Dhani Harrison awakens new sounds and spirituality with help from Tuvan throat singers

- Share via

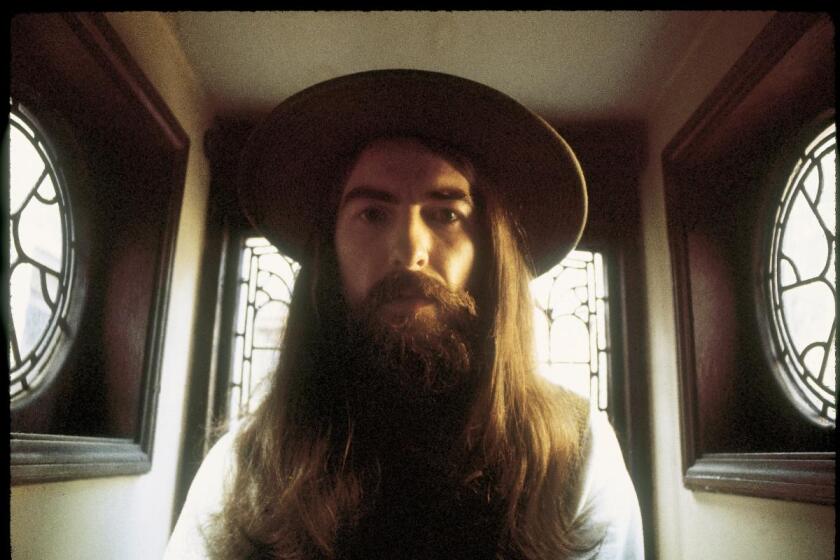

Dhani Harrison can’t help that he sounds just like his dad. It’s not only his singing voice, or his aesthetic voice as a songwriter. When he enthuses about spiritual healing, oneness with nature and collaborating with master musicians from ancient, non-western cultures, he is the very echo of his old man.

But one immediately senses with Harrison, whose father was George Harrison, that he comes by his inheritance honestly. All those years making music with his dad, growing up around meditation practice and Indian classical music and a record label that promoted “world music” to this side of the world culminated in an apple that hasn’t fallen far from the tree — a tree whose eclectic roots grew deep and whose branches reached far from home.

Harrison’s latest project is “Dreamers in the Field,” a collaboration with the Tuvan throat singing ensemble Huun-Huur-Tu. The album was just released on Dark Horse Records, the label George Harrison created in 1974 and which Dhani revived in 2020. In a poetic echo, this year marks the 50th anniversary of the label, of the album “Shankar Family & Friends” and of the accompanying Dark Horse Tour that the elder Harrison took with Ravi Shankar and an Indian orchestra.

“My father obviously did a lot with world music,” says Dhani Harrison, 45, via Zoom from his home in England. The younger Harrison has released several albums as a solo artist and with various bands, but this was his first time on Dark Horse — and “it felt right that this world music went to its home there.”

Harrison has an omnivorous musical diet; only someone who has already listened to a lot of throat singing music would get served Huun-Huur-Tu by an algorithm. But that’s what happened shortly after Harrison finished a tour in 2019 when he stumbled on a performance by the group, who also perform using traditional Tuvan instruments. Instantly fascinated, he looked them up online and found several videos of live performances.

“I literally watched them every night,” he says, “and I got obsessed with it. The music was just so healing, and it felt like exactly what my body needed. It felt really beneficial to just listen to these masters singing, and then it started to inspire me to try and learn how to do their certain types of throat singing.”

He emailed Carmen Rizzo, a producer who has worked with everyone from Michael Jackson and Seal to Ryuichi Sakamoto, and who made several albums with Huun-Huur-Tu. Harrison put it out there that he would love to help on any of their future projects, and Rizzo said: “Well, actually, I’ve got nearly a whole record of stuff that I recorded with them for the last album but we never used. It’s just sitting on a hard drive.”

