Art museum endowments soared in the pandemic. So why sell art to pay the bills?

- Share via

When the COVID-19 pandemic erupted last year, predictions were dire for how shuttered art museums might fare in the coming storm. Fourteen months later, many seem to have lucked out.

One silver lining, largely unreported, has been a sharp rise in endowments — the banked funds whose income supports museum operations. Surprising, often double-digit, increases have reached as high as 40%.

Forty percent! Call it the pandemic dividend.

Against this consoling, unexpected windfall, however, a discouraging development has been unfolding. At least half a dozen museums have turned to selling art from their collections to pay bills. That dispiriting practice has long been forbidden.

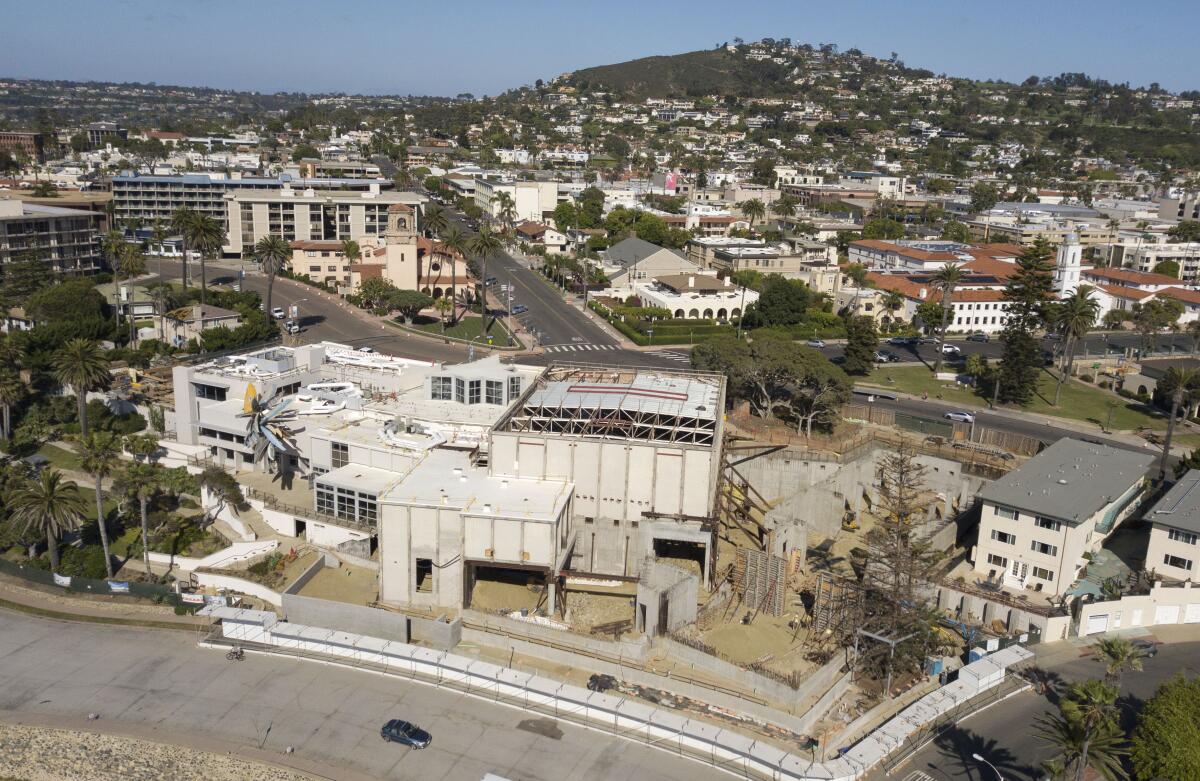

One example: Last month, the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego sent nine paintings and one sculpture from its collection of about 5,900 works to auction in New York. When the hammer fell May 14, noteworthy examples by Roy Lichtenstein, Conrad Marca-Relli, Lorser Feitelson and six other postwar American artists had been transformed from paint, canvas and stainless steel into nearly $900,000 in cash.

A museum news release explained that monetizing some museum art was necessary to “help stabilize collection care efforts in these times of economic downturn.”

