Nipsey Hussle helped to save this L.A. skating rink. Now its future is uncertain

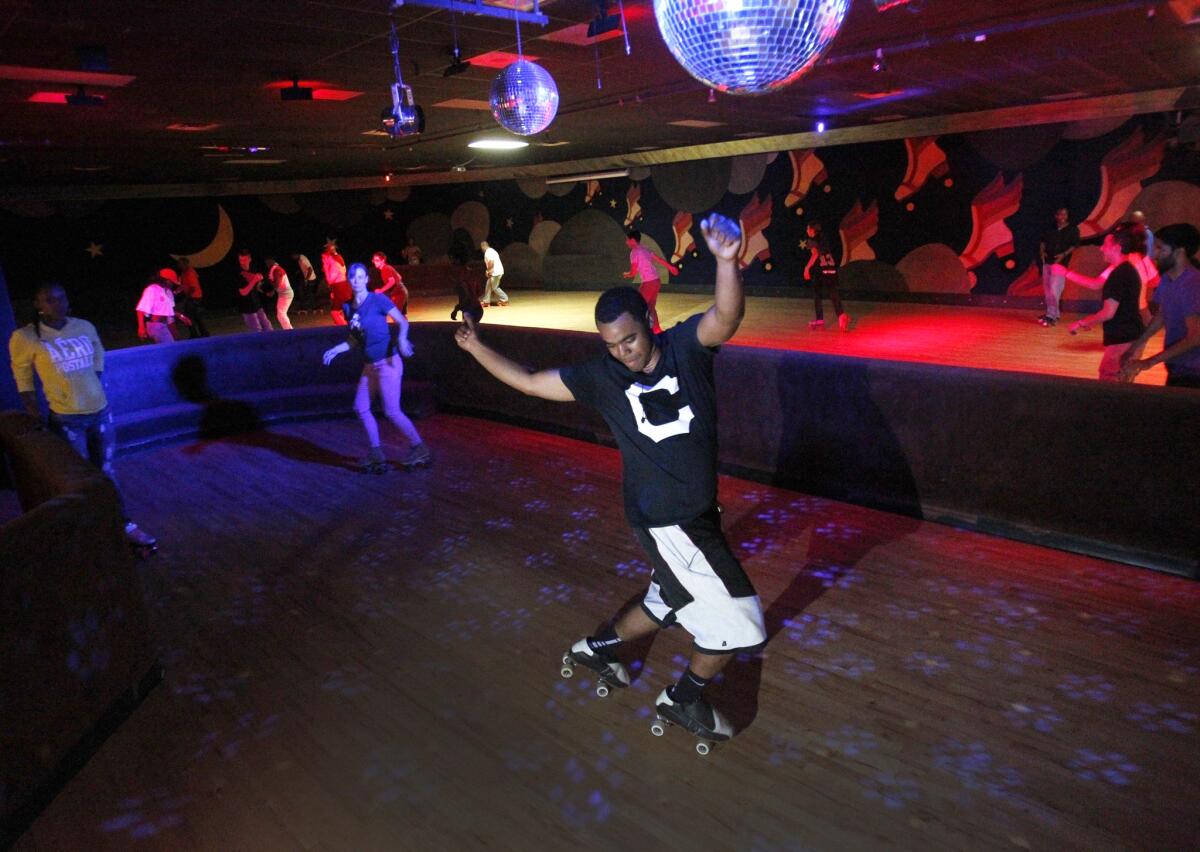

Skaters traverse the floor of World on Wheels in 2017, after the rink had reopened after a four-year closure.

- Share via

When World on Wheels reopened in 2017 after a four-year closure, a line of eager skaters wrapped around the building, custom skates and rollerblades clenched in their arms.

The beloved Mid-City skating rink was more than just a place to lace up and glide. It was a cultural institution — part of Los Angeles’ early hip-hop scene and a safe haven for youths who came from rival neighborhoods in South Los Angeles. Skaters looked to this rink variously as date destination, fitness facility, daycare center, therapist office or family room. Thanks to an enthusiastic entrepreneur who won the support of rapper, community activist and local hero Nipsey Hussle, the rink received a much-needed face-lift that drew fans back to the hardwood floor.

“They were our unicorn story,” said Dyana Winkler, the screenwriter and co-director who documented the demise of American skating rinks as well as the unlikely return of World on Wheels in the HBO film “United Skates.” “The fact that it closed and was so painful to the community but then was able to reopen was the happy ending of our film.”

Although the unicorn didn’t lose its magic, it did lose a significant amount of revenue, and now World on Wheels has closed again. This time, maybe for good.

It wouldn’t be incorrect to label World on Wheels another casualty of COVID-19. The state’s stay-at-home regulations have forced entertainment venues such as the skating rink to shutter to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. With expenses like rent still accumulating but revenue going to zero, some businesses have no choice but to quit.

- Share via

After seeing roller skaters on her social media feeds, arts reporter Makeda Easter decided she had to try it out for herself.

But the death of World on Wheels is complicated. It comes with allegations of racism, insinuations of a plot by police to thwart Hussle and a souring relationship between landlord and tenant. In the end, it is the community of skaters who have lost.

“It’s a heartbreak all over again,” said Marie Brown, 34, noting that the rink is where her parents met and where she got one of her first jobs in college. “It’s unfortunate to see such a beautiful business with such rich history just go down the drain.”

