- Share via

The first thing I did upon arriving at John Fogerty’s home was promptly get lost. The ranch-style estate in Thousand Oaks where the Creedence Clearwater Revival singer-songwriter lives is large enough for visitors to inadvertently show up on the wrong side — a mistake I realized I made just as a large dog began barking urgently at me. But this was no guard dog, and Creedence, as she’s named, shifted promptly to tail wagging. She was a friendly golden retriever, still damp from her recent dip in the sprawling pool I would soon see in the backyard.

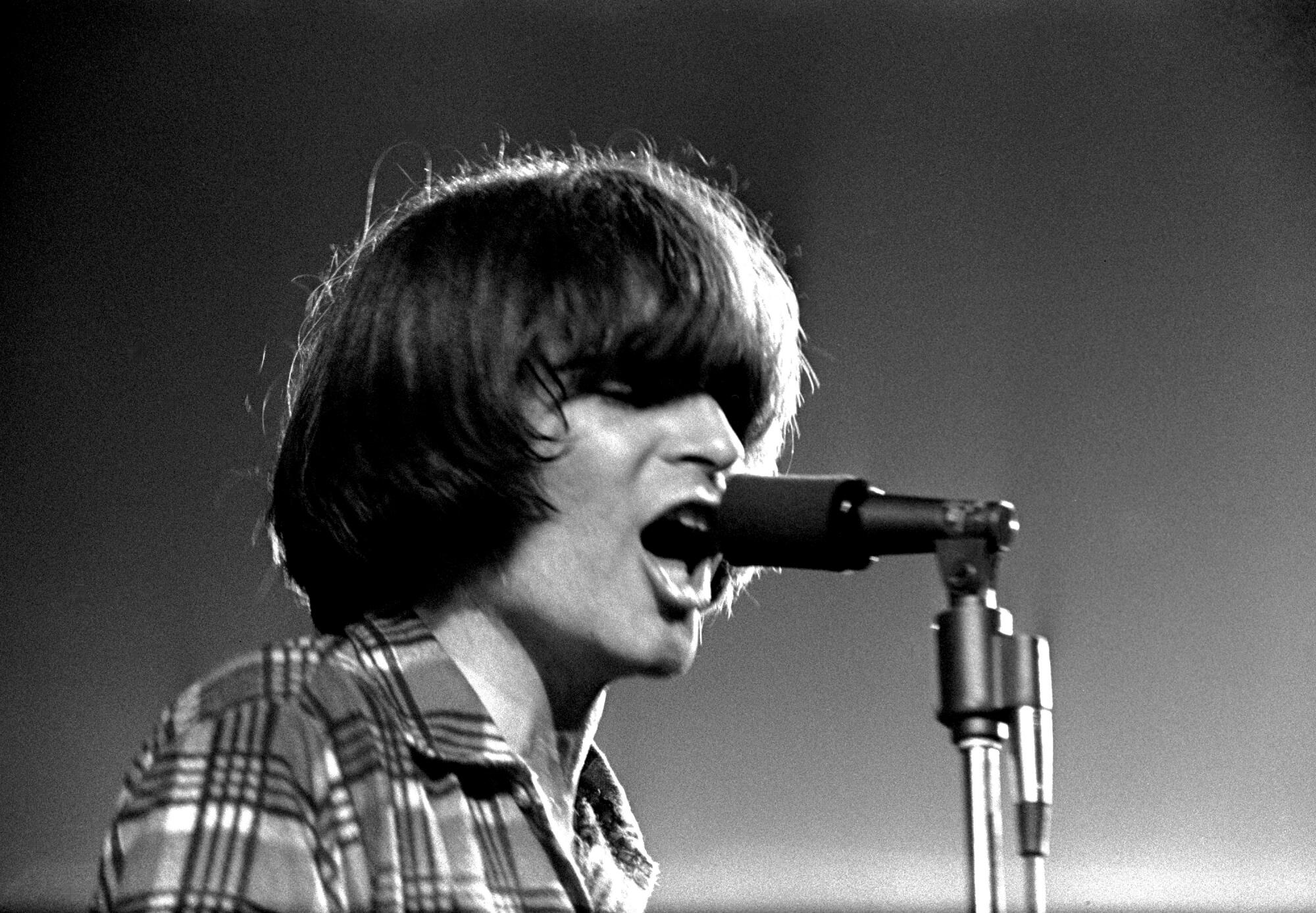

Meeting Creedence — whom everyone calls Creedy — is not a bad proxy for what it’s like to meet Fogerty himself. There is, after all, a lot of barking to consider in his past: fiery public battles with his CCR bandmates — brother Tom Fogerty, Stu Cook and Doug Clifford — as well as infamous legal sagas that have found him serving as both plaintiff and defendant. But when he sits down to talk, outfitted in a blue plaid shirt (custom made) and his trademark bandanna tied around his neck, he’s warm and casual, emitting a howdy-doody charm that belies his intense reputation.

