From East L.A., the Stains’ Robert Becerra was a punk-rock legend, to those in the know

- Share via

When 15-year-old Jack Rivera told his friends in Boyle Heights he was going to be the new drummer of the fledgling punk band the Stains, some people in the neighborhood warned him: “Be careful. Those guys like to party.”

It was 1981 and Rivera, who went by Gilbert Berumen before he changed his name, was still a sophomore at Theodore Roosevelt High School. After school he’d go to band rehearsal at Robert Becerra’s house on Third Avenue in Boyle Heights, where the guitar player lived with his mother. By the time Rivera arrived, Becerra was barely getting started with his day and whomever he’d been partying with the night before was just waking up.

That’s how Rivera met fellow punk-rock musicians like Scott Franklin of the Mau Maus, Chett Lehrer of Wasted Youth and Rudy Navarro, another teenager from Temple City whom Becerra had big plans for.

“He’s our new singer,” Rivera recalled Becerra telling him.

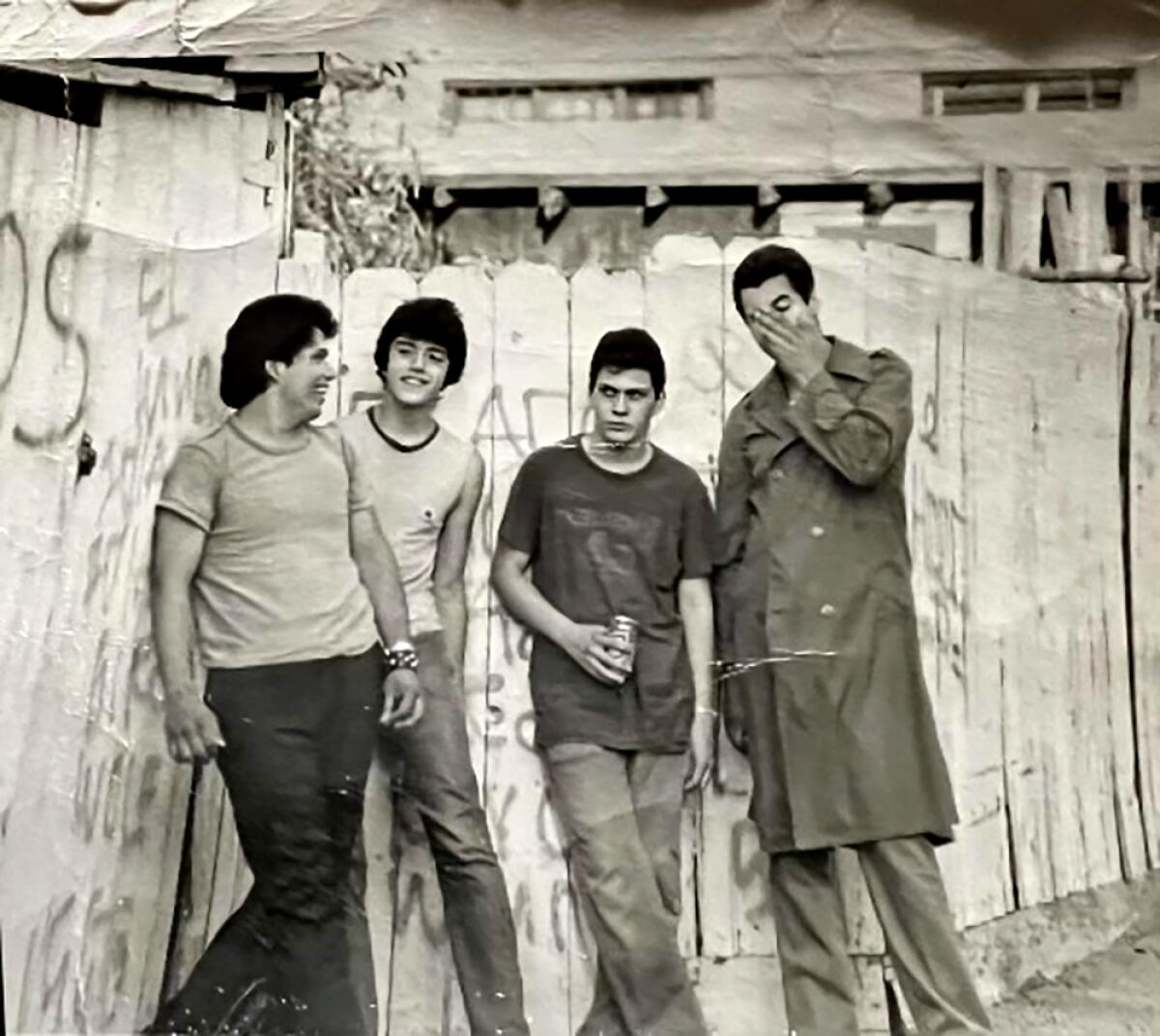

