He died homeless and forgotten. Now gay Black composer Julius Eastman finally gets his due

- Share via

The growing Julius Eastman revival throughout the new music community in the past few years seems, particularly from hindsight, inevitable. It would be hard to find an artist who personifies so many issues of our day — Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ rights, homelessness, income inequality, mental health, addiction, you name it.

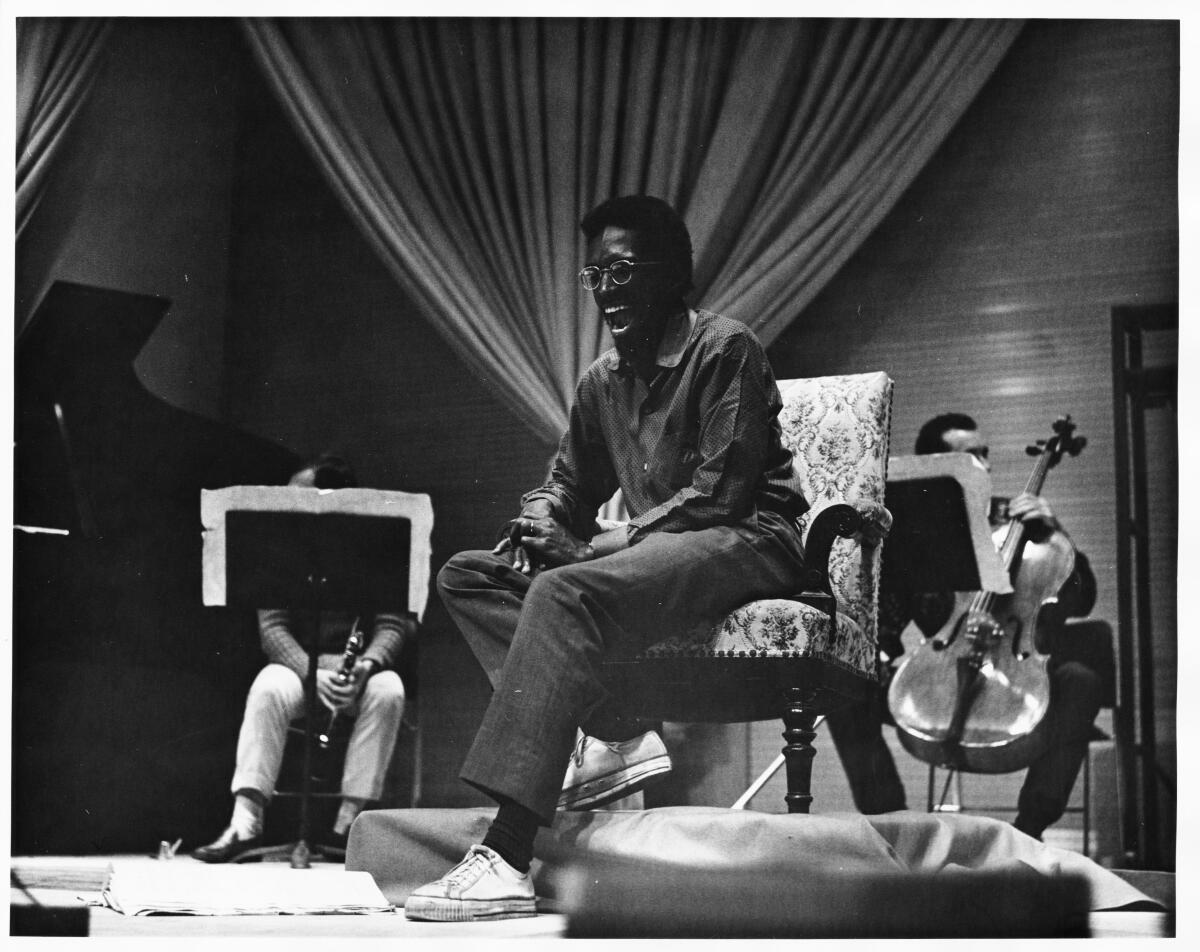

An extraordinarily gifted composer, vocalist, pianist, dancer and choreographer, Eastman had a magnetic presence and gripping sense of theater. He was proudly and provocatively Black and gay. He could be — personally and in his art — lovable and discomfiting. It didn’t matter whether you were white or Black, straight or gay: He had something up his sleeve for any of us. No one got off easy with Eastman. Whether through the shocking titles for many of his pieces or his relationships with lovers and cherished colleagues, he challenged so many forms of prejudice.

Eastman, who was born in 1940, rose like a comet with spectacular flair and flamed out just as stunningly, dying at 50 in obscurity — homeless and alone. His music — what is left of it (much is lost, all of it a mess) — requires Herculean reconstruction efforts. His life is a documentary or biopic waiting to happen.

Ever alien and alienating, the inscrutable Eastman has seemed destined to remain a new music outsider. He is simply too difficult and disturbing. Comets come and comets go. Or do they? In a remarkable series of events, the Eastman revival has taken a surprisingly trendy turn.

