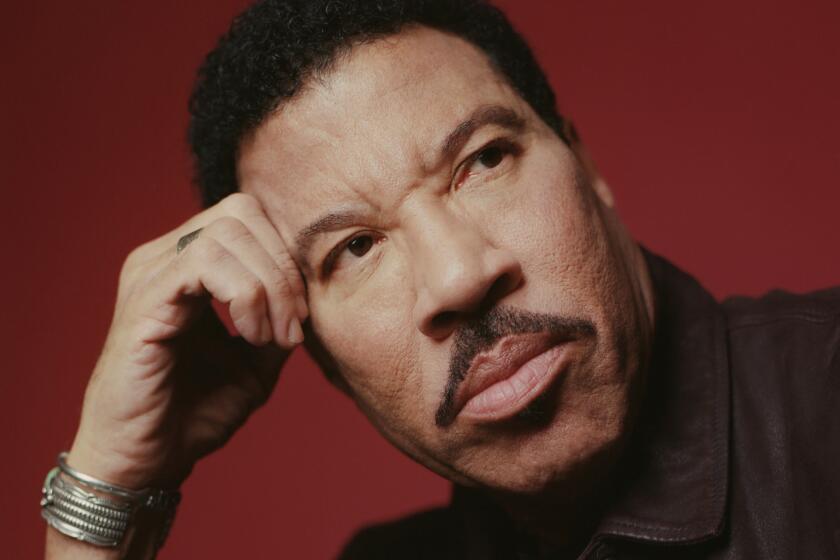

Lionel Richie, Prince and a grumpy Bob Dylan: The untold story behind ‘We Are the World’

- Share via

As he took in a recent screening of a new documentary on the making of “We Are the World,” Lionel Richie found himself — even now, four decades after the all-star charity single was released — gripped by a creeping sense of anxiety.

