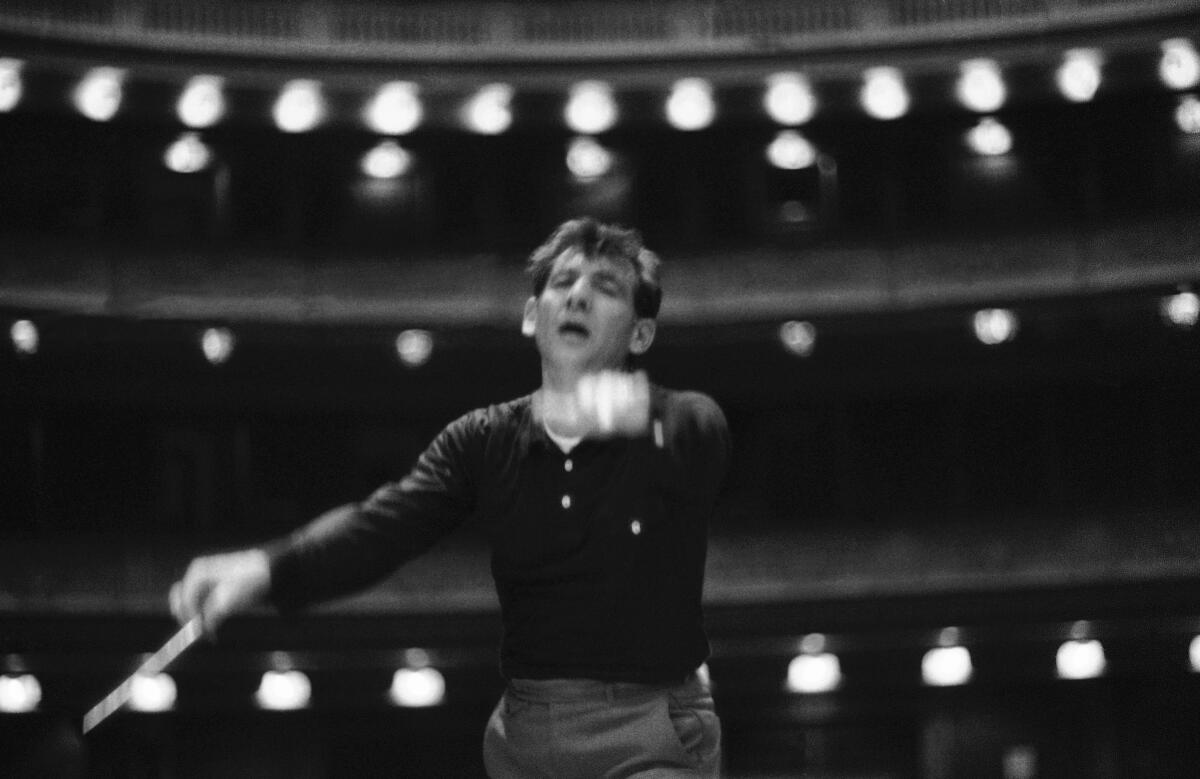

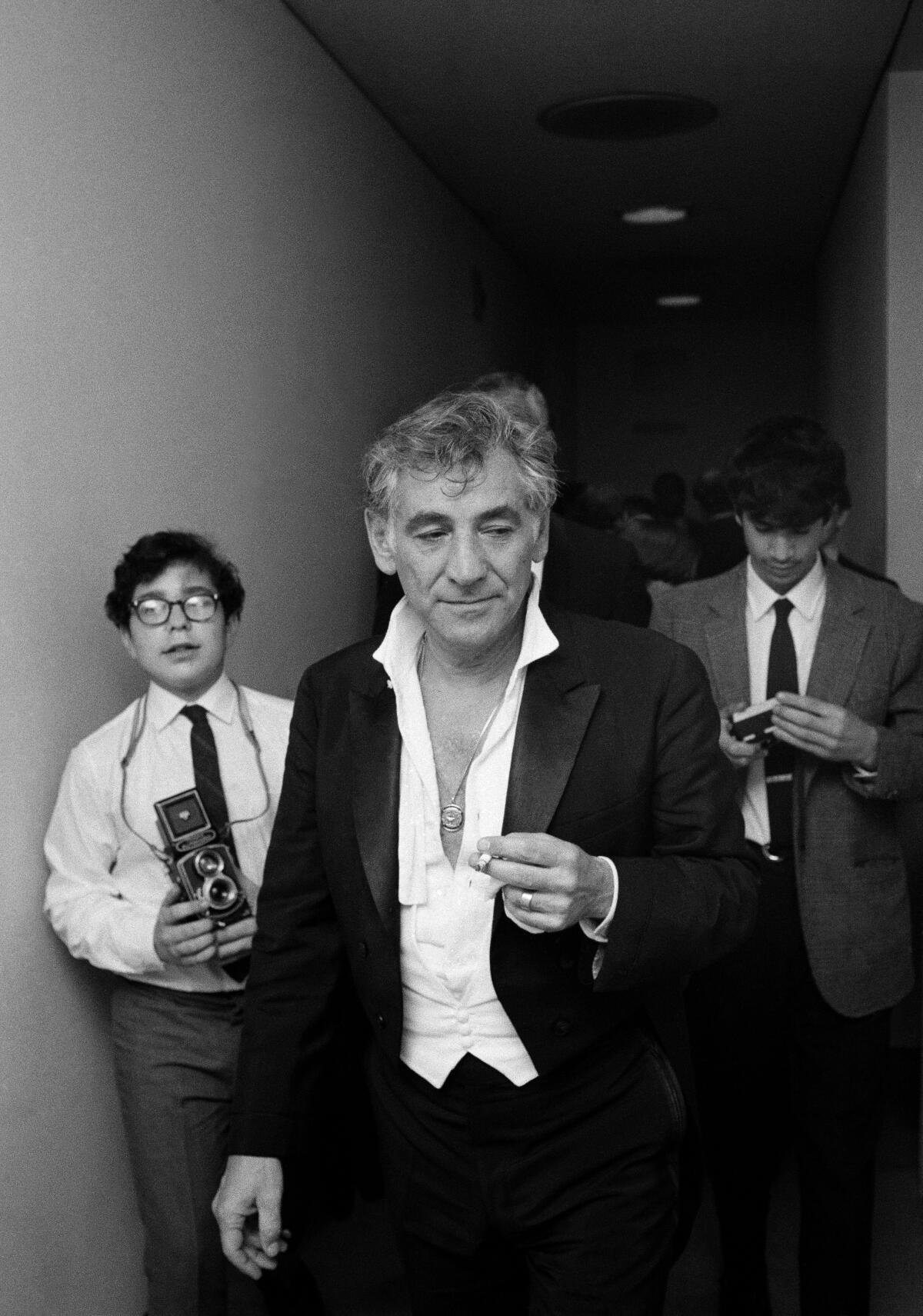

Commentary: Why it’s time to revive Leonard Bernstein’s long-dismissed, race-conscious White House musical

Bernstein had friendly and fraught relationships with U.S. presidents. But his White House musical flopped. Missed was its exploration of race and slavery that’s more timely than ever.

- Share via

In 1959, Leonard Bernstein took part in a televised celebration of Harry Truman’s 75th birthday. That same year, at the behest of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, he helped thaw the Cold War by performing with the New York Philharmonic in the Soviet Union.

Bernstein wrote and conducted a fanfare for John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, and a decade later his “Mass” opened the new John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C. President Richard Nixon did not attend, falsely convinced by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI that “Mass” had been written as an anti-Vietnam War statement meant to embarrass him. Three years later, at the inauguration for Nixon’s second term, Bernstein did, indeed, set out to embarrass the president with an anti-Vietnam War protest by performing Haydn’s “Mass in the Time of War,” at the Washington National Cathedral, attracting an audience of 20,000 while the National Symphony Orchestra was performing Tchaikovsky’s hawkish “1812 Overture” at Nixon’s request.