The Los Angeles new music collective Wild Up released a sensational recording Friday on the New Amsterdam label of Eastman’s seriously challenging, incessantly repetitious 1974 “Femenine.” The majestic effusiveness of this performance is such that it instantly changes the landscape, revealing new possibilities for a far and wide acceptance of Eastman’s music.

This comes on the heels of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s announcement of a free chamber music program combining Eastman with the popular Estonian spiritual minimalist Arvo Pärt at the Ford on Aug. 3. Two weeks later, Eastman will be paired on a program with another Eastern European mystic minimalist, Henryk Górecki, at another festival, the Proms in London.

Most unexpected of all has been the news that the New York Philharmonic will give the first professional performance of Eastman’s disquieting Symphony No. II — “The Faithful Friend: The Lover Friend’s Love for the Beloved” — found in a drawer and reconstructed. The symphony will be part of a regular subscription concert series in February that will be conducted by the orchestra’s music director, Jaap van Zweden, and that opens with Beethoven and Berlioz.

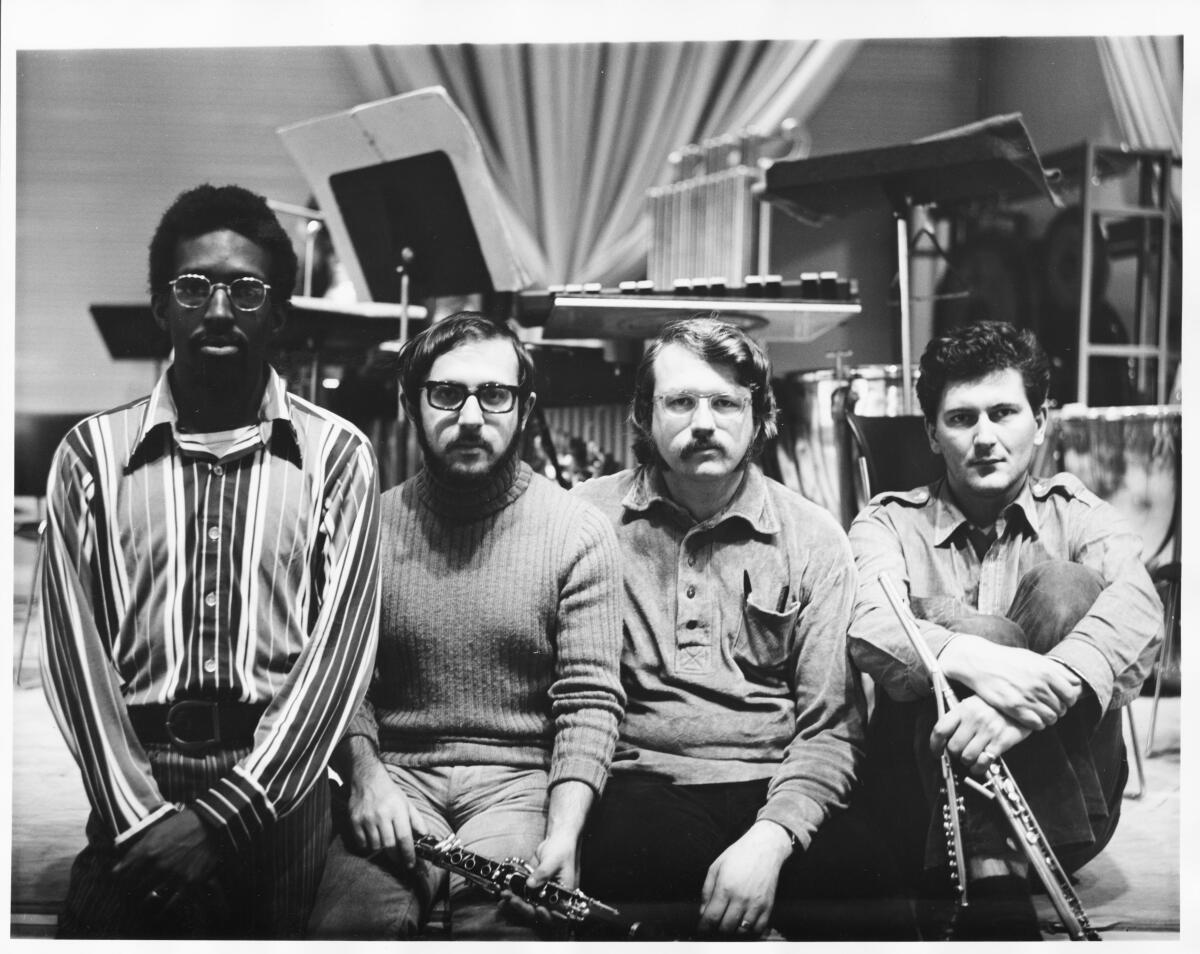

But back to “Femenine,” which some members of Wild Up performed three years ago as part of a Monday Evening Concerts ensemble and which Wild Up presented Thursday night outdoors at Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa to promote the new release. It was written during Eastman’s most promising years, when he was a member of a flourishing new music scene at State University of New York’s Buffalo campus. Eastman — who grew up in Ithaca, N.Y., and attended the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia — was turning heads wherever he went and whatever he was doing.