“True, true, true,” Fogerty, 78, said, when I mentioned that even naming a dog “Creedence” doesn’t seem like something he would have done in his surlier years. For decades, Fogerty was so distraught over his experience with CCR’s label, Fantasy Records, that he refused to perform any of the songs they had control over. “That thing was signed in January of ’68,” he said, referring to Creedence’s contract, which handed Fantasy all copyrights, while also requiring the band to write 180 original songs. “And basically, we were doomed.”

Creedence’s contract has lingered for half a century as a cautionary tale in the music business, but in January, a new deal was struck that handed Fogerty back the global control of his CCR catalog for the first time — a disarmingly positive, straightforward ending to a toxic, labyrinthine story. “A lot of rain has fallen on my raincoat,” Fogerty said. “And at some point there’s a certain humility about anything going right. I received this that way. I’m just very happy that it has happened now.”

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

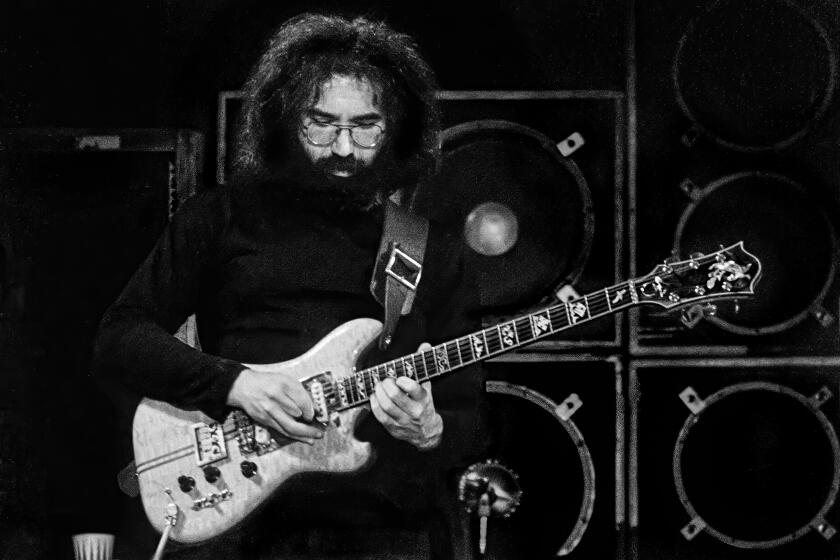

Friends from Portola Junior High School in El Cerrito, Calif., Creedence Clearwater Revival released its self-titled debut album in 1968, at a time when psychedelia was the lingua franca of the rock underground. Creedence was instead defiantly roots-rock- and blues-oriented, owing far more to Elvis Presley and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins than Bay Area contemporaries like the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. Partnered with Fogerty’s brilliantly economical songwriting — simple, anachronistic fables about boats, porches and storms; sly, working-class anthems about inequity, strife and consumerism — the combination made for a rarity then and now in popular music: a band that crossed the aisle, for which many people and demographics agreed on.

Creedence had nine Top 10 songs and two No. 1 albums in the span of just a couple of years, giving them a sleeper case for the title of biggest American band in the late ’60s/early ’70s. “They literally had to expand airports to accommodate them,” John Lingan, author of the 2022 CCR biography “A Song for Everyone,” told me, in reference to the accommodations made for the band’s private jet on a 1970 European tour. “They were just a massive, massive group.” Yet the relationship between Creedence and Fantasy was so dysfunctional that, in 1980, Fogerty relinquished his royalties in order to be freed from the contract. (The royalties were restored in 2004, after Fantasy was sold to Concord Music Group.) Fogerty’s ranch may be palatial, but in some sense, it should probably be bigger.