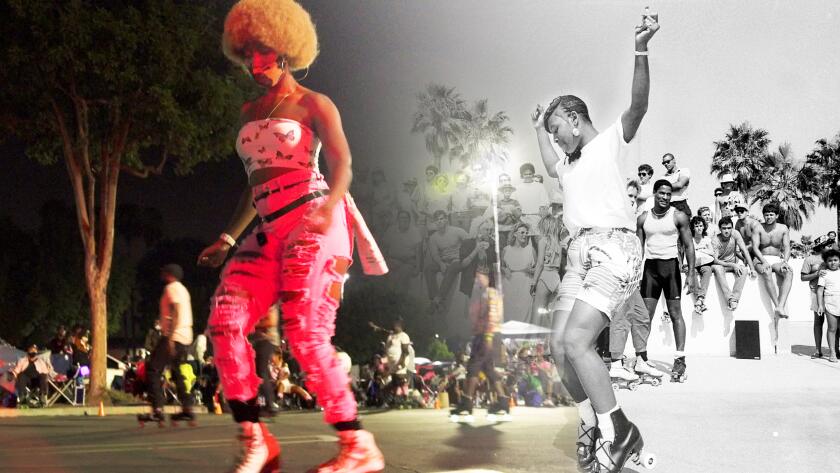

World on Wheels was born in 1981 at the height of the roller skating craze. Located at the corner of Venice and San Vicente boulevards, the rink was known for its “7 to 7” lock-in parties, where parents could drop off their kids for 12 hours of roller skating and safe socializing. Rising musicians worked with the rink’s DJs to test new releases. And when gang violence peaked in South L.A., World on Wheels became neutral territory to which children could escape. (In “United Skates,” one man said the rink felt safer than church.)

In the ’80s and ’90s in L.A., if you were a teenager, World on Wheels was the hottest club in town.

Financial woes closed World on Wheels in 2013. Then Tommy Karas and a business partner reopened the rink in 2017 with a modernized look. Hussle, who frequented the place in his youth, provided financial backing for the renovation. A community of roller skaters and World on Wheels loyalists rejoiced.

The resurrection was celebrated in The Times and L.A. Weekly. But behind the scenes, Karas said, his battle was just beginning with the building’s landlord, Young Management Co., run by father and son James and Courtland Young.

In 2018, Young Management Co. attempted to evict Karas, he said, for not paying a property tax fee that wasn’t included in his original lease. (Young Management did not respond to requests for comment.) Karas said he in turn sued the Youngs. The legal battle went on for more than two years, Karas said.

“It was doomed from the beginning, honestly,” Karas said of World on Wheels’ prospects for survival.

In a deposition video obtained by The Times, Courtland Young said that after news outlets published stories discussing Hussle’s involvement, an officer from the nearby Wilshire Community Police Station asked to meet. Hussle, born Ermias Asghedom, garnered respect from some community leaders for his community activism and philanthropy, but he touted his gang affiliation in his rap lyrics.

According to Courtland Young’s deposition, the officer told him: “You should really consider protecting your best interest or asset by maybe amending the lease or doing something above and beyond because … this guy is a known gang banger and has a long rap sheet.” Courtland Young took the advice but said Karas didn’t sign the leasing amendment.

Young didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

LAPD Capt. Shannon Paulson, the commanding officer for the Wilshire area since February, said the department held meetings with Karas and Young, jointly and separately, to address criminal activity patterns that emerged when the rink reopened in 2017.

“We initiate meetings of this kind with anybody and everybody, and there’s nothing secret about it,” she said.

But World on Wheels’ Karas, who is white, said the rink’s predominantly Black clientele was not the desired demographic of other businesses in the Youngs’ shopping center, which included a grocery store, furniture shop and fast-food restaurants. Courtland Young did not respond to requests for comment on the subject.

Karas said Hussle, whom he considered a friend, pushed him to continue “fighting the good fight.” But in 2019, Hussle was fatally shot outside his South L.A. clothing store. And then in 2020, World on Wheels, like so many other businesses, got hit by the pandemic.

COVID-19 restrictions forced the rink to close in March. It reopened in June — but had to close again after just one day. Karas said he is now 10 months behind on rent, which he said is about $35,000 a month. He has nearly $200,000 in additional debt from legal fees.

Some fans lamented that Hussle never would have allowed World on Wheels to close, but Karas said he has no choice, and the loss has been emotionally and financially devastating for him.

“I put every dollar I had into that place and more,” he said. After working in the nightlife industry for 15 years, he took over the rink with hopes of turning it into a community venue centered on children.

People might have lost their favorite rink, he said. “I lost my livelihood.”

Los Angeles Rep. Karen Bass, congresswoman for the rink’s district and also a former World on Wheels patron, said she’s sad to see it go. She said her office did all it could “ethically and legally” to support Karas.

“It’s a space that I loved,” she said. “I’d love to see it stay open.”

On Instagram many people shared memories of World on Wheels, while others commented “not another one” and “#saveourrinks,” noting the closure of skating sites around the country, even before the pandemic. (A month before the World on Wheels news hit, Skateland Northridge in the San Fernando Valley announced it was closing.)

Phelicia Wright, whose love of the rink dates back to the early 1980s, — said the community lost one of the few places for Black youths to entertain and express themselves.

Some people turned to sourdough. Others became plant parents. My pandemic hobby of choice? Roller skating.

Some hold out hope that it will return.

A few optimistic employees sent requests for donations to former customers on social media, but Karas said the effort quickly stopped after many customers replied that they too were struggling financially due to the pandemic.

Karas plans to file for bankruptcy, but in the meantime he’s focusing on where he can continue the World on Wheels legacy.

“Inglewood or Compton, here we come,” Karas said, sounding the most optimistic he’d been in weeks.

For now, the marquee is blank on the tan building that used to house World on Wheels. The name has been removed, and a community of skaters is grieving.

“It is a major loss,” Brown said as she fought back tears. “It’s like losing a piece of who I am.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.