He was an extraordinary vocalist who sang in the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s new music series under Zubin Mehta. He appeared with Pierre Boulez and the New York Philharmonic. He was nominated for a Grammy for his compelling performance of Peter Maxwell Davies’ “Eight Songs for a Mad King.” He toured Europe to stamping, cheering crowds with a work, “Stay on It,” that gave the formalist minimalism of the moment an irreverent jazz-pop-improvisation kick in the behind.

“Stay on It,” which also has a gripping recent recording from another L.A. institution, Jacaranda, had been Eastman’s breakthrough. He aggressively pummels a melodic figure with a ferocity that intimates a session of unbearable irritation. Instead, though, he breaks down your defenses with glorious effusions of new material, opening you up to what becomes a new kind of musical spirituality.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

“Femenine” takes that process further. It was originally part of a duality, with “Masculine” played at the same time, but that is one of Eastman’s many lost scores. At one time, when living in New York, he was evicted from his apartment for not paying the rent. He never bothered to collect his scores. He didn’t bother with possessions or, often, necessities. He was on a messianic and ultimately self-destructive mission.

The documentation we have of “Femenine” is an extremely sketchy score and an archival 1974 recording by the S.E.M. Ensemble, of which Eastman had been a member. Not much is known about that performance in Albany, which included local students. At the premiere in Buffalo a year earlier, Eastman prepared and served soup during the performance and wore a dress.

An awful lot is left to the performers to figure out. There is leeway in the instrumentation and number of performers. Putting a performance together requires the kinds of creativity needed to realize a jazz chart or a medieval manuscript. It has to be recognizably Eastman, but it also has to have a performer’s identity.

Wild Up, led by Christopher Rountree, adds a narrative that you can use to follow its performance, giving titles to 10 sections of “Femenine,” such as “Create New Pattern”’ “Be Thou My Vision” and “Pianist Will Interrupt Must Return.” Take ’em or, as I prefer, leave ’em.

This is not the only recording of “Femenine.” There are a few now, and all are bold and powerful. Wild Up, however, goes beyond all the others in capturing the sheer expansiveness of Eastman’s music. The repeated rhythmic tick that begins everything and never quite goes away is heard here as an invitation to dream. It is the sound of stepping out of yourself.

What that means, what follows (and, boy, does a lot follow) is not for me to say but for every listener to find out individually. It’s the search that matters. And that leads to maybe the most shocking aspect of the shocking Eastman. His search for self and spiritual transmigration led to his downfall and has to become a cautionary tale.

Eastman may have been welcomed for being a gay Black man in a mostly white, if sexually fluid, new music community, but that only seemed to underlie his outsider status. To be personally accepted wasn’t the point. For Eastman, an anodyne new music culture that prided itself on functioning outside of personal identity is what needed changing.

I remember Eastman well when he worked at the downtown Tower Records in New York in the late 1980s. I lived in New York and regularly ran into luminaries who came to hang out and schmooze with Julius. The Julius I encountered was a sweet man, angelic even.

But angels are all-seers. Eastman proved brutally direct and confrontational. He infamously titled ferocious pieces for multiple pianos with the inflammatory titles using the N-word (“Crazy N—” and “Evil N—”). He wanted there be nowhere to hide, and he left nowhere for himself to hide, either.

An essential resource on Eastman is the book “Gay Guerilla,” edited by Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach. In the book, Ned Sublette — Eastman’s close New York friend, a composer, guitarist and musicologist — perceptively remarks that “Julius was only on loan to the white music world.”

In the end, he was only on loan to the world. He didn’t fit in anywhere. He ultimately alienated pretty much everyone. He seems to have been beyond help. In a small way, I tried. I told him his music needed to be heard. He needed recordings. I introduced him to a publisher who took an instant interest. As a contributor to the Wall Street Journal at the time, I suggested writing a profile of him in hopes of bringing his work and his story to a broader audience than that of the Village Voice (or occasionally the New York Times), where he might be reviewed. He said sure but no doubt smelled trouble.

Then he disappeared. No one knew what had happened to him. A year later we learned that he had died of heart failure, half starved, refusing help.

It is now up to us to piece Eastman and his music together. Wild Up’s “Femenine” is a revelation. Hearing it is like hearing Terry Riley’s “In C” for the first time. It has what it takes, in any just musical realm, to become a popular sensation. It is also the first of what will be several Eastman New Amsterdam recordings by the ensemble. The comet is back in sight and maybe for good.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.