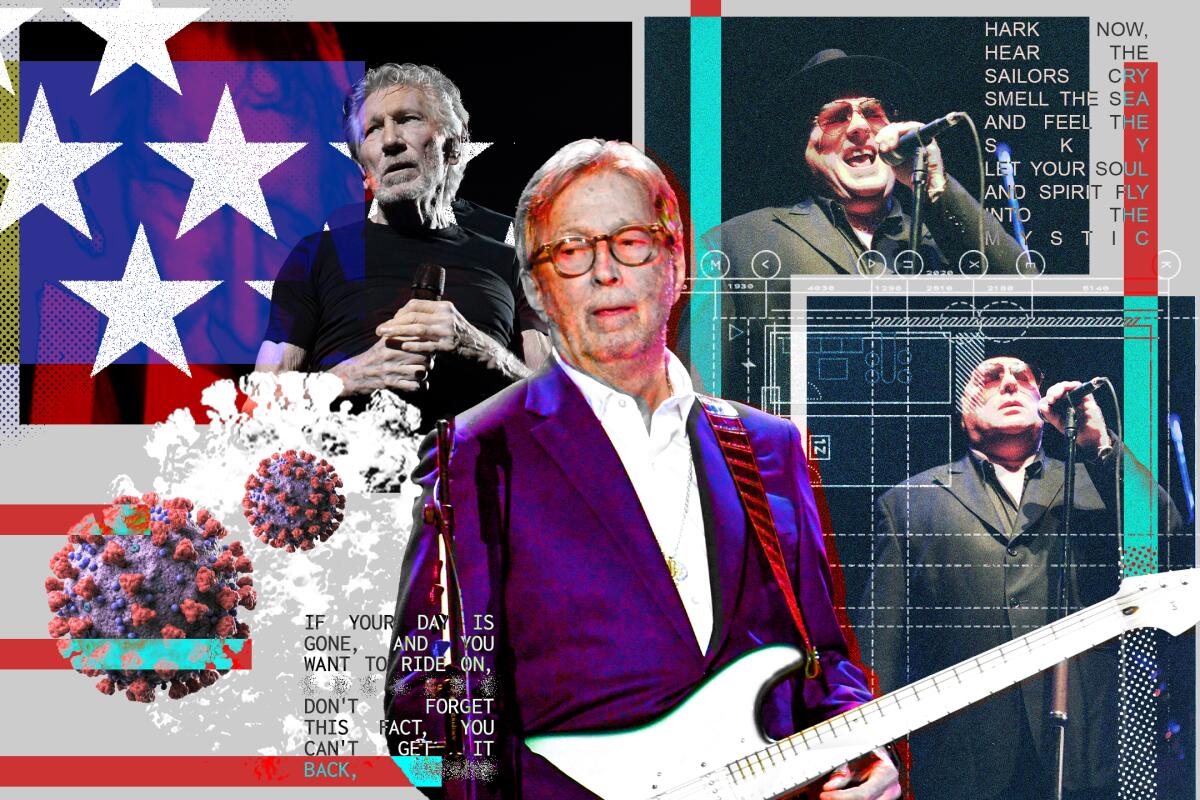

The unmasking of the narcissistic, conspiracy-spreading baby-boomer rock star

- Share via

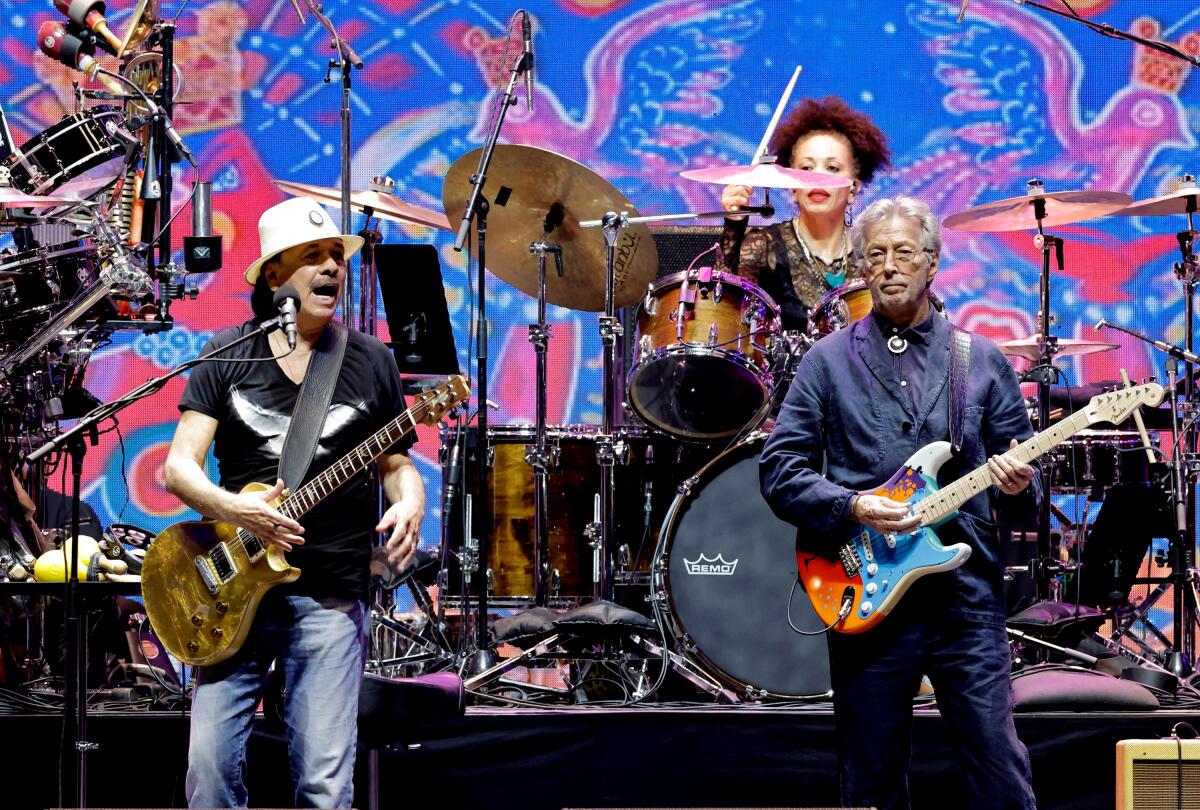

Over two nights in late September, Eric Clapton used his music-industry connections and his decades of classic-rock hits to draw thousands of fans to Crypto.com Arena in downtown Los Angeles.

The occasion was the Crossroads Guitar Festival: a once-every-few-years event for which the English singer and guitarist convenes an all-star cast of players — this one included Stevie Wonder, John Mayer, Sheryl Crow, H.E.R. and ZZ Top, among dozens of others — to raise money for the Crossroads drug treatment center Clapton founded a quarter-century ago on the Caribbean island of Antigua.

For lovers of 1960s rock, the show’s high point may have been back-to-back appearances by Roger McGuinn, with whom Clapton performed the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High,” and Stephen Stills, who joined Clapton for a rendition of Buffalo Springfield’s “Bluebird” — a trio of Rock & Roll Hall of Famers reviving a couple of the tunes that helped define the baby boomer generation.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Yet the Crossroads festival came just days after Clapton’s appearance at a smaller, very different benefit in seeming conflict with the progressive ideals many of those boomers famously embodied. On Sept. 18, Clapton, 78, headlined a fundraiser for Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the now-independent presidential candidate known for spouting anti-vaccine conspiracy theories — among other things, he’s suggested that vaccines cause autism and that the COVID-19 virus was designed not to infect Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese