Why George Lewis’ revolutionary ‘Shadowgraph, 5’ can last 3 minutes or 4 hours

- Share via

On his new-music blog, Tim Rutherford-Johnson posted a timely, thoughtful Black Lives Matter-related playlist in June that included George Lewis’ “Shadowgraph, 5.” The following week a performance of “Shadowgraph, 5” turned up on a virtual marathon concert held by Nief-Norf, the Knoxville, Tenn., new music group that holds an annual summer festival (this year online). Also that week, I heard Lewis described on the BBC as “a towering figure in the avant-garde.”

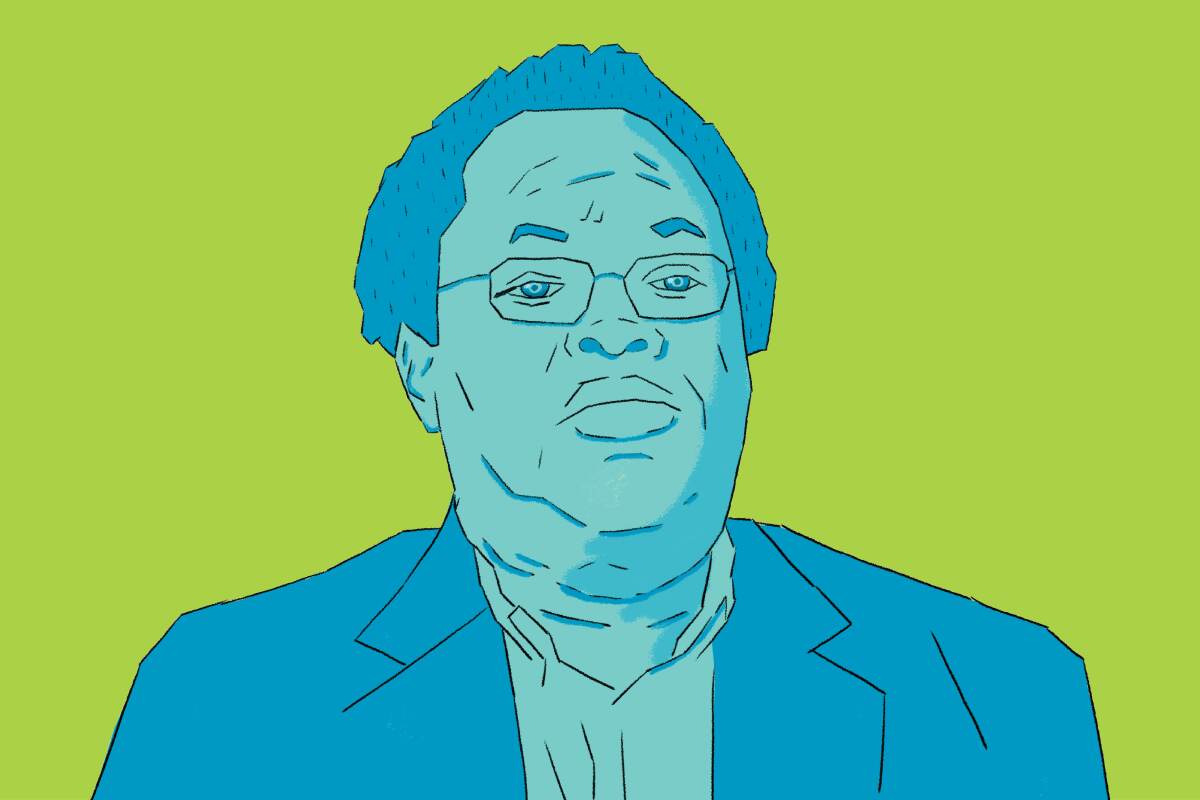

There can be no question that this protean composer, performer, scholar, professor, administrator and genial gadfly exerts a profound influence on how music is made, thought about and might be listened to in our times. But Lewis, 68, tends to keep a somewhat low profile. And while “Shadowgraph, 5” has had an undoubted significance in the history of American music and gets notable performances from time to time, it too evades all but the most sensitive new-music radar.

For the record:

11:06 a.m. Aug. 20, 2020An earlier version of this article said Nief-Norf is based in Nashville. It is in Knoxville, Tenn.

Nothing about “Shadowgraph, 5” indeed shouts “iconic.” To begin with, it is difficult to say exactly what this piece is. There isn’t much to go on. It can be for any number of players. It can last any agreed upon amount of time. When the International Contemporary Ensemble paired “Shadowgraph, 5” with Schubert’s octet for winds and strings in Chicago in 2013, the octet version lasted three minutes, whereas three years ago “Shadowgraph, 5” served as the basis for a four-hour marathon staged by the NOW Society (short for New Orchestra Workshop) of Vancouver.

So improvisational is “Shadowgraph, 5,” three commercial recordings made over a span of four decades offer no real aural clues to the fact that this is the same piece. Players act in the moment, embracing, to use one of Lewis’ favorite terms, mobility. Go ahead and Google “Shadowgraph, 5.” You will find commercial recordings, live performances and the occasional link to a not particularly helpful review. We, as listeners, are pretty much on our own.

And yet, from the first moments of the first “Shadowgraph, 5” recording, which Lewis made in 1977 with a remarkable sextet that featured him on trombone, tuba sousaphone and sound-tube (whatever that is), the music can grip you and not let go. A pop (the sound-tube?) calls you to attention. An alluring flute solo (Douglas Ewart) seduces. Next, jump-starting plucks on the cello (Abdul Wadud) underpin jump-for-joy piano glissando (Muhal Richard Abrams) followed by siren calls on a viola (Leroy Jenkins) and Lewis’ trombone burping and cauldron-hot bubbling. That is just the beginning.

