As we return to normal, a new plague: stage fright in the theater of daily life

- Share via

Invitations are starting to arrive, via text and email, for dinners, birthday parties and weekend trips. But rather than being filled with excitement, I’m ashamed to say I’ve been experiencing waves of dread.

A few fellow vaccinated friends have confessed similar anxiety about resuming social life. Of course, there are lingering concerns about virus variants and the large number of people who still aren’t fully protected. The country is hardly out of the woods, despite considerable progress.

But the ambivalence many of us have about the lifting of lockdowns is more psychological than epidemiological. We’re simply not ready.

Yes, the pandemic has stretched on interminably. But give us a few more months to get ourselves together!

In my official capacity as theater critic, I’m prepared to make a cultural diagnosis. As the pandemic shows signs of coming under control in the U.S., an epidemic of stage fright is exploding.

The sociologist Erving Goffman wrote an influential book in the late 1950s that essentially confirmed Shakespeare’s proposition that “all the world’s a stage.” In “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life,” Goffman uses the idea of theatrical performance as a framework for understanding our social lives.

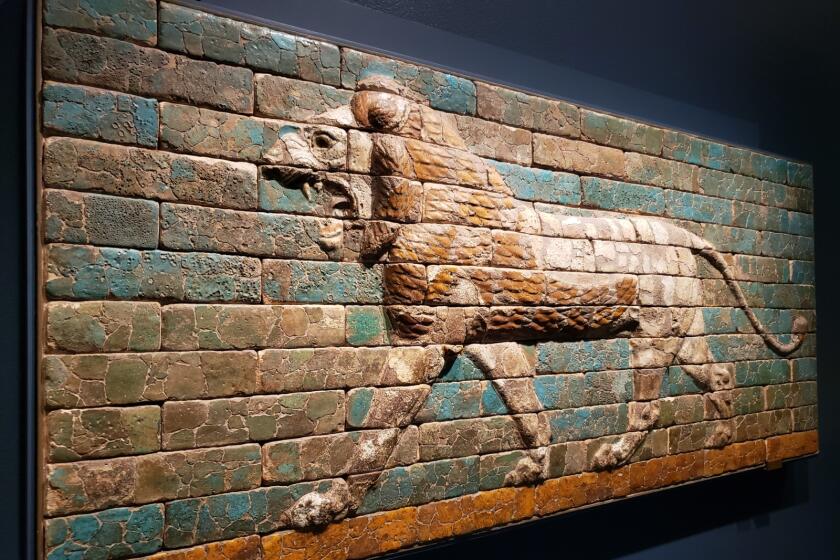

The Getty Villa ends its yearlong pandemic closure on Wednesday. On view: “Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins,” which goes back to the beginning, sort of.

This isn’t a book about how lives imitate art. Goffman’s focus is on the way we stage collective reality. In a nutshell, whenever we’re in the presence of another person, we play a role. It could be performer, fellow cast member or spectator, but there’s no getting around the inherent theatricality of daily life.

Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am” becomes in effect for Goffman, “I act, therefore I belong.” Social reality, in his formulation, is an ensemble effort. An individual “projects a definition” of a situation when he enters the company of others and this projection provides “a plan for the co-operative activity that follows.”

A good share of this performance work involves impression management, the control of how our traveling vaudevilles are received. Goffman inventories the myriad ways our public presentations can be undermined. Our fate as humans may be to wear a mask, but how easily they slip from our faces. No wonder we’re so nervous about bungling our entrances, missing our cues and flubbing our lines.

Security comes in part from establishing the spatial parameters of a scene. Workplaces have playing areas and backstage regions. Different zones call for different conduct, reflecting an organization’s mutually agreed-upon rules and hierarchies.

Gossip is permitted in the lunchroom, but not outside the boss’ door. Corridors, a liminal space, are ideal for eavesdropping, making them a temptation and a trap. Bathrooms, a point of awkward convergence, can quickly turn into a Bermuda Triangle.

For those who have been working from home for the last year, re-navigating this geography might seem as burdensome as having to don pants with buttons again or restart an unpleasant commute.

