- Share via

When the Kusakabe family arrives at its new home during the opening scenes of Hayao Miyazaki’s beloved 1988 animated classic “My Neighbor Totoro,” oldest daughter Satsuki notices a camphor tree towering over the forest next to the house.

She stops to take in the enormous tree before pointing it out to her younger sister, Mei, and their father. The lingering shot is an early clue that there is more to the tree than meets the eye.

Mei and Satsuki later discover that this tree is the home of the giant, furry spirit of the forest named Totoro — one of Miyazaki’s most recognizable characters.

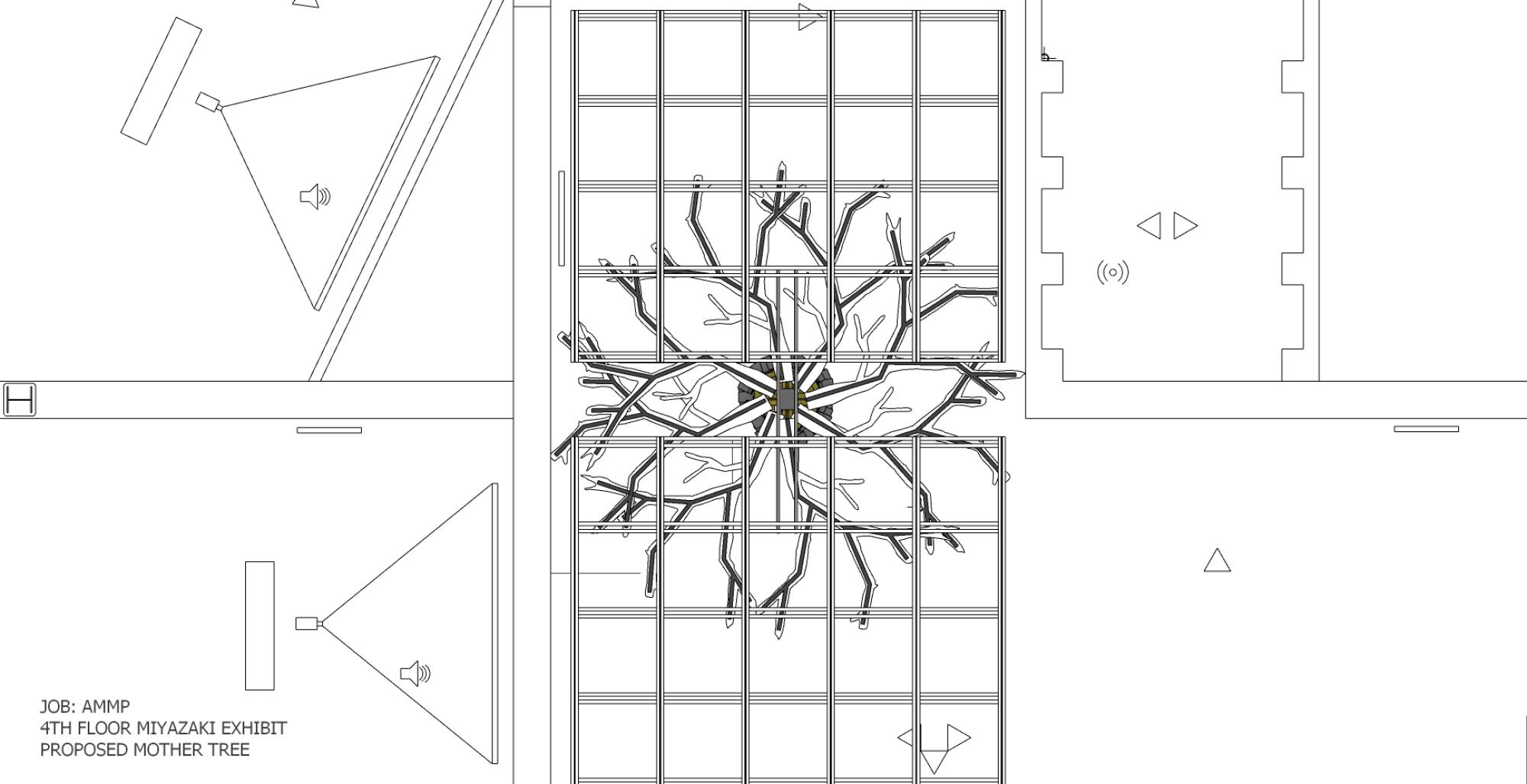

Inspired by the sequence that leads to Mei’s first encounter with Totoro, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures’ inaugural temporary exhibition, “Hayao Miyazaki,” features its own majestic tree. Called the Mother Tree — a massive, luminous installation that has been in the works for four years — will loom over visitors when the museum opens Sept. 30.