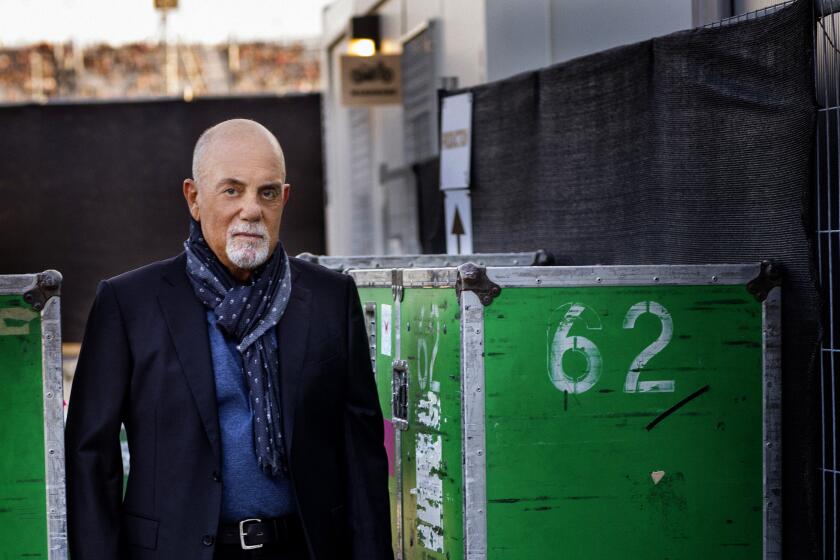

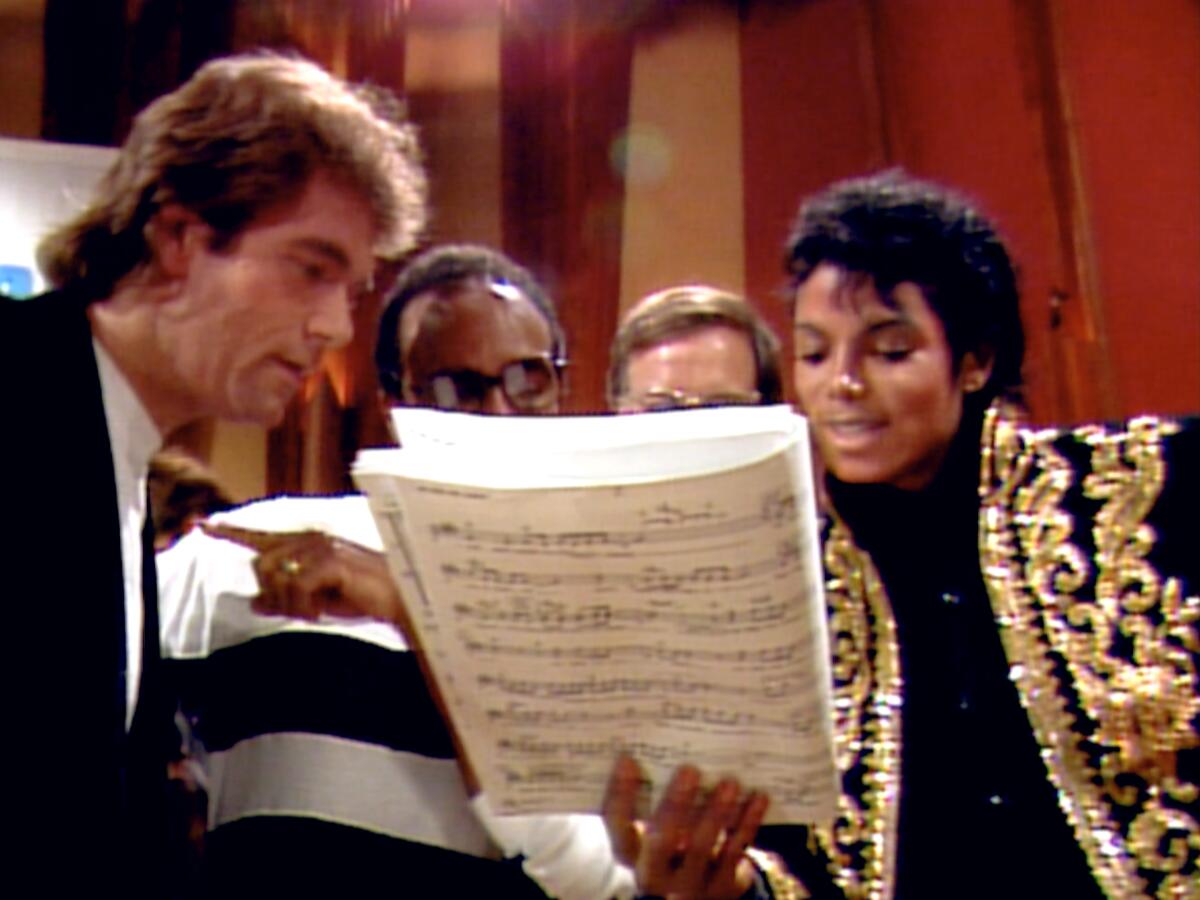

“You have to understand: It was an impossible thing to pull off,” the veteran pop-soul singer says of the one-night recording session that gathered 46 famous artists at the historic A&M Studios on La Brea Avenue on Jan. 28, 1985. The mission, timed to an influx of talent to Los Angeles for that evening’s televised American Music Awards, was to cut the song Richie and Michael Jackson had written together to raise money for famine relief in Africa; the challenge was getting it done before the assembled A-listers — among them Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Wonder, Paul Simon, Cyndi Lauper, Billy Joel, Tina Turner, Huey Lewis, Kenny Rogers and Bob Dylan, all under the direction of producer Quincy Jones — scattered the next morning.

