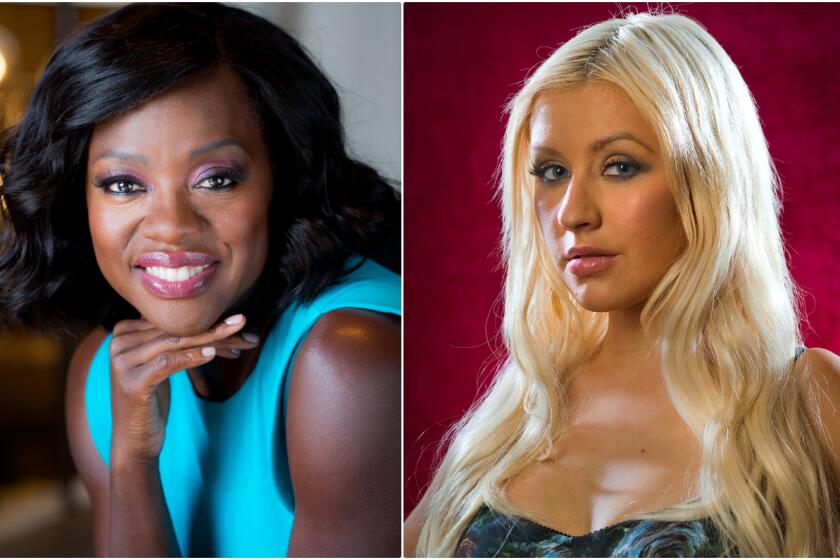

Review: Viola Davis and the L.A. Phil winningly connect ‘Peter and the Wolf’ to MLK

- Share via

By all appearances the Hollywood Bowl is big-time back. The first official night of the Los Angeles Philharmonic summer season Thursday was, in nearly all respects, a typical first night of the L.A Phil Bowl season.

Gustavo Dudamel conducted. A large crowd attended. The orchestra no longer provides an audience count (it never could be believed, anyway), but I’d make it easily more than 10,000. There were no requirements for masks, distancing, vaccinations or tests. Picnicking was nearly ubiquitous.

The program was meant to please widely. Viola Davis splendidly narrated “Peter and the Wolf.” Stirring pieces by the neglected composer Margaret Bonds and the great Duke Ellington paid tribute to Martin Luther King Jr.

Not only was this the first time that Dudamel and the L.A. Phil were able to perform before an everyday L.A. public since March 8, 2020, but Thursday also felt a world away from that first special Bowl program for a small, invited crowd of distanced, masked first responders exactly two months earlier.

Appearances, though, can be deceiving. At the time of that May concert, COVID-19 numbers were going down, with 247 cases reported that day in L.A. County.

Thursday, cases were more than six times that number. Were we kidding ourselves? Dancing on the edge of a volcano? The L.A. Phil has surveyed its audience and found an overwhelming majority are vaccinated. Everyone I spoke with felt safe but in slightly surreal surroundings.

Indeed, the mere hint of danger — rather like eating poisonous fugu fish from a reputable sushi bar in Tokyo — may well have added to the overall exhilaration of the evening. Even the chilly weather, just like it’s supposed to be in mid-July at the Bowl, felt like a throwback, the amphitheater somehow (and no doubt only for the moment) a climate-change anomaly in a world of heat domes and horrid European floods.

A kite festival in DTLA, a salute to Carole King’s “Tapestry,” Alonzo King dance, Judy Baca art. Your weekend options start here.

One thing missing is a printed program, surely no more a spreader than the other merch on sale, to say nothing of the food services. Conventional notes on the pieces played and bios of the performers can be found, with a little hunting, on the Hollywood Bowl app. But no pages for something about the intent of the program: In this case, an intriguing framing of civil rights-inspired music by populist Soviet Prokofiev.