Rizzo flew over from Prague to play the recordings for Harrison — some were traditional songs he was already familiar with and others were new to him, including one (“Mazhalyk”) with a stately string arrangement. Harrison was inspired to add piano, synths, drums and guitar parts as well as backing vocals, and to create a few new songs. Rizzo took that material to Huun-Huur-Tu in Slovakia, where they recorded vocals on Harrison’s tracks in a hotel room after a concert.

It was all done remotely, and Harrison only ever communicated with the group by FaceTime — but then again “it’s a traveling record,” he says. “That’s the nature of their music: it’s caravan riders, and it’s the Ulatay River. It’s all traveling music. So it’s natural that it went so far before it got finished.”

The final record is like a soundtrack to an invisible movie — Harrison has, in fact, scored several films — with modern pulses and grooves ebbing and flowing with these Tuvan vocals that sound both intrinsically human and primal and at the same time from another world.

“This style of singing comes from a time before language,” says Harrison. “They’re re-creating the sound of a bird, or the sound of a horse, or the sound of a stream, or the sound of wind in the mountains. So it’s got the nature force vibes all the way through it.”

Harrison learned many new things about the human body — like the fact that we have sympathetic vocal chords, and about the hidden capacities of both the head and chest cavities, and how the constructive frequency “amplifies these whistle sounds and suddenly you can be singing three notes at the same time inside one body.”

When he plays this music for his friends, “they love it,” he says, “but then they feel immensely overwhelmed, and either cry, or laugh — it’s something that has to come out. It feels like it’s shaking you on the insides, and it’s going in all the corners and getting all of the dust that’s been building up and sweeping it toward the door.”

A lot of stuff has been building up for Harrison, who recently moved back to England after nearly 20 years in Los Angeles. He jokingly referred to it as a process of “rewilding” into the English countryside.

He was on his way to Japan in early 2020, shortly after his initial call with Rizzo, and was planning to spend 10 days in Australia when the COVID-19 pandemic shut the world down. Soon, 10 days turned into four months.

“It was paradise,” he says. “I got locked down in the nicest place. And it wasn’t, like, Melbourne — I was out in the countryside. So I was very lucky.”

That’s when he started writing a batch of original instrumental songs that became his newest solo album, “Innerstanding,” which came out quietly last October. He eventually made it back to England that summer, “and then it was just lockdown after lockdown after lockdown.”

Harrison channeled his frustrations at being “detained” into what he considers “a tough record. It’s a hard record, and it’s definitely standing its ground in terms of what it believes in.”

He did not elaborate, but the somewhat riddling lyrics — which he added last — suggest an aggravation toward governments that impose a “new religion,” splitting society into tribes and inflaming the conflict.

In keeping with Harrison’s breakout solo album (“In///Parallel” from 2017), this new record throbs with electronic beats and grungy electric guitar — much of which was performed by Graham Coxon of the band Blur — but with cinematic arrangements and influences of Indian musical grammar providing a kind of mantric spell under Harrison’s still-youthful tenor and lilting falsetto.

It’s an aggressive unity album, “written from the end of the before to the after times when the whole world changed,” he says, “and it’s been very different ever since.” But the message, he adds, is simply: “My light, my love in everything.”

A few weeks ago, Harrison turned up at the end of Eric Clapton’s set at the Royal Albert Hall — the first time he was on that stage since November 2002 to participate in “Concert for George,” the all-star memorial concert for his father, who had died a year earlier. He joined Clapton on the classic George Harrison song “Give Me Love,” and it was “really moving,” he says, “to be back up there.”

He’s already planning another world music soundscape album with Rizzo, this time with the Bulgarian Women’s Choir of Sophia. He wants to get out and perform “Innerstanding” on stage and is currently finishing the mix of a live concert film in Dolby Atmos. High-tech and ancient culture tend to mingle in the Dhani Harrison workshop — healing and aggression.

But, he says — sounding a lot like his father — “we have to aggressively love each other. We have to make a point of actively trying to unite.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.