HBO Max launched with all but one Studio Ghibli movie in its library. This is the best order to watch them.

Academy Museum exhibitions curator Jessica Niebel organized this first North American museum retrospective of the acclaimed Japanese filmmaker with assistant curator J. Raúl Guzmán. Niebel always had envisioned this tree as part of the exhibition.

“I knew from the very beginning that I wanted to open this show with this Tree Tunnel experience,” Niebel said. Just as Mei travels through a tunnel of shrubs and trees, stumbles into a hollow at the base of the giant camphor tree and falls onto a slumbering Totoro, visitors will pass through the Tree Tunnel gallery into the museum’s world of Miyazaki: more than 300 objects, including pieces that have never been on public view outside of Japan.

Totoro’s tree, Niebel said, signals “where our journey concludes. So the Tree Tunnel experience and the [Mother] Tree are connected and linked and were the framework for the exhibition from the very beginning.”

A ginormous tree and Miyazaki’s connection to nature were among the ideas Niebel and Guzmán brought with them when they first met with Shraddha Aryal, the Academy Museum’s vice president of exhibition design and production, who oversaw the design of the retrospective.

“I find that first phase the most exciting in terms of design, because it is one of the hardest things to do,” Aryal said, “to hear somebody vocalize their intent in words and try to fit that spatially, architecturally, to what that means for a visitor.”

Aryal described the Miyazaki exhibition as a “completely intertwined collaboration” between the in-house curatorial and design teams in which content and design were developed simultaneously. After listening to what was important for Niebel and Guzmán, Aryal came up with a floor plan that featured three design elements: the Tree Tunnel, the Mother Tree and the Sky View, an installation that also serves as an intermission for visitors as they look up toward painted clouds.

Rather than re-create specific scenes from Miyazaki’s works, these three elements are interpretations “on what it means to go through his [tree] tunnel, what it means to look at his sky and what it means to explore his tree,” said Aryal.

Revisiting “My Neighbor Totoro” led Niebel to notice the prevalence and the specific significance of stand-alone trees throughout Miyazaki’s works.

In “Totoro,” the camphor tree is what initially draws the father to the family’s future house. The deer-like forest spirit Shishigami’s small island in “Princess Mononoke” (1997), in which the film’s hero, Ashitaka, is taken to be healed of a mortal gunshot wound, also features a stand-alone tree. A lone tree stands tall beside the road that ultimately leads Chihiro and her parents into the spirit world in the Academy Award-winning “Spirited Away” (2001). And in “Castle in the Sky” (1986), the first feature of Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli, the floating island-city Laputa is essentially a giant tree.

After looking at reference images of trees in Miyazaki’s movies, it was important for Aryal that the designs for the installation moved away from these drawings because the purpose was not to create a replica of any specific tree. The Mother Tree is something more abstract.

The stand-alone tree marks important moments for Miyazaki’s protagonists, Niebel said. “They kind of herald these transformative experiences. … So [the Mother Tree] was inspired by Totoro’s tree, but it represents all the massive stand-alone trees that appear in Miyazaki’s films.”

One of Aryal’s goals for the Mother Tree, which rises right before visitors leave through a final portal, was to emphasize scale.

“You have to feel small in front of it, and you have to be immersed in this experience,” she said.

The result is a massive trunk composed of painted wood strips that are applied around an inner structure unevenly, to make it look more organic.

The Mother Tree’s ethereal nature is represented through its luminous canopy. Taking advantage of the open ceiling, Aryal and her team worked with exhibition fabricator Cinnabar on a ceiling grid covered with netting. White nylon string hanging through the net, along with green fiber optics that run through branches on the grid, create the willowy effect overhead. Theater lights provide the additional pulsing green glow that reflects off the floor, completing the magic.

Niebel said the Mother Tree, like the rest of the Miyazaki exhibition, is meant to be an invitation.

“The tree represents bigger philosophical ideas and [Miyazaki’s] belief that magical things can exist … the idea that there’s something more to trees — something magical about them,” Niebel said. “So we wanted to make a magical tree.”

And because of its size, “it is very much standing in your way,” Niebel said. “You can’t ignore it. You have to acknowledge that it’s there, and, hopefully, it makes you think about how you interact with these things, even outside of the exhibition.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.