Becerra, a longtime if little-known fixture in L.A.’s punk rock scene, died of liver cancer on Sept. 1 at age 64 at White Memorial Hospital in Boyle Heights. He was born on Dec. 17, 1958, in Boyle Heights and raised by his mother, Carmen Rodriguez, who supported her three sons — Sal, Ollie and Robert — as the head nurse in a nursing home. In the ’70s, when many of Becerra’s childhood friends turned to drug-dealing and gangs, he started the Stains with singer Jerry “Atric” Castellanos, bassist Jesse “Fixx” Amezquita and drummer Tony Romero. (Rivera replaced Romero in 1980 and Rudy Navarro replaced Castellanos in 1981).

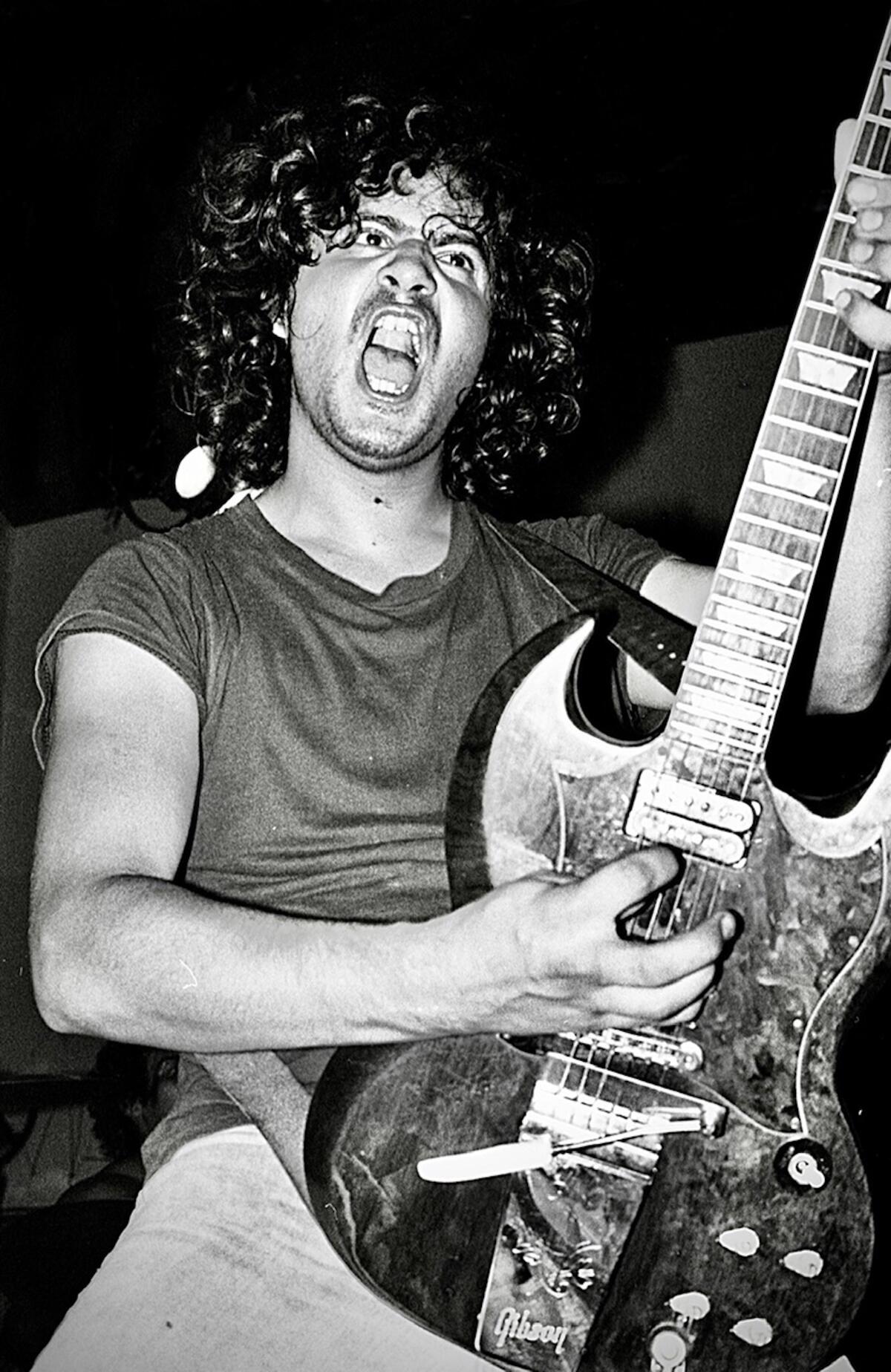

The Stains blended Becerra’s blistering guitar riffs with Amezquita’s lyrics about living at the margins of society to create a sound that combined the urgency of punk with the precision of metal — years before newer subgenres like thrash or speed metal became prevalent. Although the band members were all Mexican-Americans and were among the first — if not the first — punk rockers from the Eastside, they saw themselves as part of the larger community of first-wave Hollywood punks that included X, the Plugz and the Gears.