people — and for his coziness with conservative political figures such as Elon Musk, Jordan Peterson and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis; the event, held at a private estate in Brentwood, raised $2.2 million, according to Kennedy’s campaign.

“I am deeply grateful to Eric Clapton for bringing his musical artistry and rebellious spirit to my gathering in Los Angeles last night,” Kennedy said in a statement issued the next day. He added: “Eric sings from the depths of the human condition. If he sees in me the possibility of bringing unity to our country, it is only possible because artists like him invoke a buried faith in the limitless power of human beings to overcome any obstacle.”

John Lennon’s late-’70s song ‘Now and Then,’ now featuring all four Beatles, serves as a fitting conclusion, conveying what the band both achieved and lost.

That could be it. Or it could be that in Kennedy, the wayward inheritor of the Democratic Party’s most recognizable brand name, Clapton sees something of a kindred soul: Once regarded as part of the liberation-minded hippie movement (even if signs of dissent were clear early on), Clapton has veered conspicuously rightward in recent years, especially as pertains to COVID.

And he’s not the only one. In 2020, Clapton and the legendary Northern Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison teamed for “Stand and Deliver,” a shaggy blues song protesting pandemic lockdowns in which they ask the listener, “Do you wanna be a free man / Or do you wanna be a slave?” Months later, Morrison, now 78, released a 28-track double album full of rants about supposed welfare abuse and government mind control; one cut, “They Own the Media,” flirts with an established antisemitic trope.