“Folks were booked to go home,” says Richie, who remembers eyeing a clock on the studio wall around 2 a.m. and realizing how much work was left to do — “and we didn’t have another day to do it,” he says. “So I’m sitting there halfway through the movie like, ‘Holy crap, we’re in trouble.’ I’m sweating it, and it’s 40 years ago,” he says, laughing. “I had to remind myself: ‘The song came out, Lionel. It was successful. We did it.’”

Indeed, “We Are the World” was an instant smash, selling a reported 800,000 copies in just three days and topping Billboard’s Hot 100 for four consecutive weeks. Credited to USA for Africa, the song went on to be certified quadruple platinum and won Grammy Awards for record and song of the year; it’s also said to have generated tens of millions of dollars in much-needed humanitarian aid.

Now this iconic ’80s artifact is the subject of “The Greatest Night in Pop,” an entertaining and surprisingly moving doc from filmmaker Bao Nguyen that premiered this month at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, before arriving Monday on Netflix.

Drawing on archival footage and new interviews with Richie, Springsteen, Lauper, Warwick and others, the movie offers an immersive, richly detailed account of the song’s high-pressure creation — not just that evening at A&M but over the weeks of advance planning required to figure out whom to enlist, where and when to do it and how to keep it secret.

Nguyen, whose previous films include 2020’s “Be Water” (about the life and work of Bruce Lee) and 2015’s “Live From New York!” (about the early years of “Saturday Night Live”), says “there’s almost a heist element” to the story as the people involved carefully plotted out the job.

Yet “The Greatest Night in Pop” also makes a strong case for the artistic value of “We Are the World,” which after countless parodies and emulations can be hard to hear today with fresh ears. Here, though, is an opportunity to listen as some of the finest vocalists in history take turns trying to outdo one another in just a line or two: Willie Nelson stretching the word “God” to cosmic-country lengths, Dionne Warwick nudging ever so slightly ahead of the beat, Ray Charles finding notes you didn’t even know existed.

Don’t let the easy-listening ballads and pastel sweaters fool you: Lionel Richie, starting his fifth season on ‘American Idol,’ is a true Black music pioneer.

“I’m just gonna put it right out there, OK? There’s no Auto-Tune anywhere in the performance of that song,” says Richie, 74. “Period. In other words, Bruce is killing Bruce. Ray — that’s just Ray. That night you were laid bare, and there was nothing to save you.”

Asked if he’s ever encountered a young singer auditioning with “We Are the World” in his role as a judge on TV’s “American Idol,” Richie laughs. “You know what, no one’s ever gone that route,” he says. “Thank God.”

As the documentary shows, “We Are the World” was conceived as a kind of American counterpart to “Do They Know It’s Christmas?,” the British charity single released in late 1984 by an all-star supergroup that included George Michael, Phil Collins, Sting and Boy George, among many others.

“Harry Belafonte called me and said, ‘What are we going to do about saving Black folks?’” Richie recalls of the legendary performer and activist who died last year at age 96. “That was my wake-up call: ‘OK, he’s speaking to me right between the eyes.’” Richie, then riding high as a solo act after his years fronting the Commodores, reached out to Jones, who reached out to Jackson, with whom the producer had made the blockbuster “Off the Wall” and “Thriller” albums.

In contrast with “Do They Know It’s Christmas?,” the two songwriters weren’t aiming to create a song tied to a specific time of year. “Michael and I decided from the beginning that this should be an anthem,” Richie says. “And an anthem means we’re looking for a forever song.”

“We Are the World,” which alternates verses performed by various soloists and a refrain sung by the entire group, is also steeped in African American tradition — in the sensual lilt of R&B and the communal thrust of gospel music. “When that choir comes in, it’s undeniable,” Richie says. “You can’t help but go to church because that’s who we are — we’re church people.”

Nelson George, a longtime music journalist and filmmaker, hears echoes of Motown in “We Are the World,” which Wonder helped shape as an arranger. “Michael, Lionel and Stevie, all three of them were graduates of that school,” says George, whose 2023 doc “Thriller 40” examines the making of Jackson’s masterpiece. “And the Motown school was all about the Black root that can leap over the boundaries of record-business prejudice.”

