Can you separate the art from the artist? ‘MJ’ puts it to the test

- Share via

T.S. Eliot called April the cruelest month, but the calendar appears to have democratized the badness. I’m Times theater critic Charles McNulty, filling in for Carolina A. Miranda as host of this arts omnibus. Please join me in taking a much-needed break from doom-scrolling to survey the highs and lows of an eventful week in the arts.

The man in the Broadway mirror

An old conundrum has reared its head on Broadway. The question of whether it’s possible to separate the artist from the art has been on my mind since I saw “MJ,” the jukebox musical about Michael Jackson that treats its subject with sequin gloves.

The show, which was recently nominated for a passel of Tony Awards, features a book by two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Lynn Nottage. Her track record of dialectically complex work (“Ruined,” “Sweat”) made me eager to see how she would approach the biographical baggage of an entertainer who has only accumulated more unwanted luggage since his death in 2009.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox every Monday and Friday morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But “MJ,” which is produced “by special arrangement with the Estate of Michael Jackson,” tells a carefully edited version of the singer’s story. It’s a typical jukebox musical, in which preexisting hits are stitched into a narrative like rhinestones on a denim jacket. The difference is that there’s public relations rehab mixed into the usual formula.

The show is framed around Jackson’s struggle to launch his 1992 Dangerous tour, which was to be the tour to end all tours. Flashbacks to Jackson’s childhood and teenage years require that three performers play him. But the star of the production is unequivocally Myles Frost, who moonwalks away with the musical as the adult king of pop.

This timeline allows the creative team to skirt accusations of child sexual abuse that exploded in the media after the Los Angeles Police Department opened an investigation in 1993, when the Dangerous tour was already underway. Yet “MJ” isn’t just about the indelible music and mesmerizing virtuosity of an artist who was always determined to transcend his fans’ (and his own) sky-high expectations.

The musical makes an insistent case for Jackson as a sympathetic victim. Growing up, he’s subjected to the brutal tyranny and physical abuse of his father, Joe Jackson. The legacy of this violence is apparent in the relentless, unforgiving perfectionism that drives Jackson to go beyond his physical and psychological limits.

The racism of the music industry, no more escapable than the racism of society as a whole, is something Jackson is forever butting his head against. And his myriad eccentricities, combined with his acute sensitivity, leave him exposed to the rampages of a predatory media.

All of this is true. But in avoiding the elephant in the room, the show comes off as distractingly manipulative. At one point I wanted to shout, “Would you quit the reputation laundering so I can enjoy the music in peace?”

Welcome to another chapter in the ongoing ethical dilemma of scandal-scarred male artists and the art we just cannot quit. I’ve tackled this issue before and recognize that there are no definitive answers. How much you know, how much you care, how invested you are in the artist, how much dust has settled — the factors are many, and everyone is a jury of one.

The subjective nature of these determinations is unavoidable. Yet I still found myself bewildered that a few in my social media community who were vociferous in their condemnation of Woody Allen, vowing never to watch one of his films after seeing last year’s HBO documentary “Allen v. Farrow,” were extolling the pleasure of “MJ” and the gift that keeps giving in Jackson’s music.

I’m sure these online acquaintances also saw the HBO doc “Leaving Neverland,” which examines the singer’s involvement with two boys who claim to have been sexually abused by Jackson. Perhaps they’d done a comprehensive review of the evidence of sexual misconduct and weighed in other biographical material, but the appearance of inconsistency was unsettling.

I’m an avid reader of biographies, though I’m not particularly interested in autopsies of misdeeds. How obstacles were overcome and greatness achieved fascinates me more than dirty laundry. But I also know that I tend to be more lenient toward artists whose work has meant a great deal to me. As jurors in these cultural trials, we wear our biases on our sleeves. Whom we indict or excuse says as much about ourselves as it does about our fallen idols.

As a playwright, Nottage has been a moral beacon, wrestling with problems of race, gender and class with as much complexity as compassion. She’s earned this payday at the jukebox cash machine. But hagiography is beneath her.

Still, if you haven’t listened to Jackson in a while, you’ll remember just how much you love his sound. One thing “MJ” makes clear is that the music will never die. The parade of hits — from the Jackson 5’s “ABC” and “I’ll Be There” to the solo breakout records “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” and “Rock With You” to the arrival of “Thriller,” the album that turned a phenom into a legend — can’t help but leave an audience breathless.