Pink Floyd co-founder Roger Waters, 80, has been accused of making antisemitic remarks and has been criticized for saying that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine “was not unprovoked.” Groundbreaking guitarist and bandleader Carlos Santana, 76, shared his thoughts on the transgender community during a recent concert, telling an audience that “a woman is a woman and a man is a man — that’s it.”

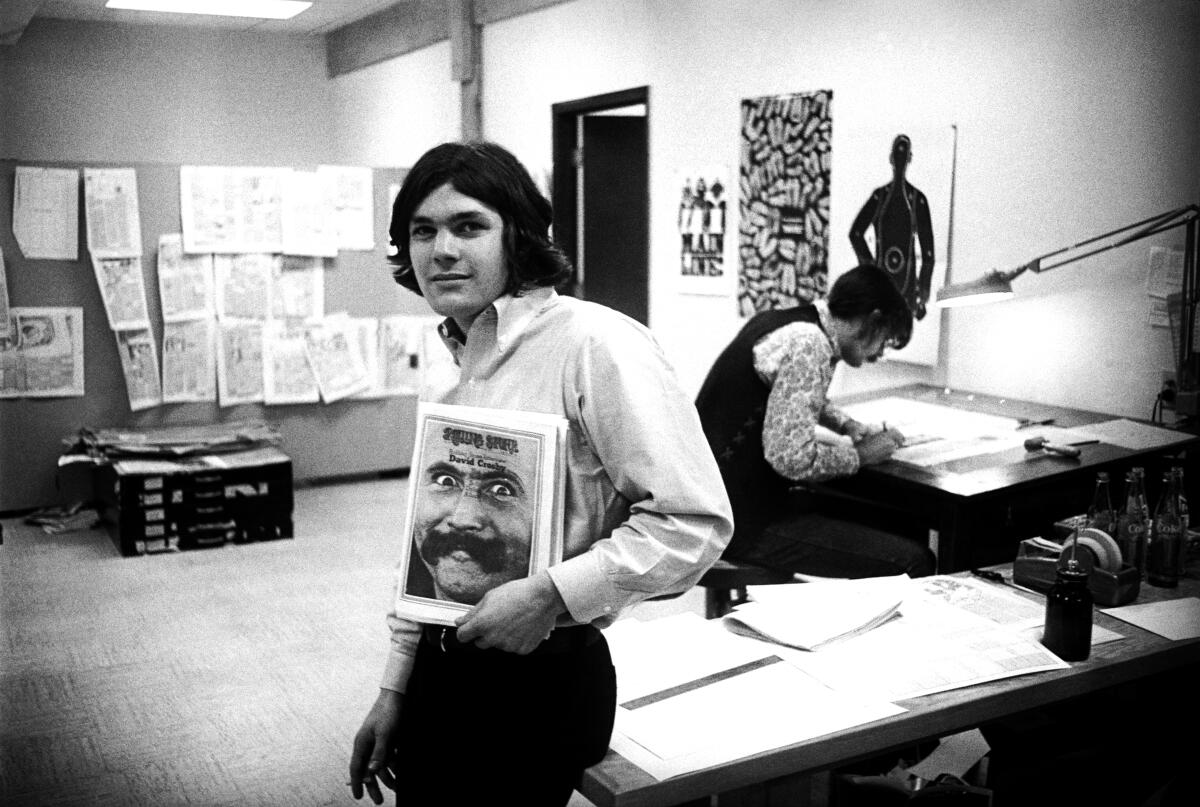

And then there’s the case of Jann Wenner, the 77-year-old Rolling Stone magazine co-founder who made headlines of his own in September when he told the New York Times that the reason his new book of interviews with musicians features only white men is because women and people of color weren’t sufficiently “articulate” or “intellectual” to merit inclusion.

On Friday night, the Rock Hall, which Wenner helped start in the mid-1980s, will induct its latest class of members, including Willie Nelson, Kate Bush and Missy Elliott, in a ceremony at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center. Yet Wenner is unlikely to be there: One day after the New York Times published its interview with the media mogul — in which he wondered, “What didn’t the rock ’n’ roll generation do?” — the board of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Foundation ousted Wenner in a vote that reportedly took just 20 minutes to complete. Wenner promptly apologized for his “comments that diminished the contributions, genius and impact of Black and women artists.” But Rolling Stone, which his son Gus now oversees, more or less disassociated itself from the founder and went on to publish a series of hand-wringing mea culpas in which editors laid out the magazine’s evolution since Wenner’s days.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Each of these examples differs in its particulars — and stands in stark contrast to the likes of Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, neither of whom has put their music back on Spotify after pulling it last year to protest the platform’s star podcaster, Joe Rogan, spreading vaccine misinformation. But together they raise the question of whether members of a generation that “made striking changes socially and morally and artistically,” as Wenner proudly described the boomers even as he undercut their legacy, have betrayed the implicit promise of the ’60s counterculture. And if they have, should we be surprised?