The parties at Becerra’s house would start after the punk-rock shows in Hollywood or Chinatown and go all night. They weren’t strictly parties but epic jam sessions that would be attended by the likes of Greg Ginn and Chuck Dukowski of Black Flag, John Doe and Exene Cervenka of X or whoever else wanted to come over and play.

Becerra would kick off the evening by careening through a handful of Ramones songs — he’d attended all five nights of the band’s run at the Whisky a Go Go in 1977— and then launch into his favorite tunes by ‘70s rockers Mott the Hoople and Hawkwind.

“Robert could listen to a record and play it back to you note for note,” Rivera recalled.

“Robert was a wild man and pushed his art to the limit,” says X’s Doe. “We had no idea that his blend of metal and punk guitar playing was so far ahead of its time. He was a pioneer.”

What set the Stains apart from their peers, according to punk-rock historian Jimmy Alvarado, was Becerra’s astonishing talent. The self-taught musician could play his instrument in a wide range of styles.

“He was heavy into Deep Purple and Black Sabbath and bands like that,” Alvarado said, “but he’d also been influenced by Andrés Segovia and other classical guitarists. That manifests itself in the weird way that he approached the guitar and made what he did sound even more chaotic and crazy.”

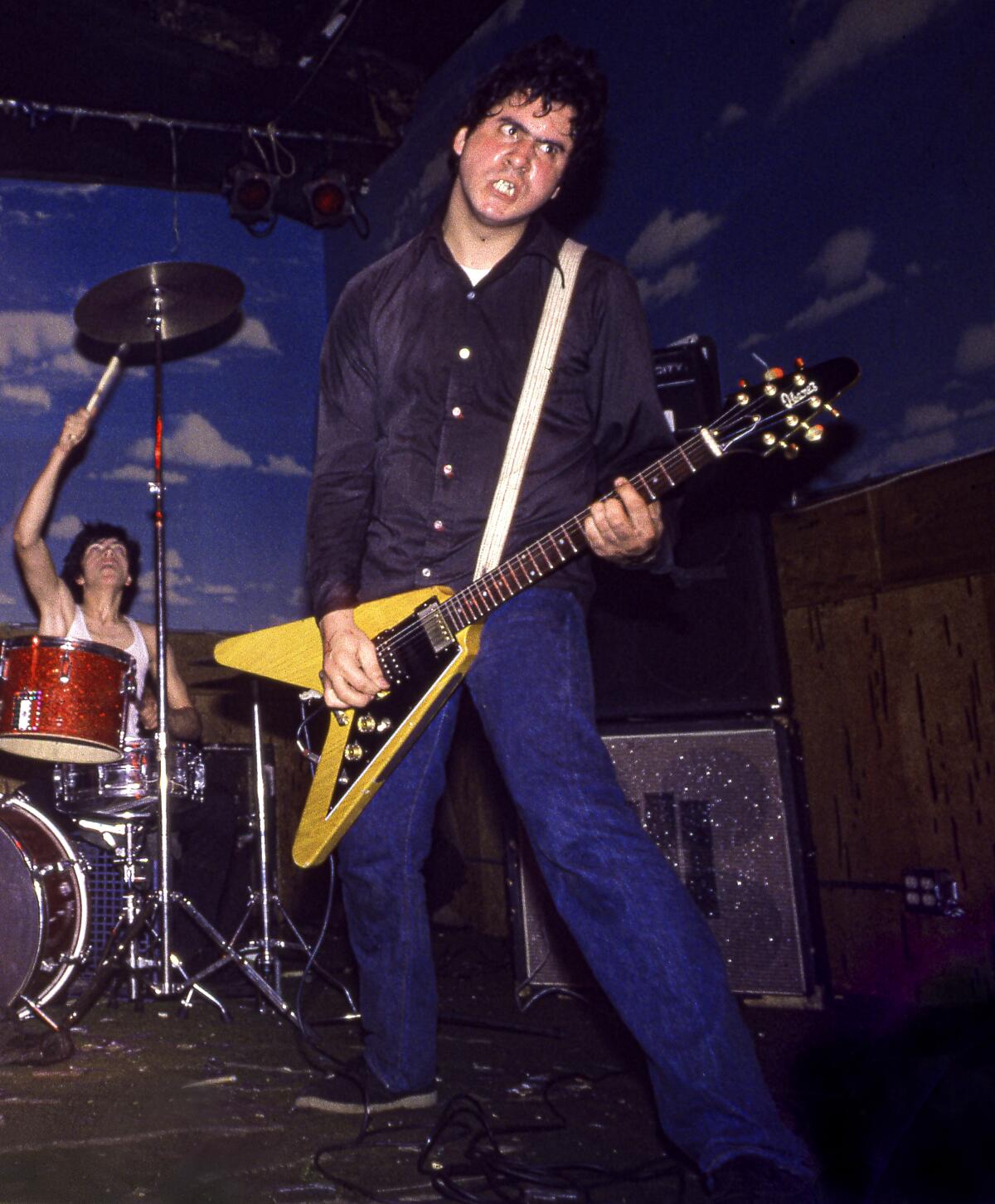

At a time when punk rockers frowned on guitar solos and flashy playing, Becerra embraced both, usually while stomping around the stage, leering at the audience and playing harder and faster than many of the hardcore bands that were taking over the L.A. punk scene.

“He was a genius at improvisation,” said Michael Vallejo, a guitar player from Pico and co-founder of the hardcore band Circle One. “He never played the same guitar solo twice.”

One band that was particularly taken with Becerra’s style of play was Black Flag.

“When we used to play shows they would come over and watch,” Becerra said of Black Flag in an interview in October 2021. “Greg Ginn and Chuck [Dukowski] and all those guys would come by and see us.”

“Black Flag loved the Stains,” confirmed Dez Cadena, who played with Flag, first as a vocalist and then as guitar player, from 1981 to 1983.

Eventually, SST Records, which Ginn founded, approached the Stains about recording an album. In 1981 the band made its way to Hermosa Beach to record its 11-song self-titled debut in the same studio where Black Flag, the Minutemen and Saccharine Trust recorded early material for the label.

The album was recorded after-hours to take advantage of cheaper rates and produced by the late, legendary producer Spot. Becerra’s idiosyncratic style is apparent from the opening notes of the first track, “Sick and Crazy.” A squall of noise disintegrates into a martial riff that would send fans into a frenzy.

