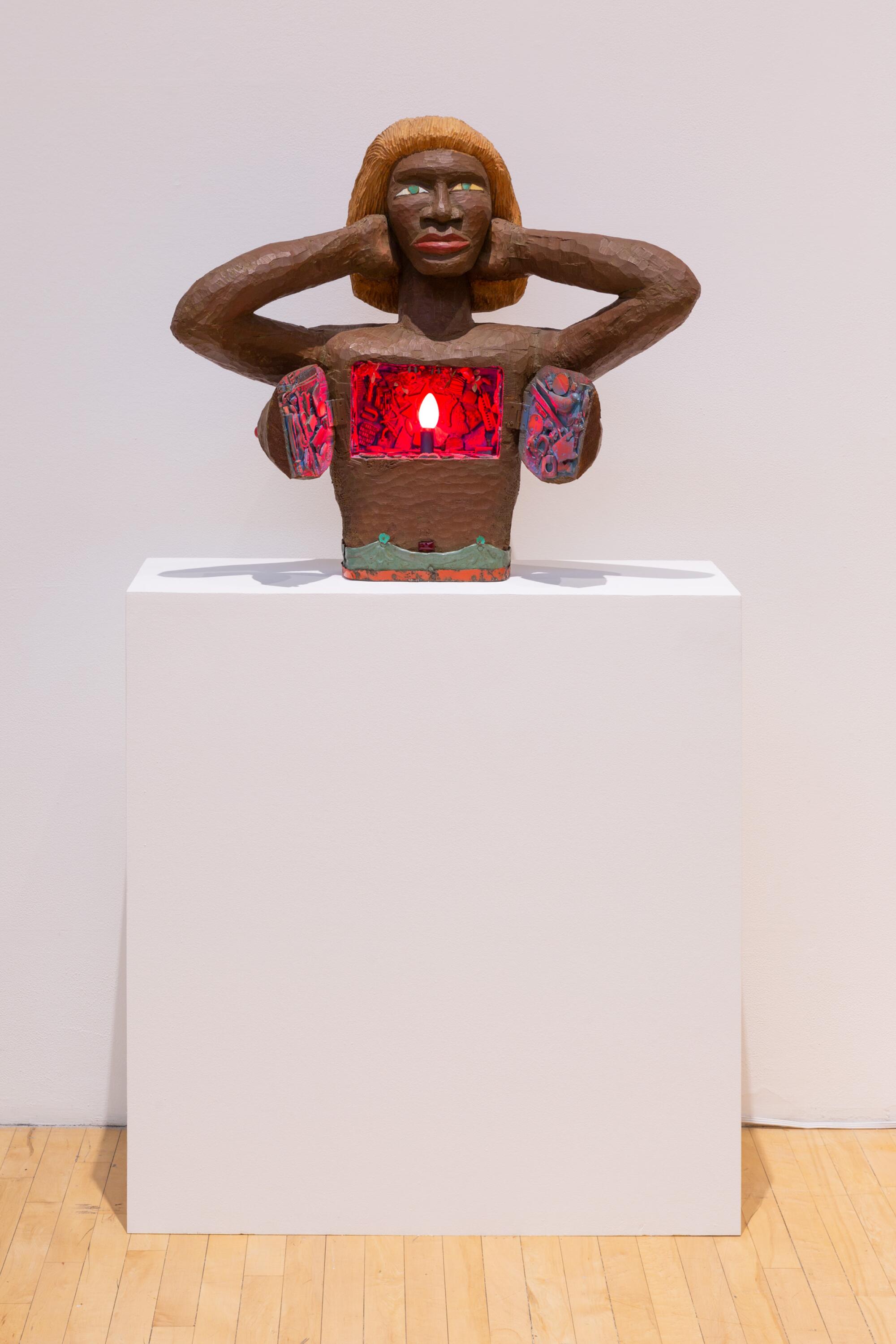

Women figure most prominently in your work. You’ve talked about “the incredible machine” of the female body. Why is that machine interesting to you?

Before having my first kid, that wasn’t necessarily the case. There were a lot of male figures and I was interested in the urban. I had my son and that flipped a switch. It’s so crazy, all of these things that happen: lactating and birthing babies.

That was also a point where, in anticipation of [motherhood] I made some early pieces, wondering who my child was going to be. [Children] have a certain experience and wisdom from the day they are born. They open their eyes and look at you like, “Who are you?” That made me interested in the soul and the spirit.

