- Share via

Scattered in storefronts and light industrial buildings around Los Angeles are gallery exhibitions trapped in suspended animation. The fully installed shows had opened — or were about to open — when California’s governor issued a stay-at-home order on March 19 and now sit in the dark, under lock and key until the COVID-19 pandemic abates.

At L.A. Louver in Venice, two exhibitions in limbo feature painstakingly detailed works by L.A. painter Tom Wudl, inspired by a key Buddhist text, and more than a dozen never-before-exhibited paintings by the late Don Suggs, works that turn broad swathes of color into impish beings.

Across town, at Charlie James Gallery in Chinatown, realist paintings by Long Beach-based artist Narsiso Martinez portray farm laborers on grocery store produce boxes — works that come at a moment in which the pandemic has thrown the risks of farm work into stark relief.

To the south, in the Arts District, at Vielmetter Los Angeles, hang shows by abstract painter Elizabeth Neel and L.A.-based photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Sepuya’s sensuous images explore the male nude and the queer black body, while toying with the nature of photography, the camera itself and the role of the artist (his work is usually shot in reflection).

“Our schedule is completely up in the air,” gallery founder Susanne Vielmetter says. “I have two beautiful shows that have been seen by nobody.”

The Neel and Sepuya shows were supposed to open on March 14, but Vielmetter shut down the space the day before, just as other arts organizations around the city were also closing.

Like every other gallerist, she is now trying to figure out how these works might be seen — if at all.

One thing is certain: The art world as we know it will not be the same one that emerges from the other side of this pandemic. What will change?

Surveying the uncertainty

The Times reached out to several dozen Los Angeles galleries, small and large, with an informal and anonymous survey about the challenges of the current stay-at-home phase of the pandemic and what they will face after their doors reopen. Almost three dozen galleries — 35 in total — responded.

No one is coming out of this unscathed.

— Eva Chimento, founder of Chimento Contemporary

Some who took the survey declined to be interviewed for this story; others who were interviewed preferred not to participate in the survey. In combination with interviews with gallerists around the city, the survey helps paint a picture of what the landscape may look like when California emerges from quarantine.

One troubling forecast: A quarter of the respondents, nine of 35, said they are facing the permanent closure of their spaces in 2020 if the situation doesn’t improve quickly. An additional five galleries, or 14%, say closure is a possibility. The numbers are in keeping with a far more comprehensive study issued by the Comité Professionnel des Galeries d’Art, a French trade organization, which estimates that one-third of French galleries could shut down before the end of the year because of the steep losses in revenue.

In addition to potential closures, The Times survey reveals a much slimmer gallery scene will likely emerge — one that eschews most airplane travel to international art fairs in favor of staying local.

It’s a huge shift. In early March, just before stay-at-home orders started to take effect in the U.S., gallerists, artists and collectors from Los Angeles were jetting off to the art fairs in New York City and making plans to attend other art fairs around the world.

The length of the lockdown, the severity of the virus, the development (or not) of a vaccine and the rebound (or not) of the global economy and, with it, airplane travel, will all determine how and when galleries will be able to bounce back.

Some spaces are liable to shrink considerably; many others will disappear — and with them an important source of professional development and income for many artists as well as a whole host of other industry jobs, including crating and shipping, storage, installation, conservation, photography and framing. It’s a gutting that could lead to further inequity in the current market, in which small and midrange spaces are squeezed out by global mega-galleries, such as Gagosian and Hauser & Wirth.

“No one knows how this will go down,” says Jeff Poe, co-founder of Blum & Poe, based in Culver City with branches in New York and Tokyo (two cities also under lockdown). “It could go back to the Los Angeles that once was — in the ’90s, when things were quieter.” It was in those recession-era days — 1994, to be exact — when he and partner Tim Blum established their gallery.

Peter Sellars — opera director, spiritual thinker, optimist — reflects on changes triggered by coronavirus. Amid tragedy, what new life might come forth?

“No one is coming out of this unscathed,” says Eva Chimento, founder of Chimento Contemporary, an emerging space in West Adams that had just extended a show by Dutch painter Michael Tedja when the shutdown arrived. “That’s the sad truth.”

Virus hits close

It is impossible to know the path the virus may take through communities of artists, gallerists and collectors. Of the gallerists polled, 29 of the 35 have a colleague or close friend or family member who has been affected by a presumed case of COVID-19; five report they know someone who has died from complications related to the disease.

And it’s impossible to know how the pandemic will affect art dealing. Galleries are private businesses through which art is sold, generally via a chimeric formula that involves talent and buzz marinated in artspeak. Dealers are generally loathe to tell a story that isn’t rosy, especially when it comes to their own finances. Moreover, no two galleries are created equal. Some are locally focused one-man-band shops; others are behemoths with branches in global capitals. The story of a single gallery, or even a handful of galleries, is hardly a stand-in for all.

Consider the diverse lot of the respondents to The Times survey: Nearly half of the 35 respondents are small spaces of three employees or fewer, more than a third are middle-of-the-road galleries of between four and 12 staffers and 14% have staffs of more than a dozen, some of them the L.A. outposts of international galleries.

