Review: Hammer Museum’s ‘Paul McCarthy: Head Space’ draws a revelatory picture of L.A. artist

- Share via

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Surrealism and Expressionism were dead in the water as viable strategies for making worthwhile new art.

The commercial language of Pop, the strict geometries of Minimalism and the idea-oriented trajectories of Conceptual art had rendered those earlier, messier approaches obsolete. Or so it seemed.

Enter Paul McCarthy. Talk about making a mess!

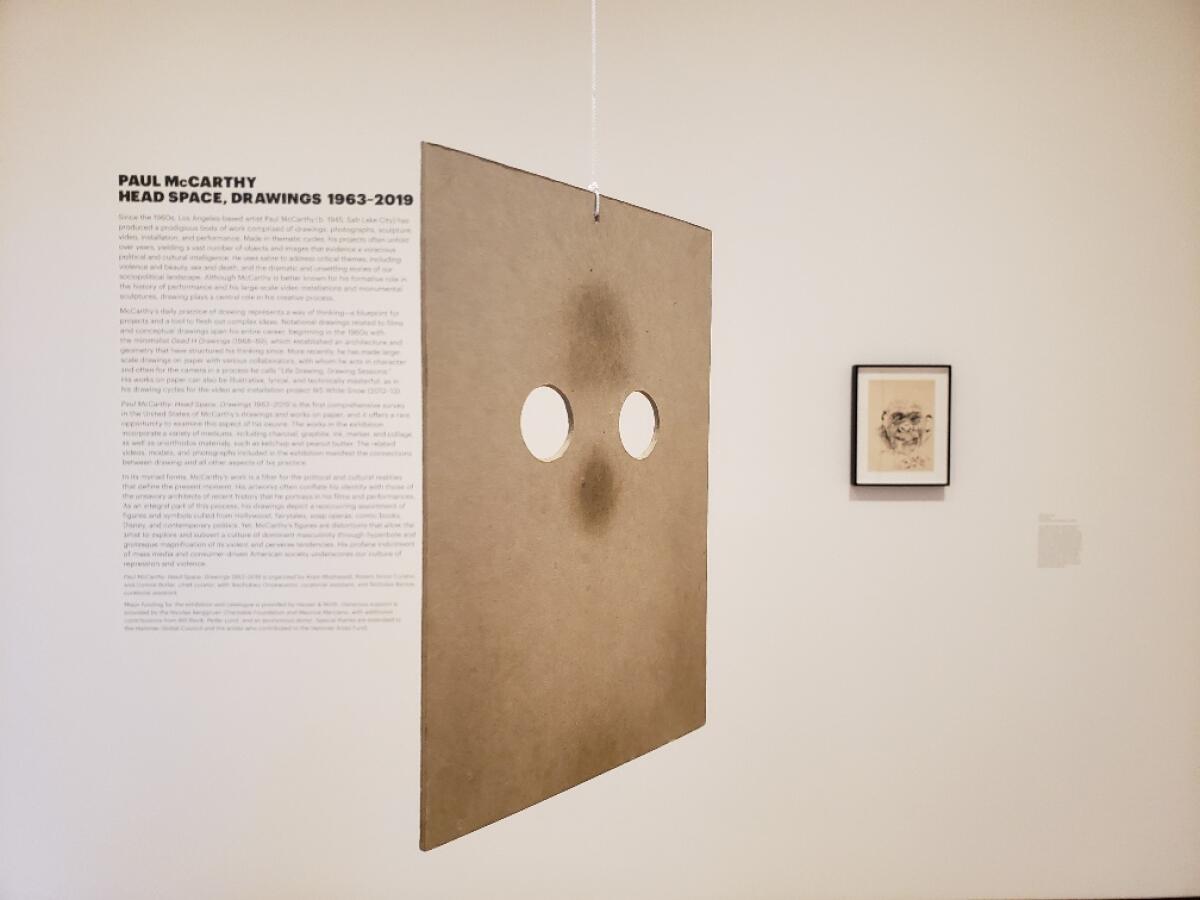

A huge retrospective drawing exhibition — more than 600 works from the last six decades and newly opened at the UCLA Hammer Museum — shows Surrealism and Expressionism roaring to life, beginning in 1963. The show opens with a “Self-Portrait” head — McCarthy, albeit transformed into a gorilla.

The great ape, drawn in sure if short, choppy strokes of black ink on an ordinary sheet of white paper, has one eye open and one eye closed, a benign grin swiped across his robust face. The gorilla’s hairy hands are held before him, as if being put on display.

In this surreal, surrogate self-portrait, the expressionist “hand of the artist” is powerful, confident and crude.

The artist was just 18 when he drew it. American kids, when first introduced to art, are often attracted to the fierceness of Surrealist irrationality and the churning anxieties of Expressionist emotion. Those idioms speak directly to roiling personal issues common to youth, and both are on view in this gruff if genial ape.

But, as the exhibition demonstrates in room after room, McCarthy never let up.