Goffman is aware that a great deal of what we know about one another is obtained by inference. Being on public display, therefore, requires constant vigilance. Filtering our communication via email or Slack is a comparative luxury. Unconscious gestures — a flash of impatience, a hint of a smirk, an outbreak of yawning — can wreck a carefully curated image.

Zoom is exhausting because it never lets us forget we’re in front of a camera. But returning to the public stage after an extended hiatus is even more depleting. Lifting weights is nothing compared to wrestling those obstreperous facial muscles during a meeting. Our heart rates are no doubt higher when we’re making small talk than when we’re warming up on a treadmill.

Having been sequestered for as long as we have, we’re out of practice in the art of appearances. When eyes are canvasing the classroom or conference room, it’s not enough to be attentive. One should try to look attentive as well — or at the very least, not as bored as one feels. When a joke is told, we can no longer resort to a laughing emoticon but must trickle out some semblance of amusement, even if only a genial groan.

Sitting opposite our dear friend at a restaurant, we shouldn’t betray that his old problem, still impervious to outside advice, hasn’t grown more fascinating since we last dined out a year ago. For those whose politeness is ingrained, courtesy won’t be much affected by the social interregnum. But properly inflecting one’s gratitude so that resentments don’t build may take some finessing.

Being social animals, we are exquisitely attuned to one another’s moods. Like those flapping butterfly wings in Africa setting in motion monster hurricanes in the Caribbean, minor fluctuations in demeanor can turn a sunny interaction into a superstorm of antagonism. Like it or not, we are Geiger counters for slights, our minds clearinghouses for grievances.

Skipping through this field of landmines doesn’t seem so foolhardy when we’re in the groove of making eye contact. But we no longer have the confidence that we can wiggle out of our faux pas. A trip to the supermarket is all it takes to see how our skills have rusted. Social reality is a team effort requiring coordination and circumspection, neither of which is second nature anymore.

Re-immersion is the only answer, but it may feel like sink or swim in the coming months. Many of us will be doing the dog paddle to stay afloat. Existential doubts are unavoidable. After we’ve seen how much we can do without, it’s only natural to be skeptical about the return of former pleasures.

Psychologists have a word for this state of blankness: languishing. The remedy isn’t more isolation but community. “Hell is other people” only if, like the characters in Sartre’s “No Exit” from which the famous line derives, one is locked in a room with the wrong crowd for eternity.

It’s important to remember that, as Goffman notes, we’re programmed to work cooperatively. In the theater of life, hecklers are the exception, not the rule. Most of us try to put at ease whoever happens to be in the spotlight. The sight of someone fumbling for words can turn a spectator into a gentle prompter. To spare anyone unnecessary embarrassment, we’re adept at not seeing or hearing what we’re not supposed to see or hear. A sense of reciprocity guides our tact.

When someone “makes a scene,” it means that person is no longer playing along. Such behavior is normally frowned upon, no matter how reasonable the cause. Breaches in theatrical decorum are as unsettling to an audience as they are to a performer.

But the political and social upheaval of the last year has complicated matters. The old scripts are in the process of being rewritten. Overdue as these changes may be, they add more uncertainty to our interactions. Conflict is high, and the fear of being called out is rife. The culture, perhaps compensating for society’s uneven social progress, has been in a punitive mood. And a backdrop of gun violence has only heightened the tension.

According to Goffman, the human desire for social contact and companionship is rooted in two needs: “a need for an audience before which to try out one’s vaunted selves, and a need for teammates with whom to enter into collusive intimacies and backstage relaxation.” An essential ingredient for the smooth operation of the theater of everyday life is a “veneer of consensus” that “everyone present feels obliged to give lip service.”

That display of consensus is harder to come by. We’re returning to the public stage a splintered company. But the show must go on — and it will. For stronger than all our fears, doubts, hostilities and ambivalences is the joy of coming together for that extravaganza we call shared reality.

Pacific Opera Project’s production of Leonard Bernstein’s ‘Trouble in Tahiti’ is the city’s first major live opera show that’s not a drive-in event.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.