How Barbie’s Dream House got too dreamy: A Barbitechtural survey

- Share via

Choose your weapon: annihilation by pink or atomic bomb. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, art and design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, and I’m here with the week’s Barbenheimer coverage — and some essential arts news:

Barbie girl in a Barbie world

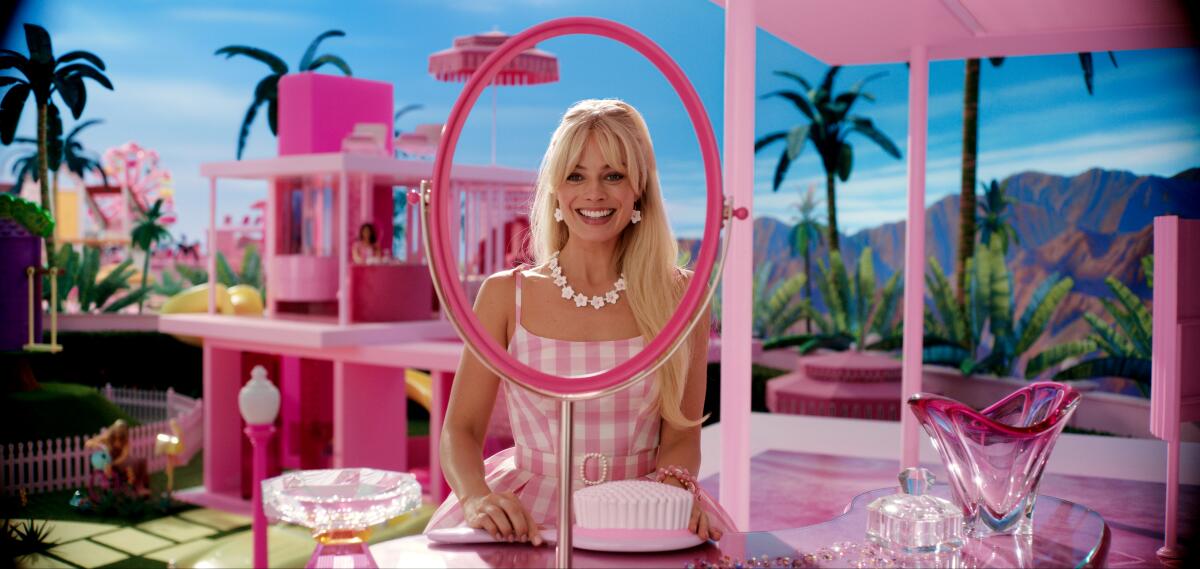

Sorry, Oppenheimer, but when it comes to aesthetics, it’s officially the Summer of Barbie. The movie, as Guardian film editor Catherine Shoard noted in the “Today in Focus” podcast earlier this week, offers something different in a season dominated by “serious, macho, superhero action films,” which she fittingly sums up as “old codgers like Indiana Jones or Tom Cruise jumping off stuff.”

Barbie has infused the summer with a dose of hyperfemininity, not to mention plenty of Pantone #219, Barbie’s proprietary pink — which has materialized in a spectacular array of official and unofficial merchandise: hoodies, pillow cases, pan dulce. Also prominent has been an array of Barbie-adjacent content — like this newsletter! And don’t miss my colleague Justin Chang’s fantastic review, complete with obligatory pun.

In wading through the coverage, I learned a lot from this dispatch by independent fashion writer Marie Lodi, who explores the history of the stiletto mule, and how Barbie helped popularize it. Also on my radar was this piece by Architectural Digest, in which the magazine’s writers used AI to imagine the Barbie Dreamhouse as designed by 10 starchitects. (How interesting that only two of the architects are women. And how interesting that no one has commissioned Architect Barbie to design her own home.)

In lieu of that, we have Airbnb turning a Malibu party house into an improvised Barbie Dreamhouse and making it available for stays — a confection of impossibly pink plastic surfaces and impossibly green AstroTurf. The aerial shots have been irresistible. I imagine the neighbors love it.

