- Share via

At midnight tonight, according to a deep vein of folklore in Mexico and parts of Latin America, the spirits of the dead come nearest to those of us who still bear the burden of living.

It is the eve of Nov. 2, the Day of the Dead. The living gather around offerings: candles, flowers, especially brilliant marigolds, and images of the departed. The souls are drawn to the merriment. Their memory, in effect, is revived.

Martha Jimenez of East Los Angeles usually loves putting up altars for this tradition. But she’s been dreading this day for weeks.

A florist, 66, she is usually extra busy this time of year with orders at Alisol Flowers, her family’s modest discount gift business on East Cesar E. Chavez Avenue. She has been making Day of the Dead altars all her life, since her childhood in Mexico, and is known for her altars in her East L.A. community.

This year is different. This year, many altars — too many — will be for victims of COVID-19.

“The dead? There are so many,” Jimenez said, gesturing to the neighborhood outside. “And so many from COVID.”

The pandemic has quieted one of the country’s signature holidays — Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, when Mexicans honor deceased loved ones in often-boisterous fashion.

One of those victims is hers. Pedro Robles Bravo, her brother, died of the virus at age 69 in Mexico. Jimenez watched the funeral online. To her, the experience wasn’t a full goodbye. As Day of the Dead approached, Jimenez was hesitant.

“If we put up the altar, it will almost be like accepting he is really gone,” she said inside her shop last week, her eyes welling with emotion. “I have to do it at some point.”

This is the saddest Day of the Dead in memory in Los Angeles.

All over the region, in people’s homes and in plazas and parks, altars have been prepared for tonight’s celebration. Many Angelenos like Jimenez find themselves observing a Día de los Muertos in 2020 like none other in their lives: apart, and with so many dead.

More than 3,400 Latinos in L.A. County, many of them essential workers or their family members, have been lost to the virus — by far the largest share of the more than 7,000 COVID-19 deaths tracked in the county through the end of October.

Indigenous tradition

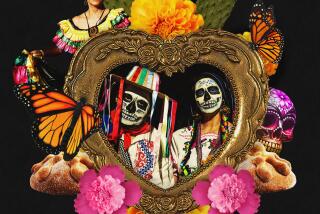

Day of the Dead in the 21st century is experienced as a phenomenon halfway between the intimacy of a sacred ritual and the vulgarity common in U.S. consumer culture.

The tradition, particularly in indigenous communities, is still practiced with utmost reverence to its roots, with careful observance of the elements required for an ofrenda: a pathway set by marigold or cempasuchil petals, and photographs of the departed.

The co-option of Day of the Dead by market forces, as purists say, has also given us the rise of so-called Sexy Catrina costumes around Halloween, a nod to the early 20th century engravings by lithographer Jose Guadalupe Posada, images embedded so deeply into the broader culture that the style represented by the Posada works has become visually ubiquitous.

There’s also a Day of the Dead Barbie doll, a hot seller for Mattel.

Since the tradition crept into the mainstream in recent decades, the Día de los Muertos of Nov. 1 and 2 has become a full-blown community spectacle in Southern California.