Did it? More important, was it necessary? Has the upheaval caused by the cruel COVID-19 pandemic destabilized essential care of art collections, which is a museum’s most basic institutional function?

The likely answer is no.

Forty percent growth is what MCA San Diego endowments witnessed year over year since the pandemic began, rising by a startling $14 million. Almost none of the gain represented gifts, according to a museum spokesperson. On average, the museum earned more each month through routine investment than it did by unloading all that irreplaceable art at auction.

It was not alone. MCA San Diego was at the high end of a phenomenon repeated at art museums across Southern California — and no doubt elsewhere. I approached half a dozen museums, large and small and in different locales, to get a sense of how endowments had fared year over year.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art saw its endowments rise by 37%. The city’s Museum of Contemporary Art witnessed 23% growth.

The Palm Springs Art Museum jumped 20%, not including income from its own controversial sale last year of a monumental Helen Frankenthaler painting. The mighty Getty Trust grew 10%, packing $700 million onto its $7 billion in endowments. At UCLA, the Hammer Museum’s funds expanded 9%, just missing double digits.

On average, the gain was almost 24%. Setting aside the Getty behemoth — always an outlier in discussions of cultural finances — the five art museums in my unscientific regional sample together have about $104 million more in their coffers today than a year ago.

For endowments, that’s pretty much the opposite of an economic downturn. And if economists in the new UCLA Anderson quarterly forecast are correct, things look promising going forward. The pandemic dividend should continue.

Nonprofit institutions typically make conservative investments, which generate modest yields. Market indexes had gone into free fall in March 2020, but since then the Dow rallied, climbing 12,000 points, and tax laws were tweaked. Robust endowment performance has been one bright spot for art museums amid the pervasive gloom of the past pandemic year.

That doesn’t mean that they are rolling in dough, of course. It does mean that epic catastrophe across the sector, widely predicted, did not materialize.

Museums typically fund operations from three sources — earned income plus annual giving, as well as from drawing on endowments. (A common draw is 4% or 5%.) When the pandemic forced museum closures for months on end, earned revenue from memberships, restaurants, shops and the like plummeted. Annual giving became a looming question mark as competing social service demands widened at other charities across the nation.

So as museums across Southern California reopen, things may not be entirely rosy. But together with lowered operating costs during closure, partial compensation from healthy endowment performance has helped mitigate what could have been a doomsday scenario.

Disappointingly, however, that silver lining has been tarnished by an unconscionable rush to the auction house by numerous museums eager to take advantage of a very bad decision made last year by the Assn. of Art Museum Directors. To ward off expected catastrophe, AAMD hastily relaxed a fundamental prohibition against using income from the sale of museum art to pay for museum operations, which includes collection care.

For a period of two years, the customary ban was lifted for museums that found themselves in extremis, unable to care for their collections. That panicked green light has been a disaster.

Multiple museums immediately pushed the boundaries of the AAMD’s poorly crafted pandemic response, ignoring the relaxed rule’s palliative intent. Instead, they’ve seen it as a brief window of opportunity for some fast cash.

New Jersey’s Newark Museum of Art is the most scandalous recent example. Its important 1846 landscape, “The Arch of Nero,” by the great American Romantic painter Thomas Cole, was among several works dumped at the spring auctions.

Cole’s crumbling ancient castle tower atop a ruined Roman aqueduct conjures the decadence of empire. The apparent metaphorical content — a warning as the westward-pushing United States invaded Mexico in 1846, roiling the slavery dispute on the way to Civil War — forms an eloquent historical backdrop to understanding today’s powerful Black Lives Matter movement. The painting would seem to be especially relevant to residents of a Black-majority city, but now, after 64 years hanging on its walls, it’s gone from Newark’s art museum.

AAMD’s cautionary words in announcing the temporary rule change — that it was “not intended to incentivize” the sale of museum art — seem impossibly naive.

Perhaps tellingly, the director of every museum that jumped onto the monetizing bandwagon is a specialist in contemporary art, where the market is the liveliest. None is a historian of earlier painting, sculpture or other global art. Their generation was raised speaking the neoliberal language of the primacy of the commercial marketplace, which arose in the 1980s and dominates art life today.