Naturally, all of this has gotten me thinking about Barbie Dreamhouses.

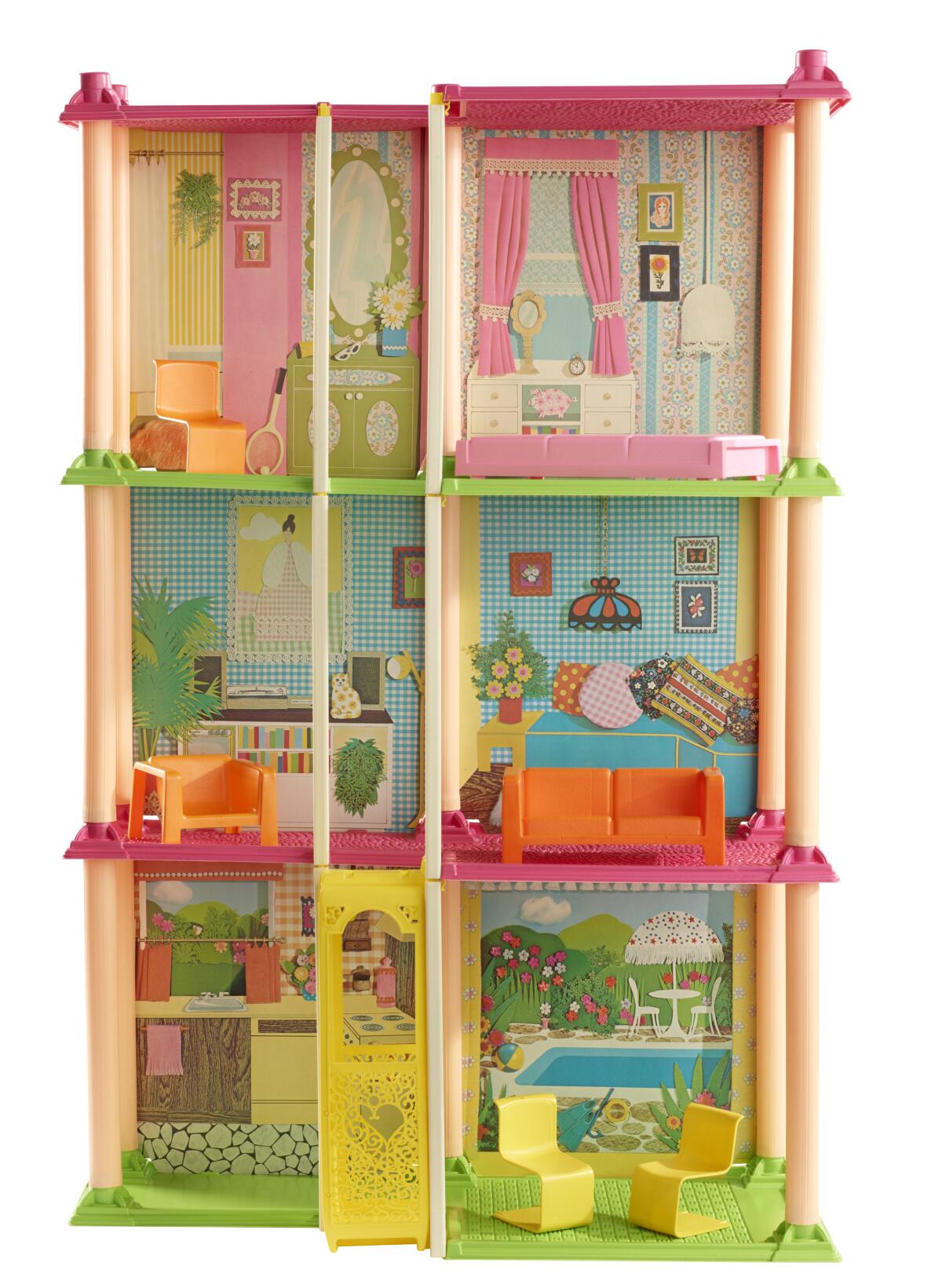

As a kid in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, I was the owner of one such house: the Barbie Townhouse, which was introduced by Mattel in 1974. The three-story home, which came with a “working” elevator (you pulled a string), evoked a certain sense of urbanity. And the painted-on interiors offered a crafty vibe: gingham wallpaper, Tiffany lamps and laminate furnishings in earthy tones.