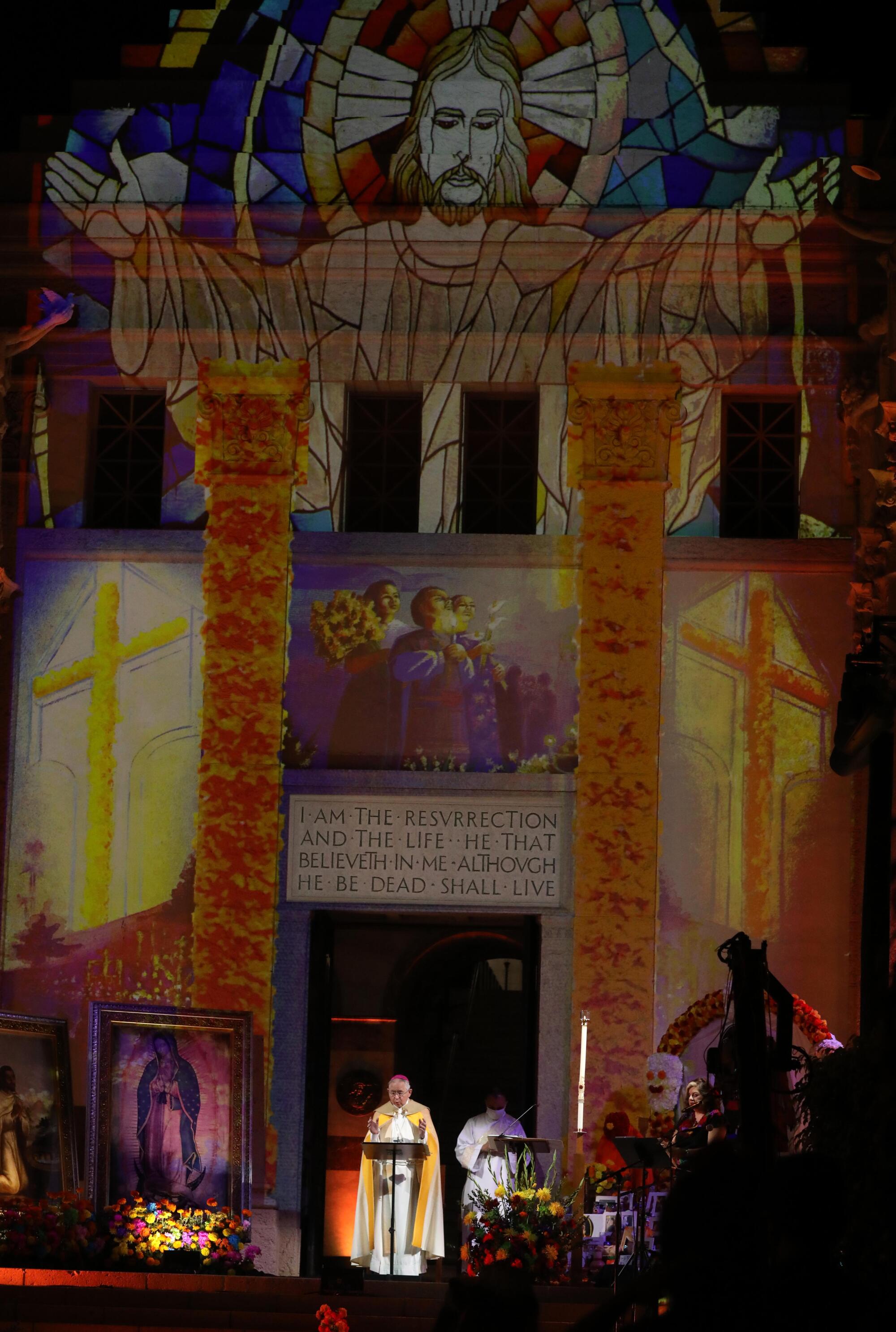

But because of the pandemic, the seasonal fairs, festivals, and public walking displays of Day of the Dead ofrendas have been pared back significantly or gone entirely virtual this year to keep people safe. The annual music and altar event at Hollywood Forever cemetery, one of the buzziest nights in town, is virtual today starting at noon, and will feature performances by members of Los Lobos. (Streaming is available here.)

At Pacoima City Hall, the annual ofrenda display has turned into a drive-through community altar for victims of COVID-19. Residents sent images of people lost to the virus to the office of City Councilwoman Monica Rodriguez.

“My community is among those on the front lines that have been hardest hit,” Rodriguez said in an interview. “It was important to continue with this tradition, particularly since the community has been so demoralized because of the pandemic.”

The most beloved celebration in Los Angeles takes place every year at Self Help Graphics & Art in Boyle Heights. Betty Avila, executive director of Self Help, said there was no doubt that the venerated arts organization would hold an event — in some form — this year. The customary art exhibit is now virtual, and the group is leading a drive-by caravan today for Día de los Muertos at Grand Park.

“We’ve had to shift in every possible to really translate that experience,” Avila said. “It’s a year where there’s been so much loss. A loss of life, a loss of economic stability, health, and this racial justice movement sparked by the murders of multiple Black people.”