It took no less than the prodding of Bob Dylan at a show in 1987 for Fogerty to even begin playing Creedence songs again — Dylan told Fogerty, “If you don’t do ‘Proud Mary,’ everybody’s gonna think it’s a Tina Turner song” — which marked the beginning of a willingness to embrace his most beloved songs. And after the recent victory of buying back a majority stake of his CCR publishing rights from Concord, he is finally in a decidedly peaceful era.

Fogerty is currently wrapping up what’s been billed as the Celebration Tour, joyously playing CCR classics like “Who’ll Stop the Rain” and “Down on the Corner” — songs he first toured around the world in his early 20s, utilizing one of the greatest howls in rock history. But in this iteration, he plays those songs in a band that includes two of his sons, Shane and Tyler Fogerty, who help their father reach the notes that are no longer quite as easy for him to get to these days. Fifty-plus years since Tom quit the group, leading to the quick demise of Creedence, John Fogerty is once again in a family band.

“I wasn’t trying to make little prodigies,” John said, sitting in his home recording studio, flanked by Shane and Tyler, who both bear a scruffy, retro resemblance to their father. “In some ways, because of my past — there was some unpleasantness to do with showbiz, and I wouldn’t wish that on my best friend,” he said of any apprehension for his children to follow in his footsteps. “But there it was. It evolved kind of naturally.”

Shane, 32, and Tyler, 31, didn’t grow up with the instinct to follow their father into the music industry. But the bug bit them in due time — John recalls a preteen Shane asking how to play AC/DC’s “Back in Black” — and they both ended up in a “School of Rock”–style band camp, where they were eventually playing CCR songs. “I think our first performance we did was ‘Proud Mary’ and maybe ‘Bad Moon Rising,’” Shane remembered. Tyler cut in, grinning: “That was our mom,” he said. “She made us do that.”

Jacob Rock has profound non-oral autism. But thanks to text-to-voice software and a music-loving dad, Rock transposed the sounds in his head to the concert stage.

Julie Fogerty, their mom, is John’s second wife — and also his manager. She’s been reluctant to embrace the latter title at times, but when the pandemic hit, she took charge, wrangling the Fogerty clan — Shane, Tyler and Kelsy, the youngest child of John and Julie — for weekly performance videos. The releases were sweet little escapes during the pre-vaccine era, as the family would play in idyllic backyard settings appropriate for songs that have become a permanent fixture in the American songbook, passed down from generation to generation.

And so when this current tour kicked off, John and Julie decided not to mess with the formula. Shane and Tyler packed up their own plaid shirts, and enlisted members of their band, the psych-rock sextet Hearty Har, to support John as well. (Kelsy is now away at college.)

Spending time with this wiser, softer version of John Fogerty — certainly more Moses than Cain at this point — it’s difficult to see him as the same person who traded barb after barb with his bandmates; who once broke his hand punching a chair in frustration during a trial in which Fantasy accused him of plagiarizing one of his own Creedence songs. (Fogerty won that case.) “I think he mellowed out a little bit when we were growing up,” said Tyler, during a separate interview with Shane away from their dad. “He has a temper sometimes. But usually his way of dealing with stuff is different than most people, because he lives in his own little fantasyland where he doesn’t have to deal with many realities that a lot of people do.”

John can nonetheless get amped up rather quickly. In conversation, he’ll bring up politics (“anything to do with Donald Trump still gets me [on] the Richter scale”), and at one point he went out of his way to remind me that he was writing about gun control as early as 1970, with “Run Through the Jungle,” which, despite its use in Vietnam movies, is not actually about Vietnam. “Every year it just got worse and worse,” he said, referring to the mass shootings that originally inspired the song. “And now it’s daily.”

But the John Fogerty of 2023 is in many ways an ordinary baby boomer father. He spends his days as a frustrated Oakland A’s fan (Fogerty was not, in fact, born on the bayou, but instead in El Cerrito, a Bay Area suburb); he amuses his kids with a preoccupation with the house thermostat; he sneaks fast food when no one’s looking. (Kelsy, a vegan, convinced her dad to stop going to Taco Bell, an establishment he’d been patronizing since the 1960s.)

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

There are some remaining holes in this wholesome chapter, however. When I asked John about whether he was also close to his other three children, from his first marriage to Martha Paiz, he said, “Not like it should be, no,” growing somber and serious. “Haven’t seen them very much in the last many years. I wish I had seen them more.” He said he shared blame for that distance with his ex-wife: “I try to say it with all dignity and diplomacy: We didn’t end up supporting each other.”