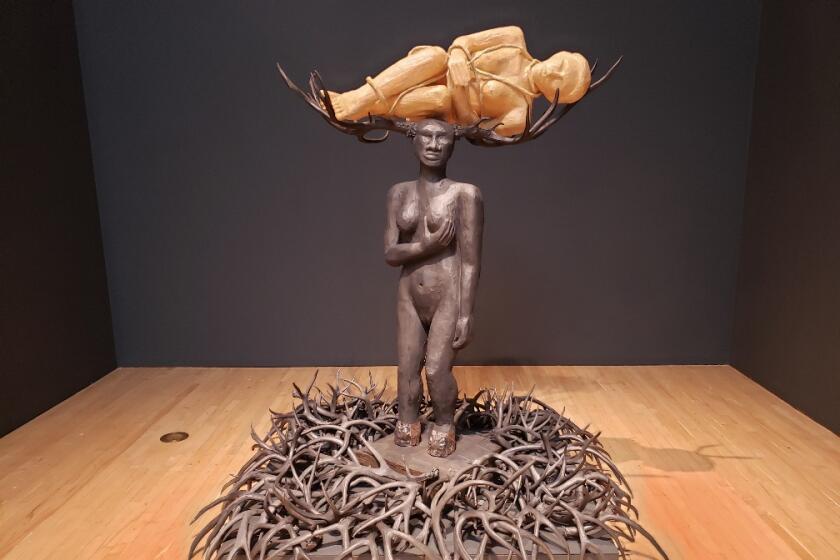

You can look at the work from 1989, when Kyle was born, and you can see where my role as a woman, as a mother, as a menopausal woman — you can see that progression. Now, no longer being menopausal and no longer having children, there was a weird free fall of, “Now what do I do? Who am I?” That’s what the piece “Rouse” at the Armory is about.

What made you want to take on Topsy from “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”?

It was a book that was written by an abolitionist, but even with her best intentions, she created this stereotypical figure. I started looking at Topsy when my daughter [Maddy] was 5. She posed for the first piece. That must have been ’98. At that point, I was really interested in [Topsy] being inquisitive and that felt very much like Maddy, who is very fierce and always questioning everything you ask her to do — always bucking the system. That’s what Topsy was.

Twenty years later I started looking at Topsy again. I was intrigued with her owning that she is fierce and some of that fierceness comes out of being abused, taken from her family. In that fierceness, there is resilience. She is ready to fight back. In Harriet Beecher Stowe, she complies. But I wanted to switch up that ending, where she continues to be this wild child.

That army of girls also came out of the Philando Castile shooting. In the tape, you can hear the daughter in the background. How did this happen with a child in the car? And it’s happened so many times. Who does she become? How does she experience this trauma?

I imagine her saying, “All of this happened, but I’m not going to be crippled by it. I’ll be stronger and fiercer.” I was wishing a happy ending for that little girl and all of these other children who have witnessed so much trauma.

You’ve made numerous works that reference floods. Those feel particularly poignant given the ravages of Hurricane Ida. What inspired them?

Watching [Hurricane] Katrina unfold [in 2005], you always thought, we’re in the United States, we have access to people who can help folks. But here, people were literally drowning in the streets. This, of course, was not the first time it was happening, but it still felt totally unbelievable. To see the disparity between those who had money to get out of town and those who don’t — and that’s by design because the area above sea level is owned and lived on by white folks and everyone else lives on the flood plain.

Kehinde Wiley and Alison Saar and are among the artists whose work will create a $100-million-plus cultural corridor celebrating Black L.A.

I started to look at the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Image by image ... if you look at Katrina, you see people standing on overpasses; look at Mississippi and you see Black people dropped off on levees who had to stay on the levees. It felt like it was the same. Here we are still living these racist policies that just continue.

In the Benton Museum installation, there’s a drawing of a woman paddling through floodwater and a sculpture of the same image. What comes first, the drawing or the sculpture?

They are usually sculptures first. I think of the drawings and paintings as studies of the sculptures. That’s why they look stiff. Sometimes I’m doing paintings and I could be doing anything, but it still looks like a kouros. I think the work is very influenced by colonial photography and these very posed sorts of situations, this discomfort in stillness and being told to stand and pose a certain way. It’s the stillness of being observed.

You created a monument to Harriet Tubman — the first public monument to a Black woman in New York City. How would you like to see monument design evolve?

There is an inherent problem with monuments because history changes. What history is worth maintaining and which histories need to be dispelled? I was interested in having a space where people could contemplate that. So there is a space where you could sit. There is a garden component.

The landscape guy, I asked him if we can do plants that exist between Maryland and New York. We did that initial planting and, of course, things aren’t taken care of and it died. Then someone came and planted, guerrilla-style, an abolitionist rose. And then a guy who has a community garden nearby, he came and planted cotton and he uses it as a place where he teaches kids about cotton. It’s incredible.

That’s what I’m interested in: a place where people can come together.

So monument design that gives space for the public to bring something to it.

Yes. I think that would be great. A spurring for other things.

Your work often engages elements of magic and ritual. What bit of magic could you use right now?

I set this Yemaya altar up at the beginning of the pandemic [gesturing at an altar that stands along one wall of her dining room]. I keep on thinking I should put it away. But then I thought, no, if I do that, she could get mad.

It feels like there needs to be some healing stuff going on. A cleansing is really necessary now because we are all burdened by this darkness and hatred. That’s what my “Hygiea” piece is at the Armory. It’s a cleansing.

"Alison Saar: Of Aether and Earthe"

Where: Armory Center for the Arts (145 N. Raymond Ave., Pasadena) and Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College, (120 W. Bonita Ave., Claremont)

When: Through Dec. 12 at the Armory and through Dec. 19 at the Benton Museum

Admission: Admission is free at both institutions; visits at both are by advance reservation

Info: armoryarts.org and pomona.edu/museum

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.