Review: L.A. Phil embraces the Weimar Republic’s disruptive art. Trump protesters do too

- Share via

“Since the Weimar debate has continued to repeat itself, albeit with less intellectual brilliance,” Susan Sontag once wrote about the social chaos and unfettered artistic creativity that didn’t end well in Germany between the end of World I and the rise of National Socialism, the era is “as much about the present as it is about the past.”

For evidence of that debate’s currency having become truer than ever, along with the benefit of more intellectual brilliance, there was Esa-Pekka Salonen’s concert with the Los Angeles Philharmonic on Friday night. The Weimar Republic happened to be Salonen’s summer obsession. He put on a big project with his Philharmonia Orchestra in London and conducted a new French festival production of the Kurt Weill-Bertolt Brecht ur-Weimar opera, “Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny,” in Aix-en-Provence.

Now with his old orchestra, Salonen has instigated a new investigation, “The Weimar Republic: Germany 1918–1933.” Along with his two major L.A. Phil programs, the orchestra has added context with “Weimar Variations,” curated by Stephanie Barron and Nana Bahlmann, suggesting ways in which Weimar experiments in visual art, transgender performance, political proselytizing and much else resonates with us today.

Just how timely is this? As intermission came to a close Friday and the L.A. Phil musicians were taking their places onstage at Walt Disney Concert Hall, patrons unfurled a large banner in the section behind the orchestra that read: “Trump/Pence#outnow/Refusefascism.org.”

The L.A. Phil’s Weimar Republic festival is augmenting Esa-Pekka Salonen’s musical explorations with installations and public programs around the city.

The least risk-adverse of orchestras all but asked for it. Among the “Weimar Variations” inspirations was enticing the Los Robles Master Chorale to march up Grand Avenue before the concert, singing Hanns Eisler “Workers” choruses, written to help mobilize left-wing mass demonstrations in 1920s Berlin.

Even so, the Weimar debate is far from binary. The issues are existential and deeply troubling. Did marvelously spiritual, uplifting and morally righteous art of the period transform lives, do harm or mean little in the rise of fascism? How are we to direct our own responses to the art’s lasting delight today?