The impact of the pandemic on all aspects of the lives of people of color is enormous, Avila said.

“We’re still so deep in it, that we’ll continue to be processing this for next Día de Muertos,” she said. “We’re still going to be unpacking this loss.”

Toll on essential workers

Everything about the pandemic has been a nightmare for working-class Latinos and Black Americans, who fill the ranks of essential workers at farms, hospitals, kitchens, schools and at public utilities such as transportation, trash and recycling networks as well as the post office.

At the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 770 in Koreatown, union members have set up a large altar for fellow essential workers who have succumbed to the virus. One of those is Cruz Garrido Ocampo, who worked at a poultry processing plant in Vernon, said his husband, Pedro Garrido.

Cruz died in August, while in his hometown in the state of Guerrero, Mexico. He was 57. His partner Pedro stood outside the union’s headquarters, recalling the man he met 30 years ago on a cruise ship. The pair were active with L.A. Pride and lived together in Boyle Heights. They married in 2013.

“Thirty years, it’s a lifetime,” Pedro Garrido said, tearing up.

Pedro now has an altar for Cruz in their home, with a photograph of him, a candle alight “day and night,” and carnations, which were his departed’s favorite flowers. “It’s my first time participating in an altar. This is how I can honor him,” he said.

Artists and storytellers often use Day of the Dead tradition to highlight the lives of those who have died unjustly. In that spirit, visual artist Consuelo G. Flores this year installed an ofrenda that honors the COVID-19 dead at Self-Help.

“Whenever there are groups of people who have been murdered, or have died for whatever reason, I tend to want to call attention to those deaths and to honor the people who have died,” Flores said. “So I’ve done altars for the women of Juarez, for Ayotzinapa, for victims of the Grim Sleeper, for the Pulse shooting, and now the pandemic.”

The artist set out tropical plants in moss in the ground, and placed arrays of paper flowers attached to wooden branches, hanging upside down from wires. And on those, she placed small reproductions of photos of Black or Latino people from across the country who have died in the pandemic.

Flores said this year’s Día de los Muertos will be more significant than ever, and the way it has altered all our lives, even in times of mourning.

“Where there has not been that opportunity to attend a funeral, to have an end-of-life ceremony,” she said, “the altar for Day of the Dead becomes the sort of ritual that a lot of people are holding onto and really participating in, so they can have that closure.”

Saying farewell

Martha Jimenez’s brother called her in late September to share the news: He had the coronavirus. A prominent doctor and dedicated medical training teacher in Guadalajara, Pedro Robles told his florist sister he had likely caught the virus from one of his students. She asked if he had seen a doctor and he said, “I am the doctor.”

Robles went to a hospital and never returned home. Jimenez’s eyes welled slightly with tears, and she seemed to forcefully contain her emotions. “You look at him and say, ‘It wasn’t his time.’ ”

Jimenez, along with her husband, Alfredo Jimenez, and daughter Patty Moreno, has been selling flowers and discount gifts from this tiny East L.A. shop for nearly thirty years. The pandemic shutdowns forced her to close one of her other stores. Jimenez stood in the dimness of Alisol Flowers, describing the COVID-related stories she’s heard from regular customers. One woman told Jimenez she lost seven relatives to the virus. “Another customer told me she’s lost three people, one one week, one the next, and one the next,” the florist said.

Late in the week, Jimenez finally put the altar together, just outside her shop. She decorated it with a “medical theme,” in honor of her doctor brother in Guadalajara.

She said she wants to remind everyone who sees the altar that the pandemic is real, and deadly.

“When I see someone who isn’t respecting others, who isn’t in a mask, it bothers, it really does,” Jimenez said. She tells unmasked neighbors about her brother Pedro.

“He left us because it is your fault, those of you who don’t take care of yourselves. Do you know how many people it’s killed?” she said she asks others. “And it is taking people who are in good health, like my brother.”

Jimenez stops again to ponder the toll the pandemic has taken on her neighbors, her family, her community in East Los Angeles, the cultural heart of Mexican Los Angeles. Her home.

“It is so sad,” the florist said, her eyes glassing over with light again, overwhelmed. “And it is so serious.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.