Particularly noteworthy were the chairs, which were made from a single piece of bent plastic. As design writers Whitney Mallett and Felix Burrichter noted in their 2022 book, “Barbie Dreamhouse: An Architectural Survey,” the miniature furnishing fused elements of Marcel Breuer’s “Cesca” chair with Verner Panton’s more space-age Panton chair, from 1959, an all plastic-chair that employed a cantilever design. (Like many an architectural chair, they looked really great but were completely impractical; Barbie constantly keeled over when placed on them.)

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The townhouse was designed for a gal about town. “Its eclectic décor resembles that of the period’s new singles bars — the so-called ‘fern bars’ exemplified by TGI Friday’s original Manhattan location,” write Burrichter and Mallett in their book, “its potted plants and Tiffany lamps intended to create a clubby, yet female-friendly atmosphere.”

A later version of the townhouse, produced in the 1980s, was more Postmodern in concept, featuring checked black-and-white kitchen floors and a massive sunken tub in the bathroom. It seemed to signal that ‘80s Barbie was ready to ditch Ken in favor of Michael Douglas in his Gordon Gekko phase.

What’s intriguing to me are the ways in which the Barbie Dreamhouse has evolved — growing increasingly fantastical over the decades. This is a history that Mallett and Burrichter track in their fascinating book (which, unfortunately, is sold out — though the New York Times published a good piece in December that gathers some of the stellar photography by Evelyn Pustka).

The first Barbie house, released in 1962, bears no relation to the pink and purple palaces sold now (or to the all-pink color palette of Barbie World in the film). In fact, it’s quite modest: A simple Modernist space, fabricated out of cardboard and contained in a box, it features bright yellow walls, a console TV and a blue easy chair. Pink is minimal — saved for accents such as a cushion and stool. The first Barbie Dreamhouse could be the very aspirational apartment of a recent college grad.

In an essay published in “Barbie Dreamhouse,” architectural historian Beatriz Colomina notes that this first Barbie Dreamhouse was evocative of the Revell Toy House designed by Charles and Ray Eames in 1959. There’s “an escapist impulse to wanting everything designed to be clean and beautiful, joyful and colorful, underneath it anxieties of nuclear annihilation.”

Later houses would also draw from cutting-edge trends in architecture. A Dreamhouse released in 1979 was inspired by A-frame cabins, ditching the designated-use spaces in favor of something more flexible and open plan. The whole vibe, write the authors, echoes Charles Moore’s 1970s Sea Ranch development in Sonoma.

But in the 1980s and ‘90s Barbitecture took a hard turn into the fairy tale, with Dreamhouses saturated in pink and designs evoking Victorian and Neoclassical manses of the late 19th century. It’s a retrograde shift for independent Barbie, who goes from living in an urban townhouse to suburban single family homes — which may not designate a space for husband and child but certainly imply them.

Mallett sees 1979 as an important cultural dividing line — a period of oil shocks and stagflation. “There’s a cultural bifurcation where the pop mainstream and avant-garde intelligentsia are aligned,” Mallett tells me via email, “and then they split.” The year marks a moment when U.S. homes are increasingly designed by builders rather than architects, she adds, and the dawn of the Modern McMansion. It also marks the dawn of Reaganism and Thatcherism and its attendant surge of individualism.

The latest wave of Barbie Dreamhouses, naturally, are informed by digital life, with flamboyant flourishes — such as slides — that are practically made for Instagram (and movie set pieces). As stages, the new Dreamhouses are on point. As homes, they are generally — apart from the slides — unremarkable, evoking the expensively anodyne architecture of clean lines and stainless steel appliances that serve as backdrop to influencer videos.