In 1976, as part of the U.S. Bicentennial, Bernstein and Alan Jay Lerner finished a White House musical, “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,” which includes the moving number, “Take Care of this House.” Frederica von Stade sang it at Jimmy Carter’s inauguration ceremonies, which also included the premiere of one of Bernstein’s finest songs, “To My Dear and Loving Husband,” in tribute to Rosalynn Carter.

The year before he died, Bernstein refused to accept the 1989 National Medal of Arts, letting it be known that he did not believe President George H.W. Bush was taking care of the house.

Over four decades, Bernstein had relationships — great, good, indifferent and downright bad — with nine presidents. They could not ignore him, nor he them. There was not one he did not, in some way, perturb and/or become perturbed with.

No other artist has had such a connection with the White House. If the Biden-Harris administration chooses to favor artists, as many of us hope against hope every four years that the White House will, Bernstein has much to offer as an example of just what artists might mean and how tricky that is.

The overdue creation of a Cabinet-level Secretary of Culture would give the country a lift we all crave. Here’s who I think would rise to the challenge.

A few White House-related scenes stand out. Wouldn’t you have liked to have been at Kennedy’s inaugural ball when Bernstein conducted his fanfare in Harry Belafonte’s Mexican-style shirt after a snow storm prevented him from going to his hotel to dress?

Or how about that state dinner Kennedy gave in 1962 honoring Igor Stravinsky with Bernstein in prominent attendance and Stravinsky calling Bernstein the greatest conductor of his music even if he got it all wrong? A decade later when Bernstein appeared in the Oval Office, it was as a name on Nixon’s “enemies list.”

Carter’s “People’s Inaugural” was like no other, artistically. Anyone who asked could get free tickets to nearly 200 concerts of all types of music, including an orchestral program conducted by Bernstein. Although he never got around to writing “The New Spirit,” a celebratory overture he promised for the event, Bernstein did finish a riotous political overture, “Slava!,” for Mstislav Rostropovich’s first concert at the Kennedy Center as music director of the National Symphony. The Carters, of course, attended.

Trump disparaged big cities. Here are three ways President Biden can restart the federal government’s relationship with U.S. cities.

“Slava!” contained bits from “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” as many other Bernstein pieces of the time did. He devoted four years to the musical. He wrote more music for it than for any other theater work. The show had a $900,000 sponsorship from Coca-Cola. It was billed as the musical of the decade. The show closed on Broadway after seven performances. It was the biggest artistic disaster of Bernstein’s life.

The reviews were just awful, all of them. Critics called it “simplistic,” “sophomoric” and “a Bicentennial bore.” Bernstein thought he had written his greatest show. He was right, and the simplistic, sophomoric critics were wrong. Bernstein was distraught; he nixed the release of a cast album. Everyone, including many of those whom were close to Bernstein, threw their schadenfreude-covered hands up in dismay at the mess Lenny had created.

Let me be clear, as politicians like to say, “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” is one of the great works of political theater, one that would stand with the works of Brecht and Weill were the book a bit better. And “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” could only be written by the one artist who had Bernstein’s loving and fraught White House history.

The show got attention recently when a charming all-star get-out-the-vote video was made in October of “Take Care of This House.” Writing about it in the New Yorker, Adam Gopnik noted the musical itself failed because of an awkward narrative attempt to tell a story onstage that spans generations. That’s what they all said, and maybe there is some truth in it. But I suspect the real reason “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” failed is because it dared to tell a story onstage that spans generations that a lot of people didn’t want to hear. And because a sophisticated score quite simply went over their collective mainstream Broadway heads.