With the song in place, “The Greatest Night in Pop” follows the efforts of Richie’s manager, Ken Kragen, to recruit as many bold-faced names as he could for the session — work that continued right up until the appointed hour, according to Lewis, who recalls singing the song for the first time that night with everyone huddled around a piano with Wonder at the keys.

“You could see it register on Stevie’s face as he heard all those voices, because he didn’t know who all was there,” Lewis tells The Times. “After that first run-through, I remember he just went, ‘Wow, so many stars.’”

As a soloist, Lewis ended up singing a line originally meant for Prince, who’d been invited to take part but didn’t show up — one of the great what-ifs in pop-music lore given Prince’s notorious rivalry with Jackson. Richie is philosophical about the Purple One’s absence.

“Artists like to be in control of our environment, and when you walked into ‘We Are the World,’ you were not in control,” he says. “For Prince, that was a little too much out of control for him to deal with.”

Joel, who performs with Stevie Nicks on Friday at SoFi Stadium, on the inspiration for ‘Piano Man,’ farewell tours and his ‘70s hit he now calls ‘dreary.’

Lewis, whose golf-bro classic “Sports” had topped Billboard’s chart in mid-1984, admits he was “out-of-my-mind nervous” during the recording session: “I was a rookie, man, and I was just supposed to sing in front of Stevie Wonder and Al Jarreau and Lionel Richie? Forget about it.”

Yet even a pro as seasoned as Dylan was feeling uneasy in such a heady atmosphere. One of the documentary’s delights is its many shots of the folk-rock giant looking deeply uncomfortable amid so many of the day’s pop stars.

“I think he got overwhelmed because he was surrounded by all these powerful singers,” Richie says. “So when it came time to do his part, he tried to sing it instead of Bob just doing it like Bob. It took him a minute to realize: ‘Oh, you want me to sound like myself?’”

Some of the archival footage in the film will be familiar to viewers with long memories from an earlier making-of doc that HBO ran back in 1985 (with a very poofy-haired Jane Fonda as host). But Julia Nottingham, who produced “The Greatest Night in Pop,” says the new movie benefits from hours of unearthed behind-the-scenes audio recorded by journalist David Breskin, who was on the scene to report a story for Life magazine.

“He had his Dictaphone on from the minute Lionel and Michael started writing the song and Ken started doing logistics all the way to 8 in the morning, when they left the studio,” Nottingham says. “That’s something the world has never heard before.”

The movie also benefits, of course, from Richie, one of music’s most appealing conversationalists. (He tells a great story about Jarreau getting tipsy before the musicians had even done anything to celebrate.)

Even so, going back over his memories of “We Are the World” was a bittersweet experience for Richie, the singer says, given the number of participants who’ve died in recent years, among them Jackson, Jarreau, Belafonte, Turner, Rogers, James Ingram and several Pointer Sisters. Did it make him wonder whether such a song could be recorded today? It did, and he has his doubts.

“I don’t know that the song could survive the egos of today,” Richie says. “Cameras are running, and all the mistakes are being recorded. How many release forms do you think you could actually get approved?”

He questions the modern audience too — its propensity toward the knee-jerk suspicion we saw early in the COVID-19 pandemic when a bunch of pampered celebrities were thoroughly roasted online for recording a version of John Lennon’s “Imagine.”

“We got our fair share of opinions back then,” he says. “‘Why are you asking us for money? You got all these rich-ass artists — give a million dollars apiece and leave us alone.’ But it’s gotten to the point now where you can’t sincerely say you want to help this group without getting some form of negativity. Is it really worth the hassle?

“People tell me, ‘Lionel, we need another one of those songs,’” he says with a weary chuckle. “And I just say, ‘Play “We Are the World” again.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.