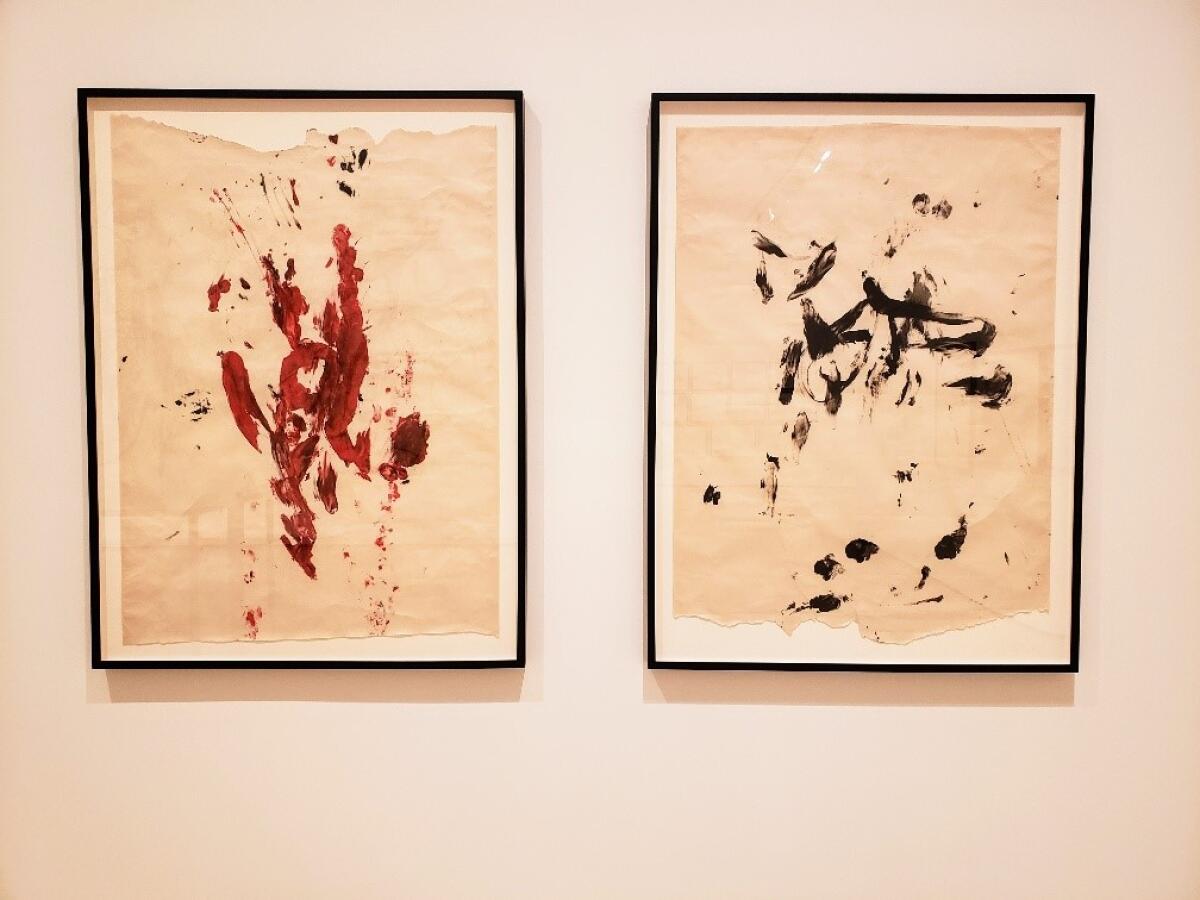

His mark-making is typically brash and gestural, often layering ink, graphite and charcoal with gloppy paint. He used black marker to draw a picture of a body lashed to a post, bound within a suffocating cocoon. He made slashing paintings on paper using acrylic applied with his penis rather than a brush, mocking the base masculine imperatives fueling Abstract Expressionist art.

The Marciano Art Foundation opened in 2017 as L.A.’s newest center for culture. Its abrupt and mysterious closure came less than three years later. What happened?

Drawings purporting to illustrate the terror of the empty void are filled instead with a rush of nightmarish imagery. Elsewhere, a baby’s inchoate gurgling is rendered as driven by outsize, even monstrous sexual urges, all drawn on monumental sheets of paper 11 feet tall and 21 feet wide.

Some McCarthy drawings stand as independent works of art. Others are visual scripts for performance works, which often feature crazed men acting violently while smearing store-bought ketchup and mayonnaise on everything in sight — condiments, which add mass-marketed flavor to dulled social rituals of male power.

Still others represent artistic offerings made by fictional characters in his performances — art conceived as a residue of acting out. Successfully winnowing thousands of works on paper into a smaller yet coherent explication of the artist’s career is no mean feat. Deftly organized by Hammer curators Aram Moshayedi and Connie Butler, with curatorial assistants Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi and Nicholas Barlow, “Paul McCarthy: Head Space, Drawings 1963-2019” inserts videos of several performance works into the mix. They help clarify the L.A.-based artist’s working methods.