“We are trying to tell the story of the little white lie,” Bernstein said of the show’s scenes of White House dysfunction in the years from George Washington to Theodore Roosevelt, “by which I mean the big Black lie.” The aspirations of presidents are contrasted with the lives of their Black servants and the racial situation of the country in general.

Trump separated families. But Obama broke his promise to pass immigration reform. Biden’s opening executive actions are promising, but will he disappoint too?

The witticisms can be wickedly sly. Characters are carefully confounding caricatures, be they Black or white, and potentially problematic if that satirical wit is not given full context. The same pairs of white singers and Black singers impersonate the presidential couples and their servants. To make matters all the more complicated, this was presented as a musical show within another musical show, with cast members engaging in racial arguments.

So what if that’s confusing? That’s the point. It is a hell of a lot easier to reconstruct a messy narrative than it is a country.

I question just how much of a mess Lerner’s book, for all its clumsiness, is. These are the kinds of racial conversations we are now having everywhere. We’ve lately seen the White House get unprecedented attention — not just politically but also the very house itself. Had Time magazine run a controversial cover of a trashed White House like this year’s inaugural one in 1976, maybe “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” would have seemed different then.

Bernstein became phobic about the show and refused to work on it once it closed. He wouldn’t publish the score. But after his death, a concert version called “A White House Cantata” was made. Kent Nagano recorded it with the London Symphony and an outstanding cast in 1998. Neither the recording nor the cantata developed legs. It was all but brushed under the rug during the centennial overload.

On the first day of 2018, a dozen cities in Germany, from Augsburg to Wiesbaden, celebrated a new year with concerts that included music by Leonard Bernstein.

But the fact is, it contains one magnificent and provocative song after another. As in “Mass,” Bernstein changes idioms by the minute and rhythms, to Broadway’s dismay, by the bar line.

There is outrage galore. Among Thomas Jefferson’s luncheon delicacies is his favorite dessert, Brown Betty, a wicked reference to the presidential fancy for slave women. Mrs. Monroe exposes her husband’s and the Founding Fathers’ systemic racism in what has to be Broadway’s most bittersweet lullaby.

There is sure to be controversy in trying to bring back “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue,” with songs such as the engaging calypso Black anthem “Bright and Black” written by two white men. “The Money-Lovin’ Minstrel Show” that parodies the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts buying influence is startling to say the least. The lyrics cannot stand without Bernstein’s score, which has instances of incredible complexity by Broadway standards along with great tunes by any standards.

Mainly, though, Bernstein works in extremes. Sure, there is sentimentality. “Take Care of This House” is sentimental (though try to resist it). The finale, a hymn, “To Make Us Proud” is sentimental in the extreme. `But after all that has gone before, to hear, in full-bore Bernstein grandeur, with consonant harmonies sugared and spiced with tingles of dissonance, “To burn with pride/And not with shame/Each time I hear my country’s name,” resounds in ways an American has no right to resist.

What would Bernstein have thought of “Hamilton”? He probably would have loved it. And envied it. He had been there first (well, Gershwin was way ahead of them all with his 1932 presidential hit show, “Of Thee I Sing”). He was more progressive. But what he didn’t have presumably was the production he needed or the chance to develop the show off Broadway. He knew deep down that what killed “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” was his own commercial compromise, Coke’s money and the establishment expectations of his own and Lerner’s celebrity.

To revive “1600 Pennsylvania Avenue” properly requires a theatrical savvy it has never had. The few attempts to mount it have led to nothing. It belongs more in an innovative opera house than a commercial theater (Nagano’s recording uses classically trained singers to engaging effect). The Cantata version works in concert and is more than suitable for semistaging (again with imagination).

What the White House, the real one and the Bernstein’s musical one, necessitates is artistic bravery. In 1970, two years before working on the show, Bernstein said this to students at Tanglewood: “It is the artists of this world, the feelers and thinkers, who ultimately save us, who can articulate, educate, defy, insist, sing and shout the big dreams.

“Only the artists can turn the ‘not yet’ into reality.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.