They also mark another important shift. “They’ve re-aligned, in a way, with a democratization of cultural criticism,” says Mallett, “Easter eggs in Taylor Swift music videos and Wassily chairs on TikTok.”

Barbie may be pure fantasy. She is also a mirror that reflects us right back to ourselves.

In the galleries

Now that I’ve discussed all the plastic, let’s turn to clay. Times contributor Eva Recinos writes about how the material has cropped up in art exhibitions around the country — including a pair of shows in L.A. at the Craft Contemporary and the Jeffrey Deitch. “These two group shows,” she writes, “highlight the themes contemporary clay artists are exploring — namely modern anxieties around industrialization and climate change as well as ancestral memory.”

Artist Judith Bernstein’s paintings are back on view at the Box gallery in the Arts District. The show, organized by fellow artist Paul McCarthy (whose daughter runs the Box), picks up on a series begun during the Trump administration. Times art critic Christopher Knight reports that the canvases, which feature a neon riot of “flaccid penises” and “volatile vulvae,” pack an incisive, feminist punch. “With the specter of fascism all around us again, the bellowing confrontation in Bernstein’s work, a combination of wit and outrage,” he writes, “is nothing if not timely.”

On and off the stage

When the musical “Beetlejuice” landed on Broadway, it was not well received by the critics, writes The Times’ Ashley Lee. And it failed to win a single Tony Award though it was nominated in eight categories. The show has nonetheless been a hit, cultivating a devoted following among young theatergoers — who show up in costume to the shows. Lee examines why that is: “Its storytelling sacrifices nostalgia for the new, specifically in ways that align with Gen Z.”

Moves

The Pollock-Krasner Foundation has announced this year’s grantees and they include California artists Miguel Arzabe, Oliver Lee Jackson, Linda Fleming, Cammie Staros, Cheryl Ann Thomas, Alex Heilbron and Rita McBride (who currently has a work on view at the Hammer Museum).

Elyse Mallouk joins the Broad museum as chief strategy officer and Eva Seta, formerly of the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, joins as director of marketing and communications.

Passages

Tony Bennett, the beloved crooner who left his heart in San Francisco, has died at the age of 96. In honor of the tune that celebrated the city and catapulted Bennett to lasting super stardom, San Francisco erected a statue to the artist. In 2017, music critic Mark Swed caught Bennett, then 90, at the Hollywood Bowl in the company of the LA Phil.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

English actor and singer Jane Birkin, known for her creative and personal partnership with Serge Gainsbourg and for inspiring an Hermès luxury bag, is dead at 76.

Carlin Glynn, whose performance as a madame in “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” after a long hiatus from the stage earned her a Tony Award in 1978, has died at 83.

João Donato, a composer and arranger who was an early pioneer of bossa nova in the 1950s, is dead at 88.

In the news

— Quite the fascinating story about Shelby White, the antiquities collector who has been a generous supporter of the Metropolitan Museum of Art — and also a regular buyer of looted objects.

— New York’s Whitney Museum has jacked up its ticket prices, becoming the most expensive museum in New York.

— Hyperallergic breaks down NYC’s priciest cultural institutions.

— Jessica Zack of the San Francisco Chronicle has an interesting story about Frank Bowling, who is currently the subject of a solo show at SFMOMA — the first major U.S. survey of the artist’s work.

— Plus, the Chronicle’s architecture critic John King weighs in on the doom loop, noting that most media reports about SF “reduce a city of 49 square miles to a handful of lurid set pieces.”

— Crypto.com Arena is trying to squeeze the wallets of the Richie Riches with new suites that allow ticket holders to enter the arena through the same underground tunnel used by players and performers.

— How ancient skywells keep Chinese homes cool.

— A very sad office-to-housing conversion in the Bay Area goes viral.

— Faculty are leaving a Florida college dismayed over changes implemented by Ron DeSantis, leaving the college without enough faculty to teach course offerings.

— What Twitter has meant for Latino journalists.

And last but not least ...

Three words: Earring Magic Ken.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.