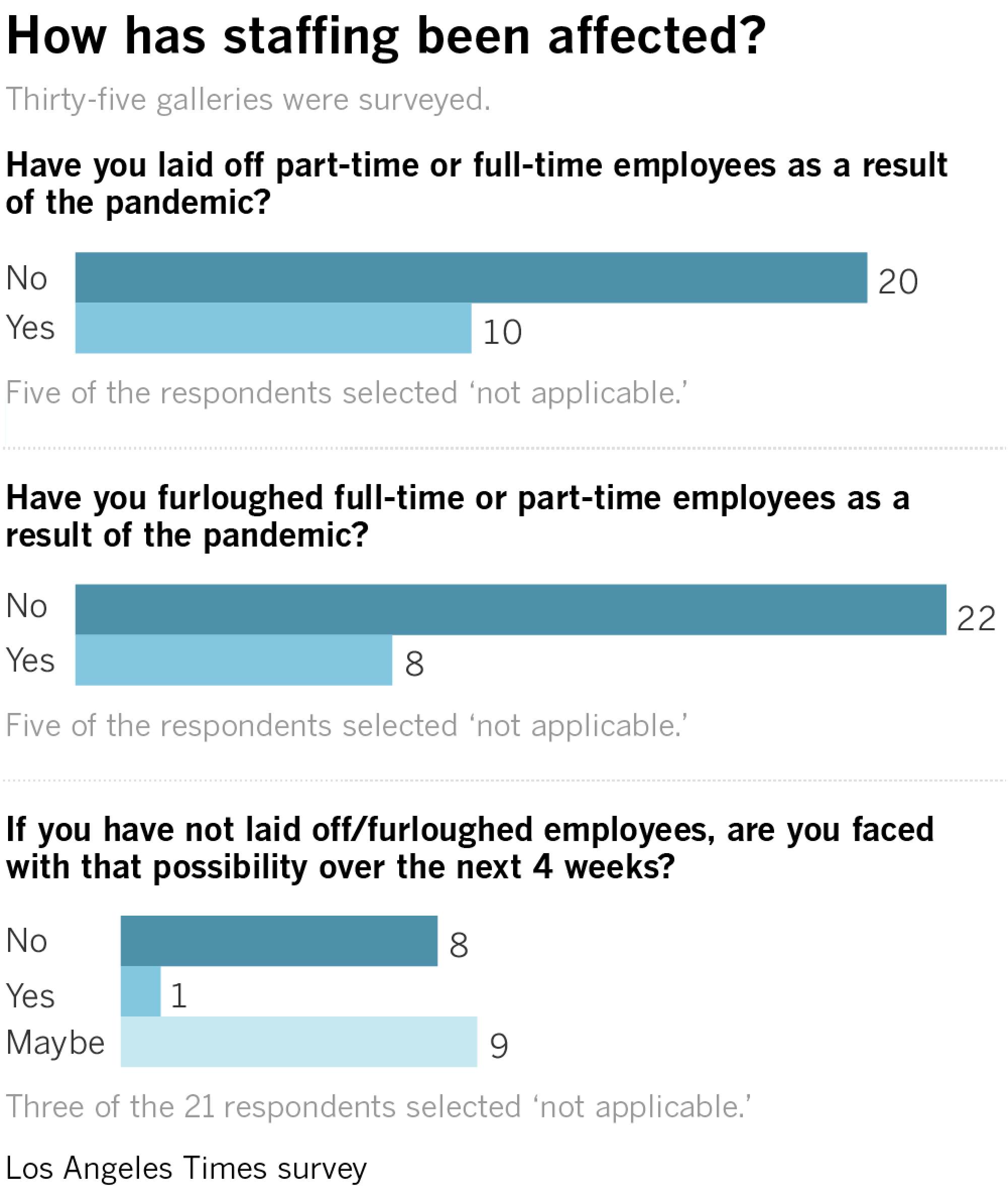

As in every other sector, there have been job cuts. More than a quarter of galleries have cut part-time staffers, and almost a quarter have furloughed employees. But many galleries are attempting to retain staff: 57% of respondents say they have not laid off employees. However, almost a third of the galleries who responded think they face that possibility over the next month.

Nearly 63% have applied for paycheck protection loans; an additional 26% of respondents are looking into doing so. Individually, many say some sort of rent forgiveness or grant program would improve their outlook.

Naturally, revenue is down across the board.

Nearly 89% of the galleries report a decline in sales since the pandemic begun, and 46% have had in-progress sales canceled. Some have continued to sell work, though on a reduced scale.

“We’ve made a few small sales — certainly not enough to keep solvent,” says Peter Fetterman, who has operated a namesake photography gallery in Santa Monica for 25 years and had just opened the doors on an exhibition of photographs by Ansel Adams — a show that had been three years in the making — when the shutdown went into effect.

“Bad timing,” he says, mordantly. “We self-obsessed, narcissistic art dealers will have to take a backseat to the reality of life.”