Of course, not even the most stellar Broadway performers can duplicate the miracle that was Jackson. Wisely, the production, directed and choreographed by ballet veteran Christopher Wheeldon, puts the dancing ahead of everything.

“MJ” is most theatrically alive when it’s liberated from the cliches of biographical drama and allowed to move freely. When the show becomes one with the music, the effect is ecstatic. Genius doesn’t need a defense attorney — though knowing “the dancer from the dance,” to quote Yeats, remains a never-ending challenge.

On the stage

Bringing exceptional work wider notice is the best aspect of being a critic, but pans are part of the job. The misbegotten production of “King Lear” at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts — a tragic masterpiece treated as a circus farce — deserved the strongest rebuke. I began my review accordingly: “Every so often in the career of a theater critic, a production becomes a crime scene and the critic is thrust into the role of medical examiner to determine how the victim died.” A wasted Joe Morton, who plays an unusually frolicsome Lear, isn’t the only casualty of this careening deconstruction.

The pandemic has only made the housing crisis in America more acute, as Angelenos know as well as anyone. The Times’ Jessica Gelt had a conversation with Mark Valdez and Ashley Sparks, creators of the immersive performance work “The Most Beautiful Home … Maybe,” about what theater can do to find solutions to a problem that is only growing more widespread. Produced by Minneapolis’ Mixed Blood Theatre, this piece brings an interactive, community-building vision to REDCAT to take up a simple yet necessary question: “What if everyone in this country had a home?”

Water is a crucial element in Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” and so it makes perfect sense that the new production of Mary Zimmerman’s theatrical adaptation at A Noise Within would center around an actual pool. The Times’ Melissa Hernandez spoke with Julia Rodriguez-Elliott, producing artistic director of the Pasadena theater, about the design and technical challenges of making this a watertight reality onstage.