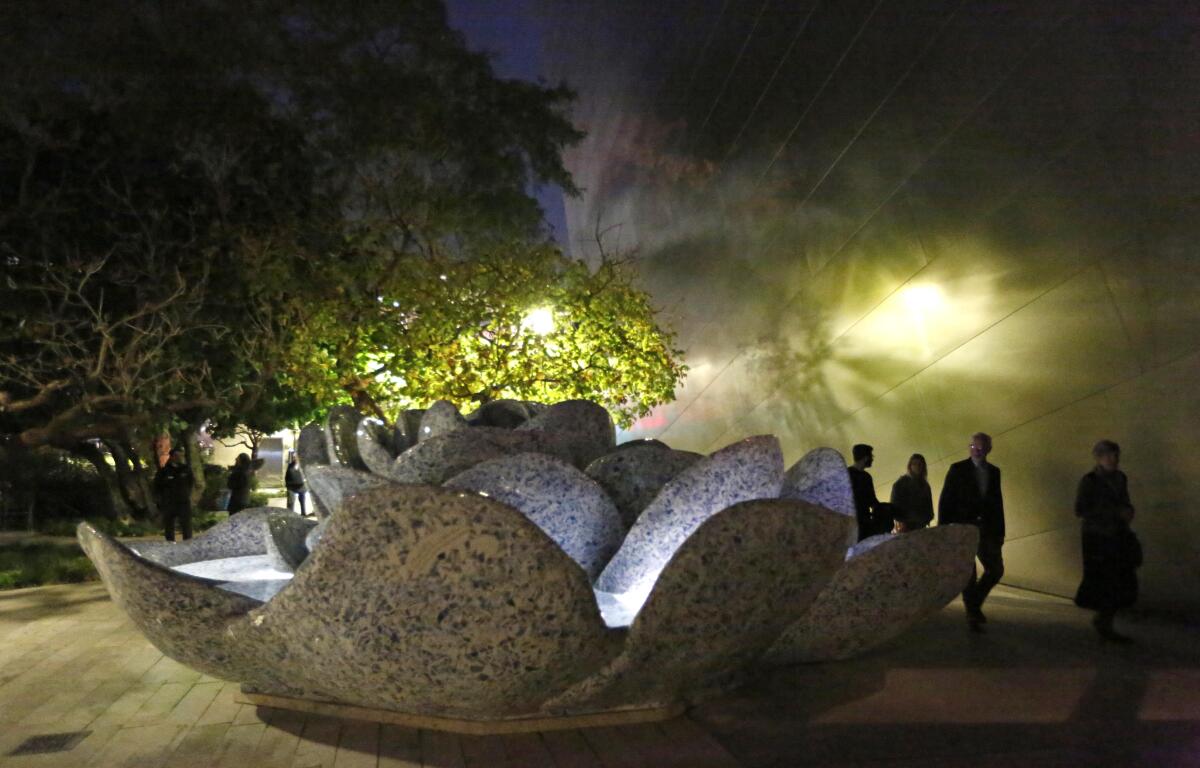

Delight there surely is. Thanks to “Weimar Variations,” Walt Disney Concert Hall has been wondrously transformed into a venue where modern artists interact with those of a century earlier. BP Hall has never looked so fabulous with magnificent Oskar Schlemmer costumes created for a Hindemith ballet in a glorious Frank Gehry-designed display. It’s part of Nicole Miller’s “Transition” installation piece, with laser projections and recordings by singer Kyshona Armstrong and violinist Lady Jess made in a live performance Saturday night.

Through speakers hidden in the foliage, the Disney garden is now a sound installation by Susan Philipsz, in which fragments of an Eisler solo violin passacaglia become transfixing 12-tone bird song. Both exhibitions are open to the public for free daily through Feb. 16.

Salonen’s first L.A. Phil Weimar program turned to Hindemith, Weill and Schoenberg, each of whom contributed to artistic innovation and debate in their Weimar years in a different ways. Schoenberg attacked the hierarchy of tonality with his 12-tone invention (Eisler was his student). Hindemith composed sexually shocking operas (one of which will be given this week in Salonen’s second program). In connivance with Brecht, Weill stoked theater with political assertion and used of popular musical forms (also a feature of this week’s program).

Still, they were true German classicists in the end, raised on Bach fugues and chorales and even insistent that art was the ultimate vehicle of demonstrating order. Nevertheless they were not beyond happily updating Bach with a little cabaret color, or even a garish lot of it.

One overlooked Weimar invention was the jazzing-up of Bach, first done by Hindemith in his adamantly dancable 1921 “Rag Time,” which opened the program. Schoenberg made marvelously candy-colored orchestrations of two Bach chorales a year later. On this occasion, heard after intermission, they served as a gracious musical response to the political banner and rancor in general.

The evening’s other novelty was Weill’s seldom heard Violin Concerto, an early work written in 1924 when the composer was 24. Weill’s concert music, which includes two symphonies, has had but a fraction of the currency of his songs. The concerto is a somber score. The orchestra is confined to winds and percussion, and it has a sour, funereal opening that it never fully recovers from, even in the later more Mack-the Knife-ish moments. Throughout, Weill further searches for a balance between his own scrupulous technique (he was a student of Busoni, who himself proposed a futuristic music founded on on Bachian rigor) and something new.

Salonen and his soloist, Carolin Widmann, who is a fixture on the European concert circuit and prolific recording artist (including a notable account of Morton Feldman’s Violin Concerto that puts American violinists to shame for neglecting it), carefully skirted around the concerto’s awkwardness.

Widmann has a clean, cool tone. She plays with little vibrato. Everything comes out sounding true. If Weill’s winds drowned her out, so be it. Her scrupulous virtuosity needs no promotion. Weill didn’t find a solution here, the pull toward theater was already winning out. But heard in retrospect (the only way we can hear it), the concerto, especially in this excellent performance, had its own sad prescience: a world order was soon to end.

The final work, the symphony Hindemith made out of music from his opera “Mathis der Maler,” needs advocacy. It’s a concert-hall commonplace. But in this Weimar context, it didn’t sound common.

The opera was written at the end of the Weimar Republic, and the symphony conceived when it was already too late: 1934, the year after Adolf Hitler became chancellor. The angelic opening can be heard as angels exiting Germany. Fugue and chorale are evoked as devices to restore peace and order and grandeur.

“Mathis” has long been a Salonen specialty. In a feisty London production at Covent Garden 25 years ago, Salonen and Peter Sellars updated the opera about the painter Matthias Grunewald’s crisis of faith and art in the politically charged Reformation. The surtitles were scrolled across the back of the stage like, well, political slogans unfurled. The performance was modernist, angry, upsettingly of the moment.

Salonen now takes a much broader view. The meaning of art let alone its utility remains an ever-unanswered question. But there is that grandeur and the awe it brings in a luxurious and profoundly philosophical performance like this one. Maybe one Weimar lesson worth learning is that life needn’t be, as it is now, 24/7 debate. Sometimes it helps to let a symphony work its magic in whatever way it can.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.