Shane called the matter of John’s other family and the family of their uncle Tom, who died in 1990, a “weird unresolved thing.” “We don’t have a say in how much we see his old family and that other side,” he said. “Our dad, he doesn’t talk about it. … I think it’s painful for him. And I don’t know if he knows what the answer is. If there is a way to do it without somebody getting hurt.”

A new lineup. A new label. A new studio: Following the death of Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan, Jerry Garcia and the Dead reinvented themselves on ‘Wake of the Flood.’

Given their bloodline, it’s worth wondering how Shane and Tyler get along — but they say they’re nothing like John and Tom. Tyler noted that they’re not competitive about who plays what in Hearty Har, and that he prefers “to be surrounded by people with differing ideas.” The bigger issue is convincing people that they’re not like CCR — in dispelling the expectations of being the sons of John Fogerty. “Sometimes it’s the best thing,” said Shane, “and then other times it’s the worst curse because you’re always going to be compared to what came before you, what your dad did, what he’s still doing. And I think that’s OK. But it’s also, ‘Now that we got that out of the way, we’re totally doing something our own here.’”

Even with the tremendous resources they have, it hasn’t been easy getting a foothold with Hearty Har, who have been opening shows on the Celebration Tour. “It’s hard when you know it’s actually good,” Tyler said, “and then you’re constantly running uphill just to keep it afloat.”

Their dad, who’s monitored the ebbs and flows of the music industry since the 1950s, is likewise bewildered by its current state. “I realize it’s a really tough time to try and break a band,” he said. “Because records don’t sell — they stream. And you can’t live off of that.” (Creedence, anyway, has transitioned tremendously well into the streaming era; on Spotify, they have a higher number of monthly listeners than the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin.)

Not that the industry has ever been particularly easy for Fogerty to navigate. “It was something that was really hurtful and painful to John, to know that his music wasn’t his own,” Julie told me. That hurt colored the rest of his career, which consisted of a sporadic and uneven solo output; two charming records of his that were recently reissued, for instance — 1973’s “The Blue Ridge Rangers” and 1975’s “John Fogerty” — feature him playing every instrument, a rebuttal to the idea that he needed anyone’s help. (To this day, Fogerty is on poor terms with CCR’s Cook and Clifford.) Until Julie came into his life, in the late ’80s, John was a self-admitted mess, drinking too much, spending more time camping in the woods than working on music.

“The right word isn’t stubborn — John can be principled,” said Irving Azoff, the mega-manager and industry giant who at one time worked with Fogerty, and helped broker the new Creedence deal as a favor to an old friend. (Azoff was brought in to help by Julie after an initial failed attempt to strike a deal with Concord — only the latest of several in-earnest negotiations over the decades for Fogerty to purchase a stake in his catalog.) “People misunderstood those principles during the old years. … But God bless him for sticking to his principles — and he felt he had to, to have any self worth. I’ve never seen an artist happier over the conclusion of a deal than when this deal closed.”

Susan Genco, co-president of Azoff Co., worked closely with Fogerty and Concord to negotiate the terms, the financial specifics of which have not been made public, but have been described as beneficial for both parties, while granting Fogerty control. “I’m glad that Concord got it,” she said, describing a scenario in which the record company became increasingly willing to find a deal based on the idea that it was the right thing to do. “We only have jobs because of the artists. And this [initial CCR contract] really impacted his creative ability. Now you can see the difference on stage, like the burden is lifted.”

Fogerty’s publishing coup comes at a strange time, given the trend of other powerhouse artists, like Bruce Springsteen and Bob Dylan, selling their catalogs. And given that Azoff owns a rights management company, Iconic Artists Group, which has purchased stakes in catalogs from artists like the Beach Boys and Linda Ronstadt, it’s reasonable to wonder if the Creedence publishing might be on the move again sometime in the future. Azoff said there was no such intent behind his help, and Fogerty noted he’s not at a point where he would be interested in selling. Still, Fogerty added, he “might get there.”

“But the joy of getting to sing ‘Bad Moon Rising,’ knowing that it finally came back,” Fogerty said, “and I’m standing here with my kids in a band, singing our hearts out. ... Now this is the part that’s pretty corny. It’s just the greatest. I’m quite sure a 22-year-old John Fogerty was...” Here, Fogerty raised his hands and growled, growled like he used to in 1970, with his mop-top, leather pants and sizable chip on his shoulder. Then he settled back in his chair. “But you get older and you just appreciate it. In other words, it’s not corny to you. It’s just real life.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.