Inspiration comes from a wide range of predecessors — Picasso, Brancusi, Giacometti, De Kooning, Hermann Nitsch and many more. A full McCarthy retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art 20 years ago showed him leaving painting behind as his preferred medium, but it was woefully short on drawings. Drawing here emerges as an elastic medium without a singular function.

The final room features a mammoth model of a stage set for an elaborate video performance, as well as scads of related drawings. (McCarthy’s son Damon is a collaborator.) The model is set atop rough wooden tables on grubby carpeting, like salvage from a mad hobby out in a suburban garage, with blinding Hollywood klieg lights arrayed above.

Peer deep into the set’s dense forest of angular trees, and you’ll spot a humble suburban house (modeled on the Salt Lake City home where McCarthy grew up). The shamed expressions of nakedness on figures of Adam and Eve transform this woodland Eden into a creepy hellscape. Another lurking fellow, neatly groomed and looking strangely like Walt Disney, cheerfully greets you to enter a domestic dystopia.

It’s a lot to take in.

There’s a relentlessness to McCarthy’s work over nearly 60 years, and it hammers home the overwhelming physical, psychological and emotional toxicity within a culture that elevates beastly male power above all else. That teenage self-portrait as a gorilla seems painfully timely for the crises of current American life. In hindsight, it ricochets off the unfolding brutalities of the era’s Vietnam War, as well as playwright Eugene O’Neill’s “The Hairy Ape,” a 1922 drama of masculine collapse that’s a staple of many a high school English curriculum.

FRIEZE LOS ANGELES: Highlights from the fair >>

The Hammer show’s first two rooms deserve special concentration. The artist’s youthful explorations lay out parameters for what follows.

Four 1965 ink drawings show the shriveled body of an Indian mummy. The battered corpse of America’s genocidal history lives on.

“Airplane Painting” (1965-66) collages a photograph of a fighter plane into the center of a scarred and abraded sheet of paper, surrounding the weapon of war with clouds of smoky black and smears of bloody red paint. It’s echt Expressionism.

A suite of “Stoned Blue Drawings” (1968-69) — simple graphite and ink line drawings of distorted bodies, pointed daggers, grinning Santa Claus and sex — was executed under the influence of drugs. Like Surrealist automatic drawings, they attempt to sidestep the limitations of the rational mind, which had brought society to the deadly trenches of Verdun in World War I and the hamlet of My Lai six decades later.

“Looking Out, Skull Card” (1968) is a plain piece of cardboard with a pair of eye-holes cut out. Suspended in space from the ceiling, the floating, two-dimensional screen is proposed as a distinctive framework for viewing the ordinary world.

Several neatly typed sheets of performance instructions from 1968 provide arch occasions to witness chaos and destruction. “Tear down a house using a bulldozer,” says one, concluding, “Provide bleachers for spectators.”

The biggest surprise is several schematic architectural drawings, begun in 1968 and continuing for a decade. They look like nothing else in the show.

Labyrinths, an air conditioning unit, the physical constraints of the built environment, cubes as enclosed rooms — no human presence is seen, but its absence is felt. What emerges in drawings of structured, highly formalized systems in which people live is an attention to how life is institutionalized.

For what follows in McCarthy’s career, this is a pivotal revelation. The reason Surrealism and Expressionism were unable to function effectively as artistic strategies in the late 1960s and 1970s was that by then, both had been thoroughly institutionalized. The problem was not that the art’s capacities for eye-opening meaning had been exhausted. They hadn’t. Their institutionalization as historic movements locked them in the past.

If Frieze Los Angeles is the shark, the Felix art fair is a pilot fish. Our critic dives in and finds the waters pretty fun.

Maybe it took an artist working in the hinterlands, far from the rigidly patrolled artistic precincts of Paris and New York City, to recognize the dilemma. Like his younger friend and sometimes collaborator, the late L.A. artist Mike Kelley, McCarthy rages against the machine.

McCarthy’s art is often scatological and purposefully obscene, whether Santa exposed as a creepy predator or Snow White as hardly wholesome and pure. And he doesn’t close down his art’s narrative elements. There is no denouement, no grand finale to events in his enchanted forest.

Creepy Santa never gets his ultimate comeuppance, guileful Snow White never finds her ideal prince. Walt Disney gets merged with the artist, becoming a character dubbed Walt Paul. Everything remains unresolved and open-ended, like a raw nerve that cannot heal. The scale of the work goes from personal to apocalyptic.

This giant drawing retrospective resonates deeply with the awful age through which we find ourselves currently floundering. That’s one sure sign of McCarthy’s artistic significance. “Head Space” can be emotionally and conceptually exhausting, but the work never feels superfluous or redundant.

'Paul McCarthy: Head Space'

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Tuesdays-Sundays, through May 10

Admission: Free

Info: (310) 443-7000, hammer.ucla.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.