The Stains’ reputation for playing intense shows followed them all the way to Texas, where a local band calling itself the Stains decided to change its name to MDC prior to playing with L.A.’s Stains at the Cuckoo’s Nest in Costa Mesa.

However, Navarro left the band not long after recording the album, leaving the Stains without a singer. When he wasn’t on the road with Black Flag, Cadena would spend weekends at Becerra’s house. After Navarro left the band, Cadena entertained thoughts of joining the Stains but was talked out of it by Spot.

SST, which was engaged in an expensive lawsuit with Unicorn Records, had a backlog of unreleased records and was focused on issuing albums by active bands that could be counted on to tour. As a result, the Stains’ record wasn’t released until 1983. By then they had broken up, and Becerra was focused on a new heavy metal project called Nightmare. Aside from a handful of demos and practice tapes, Nightmare never recorded an album.

“They would go inactive for a while or someone would leave,” Cadena said of the Stains. “I wish they had stayed together so they could tour across the country a couple of times, put out a few more records, because Robert’s guitar playing and their music is just as important to me as the Germs album.”

Throughout the ’80s, Becerra worked a series of odd jobs that included brief stints at a gas station, a tattoo parlor and even as a janitor at Breed Street Elementary in Boyle Heights. Becerra married Jenny Cohl in 1996 and they lived in Northern California and then Detroit to help care for Cohl’s mother before returning to L.A. The couple separated in 2008.

Cohl recalled that Robert would practice all day and when he fell in love with a band he would learn all their songs and play them perfectly. “He never lost his love of music,” she said.

After a handful of reunion shows at the Country Club in Reseda in 1989 and the Vex in L.A. in 2001 and 2013, the Stains faded away and their record became a collector’s item, with prices climbing as high as $1,200.

Beset by debilitating health issues, Becerra eventually stopped playing guitar. While seeking treatment for cirrhosis of the liver in 2022, he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

“He was so confident and so good,” Rivera said. “He should have been on the cover of Kerrang!”

“He was so expressive and it came from his heart,” Cohl said, “That’s why he was such a good guitar player.”

Becerra is survived by Cohl.

Jim Ruland is the author of “Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.