Going online

As goes the rest of the world, so go the galleries, which, for now, means the internet.

Many have expanded online offerings on their own websites, creating “online viewing rooms” (a fancy way of saying “website”) with additional content. Vielmetter has added videos that feature curatorial walk-throughs of the shows on view. Fetterman used a 3D photography program to create a virtual walk-through of his Adams show. Anthony Cran of Wilding Cran Gallery is working on having San Pedro artist Fran Siegel, who was scheduled to open a two-person show with Paul Scott at the gallery on March 21, lead a video walk-through of the space.

There is also an effort afoot to create a digital sales platform devoted to Los Angeles galleries.

Jeffrey Deitch, the former director of L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), who operates a namesake gallery in Hollywood, is leading the initiative to create galleryplatform.la, a website that will feature a rotating selection of shows that can harness the power of the big galleries to provide visibility for the smaller ones — and help raise L.A.’s profile during and after the crisis.

“Some galleries have big platforms and a 50,000-name mailing list, but many other L.A. galleries don’t have the resources to do a high-tech website,” says Deitch, who had a group show, “All of Them Witches,” cut off by the quarantine. “ “Why not build a platform for everybody?”

L.A. spaces collaborating with Deitch include Château Shatto, Regen Projects, François Ghebaly, Nicodim, Residency Art, Gagosian and Blum & Poe.

“It brings Los Angeles together when things are difficult,” says Poe.

The aim is to have some version of the platform operational in mid-May. “We may put it on [an] existing platform initially,” says Deitch — such as an Artsy or 1stdibs or one of the other online art dealing sites. “But we want to get it done quickly.”

While the site is bound to raise flagging spirits and generate sales, it likely won’t staunch the hemorrhaging.

Though online art markets have seen rising sales over the last half-dozen years, these represent a fraction of larger art sales — even in good times. Nearly 83% of the galleries that responded to The Times survey say online sales will not make up for traditional person-to-person methods. These include gallery openings and, to a larger degree, art fairs.

And the art fair landscape — without air travel and art shipping — has been shaken to its core.

The prominent Art Basel Hong Kong was canceled early in February, and Art Basel’s Swiss fair, generally held in June, has been postponed to September. Whether that fair, along with Art Basel Miami Beach and the cluster of fairs that take place there in December, will be held is anybody’s guess.

Frieze Los Angeles, for the time being, is moving ahead on plans for next February’s fair — but a lot of “what ifs” hang over that enterprise.

Going local

Not all the news is bad. Vielmetter notes that of the various fine arts, it could be the visual arts that bounce back first: “You can’t go to the movies. You can’t go to the theater. You can’t go to where there is a crowd. But you can go to a gallery. We could set it up so there are only two people in the gallery at a time.”

This is already in practice in Seoul, where people are once again beginning to circulate freely: Pace Gallery and the South Korean outpost of L.A.’s Various Small Fires, are already admitting visitors on a controlled basis.

The galleries that do survive will also likely be more locally focused — at least until people feel comfortable flying again.

“A lot of us are exhausted by all the travel,” says Deitch. “In the past year, I was on a different continent on every month and sometimes two continents in a month, and it takes me away from some of the creative work — the writing, the organizing of ambitious shows. This has shown that I don’t need to fly to Paris for the opening. Let’s cut down on some of that and do this through video conferencing.”

In fact, the pandemic could lead to a reconsideration of the art fair model among some art dealers — which is not a bad thing.

“The way we do art fairs is that we ship all these things [halfway] across the world to Europe or wherever,” says one gallerist, who prefers to remain nameless. “Then we send an email to collectors while the works are in transit. Half of the works sell before they even arrive. So the works go on vacation and then we have to turn around and ship it all back.”

In the meantime, the expense (not to mention the carbon footprint) is staggering.

Chimento, who has done 17 art fairs in the past five years, says she wants to make the business of the gallery fun again — and she wants to focus on Los Angeles.

“I’m thinking of spaces like Sue Spaid or Food House,” she says, referring to the scrappy galleries of ’90s-era L.A. “You knew when you went to their galleries that you’d see something you didn’t see before. You knew you’d see this camaraderie among the people.”

For the short term, she’s asking artists to create installations for her gallery’s windows — allowing her to show new work without having to open the doors. She expects to unveil the first installation next month.

Donate the cost of a canceled ticket, take an online dance class, buy a piece of fine art: Here are 22 ways to help artists weather the coronavirus storm.

Indeed, many Los Angeles gallerists are looking ahead — even as they remain trapped in their homes.

Davida Nemeroff, owner of Night Gallery, says she was closing down a show by French painter Claire Tabouret when the quarantine hit. She’s kept busy coordinating a virtual show for Dallas Art Fair that launched on April 14.

And since this year marked the 10th anniversary of the space, which began in a small strip mall storefront in Lincoln Heights, she’s combing her archive for imagery to post to the gallery’s site and social media.

“Our year of celebration,” she says, “is turning into our year of reflection.”

After the lockdown, she hopes to reopen with a group anniversary show.

The title? “Majeure Force.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.