“Look, many people get more conservative as they get older,” said Douglas Brinkley, the prolific author and Rice University history professor. “And millions have fallen prey to conspiracy theories and misinformation. Just because you wrote ‘Astral Weeks,’” he added of Morrison’s classic 1968 LP, “that doesn’t mean you’re immune from bad science.”

Indeed, though Clapton has been inspiring outrage since at least 1976, when he went on a notorious anti-immigrant tirade onstage in Birmingham, England, the pandemic appears to have been a radicalizing event for him and for Morrison. The latter has framed his response to COVID and various corresponding public health measures as a matter of personal liberty — of freedoms trampled on by “Imperial College scientists making up crooked facts,” as he sang in 2020’s oddly jaunty “No More Lockdown.”

“We think of rock ’n’ roll stars as traveling around the world in a caravan, and here somebody was telling them they have to put a brake on what they do,” Brinkley said — one way to describe the lucrative touring business that legacy acts have wholeheartedly embraced as ticket prices soar and their own record sales decline. “A kind of selfishness ensues.”

Clapton, meanwhile, has focused on vaccines and what he views as their dangerous side effects, which he says he experienced firsthand after receiving two AstraZeneca shots. In 2021, he was photographed backstage at a concert in Austin with Texas’ strongly conservative governor, Greg Abbott, who’s signed legislation prohibiting vaccine mandates and who passed one of the country’s most restrictive abortion laws. (Clapton’s business manager told the Washington Post that the photo with Abbott “should not be interpreted as him supporting a ban on abortion,” as the Post put it.)

However shaped the guitarist’s stance was by his personal medical history, it’s not hard to detect a political dimension to Clapton’s thinking.

“The backlash to COVID presented an anti-establishment sensibility among people who weren’t politically right, who weren’t Donald Trump supporters, but who were able to use that to tap into the same sentiment that Trump always got to,” said Philip Bump, author of “The Aftermath: The Last Days of the Baby Boom and the Future of Power in America.” Added Bump: “You weren’t aligning with Trump, necessarily, but you were able to express this frustration you had about the changing world around you and the ways in which you feel imposed upon.”

As Frankie Valli prepares a don’t-call-it-a-farewell tour, the music of the legendary Four Seasons singer continues to find new audiences.

That perceived imposition is the thing that seems to unite these men, whose birth years, it’s worth noting, put them in the same generational category as Trump, even if the former president never had a countercultural impulse to speak of. After all, COVID was just one front of a larger generational war that’s pitted boomers against millennials and Gen Z — remember “OK boomer?” — on issues of gender identity, climate change and financial inequality. As Bump pointed out, the economic and technological gains of the postwar era combined to “give boomers a sense that everything was oriented around them” — a sense of blinkered self-importance only bolstered by global rock stardom for those who achieved it (or, in Wenner’s case, something adjacent to it).

“What they feel is that they’ve earned the right to speak their mind,” Brinkley said, “and that they’re not beholden to these shifting cultural norms.”

Are they, though? One seasoned music-industry insider who spoke on condition of anonymity said that if 2016’s boomer-centric Desert Trip festival were held today, they doubted that Waters — an unapologetic critic of Israel known for wearing Nazi-style costumes that he says are “quite clearly a statement in opposition to fascism, injustice, and bigotry in all its forms” — would be booked as he was seven years ago.

Yet fans at the Crossroads festival and at a Morrison gig at the Greek Theatre in September — a self-selected sample, of course — seemed largely untroubled by the musicians’ more controversial pronouncements.

Jack Freimann, who’s 62 and said he’s seen Morrison at least a dozen times since the ’80s, was sympathetic to the singer’s complaint that COVID lockdowns were keeping him from doing his job. “He’s always been a working-class guy, so I think his take wasn’t so much from an ideological standpoint,” Freimann said. “Little more practical.”

Aubrey Williams, 37, had traveled to L.A. for Crossroads with her husband, Matt, from their home in Charleston, S.C., and said she found it easy to separate the art from the artist. “They’re not shaping policy,” she said of Clapton and the rest. “At the end of the day, it’s music, and that’s what matters.”

A former major-label president offered a variation on that view, saying that these graying icons haven’t seen substantial damage to their touring businesses because few still regard them as anything like the thought leaders they once were.

“These days they’re just peddling nostalgia,” this person said, “along with the crazy stuff.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.