It could be that the “Classical” Symphony, the curtain-raiser and “Peter and the Wolf,” which is Prokofiev at his most lighthearted and delightful, are enough. The symphony is the work of a pesky 25-year-old modernist composer tweaking the establishment by updating a Haydn-esque symphony with modern conveniences. “Peter and the Wolf,” written a decade later in 1936, provided the Soviet Union with its most engaging propaganda.

Feckless Pioneer Peter is the model of Soviet youth, a conqueror of nature, presented in the guise of teaching children about the instruments of the orchestra. Tempered, as with the “Classical” Symphony with wit and sophistication, as well as Prokofiev’s sensation sense of theater, we’re hooked.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

How does this connect with King? One could look to a racial idealism, at least in theory, in Communism, the striving for a communal society. On some qualified level, the finest music of both the Soviet Union and the civil rights movement focused on the struggles of the oppressed, meeting in a genuinely important, and often controversial, high art.

Vague though these notions seemed in the program-making, they mattered in performance. The “Classical” Symphony became a here-we-are moment. The trickster symphony sneaks up upon you like the cat in the “Peter and the Wolf.” Dudamel made it look easy, but under the hood was a complicated musical machine finely tuned. Two months ago, at the Bowl, you could sense the L.A. Phil tuning up for a fight with its environment. Now, fully fit, the orchestra has regained its hometown sparkle.

“We tried to make music with some distance,” Dudamel told the crowd, referring to the pandemic “Sound Stage” streams from the Bowl. Looking around at the vast acreage on stage and off, he added, beaming, “Nothing compares with this.”

The main King tributes were excerpts from Bonds’ “Montgomery Variations.” Herself a pioneer, a Black composer from Chicago, she became a member of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s through her friendship with Langston Hughes, whose poems served her in song and oratorio. After Hughes’ death in 1967, she moved to L.A. where she remained for the rest of her life, becoming known mainly for her arrangements of spirituals.

Zubin Mehta led the premiere of her “Credo” for chorus and orchestra with the L.A. Phil shortly after her death at 59 in 1972. She was, though, quickly forgotten and is only now beginning to be rediscovered.

From the little evidence of her music yet available, her Hughes songs may be her most lasting legacy. (Soprano Julia Bullock will include Bonds in her Bowl repertory Sept. 2.) The four “Montgomery” variations Dudamel chose — “Decision,” “March,” “Dawn in Dixie” and “Benediction” — each, in its own way, brought a different glow to the spiritual “I Want Jesus to Walk With Me.” For Bonds, walking with MLK was walking with Jesus.

Dudamel followed that with the “Martin Luther King” movement from Ellington’s “Three Black Kings” suite. This had been on the last concert the L.A. Phil gave before the pandemic shutdown, as part of the orchestra’s Power to the People! festival. Ellington’s MLK doesn’t walk, he glides on air, a graceful ghost who lifts us up with him. Dudamel dedicated the performance to Guido Lamelli. The longtime L.A. Phil violinist died Tuesday.

Who hasn’t narrated “Peter and the Wolf”? Peter Ustinov, Sophia Loren, Romy Schneider, Captain Kangaroo, David Bowie, Eleanor Roosevelt, “Weird” Al Yankovic and Mia Farrow are on a long list of those who have recorded it. Even so, there remains every reason to bring Davis and Dudamel into the studio for yet another. Without fuss or exaggeration, the celebrated actress was on mark with a clever subtle edge, finding the precise fraction of satire in her inflection to make sure we couldn’t confuse 2021 Hollywood with Stalin’s Russia. For Dudamel, every instrument, not just the flute/bird, clarinet/cat, bassoon/grandfather became a living being.

“We made it!” Dudamel exclaimed when he first addressed the audience. “Peter and the Wolf” was the sound of making it: the playing, the narration and amplification, the whole ball of wax. Were it the whole ball of vax, this “Peter” might truly serve as a Prokofiev-ian Young Pioneer, ever the clever, invincible dominator of nature.

In exchange for loaning ‘The Blue Boy’ to London, the Huntington is negotiating the loan of a monumental painting by Joseph Wright of Derby.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.