When the terrifying health crisis erupted, a discredited doctrine once shared by the likes of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan reared its ugly head. Privatized public resources were proposed as the best, most immediate answer to looming social problems. (Thatcher, doing her best Ayn Rand imitation in the face of her own calamitous economic recession, had likewise proposed that her nation’s art museums sell some masterpieces to stay afloat; she was ultimately rebuffed.) AAMD essentially followed suit.

Even now, as the COVID-19 pandemic wanes and art museum endowments wax, the hapless directors’ group has not fixed its fatally flawed prescription, which remains in place for another year. (It has no plans to, either, according to a spokesperson.) In March, trustees at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where a search for a new director is underway, amended its guidelines to conform to AAMD’s relaxed rule, eliciting a shudder of concern across social media that sales from its collection might be in the offing.

Frankly, I’ll be shocked if the fall auctions don’t feature more museum art.

The fatal flaw in the relaxed rule is that it turns a museum’s collection into a financial asset, contrary to established charitable practices. No museum in America carries its collection as a financial asset on its tax returns — and for good reason: In common law, no charity may own corporate property.

Tax-exempt museums don’t own the art in their collections; the public does. Museums are instead nonprofit stewards of a public asset.

The AAMD surely had the best intentions for protecting those assets, but it ended up needlessly pushing assets out the door. In a panic, what was then the leading professional group in the art museum field threw the fundamental principle of stewardship under the bus.

Turns out it didn’t need to. Performance of museum endowments — an actual, existing financial asset, rather than a made-up one — has offered unexpected help.

And I don’t just mean because museums will have a bit more principal in the bank on which to draw. If the MCA San Diego took a 5% draw on the $14 million its endowment gained so far, that would be $700,000 — a tidy sum, but still less than the total income from the art the museum unfortunately chose to sell.

Instead, here’s a better solution: Cash in the pandemic dividend.

How? Suppose a museum facing fiscal woes figured out how its endowment performed on average annually over, say, the previous five-year period, before the cruel pandemic turned life upside down. The same percentage gained during the pandemic year could be dedicated to augmenting the endowment principal, just like always.

But the difference — and this is the dividend part — between that prior average and the exceptional growth since 2020 could be made available as a cash reserve fund. The unexpected windfall could be applied to emergency needs.

With the pandemic dividend, millions of dollars would be on hand for museums to use as they see fit, without a raid on the collection. It could be spent toward: hazard pay or straight remuneration for beleaguered or furloughed staff, conservation or purchases of art, upgrades in gallery ventilation systems or expanded digital infrastructure for online programming.

Or, if the museum chose, leave some or all the exceptional gain alone, keeping it as a welcome addition to endowment principal. The Palm Springs Museum, for example, is terribly underfunded; a pre-pandemic endowment of just under $15 million is less than a third of what it needs to sustain its annual operating budget, according to numbers provided by the museum. That’s bad, but it’s not a crisis caused by the public health emergency.

Legally, endowments can be complicated. Some are restricted in their uses, others are not. Different states have different laws. The percentage of annual draw can be limited, uses of principal proscribed.

In general, though, most are designed to keep the principal amount safely intact while income is spent on charitable purposes. Given the extraordinary social and cultural trauma brought on by the pandemic, a state attorney general would be unlikely to come down on an art museum that was trying to maintain a public asset under unprecedented stress, especially if the historic value of the principal were being maintained.

When L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art got in trouble with the state of California a dozen years ago for spending down its endowment principal, the issue was charitable mismanagement during ordinary times. A pandemic dividend is not that. These times are extraordinary.

In the past, museum endowments were untouchable. Until now, so was the art collection. If AAMD wants to make itself useful, and perhaps restore some of the luster lost in its relaxed-rule fiasco, it might craft a window of opportunity around endowment uses that could pass muster during a crisis, one that has had a terrible effect on life in every state.

During this awful crisis, after all, doesn’t everyone agree it’s best to give priority to protecting the art, which is the reason the museum exists, rather than sheltering the money?

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.