An icon turns 100

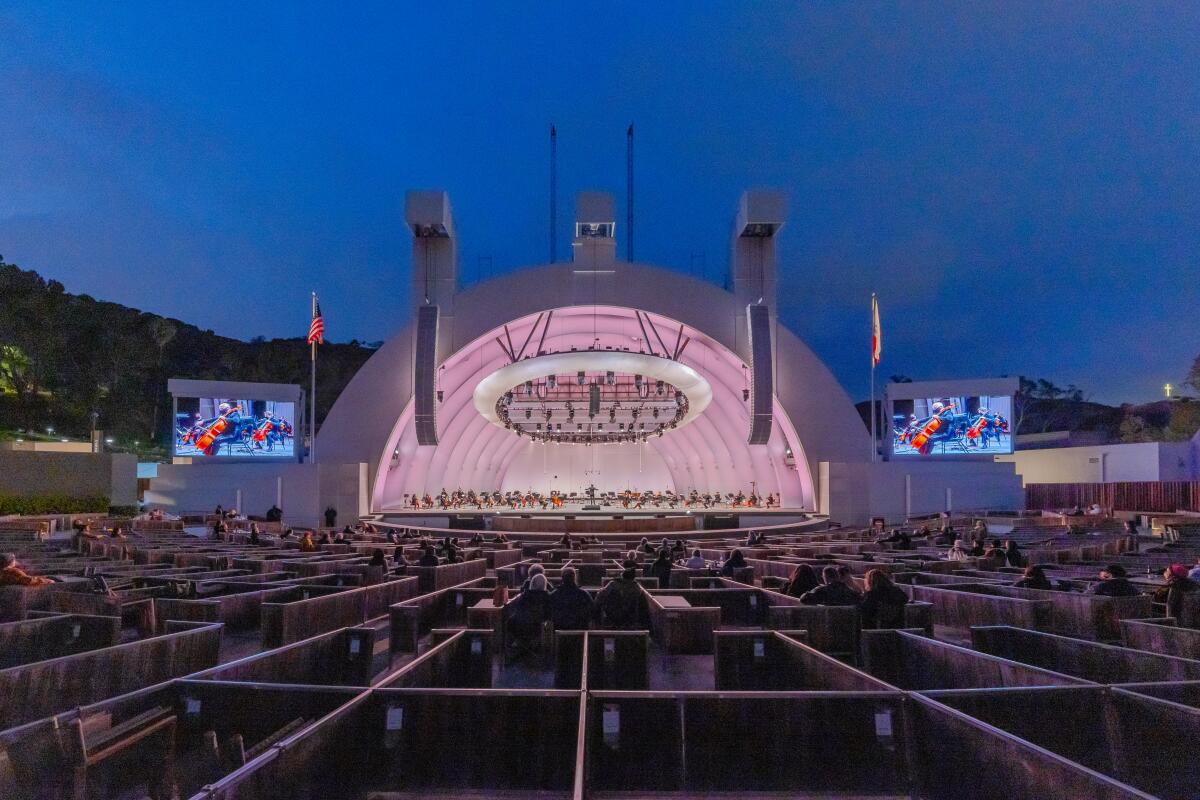

The Hollywood Bowl is celebrating its 100th anniversary, and we’d like to hear from readers about their favorite memories for a special edition of Sunday Calendar. If you tell us yours, we promise to tell you ours. (Hint: Mine’s a musical.)

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Art and architecture

Times art critic Christopher Knight checks out an exhibition of paintings and sculptures by Kevin Beasley, who works wonders with polyurethane resin. The toxic plastic has been used by other artists, but what distinguishes Beasley, in Knight’s words, is the way he “wields resin like an embalming material — an industrial-strength amber for trapping life’s transient flies.”

In walking around her lush, green neighborhood, Gelt notices “a striking disconnect between the perils of climate change and Angelenos’ behavior in the face of it.” In a timely, thought-provoking essay, she examines how Hollywood helped make a green lawn “fundamental to the foundation of the California dream.”

Let’s go fly a kite: Times staff writer Deborah Vankin has a preview (with magnificent photos) of Community and Unity People’s Kite Festival, which launches “a veritable art gallery in the sky with kites of all varieties — enormous diving dragons, swooshing centipedes and tiny diamonds in an explosion of color.” But it’s not all recreational frivolity. This free public event at Los Angeles State Historic Park is “also a powerful statement meant to celebrate equitable access to public land in L.A. and advocate for its preservation.”

The story of how a “granny flat” or ADU in South Pasadena brought a family closer together is vividly captured in Times staff writer Lisa Boone’s report, which has the coziest set of sun-dappled photos.

And Image Editor-in-Chief Ian F. Blair translates the language of L.A.’s apartment signs into a fascinating story on the architecture and design of everyday city life.

Classical music

Times classical music critic Mark Swed writes about works by two composers, Ellen Reid and Gabriela Ortiz, that meditate on environment in its various physical, cultural and spiritual manifestations. Here’s a taste of Swed, lyrically soaring, on Reid’s “Floodplain”:

“In ‘Floodplain,’ the orchestra heaves and releases, like a river of sound overflowing its banks and then evaporating. Tremolos are everywhere, in luxuriant strings and piquant winds and skittering percussion. Richly expressive solo passages for violin and cello might be heard as the living creatures on the scene — probably not human, though, as they are too absorbed into the texture to seem like outsiders. Incandescent melodies, or hints thereof, emerge only at the end, hinting at floodplains harmonized into the environment.”

Moves

Charmaine Jefferson is set to take over as chair of CalArts, replacing Tim Disney, who is stepping down after eight years in the role. A former executive director of the California African American Museum, Jefferson will be the first Black woman to serve as CalArts chair.

Susana Gonzalez Edmond has joined the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach as chief officer of government and external affairs. Previously, she served as chief of staff to Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia.

The MOCA Union, the first labor union at the Museum of Contemporary Art, represented by AFSCME Local 126, ratified its first collective bargaining agreement with museum management this week. The agreement covers more than 80 workers in a variety of positions.

Jessica Hanson York has been named executive director of the Mingei International Museum in San Diego’s Balboa Park. She succeeds Rob Sidner, who had been in the role for 16 years.

Ladies and gentlemen, the weekend

“Hamlet” and Verdi’s “Aida” make the cut of Times listings coordinator Matt Cooper’s weekend picks.

And last but not least ...

Some happy cultural news involving the Believer magazine, which is back with its original publisher, McSweeney’s, after a postmodern twist that had it momentarily under the control of a digital marketing company that’s deep in the sex toy business.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.