What I hear in this sextet is the reproduction through sound of the mental processes through which powerful ideas are formulated in discourse, the adrenaline rush of a communal brainstorm that takes over your senses and wildly elevates your mood. Listening to group improvisation, no matter how exalted, is a form of illuminating eavesdropping. Here we are invited into a thought process, the adrenaline flow stimulating our own. This is what community can mean and do. The implications for society, demonstrated not demanded, are immense in Lewis’ music.

Ecstasy and excess, rhythm and repetition, gender and ethnicity. Lyricism, protest, healing. Critic Mark Swed’s series on the ideas embedded in every note.

“Shadowgraph, 5” is the fifth of a series of pieces by Lewis for the idea of a “creative orchestra” that came out the Assn. for the Advancement of Creative Music. Founded in Chicago in 1965 by Abrams and other Black musicians as a collective of composer-performers, the AACM was, and still is, a communal basis for exploring and expressing the African American experience. Jazz was a common background, but Lewis — who wrote the definitive history of AACM, “A Power Stronger Than Itself” — says that he never once heard jazz, per se, discussed at the AACM. The concern was with using all means available for musicians of very different personalities to create something bigger than any one of them and to reveal the power of what Lewis has dubbed the “Africological” basis and necessities of modern music.

Lewis was 25 when he wrote and recorded “Shadowgraph, 5” in 1977. It is the first flowering of a second-generation AACM trombonist who joined the collective as a brilliant teenage musician with a limitless intellectual and technological curiosity. Lewis went on to major in philosophy at Yale, giving him both a conceptual and broad musical framework with which to produce a dizzying array of idea-filled work that is expressly thought-through and yet spontaneous.

That flowering led for the next 15 years to touring and recording with an array of performers from experimental American (jazz and otherwise) and European (jazz and otherwise) music, working with all kinds of electronics, appearing on on more than 100 recordings and, for two years, serving as the director of the Kitchen when it was the premier site for new performance in New York’s SoHo district. In 1992 Lewis became a professor at UC San Diego (where he happened to be a colleague of Pauline Oliveros). Since 2004, he has been a leading light in the music department at Columbia University. He’s picked up all the meaningful awards: MacArthur, Herb Albert, Guggenheim, Doris Duke.

Lewis has produced a number of completely written out pieces, including his compelling “Afterward,” an ecstatic opera of ideas — ideas about the birth of the AACM — that was staged at the 2017 Ojai Music Festival. He has created intermedia installations. He has explored artificial intelligence. A tech geek, he has even written a piano concerto for a computer-controlled, AI-improvising soloist that “listens” to and reacts to a live orchestra. But whatever Lewis does, the spontaneity of the moment is always of the essence.

Through it all, Lewis has insisted on the crucial African American contribution to Western music — in particular improvisation in all its ramifications — and he has been critical of those who ignore or deny it. In an influential musicological essay, Lewis positioned the influences of Charlie Parker and John Cage on modern music, noting the difference between the revolutionary shock of Bird’s bebop and what he considers the more aestheticized aspect of Cage’s uses of indeterminacy. It is a nice touch that the newest recording of Lewis’ music, his quirkily imaginative “String Quartet, 1.5: Experiments in Living,” written for the Chicago-based Spektral Quartet, will be released Aug. 28, the day before what would have been Parker’s 100th birthday.

Even so, it’s always been a Bird Cage world for Lewis, who, in fact, has a close relationship with the last surviving member of Cage’s New York School, Christian Wolff, with whom he performs and about whom he writes with uncommon perception. Indeed, what ultimately makes Lewis such a provocatively persuasive academic, arresting player and thought- and emotion-provoking composer is how he adds the concept and acknowledgement of race to just about everything he does without ever separating himself from the larger world.

That “Shadowgraph, 5” began a lifelong exploration of the implications of interaction is, perhaps, nowhere more moving than in his 2011 recording, “The Unusual Turmoil.” This is a series of, of all things, trombone and koto duets. Unusual turmoil turns out to be unusual musical love letters between Lewis and his wife, the Japanese composer and koto virtuoso Miya Masaoka. In these extraordinary intricate and intimate duets, a boisterous trombone is shown to possess a seemingly impossibly delicate soul; a formal koto tradition is shown to live in the moment. Mobility is shown to be a form of love.

Starting points

You can spend the rest of pandemic lockdown, no matter how long that turns out to be, seeking out and listening to George Lewis’ recordings here, there and everywhere.

“Shadowgraph, 5,” the first recording, which includes a series of other early Lewis pieces, is now a classic. It’s available on CD and on various streaming sites.

Other perspectives are offered in “The Shadowgraph Series” from 2000, found on YouTube, and “The Will to Adorn” from New Focus Recordings, which includes a more recent performance by ICE.

Two important surveys of Lewis compositions, “Assemblage” and “Changing With the Times,” can be found on the excellently sourced New World label. A superb video of an “Afterword” production has been uploaded to Vimeo.

Elsewhere, Lewis is at his most impressive playing with the likes of Steve Lacy and many of the AACM musicians, such as Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell and Anthony Braxton. A wonderful introduction to Lewis and how he listens can be found in his recent appearance as DJ on the Specktral Quartet’s online Floating Lounge.

With live concerts largely on hold, critic Mark Swed is suggesting a different piece of recorded music by a different composer every Wednesday. You can find the series archive at latimes.com/howtolisten. Please support Mark’s work with a digital subscription.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.